Jewish Pioneers: Becoming Oregonians

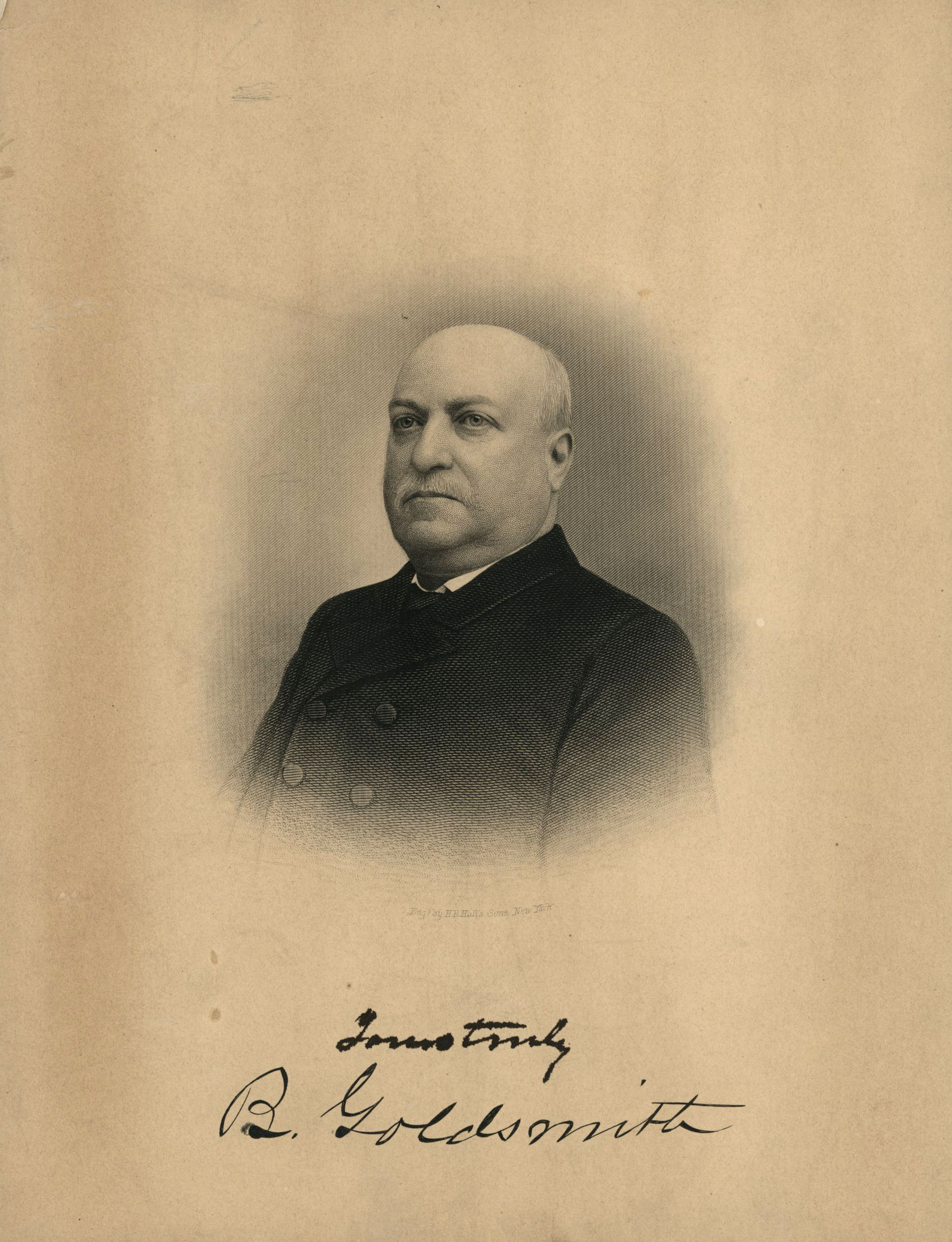

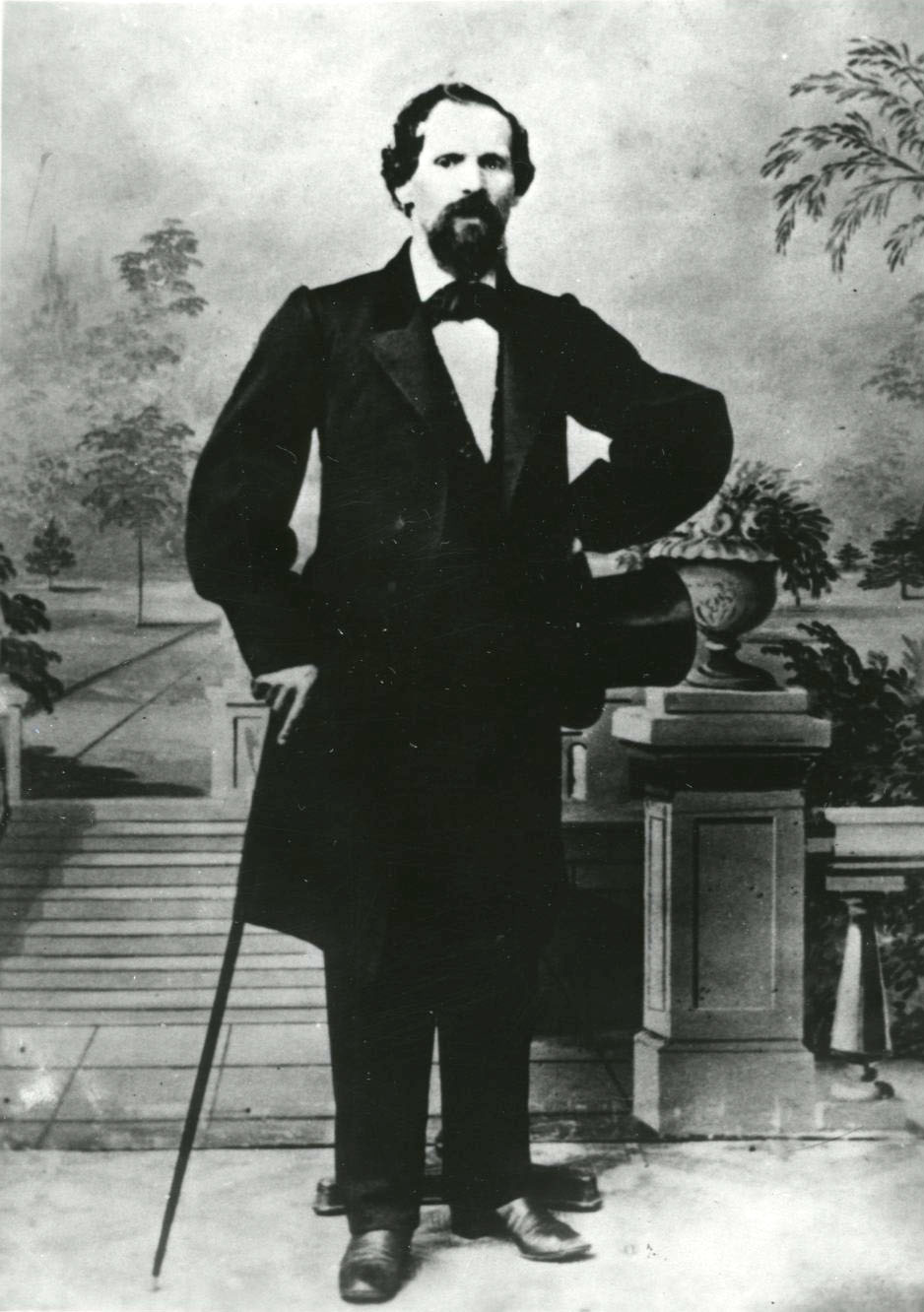

In 1869, Bernard Goldsmith, an immigrant Jew from Bavaria, was sworn in as the mayor of Portland. Two years later, he was succeeded in office by his friend, countryman, and coreligionist, Philip Wasserman, a former state legislator who would later serve on the city’s school board. Jews comprised only about 0.5 percent of Oregon’s population in the late nineteenth century, yet Goldsmith's and Wasserman’s political achievements were hardly unusual. At least seven Jewish mayors served towns across the state, and others held statewide office, served in the legislature, and sat on city councils and school boards. Between 1877 and 1911, Joseph Simon, a German Jew, served on Portland’s city council, in the state senate, in the U.S. Senate, and as Portland’s mayor.

Several factors fostered the acceptance of Jews suggested by these political achievements. The timing and composition of Jewish migration was key. Jews first arrived in Oregon in 1849, just years after the first Overland immigrations brought resettlers to the region. The vast majority, like Goldsmith and Wasserman, were immigrants from German lands; but rather than coming directly to Oregon from Europe, most spent years elsewhere in the United States before following the Gold Rush west and establishing merchandising networks anchored in San Francisco and extending north to Oregon. Those who settled in Oregon brought with them knowledge of English, familiarity with frontier society, and connections to San Francisco-based trade networks that positioned them well to join with fellow pioneers and help create new communities.

