Portland, with a 2020 population of 652,503 within its city limits and 2,226,009 in the seven-county metropolitan area, was platted on the west bank of the Willamette River in 1845 on lands used traditionally by Multnomah Chinooks. The area received its first few dozen English-speaking settlers in 1846. Maine native Francis Pettygrove, one of its first proprietors, chose the name. During the 1850s, Portland would pass Oregon City to become the largest city in Oregon, a position it has held ever since. The metropolitan area is twenty-third in size in the United States.

During its first three decades, Portland depended on trade by water. Its first substantial growth came when the California Gold Rush created a huge market for Oregon wheat and lumber, much of it shipped from Portland by river and ocean to San Francisco. Willamette River steamboats brought farm products from the state’s agricultural heartland, while steamer links connected by portage railroads on the Columbia River allowed Portland merchants to supply miners in Idaho and Montana. The Oregon Steam Navigation Company, which had consolidated and monopolized the Columbia River trade by 1860, was the basis for several sizable fortunes.

Along the lower Willamette and Columbia Rivers, Portland outcompeted rival cities by combining astute boosterism with a well-chosen site. Sandbars made it difficult for ocean-going ships to go south beyond Portland and limited the growth of nearby Milwaukie and Oregon City. A conveniently located pass through the Tualatin Mountains (also known as the West Hills), traversed by a rudimentary plank-surfaced road after 1851, gave the city relatively easier access to the farms of Washington County than was available to St. Helens, the most likely rival to Portland in the 1850s and 1860s.

A well-established and prosperous city by the 1870s, Portland experienced a prolonged era of growth with the expansion of the regional railroad system from the 1880s to the 1910s. Completion of a transcontinental link via the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1883 was important in both symbolic and real terms, but consolidation of the Portland-centered rail network continued for another generation as large and small lines opened the western Oregon mountains and the Columbia Basin interior to logging, ranching, and agriculture. Flour mills, lumber mills, furniture factories, and shipyards lined the Willamette waterfront and major rail corridors, while lumber schooners and grain ships crowded the river.

Booming commerce meant booming neighborhoods. The first three bridges spanned the Willamette River between 1887 and 1891. Entrepreneurs used the bridges to extend electric streetcars (an innovation that dated to 1888) several miles into north, northeast, and southeast Portland. The number of eastside residents in new neighborhoods from Piedmont to Brooklyn passed the number of westside residents in 1906.

Rapid growth also attracted people from different ethnic groups to Portland. In the 1880s, the city’s large Chinese community was second in numbers only to San Francisco’s. The next decades brought immigrants from Japan and from Scandinavian, Eastern European, and Mediterranean countries. At the height of immigration in 1910, the largest contingents of foreign-born Portlanders were from the British Isles, Canada, China, Germany, and Sweden, followed by immigrants from Russia and Italy. Residents in the first decades of the twentieth century could identify South Portland as an Italian and Jewish neighborhood, Brooklyn as Italian, Sabin as German, and Slabtown as Irish and then Croatian. Scandinavians clustered in parts of Northwest and in Albina. Several blocks north of Burnside Street was Japantown, and many from Portland’s small African American community lived near Union Station for ease of access to railroad jobs.

In the first years of the twentieth century, the business and civic leadership took key steps to demonstrate the city’s maturity and to keep in step with the reforms promoted nationally during the Progressive Era. In 1903, landscape architect John C. Olmsted prepared a comprehensive park plan for the city that resonates more than a century later. He also designed the grounds for the successful Lewis and Clark Exposition in 1905. Following a similar world’s fair in St. Louis the year before, the exposition solidified Portland’s reputation as a can-do city.

Seven years later, Edward Bennett prepared a transportation and land-use plan that gave Portland a document comparable to the Plan of Chicago, which Bennett had co-authored in 1909. In 1913, Portlanders responded to vice scandals and scathing critiques of municipal inefficiency and corruption to approve the city commission form of government, then considered a forward-looking reform, by the paper-thin margin of 292 votes.

Growth slowed in the 1920s and 1930s as Portland adjusted to the increased use of automobiles and to the slowing of agricultural expansion in the Pacific Northwest. Radical intellectuals such as C.E.S. Wood, John Reed, and Louise Bryant had already departed for more compatible places. One journalist aptly characterized the political climate when he commented in 1931 that “to know what Portland would do in the press of any given circumstances, it is only necessary to know what Calvin Coolidge would do.”

