The Swedes were at one time one of the largest immigrant groups in Oregon. Between 1850 and 1940, only Canada and Germany had more immigrants to Oregon than the Swedes did. The majority of Swedes in Oregon settled west of the Cascade Mountains, most of them in urban areas, especially in Portland and the coastal cities of Astoria, Marshfield (Coos Bay), and North Bend.

Portland once had the largest population of Swedes in Oregon, most of them in northwest Portland, the Albina district, and Irvington. In 1910, over five thousand Swedish-born people lived in the city. Swedes could be found in almost every profession, including construction, engineering, medicine, business, and law. There were Swedish-owned hotels and restaurants, Swedish grocery stores and bookstores, a pharmacy, shoe stores and a hat shop, and in 1910 a Scandinavian American bank. Local Swedish contractors and laborers helped build the Ross Island, St. John’s, and Burnside bridges over the Willamette River. Swedes established Emanuel Hospital in Portland (now Legacy Emanuel Hospital) and Linnea Hall, built in 1909-1910 as the center of the Linnea Society in Portland. The First Immanuel Lutheran church still holds services in the building the Swedes built in 1905-1906. Swedes also lived in smaller Oregon communities, where they fished, logged, and farmed.

The Great Migration from Sweden

An estimated 1.2 million Swedes immigrated to America, the majority of them between 1840 and 1914, years when the Swedish population of Oregon was at its highest. The number of poor in Sweden grew throughout the nineteenth century, and a mass immigration to the United States started after a famine struck between 1867 and 1869. By 1910, 665,000 foreign-born Swedes lived in the United States, 10,099 of them in Oregon, compared to 4,555 in 1900 and 3,214 in 2015. Sweden experienced a population explosion around 1910, when five and a half million people lived in the country, an increase of 3 million since 1815. Three-quarters of the people in Sweden were farmers, and most were struggling. Many owned plots of land that were too small or had stony, unproductive soil, while others rented small farms from the nobility or government or worked as farmhands.

The majority of people who left Sweden for America during the nineteenth century were farmers who wanted to own land. Immigration increased dramatically after the Homestead Act of 1862 was passed, providing settlers with 160 acres of public land for a small filing fee with the requirement that they complete five years of continuous residence before receiving ownership. If a settler was willing to pay $1.25 an acre, he could obtain the land after six months. Other immigrants were in search of religious freedom. The Lutheran Church dominated religious life in Sweden during the nineteenth century, and citizens were required to belong to the church. Gathering in private homes for Bible study was prohibited, and Baptists, Methodists, and Mormons faced persecution.

Many Swedish immigrants who arrived in America at this time settled in the Midwest because farmland was available there and it had a climate and environment similar to Sweden’s. Once a Swedish community was established in America, others immigrated to join it, staying close to fellow Swedes who shared a language and customs.

By the early twentieth century, wages were increasing in Sweden, but there were periodic economic crises, often followed by waves of emigration. Between 1903 and 1906, some of the last Swedish settlements in the United States were established in places like Warren and Colton, Oregon. When the Depression struck in 1929, one in every ten foreign-born persons in Oregon was from Sweden, but Swedish emigration soon began to decline.

Oregon Immigration and Swedish Settlements

The 1850 census listed two foreign-born Swedes in the Oregon Territory; by 1860, there were fifty-six. In the following years, Swedes and other immigrants moved west in increasingly large numbers. In 1890, seven years after the completion of the transcontinental railway line to Portland, 3,774 Swedes lived in Oregon, an increase of almost 3,000 since 1880. Some of those immigrants had come directly from Sweden, but the majority came from other parts of the United States, primarily the Midwest.

A second wave of immigration to Oregon followed the 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland, which brought many visitors to the region who later returned to live there. The development of irrigation projects opened new land, which attracted immigrants who wanted to farm, and forest industries brought those who made a living in the woods or mills. Real estate companies advertised land in Swedish American newspapers such as the Oregon Posten. Most lived in Portland, but there were also small communities where only Swedes lived.

The first Swedish settlement in Oregon was Powell Valley, an agricultural colony east of present-day Gresham, between the Columbia and Clackamas Rivers. Powell Valley was originally resettled by the Powell family in the 1850s. The first Swede who settled there was Nils Fredrik Palmquist, who came to Oregon from Mariadahl, Kansas, in 1875. His brother, C. A. Palmquist, arrived in 1876, and more families from Kansas followed. People in Powell Valley were mostly farmers who grew hay, potatos, wheat, oats, and vegetables. Many planted orchards and grew apples, pears, plums, and cherries. It was the largest Swedish settlement in Oregon, with a school and three church groups, including a Lutheran church and the Missionary Friends.

