Ashland, a city of 21,360 people in Jackson County, is situated in the Rogue River/Bear Creek Valley at the foot of the Siskiyou Mountains. The oak-studded foothills of the Cascade Range are clearly visible from the town's main thoroughfares, and Ashland's "Plaza"—the historic core of the downtown area—is adjacent to lower Ashland Creek, which runs through Lithia Park. Best known for its Oregon Shakespeare Festival, Ashland is also home to Southern Oregon University.

Established on the site of a Shasta Indian village, the city began as Ashland Mills, for Abel Helman's sawmill and flouring mill built on Mill (now Ashland) Creek. With fertile soils and extensive rangelands, the southern Bear Creek Valley's 1850s Donation Land Claim homesteads prospered.

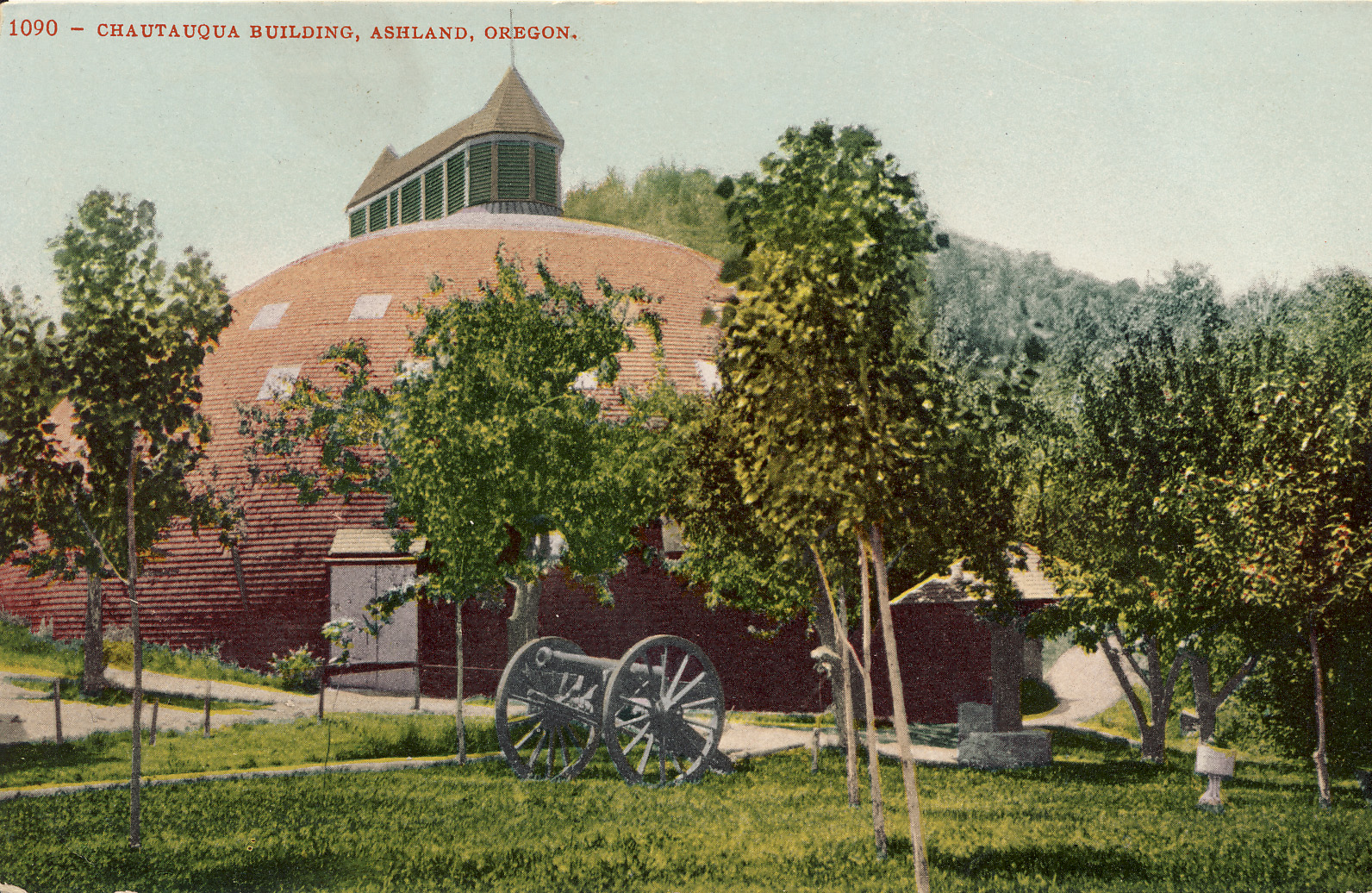

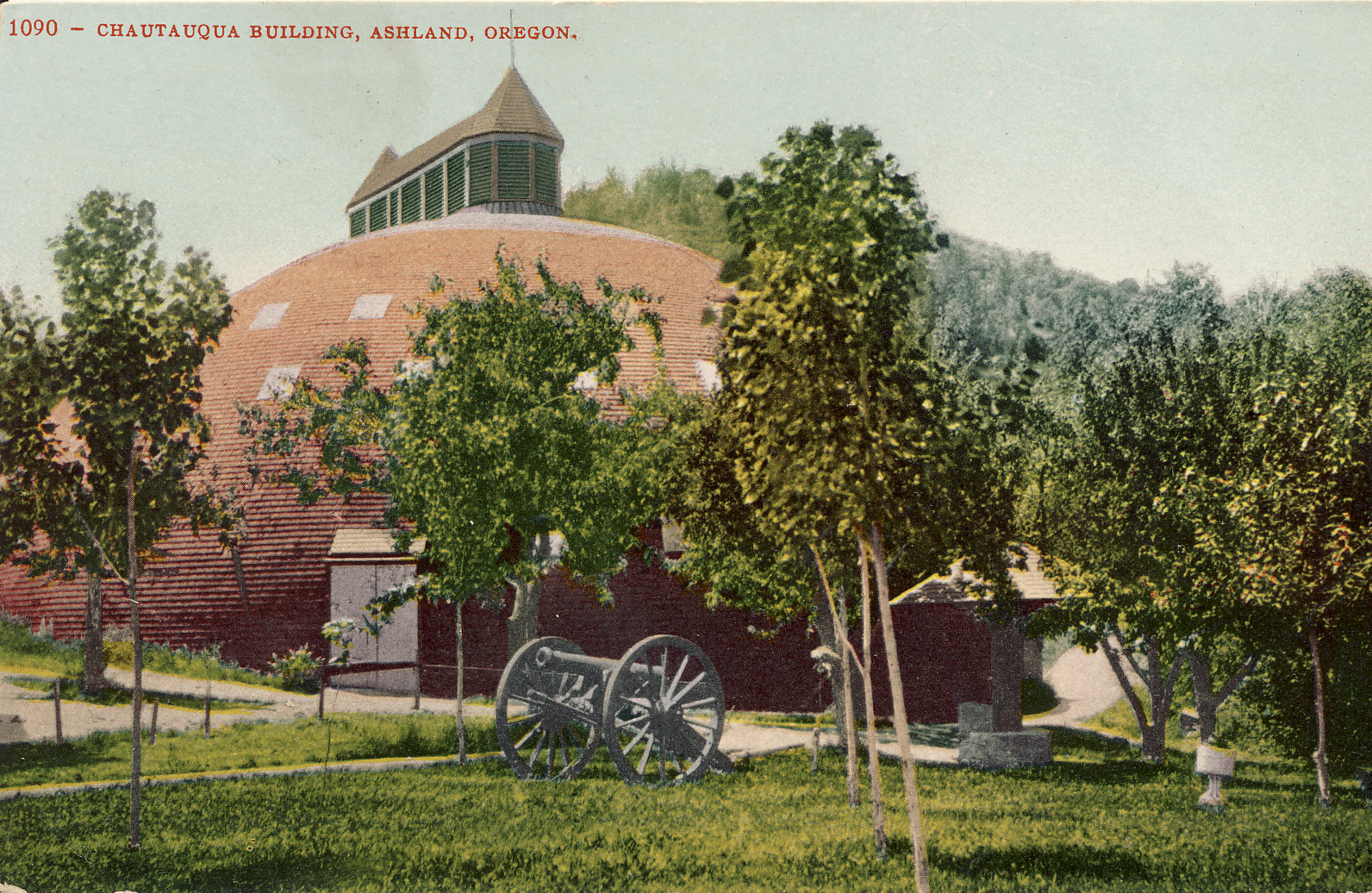

Ashland benefited from its location north of the formidable Siskiyou Pass, astride the route of the Oregon-California wagon trail, the stagecoach line, and in the 1880s the Southern Pacific Railroad, connecting Sacramento and Portland. Economically and politically, Ashland steadily eclipsed the county seat, the gold-mining boomtown of Jacksonville, and for a time became the largest and wealthiest community in southwestern Oregon. Beginning in the 1890s, Ashland secured its place as the region's cultural center by hosting southern Oregon's annual Chautauqua festival, held for two decades in a special beehive-shaped building overlooking what later became Lithia Park.