World War II cracked open Portland’s insularity. Local shipyards picked up defense contracts in 1940, and industrialist Henry Kaiser arrived in the city to set up three huge shipbuilding facilities on Swan Island and at St. Johns and in Vancouver, Washington, across the Columbia River. Defense employment in the Portland-Vancouver area peaked at 140,000 workers, 92,000 of whom received paychecks from Kaiser. Together, the two cities produced more than a thousand ocean-going combat and cargo ships from 1941 through 1945.

With regional population growing by one-third from 1940 to 1943, Portland took on a boomtown atmosphere. Residents had to accommodate workers from such states as Arkansas and Oklahoma and the city’s first substantial numbers of African Americans (from 2,000 in 1940 to 15,000 in 1945). Many of the newcomers lived in the city of Vanport, built in 1942-1943 adjacent to the Columbia River, which would destroy it by flood in 1948.

Portland’s municipal institutions had difficulty keeping up with the boom and no effective strategy for continued growth after the shipyards closed. From 1913 into the 1950s, political habits, corruption, and cronyism died hard in the city. One reform mayor, Dorothy McCullough Lee (1949-1952), was elected, but many more “business as usual” mayors such George Baker (1917-1933), Earl Riley (1941-1948), and Fred Peterson (1953-1956) held that office.

In 1957, the city received abundant negative publicity when the U.S. Senate’s McClellan Committee publicized police and labor union corruption. The hearings showed the downside of the prevailing attitude that Richard Neuberger had described in 1947: “Portland’s atmosphere is one of placidity and gentle living. Its traffic pace is the slowest on the coast.” He added: “Most Portlanders…would probably say they want their city to go on being…a slow and easygoing trading center.”

Both politics and the civic tone in Portland changed markedly in the late 1960s and 1970s. An expanding electronics industry and growing universities attracted outsiders with new ideas, and the average age on Portland City Council dropped by fifteen years between 1969 and 1973. A new generation of civic activists transformed political discourse in the city. In the course of a few years, between 1968 and 1974, Portland leaders decided to remove Harbor Drive, a multi-lane expressway on the west shore of the Willamette River, in favor of what is now the expansive Tom McCall Waterfront Park; shifted money from the so-called Mount Hood Freeway through southeast neighborhoods in favor of funding the first light-rail line from downtown to nearby Gresham; created the Office of Neighborhood Associations; and completed a landmark Downtown Plan that paved the way for the Transit Mall and Pioneer Courthouse Square.

Although the new political activism focused on conserving downtown and inner neighborhoods like Northwest, Corbett-Lair Hill, Irvington, and Buckman, the strongest demographic trend was continued suburban growth. New subdivisions and communities filled in the Hillsdale-Burlingame-Raleigh Hills areas to the southwest. Eastward toward Gresham, neighborhoods were created east of 82nd Avenue, an area originally outside the city limits that would be annexed in the 1980s and 1990s. By the 1970s, the suburban frontier was advancing in Clark County (Washington), Clackamas County, and especially Washington County, where Tektronix, Intel, and small electronics companies were creating what became known as the Silicon Forest. By 2010, the suburbs of Gresham, Hillsboro, and Beaverton stood fourth, fifth, and sixth in population among Oregon cities.

The City of Portland is the center for a large metropolitan area that functions as an integrated employment and market region. The U.S. census first defined a Portland “metropolitan district” in 1920 and adopted the terminology “standard metropolitan area” in 1940, when metropolitan Portland included Multnomah, Washington, and Clackamas Counties in Oregon and Clark County in Washington. As census terminology repeatedly changed, the formally defined metropolitan area expanded to include Yamhill County in the 1980s, Columbia County in the 1990s, and Skamania County (Washington) in the twenty-first century. Several public agencies, including Metro (a popularly elected regional government), the Port of Portland, and the Tri-County Metropolitan Transportation District (TriMet) provide services for part or all of Multnomah, Washington, and Clackamas Counties.