Concentration in trade, the most common occupation of Central European Jews, was a second factor that fostered acceptance. By the early 1850s, clusters of Jewish merchants operated in Jacksonville, supplying the booming mining town, and in Portland, where by 1860 approximately one-third of the 146 merchants were Jewish. Within the decade, there were similar clusters across the state, composed of merchants who often shared family and hometown ties. In Jacksonville, for example, at least four sets of Jewish brothers ran stores in the 1860s and 1870s; in the Willamette Valley, the five Hirsch brothers fanned out to operate stores in several towns.

Familial and hometown ties connected merchants to businesses in San Francisco and New York and to distribution, credit, and supply networks that enabled them to bring quality goods to remote frontier communities. These networks also supported investment in their stores, often among the first brick buildings in new towns, helping to promote their businesses while fostering community stability and putting their localities on the map. In eastern Oregon, Jewish pack-train operator turned merchant, Henry Heppner, became the namesake of the town he founded. After a career as a peddler in gold country, Aaron Meier opened his first store in Portland in 1857; fifteen years later, he joined forces with brothers Emil and Sigmund Frank to found Meier & Frank, the state's premier department store through the twentieth century.

Oregon’s ethnic landscape was also critical to Jewish acceptance and inclusion during this period. With settlers’ racial anxieties focused on Native Americans and, later, on Asians, Jews—with their European origins, American experience, and English language skills—were generally viewed as white pioneers, not as foreign interlopers. Incidents of antisemitism, while not entirely absent, were relatively rare. Engagement in town building, operating pack trains, and fighting in the region’s Indian Wars fostered the inclusion of Jews in organizations such as the Native Sons of Oregon, which celebrated pioneer history, and in fraternal, civic, and business organizations such as the Masons and chambers of commerce. The Jewish civic leadership fostered by this high level of acceptance would continue in the next generation, when notable figures included Ben Selling, who served in the 1910s as the speaker of the Oregon House and president of the Oregon Senate, and Julius Meier, who was overwhelmingly elected governor in 1930 despite increasing national and local antisemitism.

Emerging Jewish Community: Portland

Although Jews were in Oregon from 1849, it was not until nearly a decade later that they organized communal institutions. The preponderance of single men, their focus on establishing businesses, and their commitment to engaging in broader civic life delayed the emergence of religious congregations. Moreover, individuals attracted to the West were generally not those who prioritized religious observance; the requisites for strict practice, such as the quorum of ten men needed for a service and the availability of kosher meat, were lacking on the frontier.

Family formation was a major impetus to community building. Many Jewish pioneers, arriving as single men, delayed marriage until after they had established businesses and traveled to San Francisco or even to New York or Europe to find Jewish partners. It was not until 1858, after the arrival of several Jewish women and the birth of the first child, that a Jewish congregation, Beth Israel, formed in Portland. In 1861, the congregation erected the state’s first synagogue, with seating for two hundred; its consecration attracted many non-Jewish Portlanders and the attention of the press.

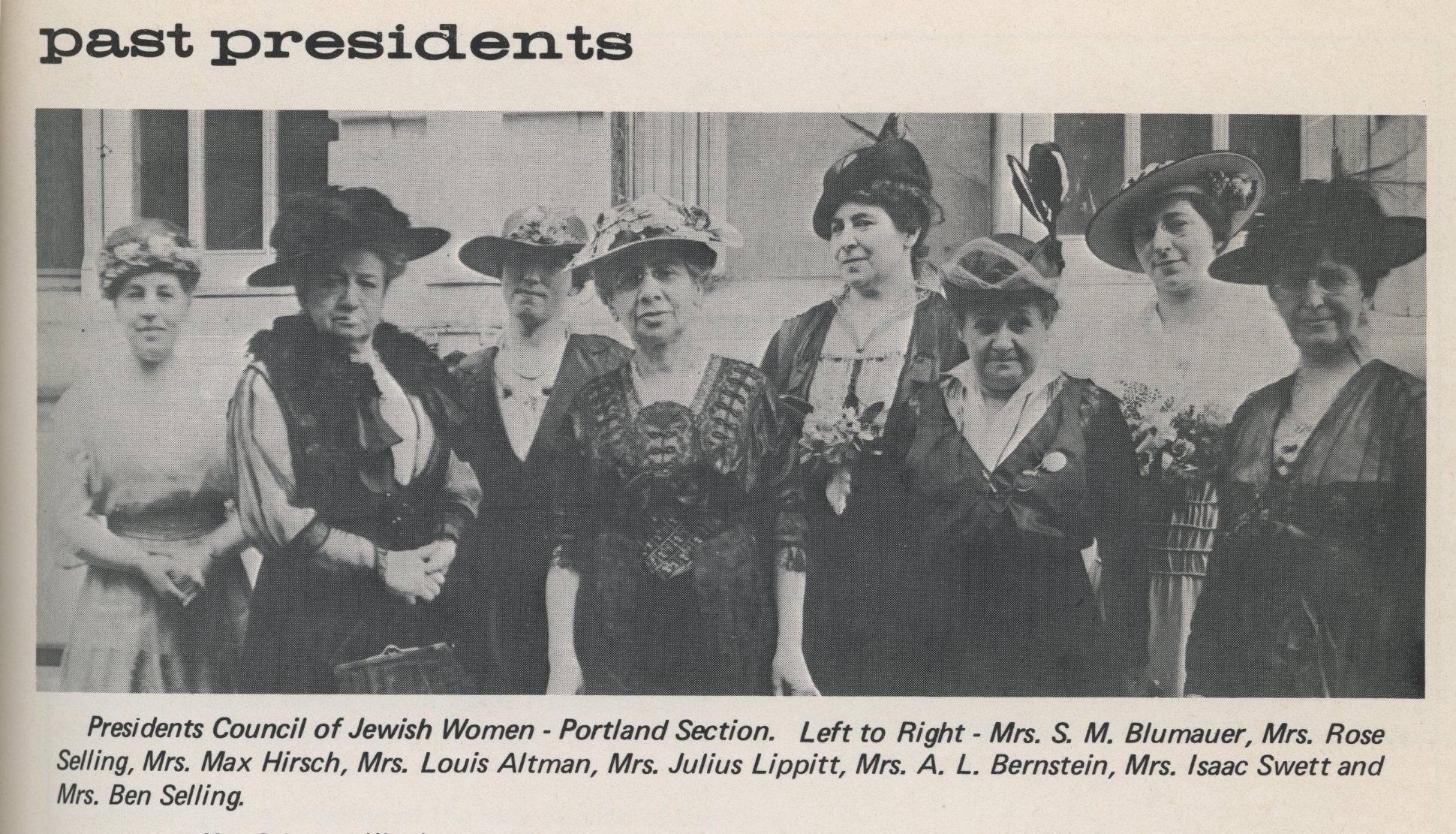

With Portland’s Jewish population nearing 500 in 1869, a second congregation, Ahavai Sholom, was founded by a splinter group of eight men from Posen, Prussia. Ahavai Sholom would emerge as a Conservative congregation, striking a balance between orthodoxy and the modern innovations of Reform. Beth Israel, after considerable discord over religious practice in the 1860s and 1870s, gravitated toward Reform. By the end of the century, Beth Israel had built a grand, two-towered synagogue that seated 750 people, a fitting structure for a congregation associated with Portland’s Jewish political and business elite. Its status was further elevated by its rabbis, Stephen S. Wise, who served at Beth Israel from 1900 to 1906, and Jonah Wise, who served from 1907 to 1926. Both rose to national prominence.Beyond the congregations, Portland Jews created a broader institutional structure. Following a Jewish tradition of taking care of their own, they formed the First Hebrew Benevolent Association in 1859, a mutual aid society that extended loans to members and nonmembers and that paid for health care, funeral costs, and other emergencies. An organization that would incorporate in 1874 as the First Hebrew Ladies Benevolent Society had begun a decade earlier to provide assistance to Jewish women in need and to make home visits to sick and bereaved community members. In 1866, a Portland lodge of the B’nai B’rith formed. It functioned as both a social club and mutual insurance organization and would be joined by several additional lodges before the end of the century. A Young Men’s Hebrew Association (YMHA), a Jewish counterpart to the YMCA, was established in 1880 to provide cultural and educational programs, including lectures, debates, and a library. And in 1896, a younger generation of mostly native-born upper and middle-class Jewish women connected to Congregation Beth Israel formed the Portland Section of the National Council of Jewish Women (NCJW), a progressive organization that emphasized study and service; the group would play a critical role in aiding newcomers to the community.