By 1910, however, the booming railroad and orchard town of Medford surpassed Ashland, and the town's leaders looked for new avenues to prosperity. With a largely homogenous population, Ashland's commercial club proudly advertised for new businesses by promoting the town as a comfortable haven for "American citizens . . . [one containing] no negroes or Japanese." Hopes that the area's "health-giving" mineral springs would draw tourists led to public and private investments, including the development of Lithia Park in 1914 and the construction of the Lithia Springs (now Ashland Springs) Hotel in the late 1920s. But a solid tourist boom failed to materialize.

When the Southern Pacific Railroad completed its "Natron Cut-off" over Willamette Pass to Eugene in 1927, most of Ashland's former rail traffic took this easier route. Employment and population began to drop, and soon the Great Depression brought even bleaker fortunes.

After World War II, Ashland regained a measure of prosperity with its small college and several sawmills that produced lumber for the postwar housing boom. The town's Shakespeare Festival, begun in 1935, grew steadily and became a catalyst for change in Ashland's fortunes. With the construction in 1970 of the Angus Bowmer indoor theater, the city began its dramatic shift to a tourism-dominated economy.

By the 1990s, Ashland had become a high-end tourist town. The city's simultaneous popularity as a retirement Mecca produced some of the highest property values in Oregon, as well as rampant gentrification and the steady exodus of many lower- and moderate-income residents. There was sustained, sometimes bitter conflict over new development and "growth vs. no-growth" city planning.