The revival of immigration to the United States after the Immigration and Nationality Act passed in 1965 had a distinct impact on the Portland region. At a far remove from the American South and Mexico, Portland in the mid-twentieth century was one of the whitest cities in the country. That began to change most noticeably after 1990, when immigration from Latin America, Asia, the Pacific Islands, and Eastern Europe changed the racial and ethnic mix. By 2010, the U.S. census reported that 76 percent of Portland metropolitan area residents identified themselves as non-Hispanic white. Immigrant communities spread widely through the Portland region. In 2012, the Beaverton, Forest Grove, and Hillsboro school districts in Washington County and the Parkrose, David Douglas, Centennial, and Reynolds districts in eastern Multnomah County had more ethnically diverse student bodies than the Portland Public Schools did.

Portland in the early twenty-first century has multiple civic personalities. Inner neighborhoods have become increasingly hip as the region attracts substantially more than its share of college-educated people aged twenty-one to thirty-five. This facet of Portland draws on an idiosyncratic heritage in the arts represented by artists such as filmmaker Gus Van Sant and writer Ursula K. Le Guin and on quirky small businesses from Dark Horse Comics to microbreweries. In 2011, the city was skewered in the satirical television series Portlandia, which was in its fourth season in 2014.

Overlaid on hipster Portland is an earnest policy-wonk city whose citizens read books, enjoying one of the nation's most heavily patronized public libraries and largest independent bookstores, and place a high value on civic participation. These traits have repeatedly earned it “most livable city” rankings since the earliest such study in 1975. Surrounding the progressive core, however, are more typically American “silicon suburbs” and economically struggling neighborhoods of African Americans, Latinos, and others who have little reason to appreciate the humor of Portlandia. The challenge to civic leaders and citizens is to find ways to bridge rather than widen the resulting political, economic, and cultural gaps.