Beyond Portland: Waning Communities

Although the first known Jewish religious service in Oregon took place in Jacksonville in celebration of the High Holidays in 1856, and there is evidence of holiday observances and life-cycle rituals in other towns across the state, no lasting congregations or other Jewish institutions emerged outside of Portland in the nineteenth century, aside from a burial society in Albany that served communities from Eugene to Salem. Jews who lived in in the Willamette Valley or in more remote parts of the state often traveled to Portland to celebrate High Holidays or life-cycle events. Such trips provided opportunities to conduct business and to meet potential marriage partners.

The arrival of women and the growth of families in the late nineteenth century increased the population of Jews in cities and towns beyond Portland, but those communities quickly waned. Jacksonville’s Jewish community, which in the 1860s included a dozen merchants, several with families, dwindled after the gold rush had run its course. A few individuals remained, but most had moved on by the 1870s. Jewish communities in eastern Oregon towns such as Baker eventually followed a similar course. Although the decline in population followed broader boom-and-bust patterns, the exodus was accelerated among families that longed to participate in a larger Jewish community and provide their children with a Jewish education. Such was the case of the Durkheimer family, for example. Julius Durkheimer ran stores in Baker, Prairie City, Canyon City, and Burns and served on the school board and then as mayor of Burns. Yet, fulfilling a promise to his wife, who longed to be closer to family and a Jewish community, they moved to Portland ten years after their marriage.

Even in less remote areas, families that traveled to Portland for holidays and life-cycle rituals eventually moved there permanently. Exceptional were Salem, Eugene, and Astoria, where small Jewish communities persisted throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, although no formal congregations emerged in those towns until the 1930s and 1940s. Salem built a synagogue in 1948, Eugene built one in 1952, and a congregation functioned in Astoria from 1940 to 1963. These communities were too small, however, to support professional clergy, so visiting rabbis were brought in from Portland to officiate for some services and life-cycle rituals.

Newcomers from Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean

Between 1880 and 1924, the mass migration of roughly 2.5 million East Europeans to the United States dramatically altered the American Jewish landscape. Compared to Germans who had arrived earlier, Eastern Europeans tended to be far more traditional in their religious practices. They were predominantly craft or industrial workers (particularly garment workers) and more receptive to socialist and Zionist ideologies than were their American coreligionists. Historians have emphasized the fraught relationship between these immigrants and established American Jews, who often regarded the newcomers as backward and insular and whose presence they feared might stoke antisemitism. These feelings were mitigated by a strongly felt obligation to provide assistance to them, leading established communities to create aid programs that preached rapid Americanization.

The opportunity structures and migration patterns that brought Eastern European Jews to Oregon muted some of these tensions. Eastern European Jews reached the Pacific Northwest gradually and in relatively small numbers; even at the peak of the influx in the 1920s, Portland’s Jewish population remained below 10,000. In addition, a process of self-selection among these migrants and a contemporaneous influx of Sephardic Jews from the Mediterranean Basin created a different dynamic.

Although the vast majority of Eastern European Jews immigrating to the United States during this period were laborers, the first group to arrive in Oregon were aspiring farmers. Am Olam (Eternal People) was one of several idealistic Jewish groups to emerge in early-1880s Russia, as deteriorating political and economic conditions triggered the mass emigration of Jews. Am Olam combined socialist ideologies popular among Russian revolutionaries with an embrace of modern life that included rejection of traditional religious practice and a back-to-the-land ethos that they believed would make Jews productive in the eyes of the world and lead to the elimination of antisemitism.

Am Olam chapters established colonies in American locations from North Dakota to Louisiana to New Jersey in 1881-1882. The Odessa chapter, consisting principally of young men, established New Odessa Colony on 900 acres of forested land near Roseburg. Numbering between forty and fifty individuals by 1883, colonists lived communally, earning money by supplying staves for railroad construction. They engaged in a strict regimen that included the study of philosophy, the rejection of traditional religious practice as inconsistent with their modern outlook, and an experimentation in gender equality, including equal sharing of labor. After five years, ideological divisions led to the colony’s dissolution, and its members dispersed.

Veterans of sister colonies in the Dakotas were among the Eastern European Jews to arrive in Portland in the mid to late 1880s, and their modern outlook and American experience influenced key community institutions. Israel Bromberg, for example, who came to Portland from the Painted Woods, North Dakota, colony, played a key role in shaping the Portland Hebrew School’s modern curriculum, with its emphasis on Americanization and cultural Zionism. Joseph Nudelman, a veteran of several colony experiments, was a founder and leader of Congregation Shaarie Torah.

With little industry in Oregon and few opportunities for garment workers, the vast majority of Eastern European Jewish newcomers to Oregon were aspiring merchants, often with experience in petty trade or peddling gained in Russia and during sojourns in America. Many opened small shops in South Portland. Like their German predecessors, these early Eastern European immigrants tended to be flexible in religious observance, and the first Russian Jewish congregations in Portland in the 1890s were not strictly orthodox. Congregations Neveh Zedek and Talmud Torah advertised choirs, instrumental music, and sermons in English and German—none of these typical of an immigrant shul (traditional synagogue). Only after 1900, as relatives and acquaintances of Jews who had arrived earlier immigrated directly to Portland, were explicitly orthodox congregations founded: Shaarie Torah in 1902, Linath Hazedek in 1914, and Kesser Israel in 1916.

Sephardim from the Mediterranean Basin also began to arrive in Oregon. Sephardim are Jews who trace their lineage to Spain and speak Ladino (Judeo Spanish), but the term is used loosely to refer to Jews from throughout the Mediterranean. Although Sephardim were a key component of the American Jewish community during the colonial period, they had become a small minority by the mid-nineteenth century. While their renewed immigration in the early twentieth century was overshadowed by the flood of Eastern Europeans who arrived in the United States, in Oregon Sephardim made up a more significant portion of the newcomers and had more impact on the broader community. Portland Sephardim were an offshoot of Seattle’s community, the second largest in the country, at about 2,000 in the 1920s. They began to arrive in Portland in 1909 and within a year had a program of regular religious services. By 1916, they had founded congregation Ahavath Achim and developed a subcommunity in South Portland.