Despite the high cost of living, Ashland has become one of the most religiously (if not ethnically) diverse communities in the region. With its legacy of counter-culture eccentricities, its municipally owned services—hospital, utilities, cemeteries, and a fiber-optic cable network—and its liberal politics, the city is notably different from other towns in southwestern Oregon. Sneeringly referred to as the People's Republic of Ashland by some, the town often runs contrary to the region's prevailing political tide, voting down social-conservative initiatives that prevail elsewhere and passing tax levies for schools, libraries, and parks.

Ashland has gone against the regional grain for most of its history. Settled shortly before the Civil War by a small merchant class of midwestern Whigs and Republicans, Ashland stands in stark contrast to the rest of southwestern Oregon, which was dominated by gold miners and rural-minded "states rights" Democrats. Ashlanders voted for Lincoln in 1860, while the remainder of the region strongly supported the pro-slavery candidate, and the town remained a dependably Republican island in a Democratic sea for decades thereafter.

During the early 1900s, reforms such as women's suffrage and prohibition did well in Ashland but generally fared poorly elsewhere in southwestern Oregon. Decades later, in the 1990s, when much of southwestern Oregon sided with loggers and millworkers in the so-called Timber Wars (the spotted-owl controversy), it came as no surprise that Ashland stood alone and apart, a bastion of environmentalist activism.

-

![]()

Ashland Toll Road gate.

Photo Peter Britt, Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bc003900

-

![]()

Ashland Plaza, c. 1925.