-

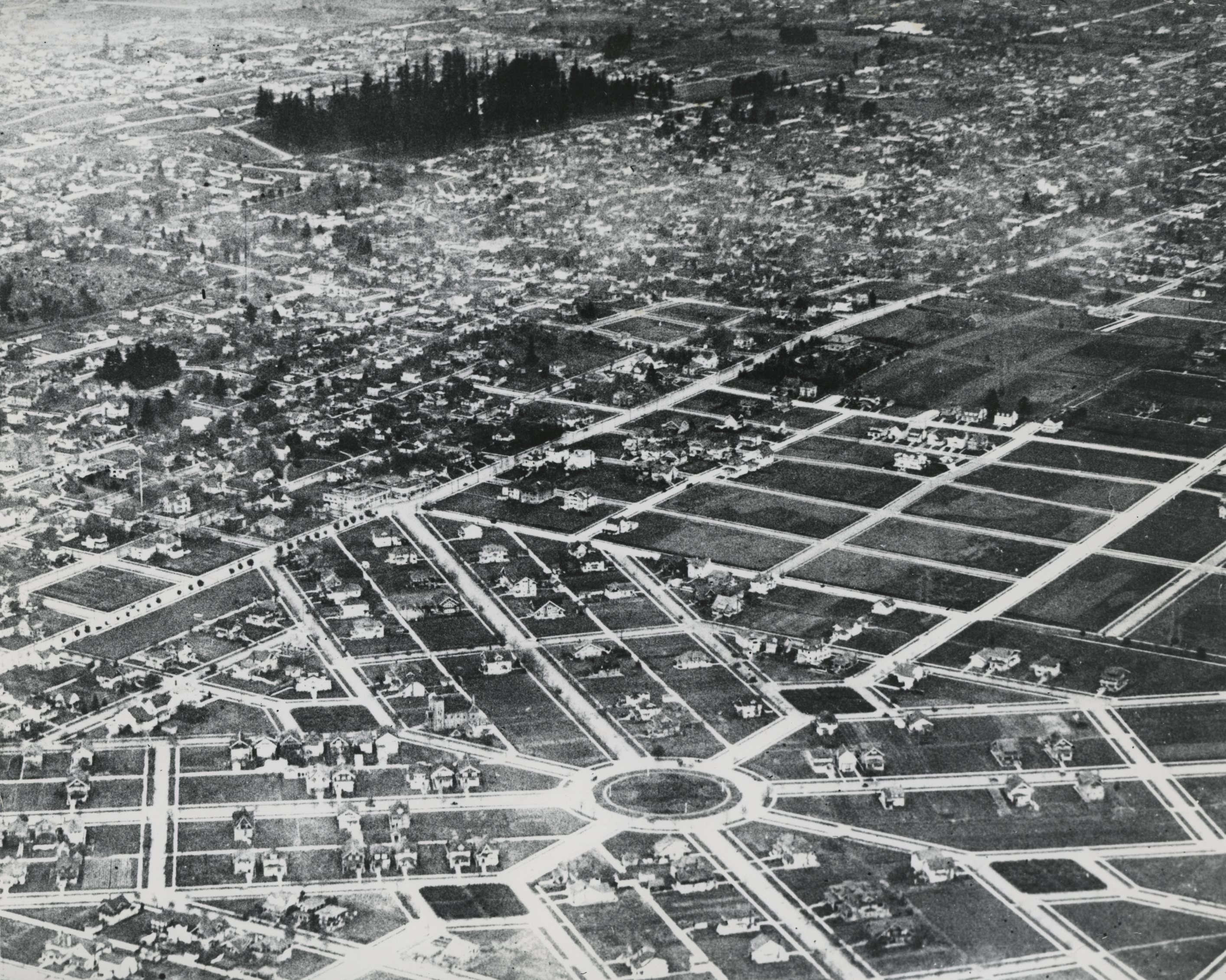

![]()

Early Portland, "Stumptown".

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, ba019143

-

![]()

Downtown Portland.

-

![]()