Old South Portland

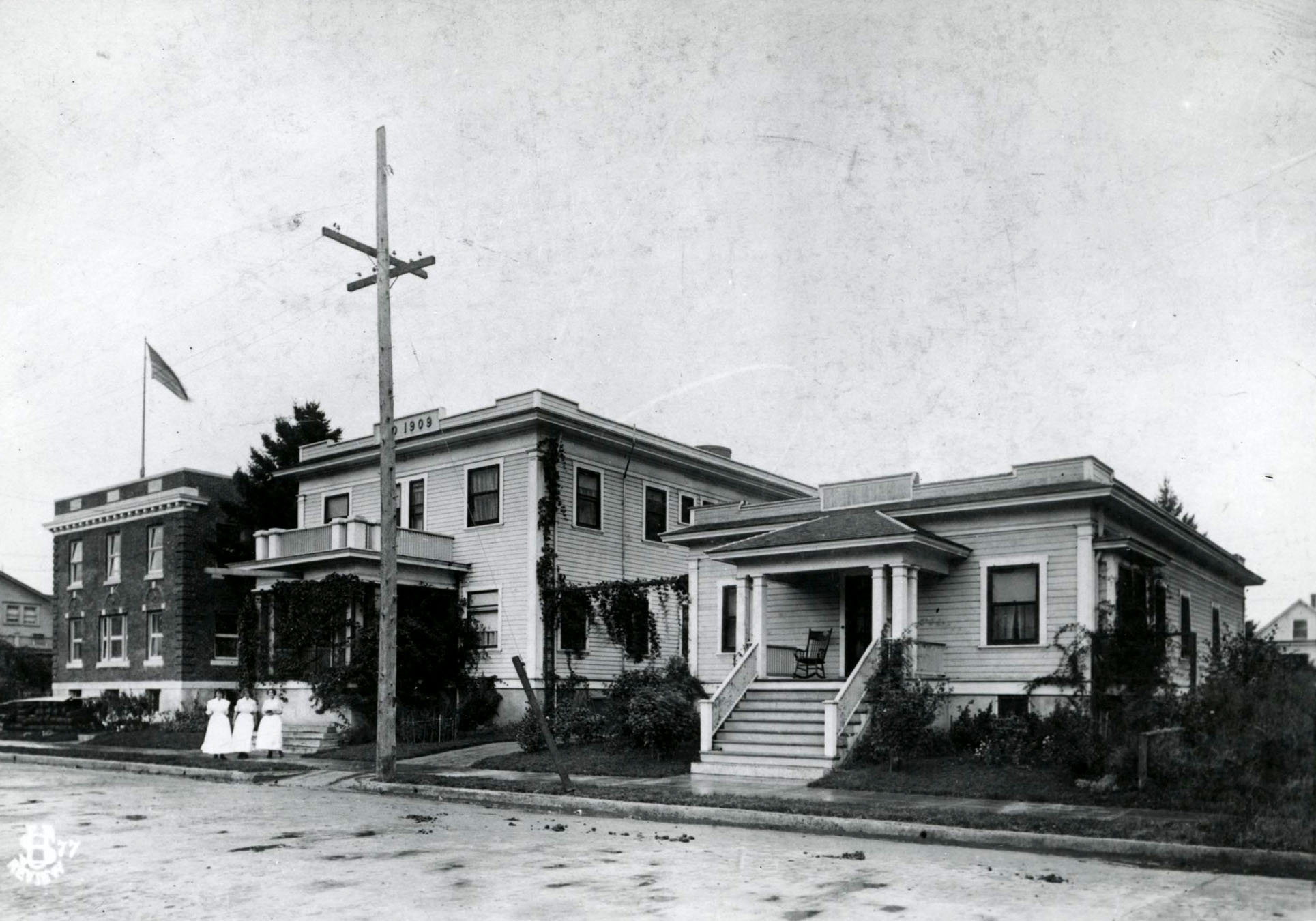

Just south of downtown, a neighborhood later known as Old South Portland was home to both Eastern Europeans and Sephardim and to the shops and institutions that served them. Motivated by the Progressive Era settlement house movement and with the enthusiastic support of Rabbi Stephen Wise, the Portland Section of the National Council of Jewish Women established Neighborhood House in 1905, after studying modern philanthropy and the social problems of immigrants. Considered the heart of the community, Neighborhood House provided classes, clubs, athletic facilities, and social services for Jews and other residents. Ida Loewenberg, a professional social worker and daughter of a prominent family, led Neighborhood House for over three decades, beginning in 1912.

Children of Eastern European and Sephardic immigrants who came of age in the 1920s and 1930s remember the neighborhood as insular and nurturing. It was a time of increased antisemitism locally and nationally, and the neighborhood and its institutions provided a respite. Beginning in the 1920s and 1930s, and accelerating in the 1940s and 1950s, families moved to more prosperous areas of the city. Still, South Portland remained a Jewish institutional hub, with ethnic shops, the Portland Hebrew School, the Jewish Home for the Aged, Neighborhood House, the B’nai B’rith Building (later the Jewish Community Center), and all but two of the city’s congregations.

In 1958, Portland voters approved an urban renewal plan that would result in the razing of the South Portland neighborhood and nearly all of its Jewish institutions by the early 1970s. As the community mourned this loss, a new institutional cluster emerged in southwest Portland, anchored by a new Jewish Community Center and conservative congregation Neveh Shalom, the result of a merger between Neveh Zedek and Ahavai Sholom.

Expansion and Regeneration: The 1970s and Beyond

Despite the arrival of a small number of refugees and Holocaust survivors at midcentury, Oregon’s Jewish population had held steady for decades, between 7,000 and 8,000 people. By the late 1970s, however, that number grew to 10,000, then to 25,000 in 1999. By 2010, 40,000 to 48,000 Jews lived in Oregon, 36,000 to 42,000 of them in the Portland metropolitan area. Between 1970 and 2015, growing congregations in Eugene and Salem hired fulltime rabbis and moved to larger buildings. New congregations were founded in Eugene, Bend, Ashland, and Corvallis, and small, informal communities formed in Klamath Falls, Coos Bay, Roseburg, and on the North Coast. Chabad, an Orthodox Hasidic movement focusing on outreach within the Jewish community, set up centers in many of these cities and towns, as well as in Portland.

The increase in the Jewish population was part of a broader migration of young, well-educated newcomers to Oregon, particularly to Portland, attracted by the region’s reputation for livability, progressiveness, and innovation. Jews were not only overrepresented among those drawn by these changes, but were among the key players instigating them. As was the case nationally, Jewish Oregonians had faced antisemitic exclusions from country clubs, professional firms, and high school and college fraternities and sororities through the 1950s and well into the 1960s. Such experiences led to a community embrace of the fight against prejudice and discrimination.

Rabbis such as Temple Beth Israel’s Julius Nodel (1950-1959) and Emanuel Rose (1960-2006), the Portland B’nai B’rith and Council of Jewish Women chapters, and a number of individuals, including lawyer (later federal judge) Gus Solomon, Oregon Senator Harry Kenin, Urban League and City Club President David Robinson, and Oregon Senator Richard Neuberger (later U.S. senator) were prominent in civil rights campaigns that helped shift the state away from its historic racism and toward a more progressive agenda. Neuberger was also an early leader of Oregon’s environmental movement; Mayors Neil Goldschmidt and Vera Katz were leaders in the revitalization of Portland’s downtown and neighborhoods; and members of the Schnitzer family (Arlene and Harold and, later, their son Jordan) played a critical role in the development of the arts community, including the Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall in Portland and the University of Oregon's Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art in Eugene.

The three longtime rabbis of Oregon’s largest synagogues—Joshua Stampfer (Neveh Shalom, 1953-1993), Emanuel Rose (Beth Israel, 1960-2006), and Yonah Geller (Shaarie Torah, 1960-2000)—modernized and revitalized their communities. They reached out to growing numbers of Jewish Oregonians who, like their nineteenth-century predecessors and their non-Jewish contemporaries drawn to the Pacific Northwest, were less traditionally religious than those they had left behind in larger eastern, midwestern, and California communities. Such newcomers, along with younger generations of longtime Oregon Jewish families, provided constituencies for an expanding array of secular and cultural Jewish events and organizations, ranging from the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education to an annual Portland Jewish Film Festival. New congregations, both in Portland and around the state, are increasingly affiliated with liberal streams of Judaism such as Reconstructionism and Renewal, which welcome diverse Jews, including interfaith partners and members of the LGBTQ community.

-

![]()

National Council of Jewish Women, Portland chapter, c.1910.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi87506

-

![Rabbi Henry J. Berkowitz (center), Rabbi Herbert Parzen (far left), Dr. Jonah Wise (right center), Rabbi Samuel Koch (rar right), S.M. Tonkin (front left), and attorney David Solis-Cohen]()

Jewish leaders in Pacific Northwest.

Rabbi Henry J. Berkowitz (center), Rabbi Herbert Parzen (far left), Dr. Jonah Wise (right center), Rabbi Samuel Koch (rar right), S.M. Tonkin (front left), and attorney David Solis-Cohen Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi97692, photo file 1858

-

![]()

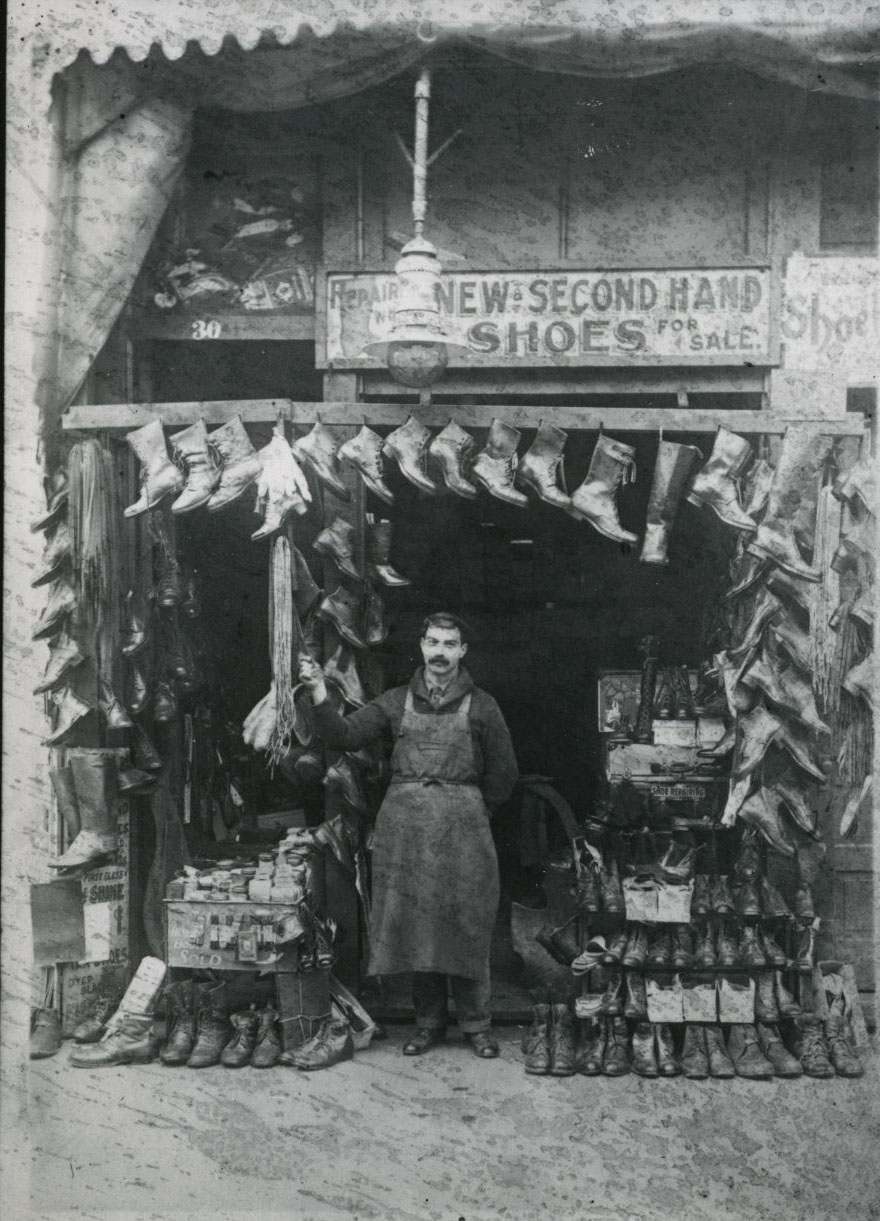

Nessim Menashe shoe store, West Burnside, Portland, c.1916.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 023972