Southern Oreg. Hist. Soc., SOHS01i_7647

-

![]()

Camping at Lithia Park, Ashland, 1911.

Southern Oreg. Hist. Soc., SOHS01i_2264

-

Ashland Mineral Springs Natatorium.

Southern Oreg. Hist. Soc., SOHS01i_5072

-

![]()

View from the veranda of The Hotel Oregon, Ashland.

Southern Oreg. Hist. Soc., SOHS01i_5894

-

![]()

Main St., Ashland, approaching the plaza area.

Southern Oreg. Hist. Soc., SOHS01i_152

-

![]()

Main St. looking southeast, Ashland, c. 1912.

Southern Oreg. Hist. Soc., SOHS01i_6639

-

![]()

Lithia Springs along Emigrant Creek on the outskirts of Ashland, c. 1915.

Southern Oreg. Hist. Soc., SOHS01i_9520

-

![]()

Holcom's flour mill on Ashland Creek, c. 1886.

Southern Oreg. Hist. Soc., SOHS01i_5132

-

![]()

Round house from railroad hotel bakery, Ashland.

Univ. of Oreg. Lib., Special Coll. and Univ. Archives, Randall V. Mills Photos, PH008_2458

-

![]()

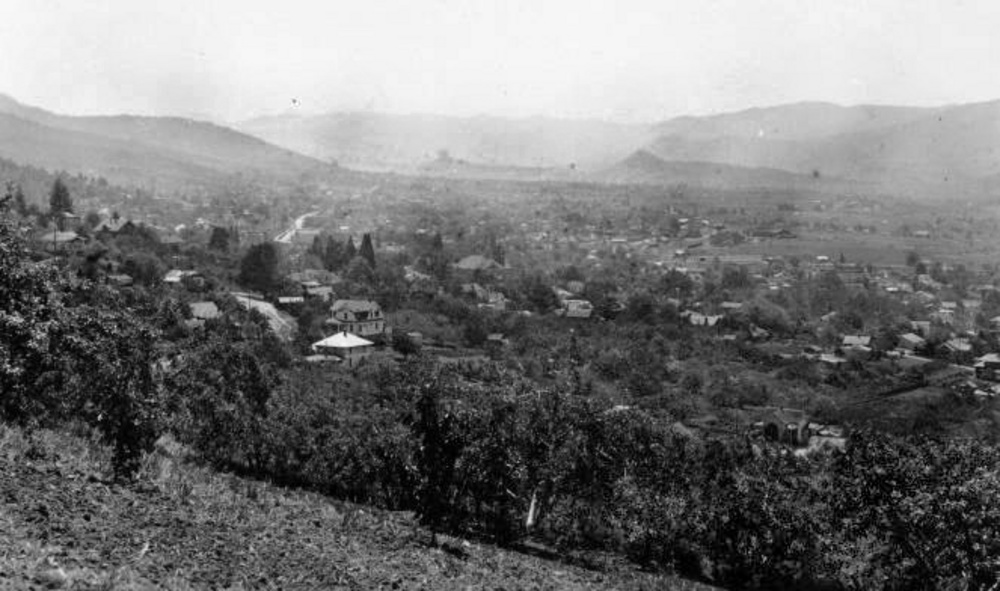

Ashland, 1935.

Oreg. State Univ. Archives, Walter S. Brown Photo Coll., P274

-

![]()