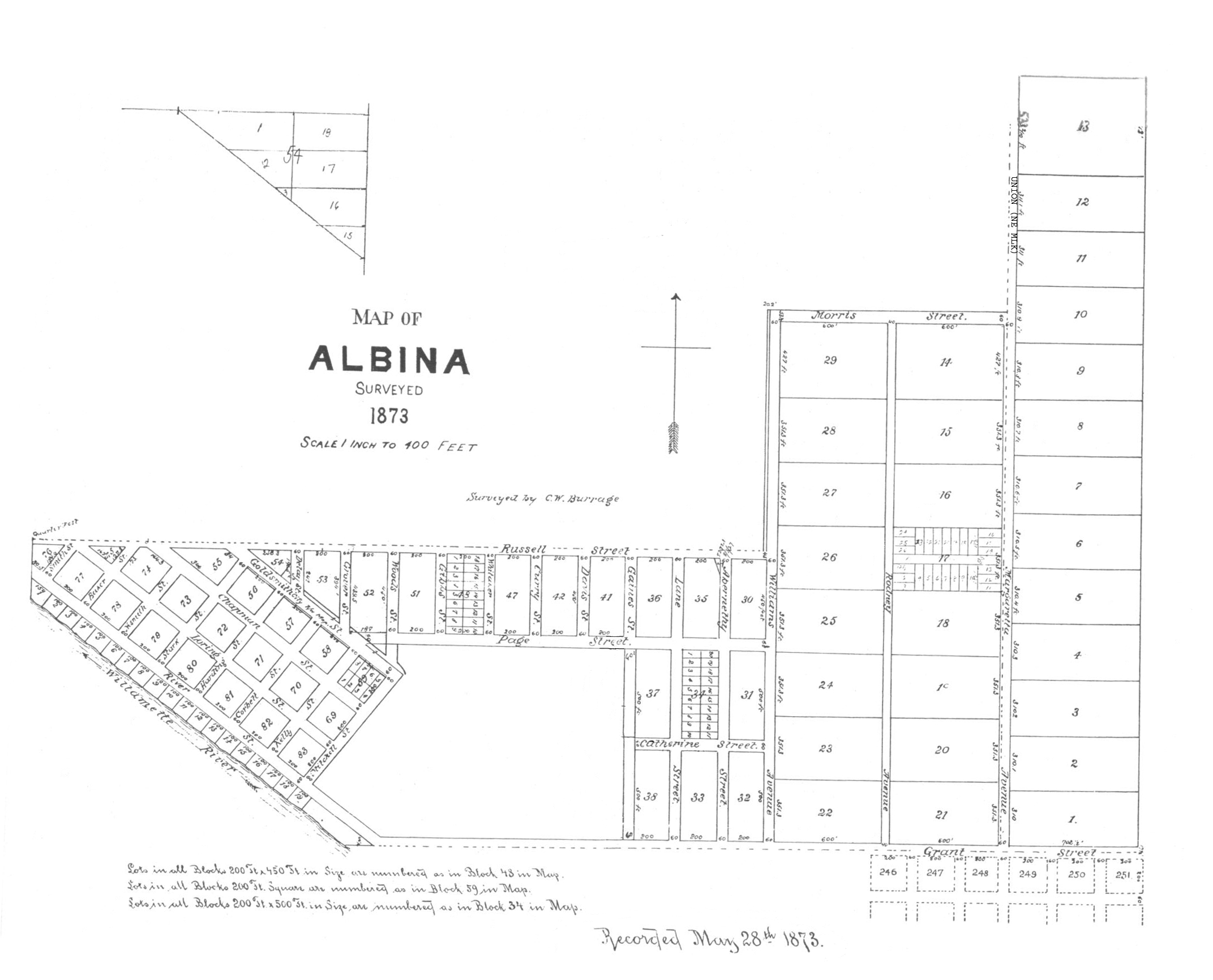

Portland, in 1873.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi49537

-

![Man in the top hat has been identified as (possibly) Benjamin Stark]()

Front and Stark Streets in Portland, 1852.

Man in the top hat has been identified as (possibly) Benjamin Stark Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi946

-

Sullivan's Gulch, now the I-84 corridor in Portland.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi91595

-

![]()

This may be Portland's first house after resettlement..

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, bb002974

-

The Portland Hotel in downtown Portland.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library

-

The Portland waterfront.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi28306

-

![]()

Portland harbor.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi3686

-

![]()

Cable cars in Portland Heights in the 1890s.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library

Related Entries

-

Albina area (Portland)

By the late 1880s, Albina, located across the Willamette River from Por…

-

![Ancient Order of Hibernians (Portland Division)]()

Ancient Order of Hibernians (Portland Division)

The Ancient Order of Hibernians is an Irish Catholic fraternal organiza…

-

Cast iron buildings in Portland

Portland is home to the second largest collection of cast iron architec…

-

![Great Light Way (3rd St., Portland)]()

Great Light Way (3rd St., Portland)

Portland’s Third Street reinvented itself as The Great Light Way in Jun…

-

![Housing Authority of Portland]()

Housing Authority of Portland

The Housing Authority of Portland was created in 1941 in response to th…

-

Irvington neighborhood, Portland

The Irvington neighborhood in northeast Portland began as an exclusive …

-

![Japantown, Portland (Nihonmachi)]()

Japantown, Portland (Nihonmachi)

Portland's Japantown, or Nihonmachi, is popularly described as having e…

-

![Ladd's Addition]()

Ladd's Addition

Ladd's Addition is a streetcar-era neighborhood in southeast Portland w…

-

![Metro Regional Government]()

Metro Regional Government

Metro is a regional agency that serves the urbanized portions of Multno…

-

![Olmsted Portland Park Plan]()

Olmsted Portland Park Plan

In the late nineteenth century, Portland's City Park (soon to be named …

-

![Port of Portland]()

Port of Portland

The Oregon Legislature created the current Port of Portland in 1970 by …

-

![Portland Park Blocks]()

Portland Park Blocks

While America's premier landscape architect, Frederick Law Olmsted, tra…

-

![Portland Penny]()

Portland Penny

The Portland Penny is an 1835 American copper penny that was used in an…

-

![Portland Public Market]()

Portland Public Market

Designated "market squares" were once common in American city plans, an…

-

![Portland Rose Festival]()

Portland Rose Festival

In 1905, when Portland Mayor Harry Lane addressed a crowd at the Lewis …

-

![Portland streetcar system]()

Portland streetcar system

The majority of Portland’s oldest neighborhoods owe their location and …

-

![South Portland/South Auditorium Urban Renewal Project]()

South Portland/South Auditorium Urban Renewal Project

In 1955, a Mayor’s Advisory Committee identified the blocks at the sout…

-

![Terra Cotta buildings in Portland]()

Terra Cotta buildings in Portland

Downtown Portland has an impressive collection of early twentieth-centu…

-

Urban Growth Boundary

Each urban area in Oregon is required to define an Urban Growth Boundar…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Abbott, Carl. Portland in Three Centuries: The Place and the People. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2011.

Lansing, Jewell. Portland: People, Politics, and Power, 1851-2001. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2003.

MacColl, E. Kimbark and Harry H. Stein. Merchants, Money and Power: The Portland Establishment, 1843-1915. Portland, Ore.: Georgian Press, 1988.