-

![]()

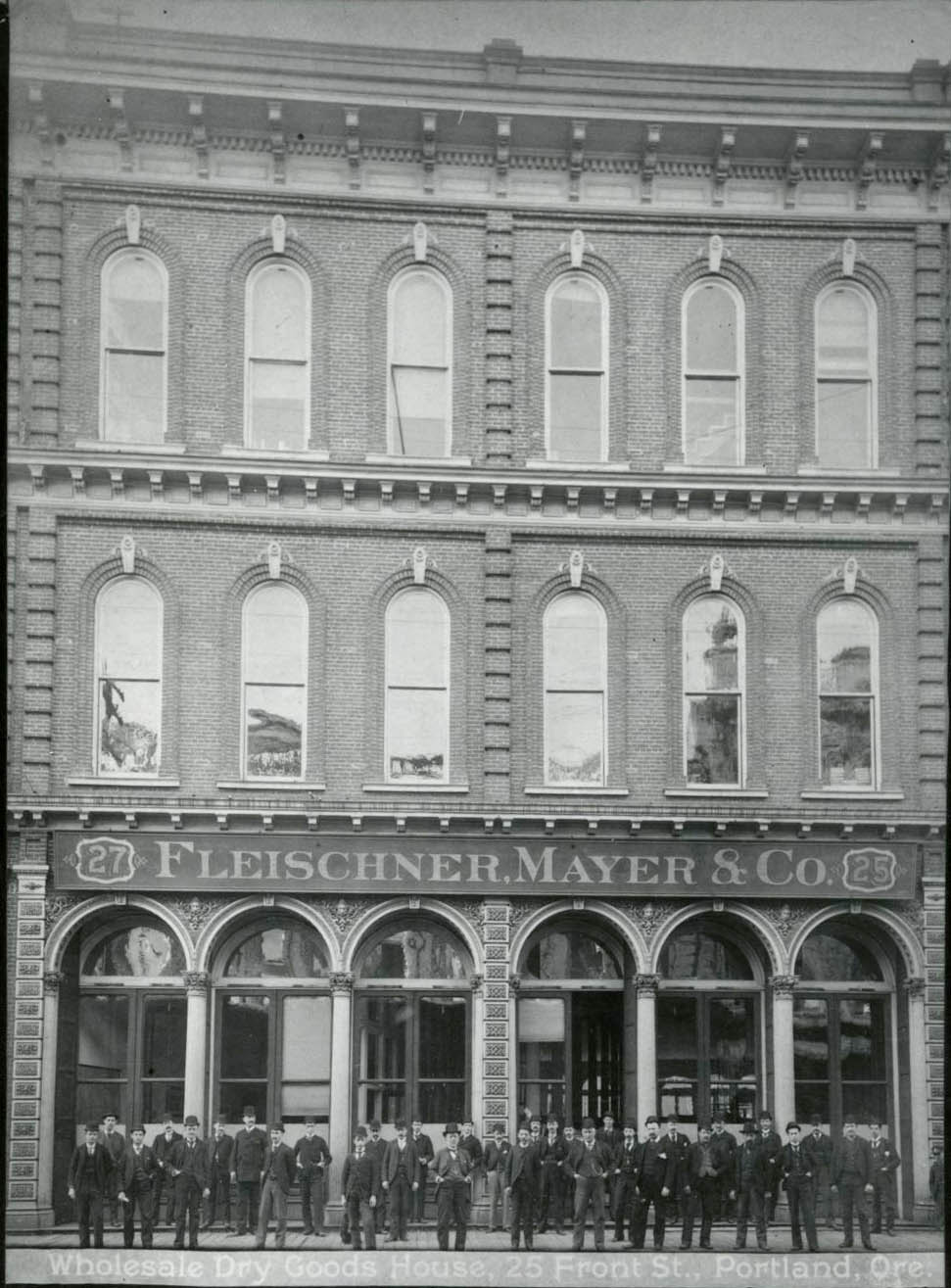

Fleischner, Mayer, and Co., NW First Ave., Portland.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 017945

-

![1888 Beth Israel synagogue at SW 12th & Main St., Portland, burned 1923.]()

Beth Israel synagogue, 1888 bldg, exterior, bb008629.

1888 Beth Israel synagogue at SW 12th & Main St., Portland, burned 1923. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Libr., bb008629

-

![]()

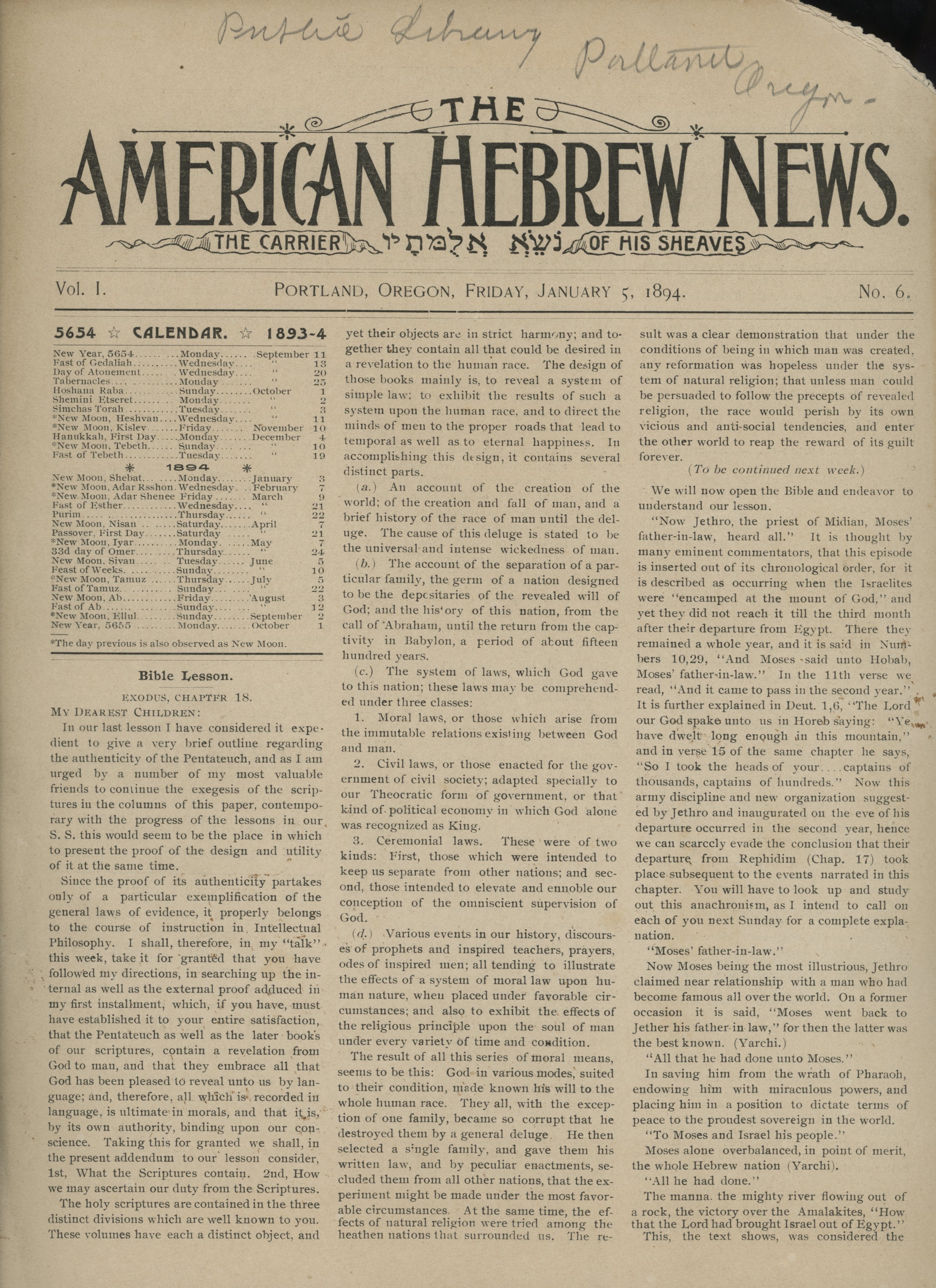

Front page of the American Hebrew News, Jan. 5, 1894, published in Portland.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