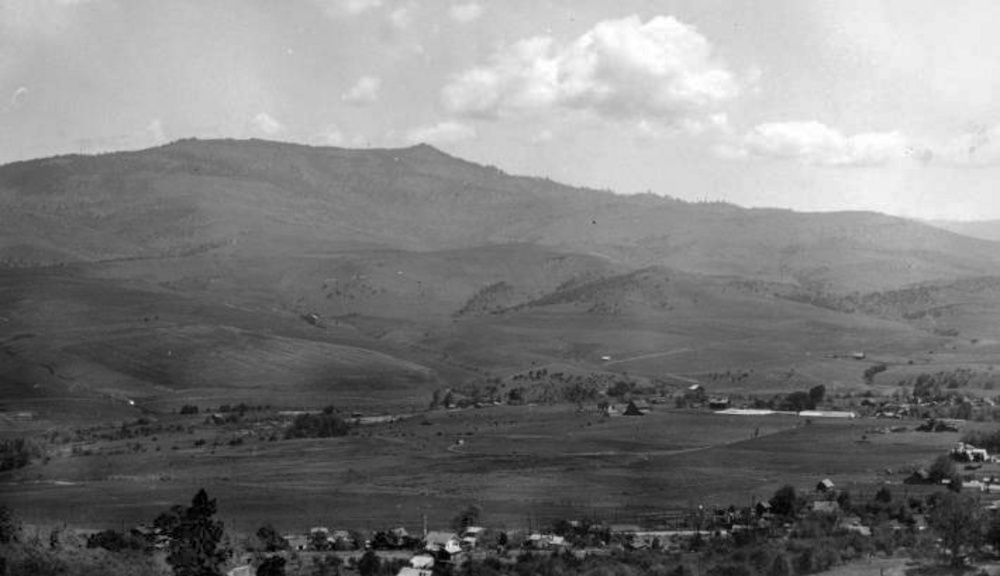

Grizzly Peak, from Ashland, 1935.

Oreg. State Univ. Archives, Walter S. Brown Photo Coll., P274

-

![]()

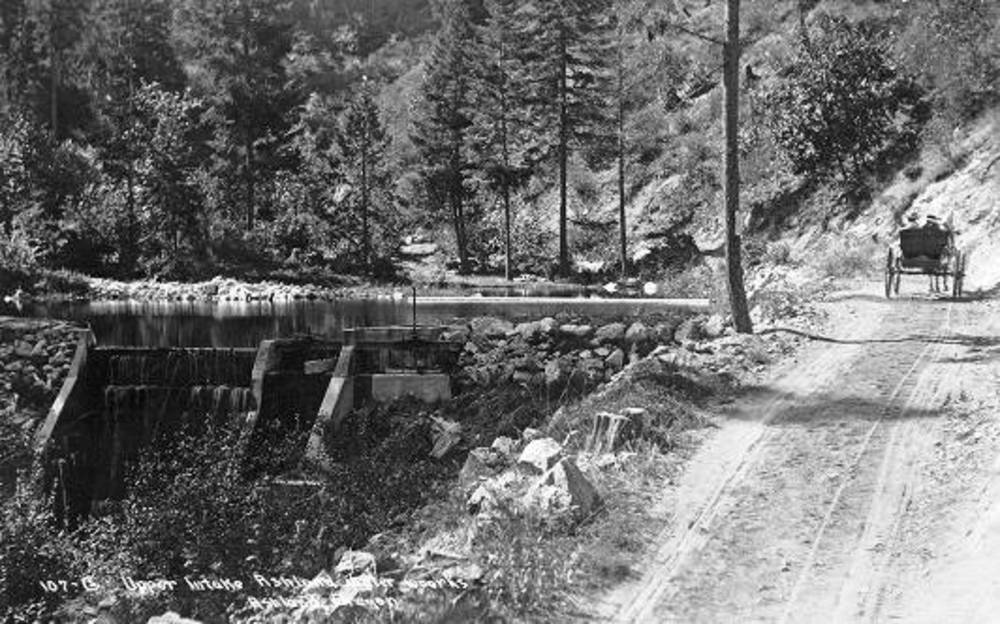

Upper intake, Ashland water works, 1915.

Oreg. State Univ. Archives, Gerald W. Williams Coll., Rogue River Valley album, WilliamsG:Rogue Ashland water

-

![]()

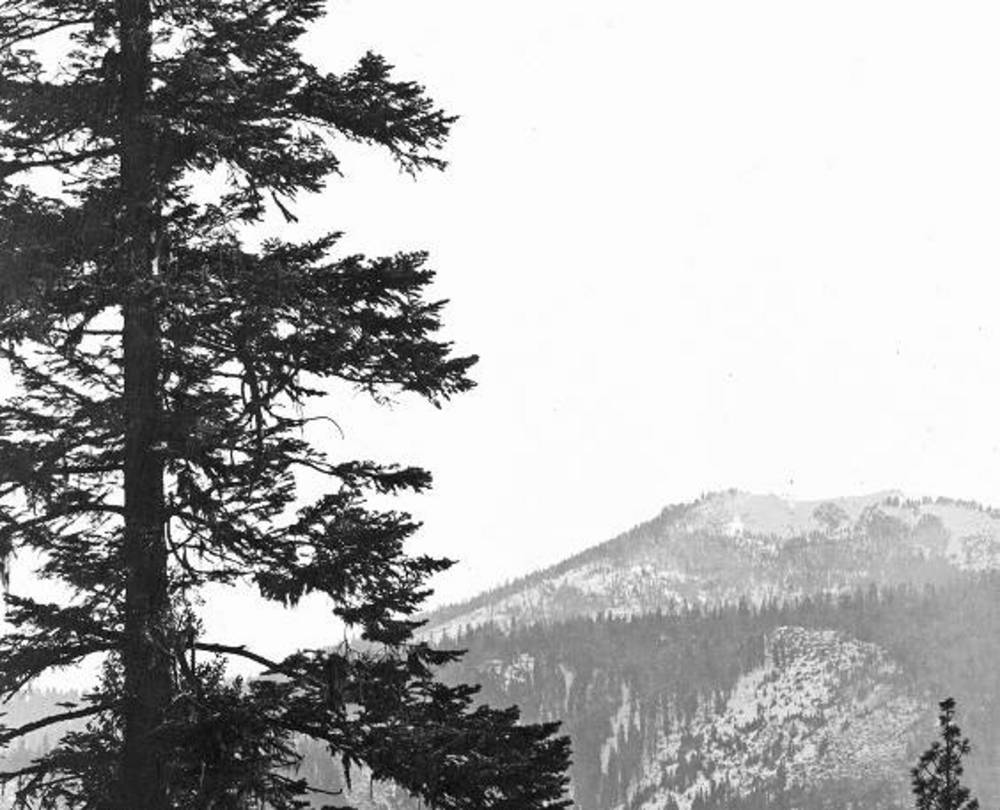

Mt. Ashland, 1915.

Oreg. State Univ. Archives, Gerald W. Williams Coll., Rogue River Valley album, WilliamsG:Rogue Mt Ashland

-

![]()

Downtown Ashland, 1925.

Oreg. State Univ. Archives, Gerald W. Williams Coll., Rogue River Valley album

-

![]()

Horticulture class at Ashland orchard, 1935.

Oreg. State Univ. Archives, Walter S. Brown Photo Coll., P274

-

![]()

Ku Klux Klan parade Ashland, 1910s or 1920s.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 49676

-

Varsity Theater during the Ashland Independent Film Festival, 2008.

Photo M. Wruck, courtesy Ashland Independent Film Festival

-

![]()

Postcard of the Chatauqua Building, Ashland, postcard, c. 1910.

Publisher Edward H. Mitchell, courtesy Robert L. Hamm

-

![]()

Ashland Creamery, ca 1897.

Southern Oreg. Hist. Soc., SOHS01i_94

-

![]()

Ashland depot and exhibit building.

Southern Oreg. Hist. Soc., SOHS01i_1623

Related Entries

-

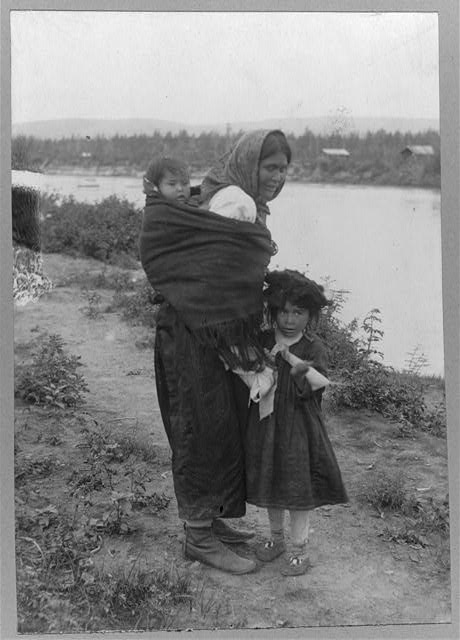

![Athapaskan Indians]()