-

![]()

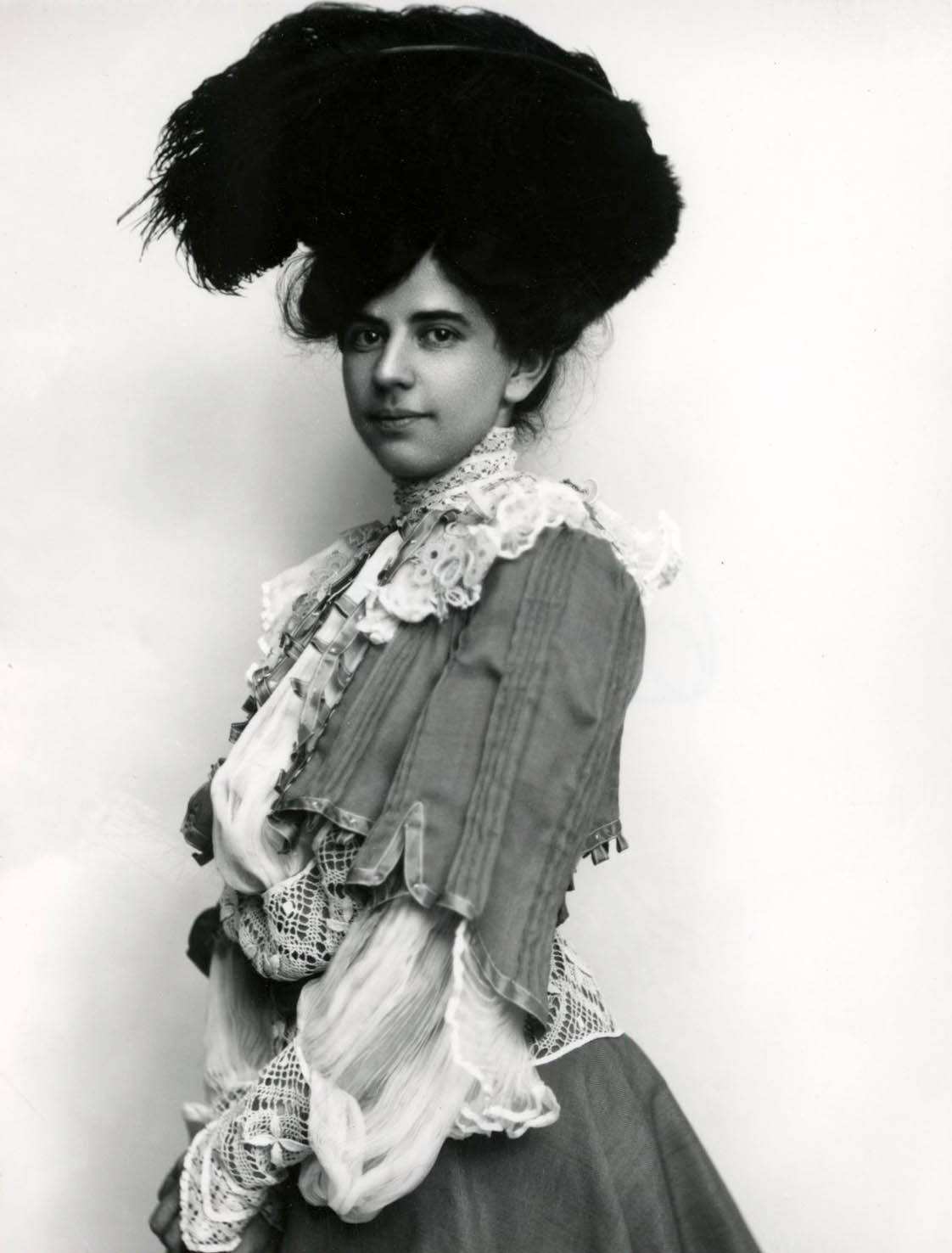

Gertrude Hirsch, daughter of Oregon State Treasurer Edward Hirsch, Salem, 1903.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Cronise 0006G041

-

![]()

Oregonians, including Maier Hirsch, attending the Republican Convention in Maryland, 1864.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi11299

-

![]()

Bernard Goldsmith, mayor of Portland, c.1860s.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi76711, photo file448

-

![]()

South Portland, c.1867.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi1609, photo file 1657

-

![]()

Julius Durkheim store, Burns, Oregon, c.1890. Durkheim stands with hand truck..

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bc004889, photo file 188a

-

![]()

Lou (or Lulu) Hirsch, daughter of Edward, Salem, 1892.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 0177G031

-

![]()

Sunday School pageant, Temple Beth Israel, Portland, 1898.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi25946, photo file 1858

-

![]()

Portland Jewish Community Center, c.1910.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 53303, photo file 1657

-

![]()

Ben Selling at the groundbreaking for Neighborhood House, c.1913.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., from Jewish Hist. Society of Oregon, Orhi87401, photo file 1657

-

![]()

Neighborhood House, SW 2nd Ave and Woods St., Portland.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., from Jewish Hist. Society of Oregon, Orhi87402, photo file 1657

-

![]()

Citizenship class, Neighborhood House, Portland.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., from Jewish Hist. Society of Oregon, Orhi87399, photo file 1657

-

![]()

A cooking class at the Neighborhood House, SW 2nd Ave, Portland, 1914.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 023271

-

![]()

Well-baby clinic at Neighborhood House.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., from Jewish Hist. Society of Oregon, Orhi87398, photo file 1657

-

![(Grand Master of the Masons)]()

Jacob Mayer, co-founder of Fleischner, Mayer, & Co..

(Grand Master of the Masons) Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., photo file 731

-

![]()

Mayor Phillip Wasserman, Portland.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 25709, photo file 1096

-

![]()

Council of Jewish Women, c.1925.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 360N559s

-

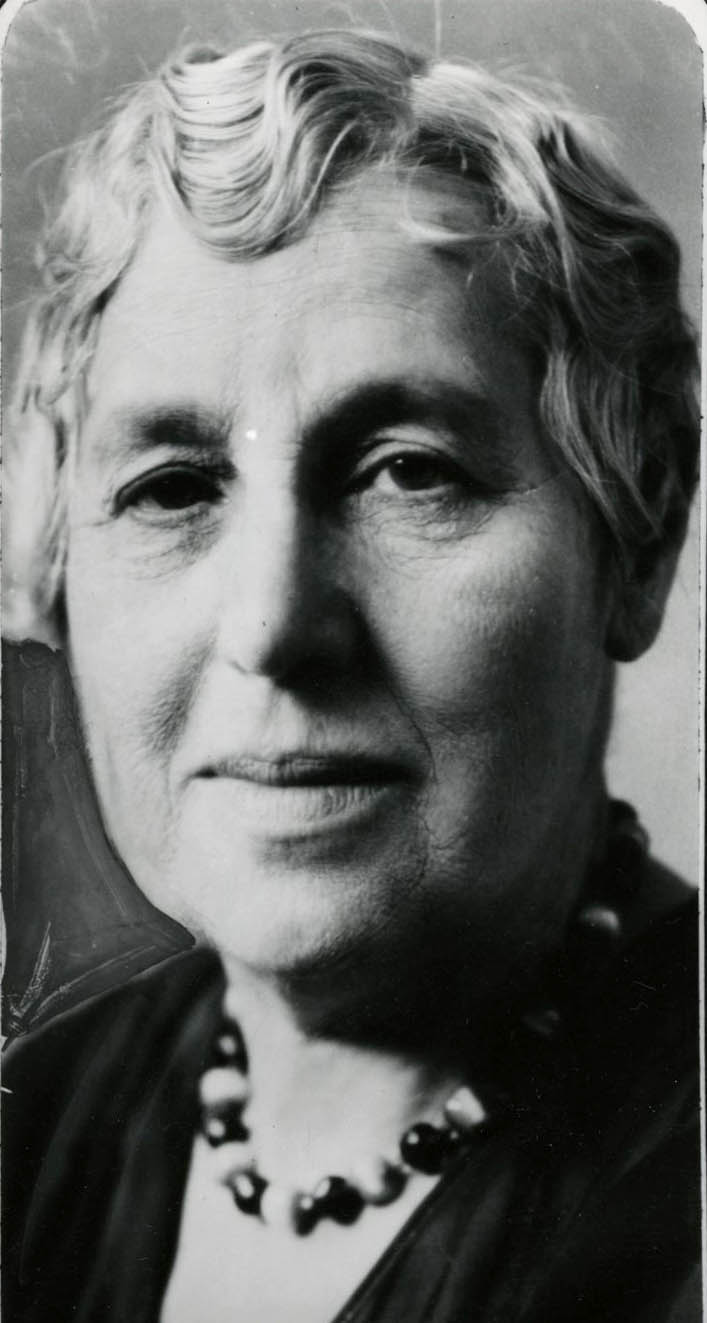

![]()