Athapaskan Indians

According to Tolowa oral histories, the Athapaskan people of southern O…

-

![Bear Creek Valley]()

Bear Creek Valley

Oregon has over ninety separate streams named Bear Creek (far more, in …

-

![Chautauqua in Oregon]()

Chautauqua in Oregon

An 1874 summer camp to train Methodist Sunday school teachers seems an …

-

![Lithia Park]()

Lithia Park

Lithia Park in Ashland is a good example of what Fredrick Law Olmsted c…

-

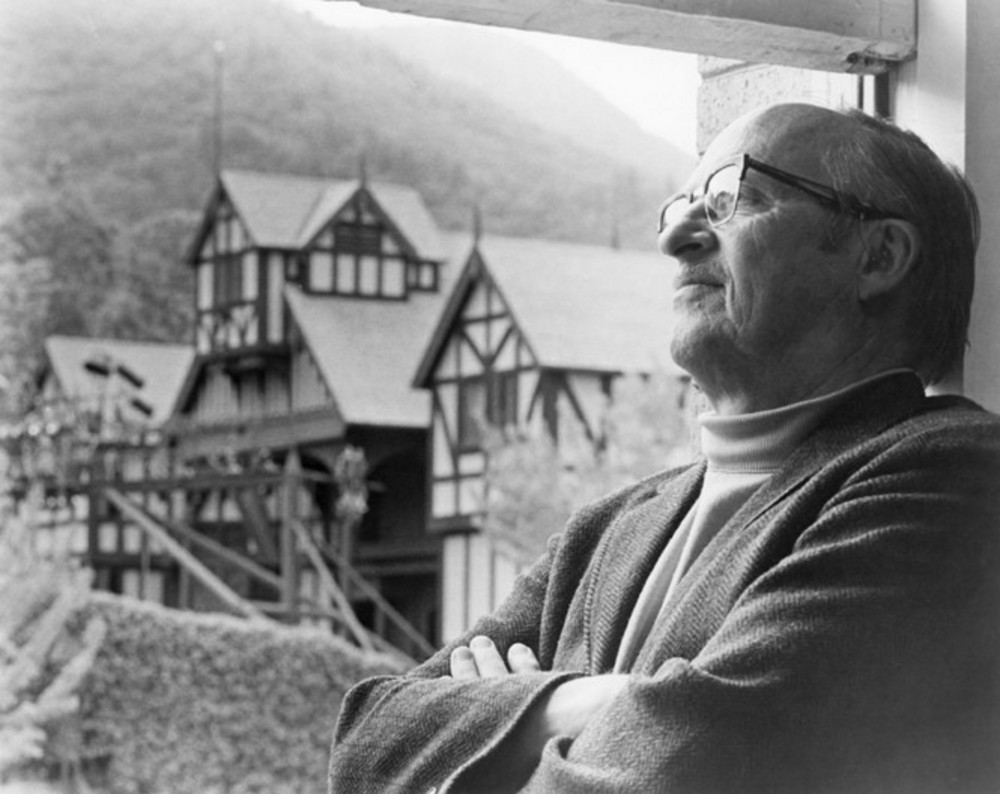

![Oregon Shakespeare Festival]()

Oregon Shakespeare Festival

The Oregon Shakespeare Festival (OSF), under the leadership of Angus L.…

-

![Southern Oregon University]()

Southern Oregon University

The origins of Southern Oregon University, situated on a leafy hillside…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Atwood, Kay. Mill Creek Journal: Ashland, Oregon, 1850-1860. Ashland, 1987.

O’Harra, Marjorie. Ashland in Transition: 1980s-1990s. Ashland:Ashland Daily Tidings, 2000.

O'Harra, Marjorie. Ashland: The First 130 Years. Ashland: Northwest Passags, 1986.