Blanch Blumauer, Honorary Vice President of the National Council of Jewish Women, Portland, 1930.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Journal, 000864

-

![]()

Julius Meier and Aaron Frank, with Hoffman and Dinwiddle contractors building addition to Meier & Frank, July 1930.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Oregonian, 54212, photo file 739a

-

![]()

Julius Meier (center) and family, at Menucha, November 1930.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Journal, photo file 739a

-

![]()

Inauguration of Gov. Julius Meier, Jan. 31, 1931.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Journal, photo file 739a

-

![]()

Gov. Julius Meier, at en event with the LA Breakfast Club, Dec. 1931.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Journal, photo file 739a

-

![]()

Gov. Julius Meier, November 1931.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Journal, photo file 739a

-

![]()

Meier and Frank employees at Menucha. Julius Meier in center, with tie..

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi89620, photo file739a

-

![]()

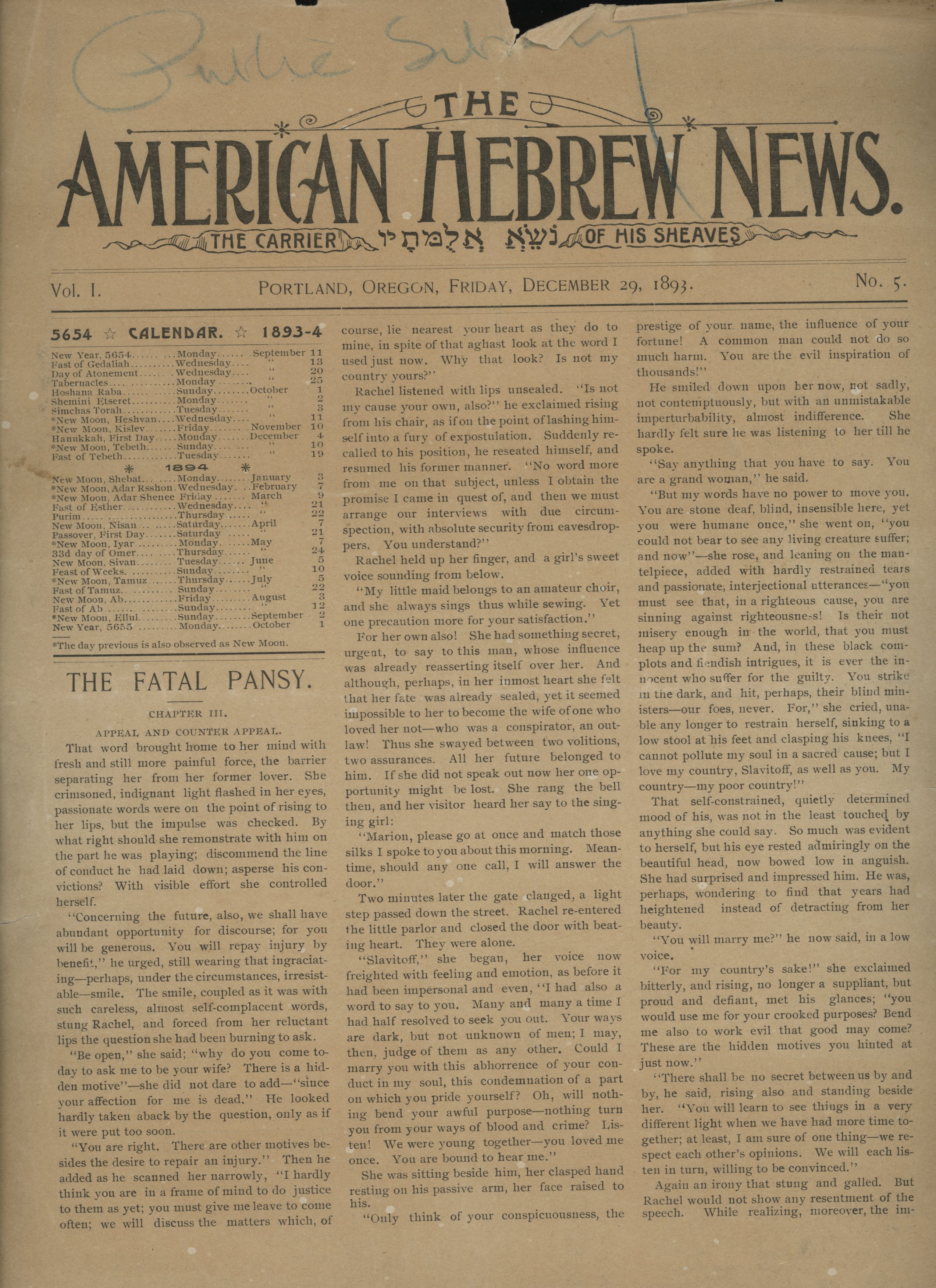

Front page of the American Hebrew News, Dec. 29, 1893, published in Portland.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

-

![]()

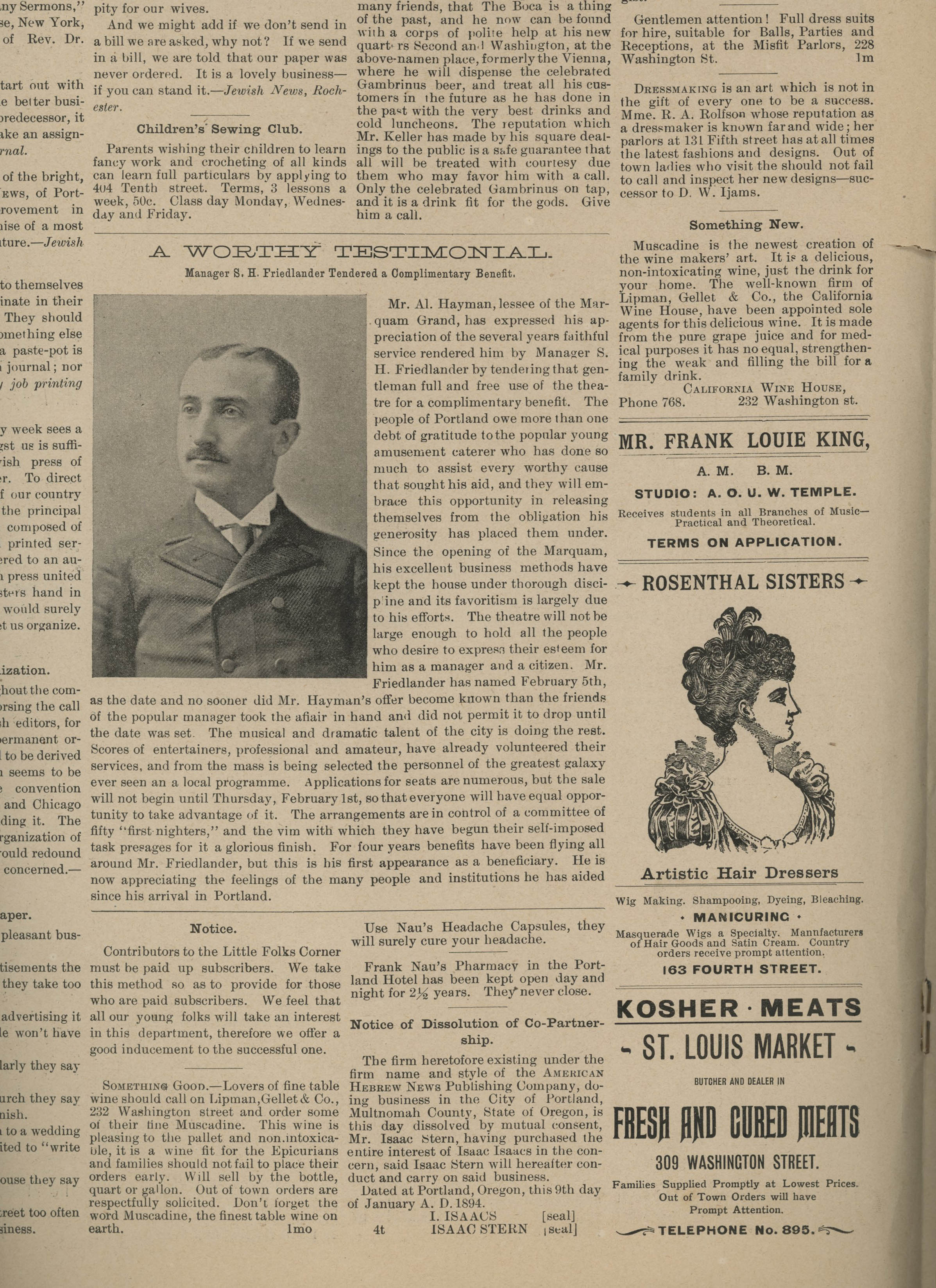

Ads in the American Hebrew News, January 19, 1894.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

-

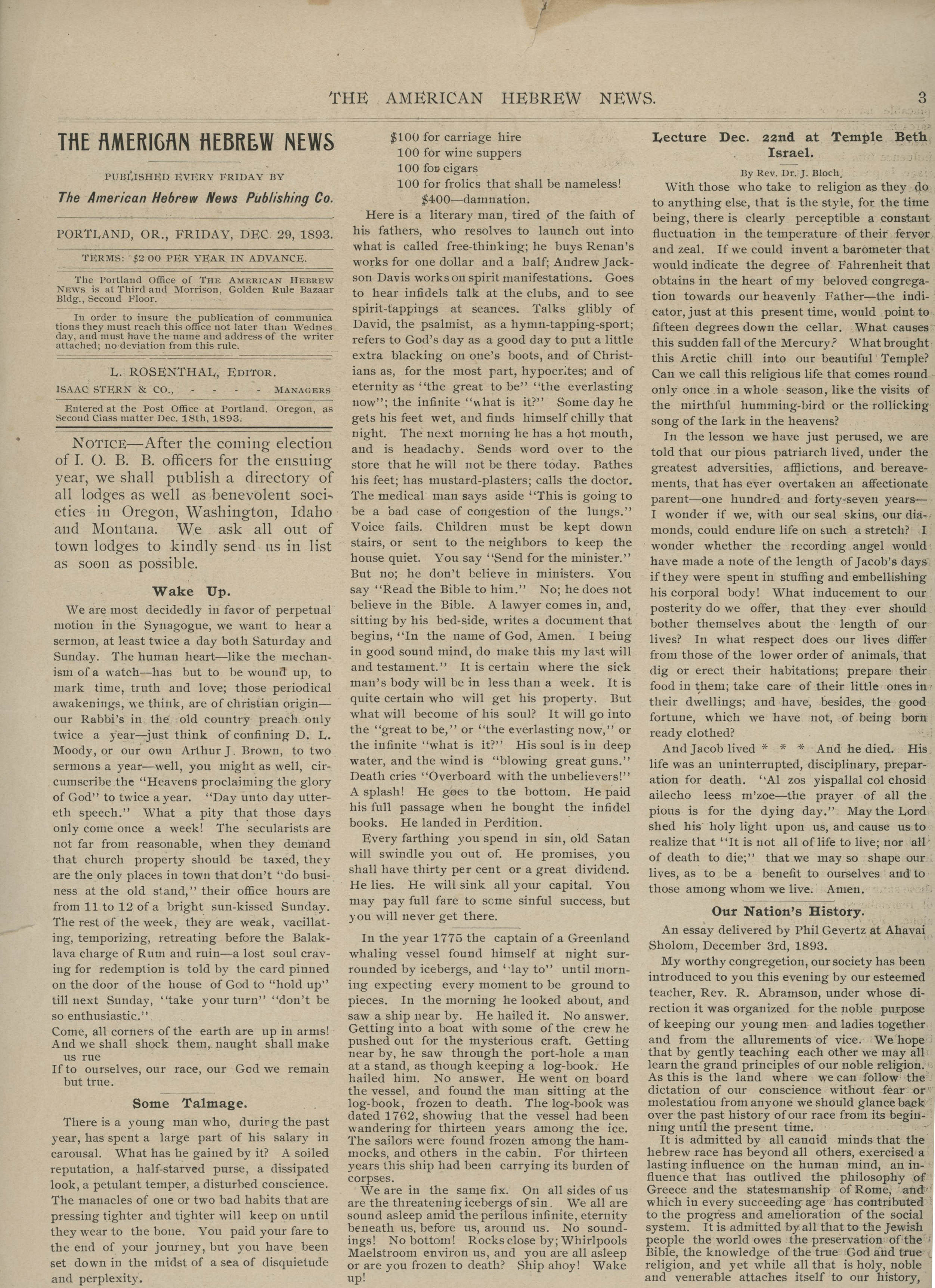

![]()

First page of American Hebrew News, Dec. 29, 1903.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

-

![Destroyed by fire in 1923.]()

Temple Beth Israel, SW 12th and Main, Portland, 1888.

Destroyed by fire in 1923. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 53711, photo file 1858

-

![Rebuilt Temple Beth Israel, Portland.]()

Temple Beth Israel, Portland, bb007121.

Rebuilt Temple Beth Israel, Portland. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb007121

-

![Interior of Temple Beth Israel, 1972.]()

Beth Israel, temple, interior, 1972, bb008623.

Interior of Temple Beth Israel, 1972. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Libr., bb008623

-

![Torn down in 1964.]()

Neveh Zedek Synagogue, 6th and Hall, Portland.

Torn down in 1964. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Gifford, 10688e, photo file 1858

-

![Neveh Shalom synagogue at SW 13th, Portland, prior to demolition, Jan. 1963.]()

Nevah Shalom synagogue, old, exterior, 1963, bb008621.

Neveh Shalom synagogue at SW 13th, Portland, prior to demolition, Jan. 1963. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Libr., bb008621

-

![]()

Cantor and choir, Shaarie Torah, Portland, September 1927.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., from Jewish Hist. Society of Oregon, Orhi909911, photo file 1858

-

![The Sachs brothers immigrated from Germany in the 1860s and opened a store to serve the many gold miners in the region.]()

Sachs Brothers Dry Goods Store, Jacksonville, Oregon.

The Sachs brothers immigrated from Germany in the 1860s and opened a store to serve the many gold miners in the region. Courtesy University of Oregon Libraries

Related Entries

-

![Am Olam]()

Am Olam

In response to pogroms in the early 1880s, two reform-minded organizati…

-

![Ben Selling (1852-1931)]()

Ben Selling (1852-1931)

Ben Selling—an early Portland merchant, elected official, and philanthr…

-

![Congregation Ahavath Achim]()

Congregation Ahavath Achim

Founded in Portland in 1916, Ahavath Achim was the first Sephardic Jewi…

-

![Congregation Beth Israel]()

Congregation Beth Israel

Congregation Beth Israel (CBI) is the oldest and most prominent Jewish …

-

![Congregation Neveh Shalom]()

Congregation Neveh Shalom

Congregation Neveh Shalom is the name of both a synagogue and the congr…

-

![Congregation Shaarie Torah]()

Congregation Shaarie Torah

Shaarie Torah is the name of both a synagogue in northwest Portland and…

-

![Jonah B. Wise (1881-1959)]()

Jonah B. Wise (1881-1959)

Rabbi Jonah B. Wise led Congregation Beth Israel, Portland’s oldest and…

-

![Julius L. Meier (1874-1937)]()

Julius L. Meier (1874-1937)

Julius Meier served as Oregon’s governor from 1931 to 1935 during the d…

-

![Neighborhood House]()

Neighborhood House

Neighborhood House, a settlement house and social services center origi…

-

![South Portland/South Auditorium Urban Renewal Project]()

South Portland/South Auditorium Urban Renewal Project

In 1955, a Mayor’s Advisory Committee identified the blocks at the sout…

-

![Stephen S. Wise (1874-1949)]()

Stephen S. Wise (1874-1949)

Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, one of the most significant American Jewish lead…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Eisenberg, Ellen. Embracing a Western Identity: Jewish Oregonians, 1849-1950. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2015.

Eisenberg, Ellen. The Jewish Oregon Story, 1950-2010. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2016.

Cline, Robert Scott. Community Structure on the Urban Frontier: The Jews of Portland Oregon, 1849-1887. Masters Thesis, Portland State University, 1982.

Lowenstein, Steven. The Jews of Oregon, 1850-1950. Portland: Jewish Historical Society of Oregon, 1987.

Miranda, Gary. Following a River: Portland’s Congregation Neveh Shalom, 1869-1889. Portland, Ore.: Congregation Neveh Shalom, 1989.

Nodel, Rabbi Julius. The Ties Between: A Century of Judaism on America’s Last Frontier. Portland, Ore.: Temple Beth Israel, 1959.

Toll, William. The Making of an Ethnic Middle Class. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1982.