Swedes also settled in Columbia County, especially in Warren on the Columbia River, twenty-five miles northwest of Portland and on the Northern Pacific Railroad line. One of the earliest Swedish settlers in the area was C. J. Larson from Kansas, who wanted to create a colony and advertised the town in the Oregon Posten. The advertisements worked, and Swedes in the Midwest began moving to Warren. Most of the forty Swedish-speaking families in and around the town belonged to the Lutheran congregation, which had a Sunday school, a youth organization, and a choir. The land was fertile, and immigrants worked in farming, dairy, fruit plantations, and lumber.

Other Swedish towns included Mayger, an old logging town between Portland and Astoria on the Columbia River that had been re-settled as a fishing and farming community by Finns and Swedes. There was also a Swedish American community in Carlton in Yamhill County, founded by John Wennerberg. In 1905, Reverend Carl J. Renhard, pastor at First Immanuel Lutheran Church in Portland and co-founder of Emanuel Hospital, established Carlsborg’s colony in present-day Colton in Clackamas County. He formed the American–Scandinavian Realty Company, purchased 1,960 acres of land, and offered Swedes the opportunity to purchase forty-acre farms. Swedes who settled in eastern Oregon were scattered throughout the area, where most were orchardists and wheat farmers. Only the northern part of Morrow County had enough Swedes to establish a Lutheran church.

Religious Life

Most Swedes in Oregon were Lutherans, but they also established Swedish Baptist, Methodist, and Mission Covenant churches. Most members of these churches were first- or second-generation immigrants who worshipped in Swedish until the 1930s, when many churches switched to English. Some churches offered classes in Swedish for American-born Swedes who did not speak the language. First Immanuel Lutheran Church on Northwest Irving Street in Portland continues to offer Christmas Morning Traditional Swedish Julotta, which is almost entirely in Swedish and features the Portland Lucia Court and Scandinavian Chorus.

Lutherans. Fifteen Lutheran congregations served Swedes in Oregon, and fourteen of them delivered services in Swedish. The first Swedish religious organization in Portland was the Swedish Evangelical Lutheran Immanuel congregation, organized in 1880. The original church building for the First Immanuel Lutheran church was completed in 1882 on West Tenth and Burnside; the current building at Northwest Nineteenth and Irving was constructed in 1905.

The first pastor of First Immanuel was Peter Carlson, who also founded the second Swedish church in Oregon, the First Lutheran of Astoria, in 1880. Carlson served until 1883, when Reverend John W. Skans succeeded him; Reverend C. J. Renhard, who helped start the Swedish Publishing and Printing Company, served the congregation from 1904 to 1910. By then, the church had purchased land in the Albina district east of the Willamette River with the intent of building a Swedish hospital. Renhard started another Swedish Lutheran congregation, Augustana, on Portland’s east side in 1906. The Swedish School of Portland is now housed in Augustana Lutheran Church and provides Swedish classes to children.

The Swedish Mission Friends. Svenska Missionsförsamlingen (The Swedish Mission Covenant Church), on NW Glisan Street, began holding services in Portland in 1887, and for many years the church was known as the Swedish Tabernacle. In 1938, the word "Swedish" was dropped from the name. Today, the Swedish Mission Covenant Church building, which is on the National Register of Historic Places, houses the McMenamins Mission Theater & Pub.

Swedish Organizations in Oregon

At the end of the nineteenth century, Swedish societies in Oregon helped connect immigrants to each other through social activities such as dances and picnics, and they also provided insurance and death benefits for their members. Many of these organizations still exist and work to preserve their Swedish heritage.

Swedish Society of Linnea. One of the most popular and oldest Swedish fraternal organizations in Oregon was the Swedish Society of Linnea, which derived from the sick-benefit organization, Svenska Bröderna (The Swedish Brothers), founded in 1888 by Philip W. Liljeson. At its peak, Svenska Bröderna had 150 members, all of them male and most of them bachelors, but the number of members changed as politics and the labor market fluctuated. In 1892, because of low membership numbers, the Society welcomed women as members and changed its name to Svenska Sällskapet Linnea (Swedish Society of Linnea) after botanist Carl von Linné. By 1910, the organization had about 300 members, with equal numbers of women and men. In 2020, the organization had about 40 members.

Linnea’s purpose was to “help and steady the weak and faltering; to aid its members to grow both intellectually and morally; to nourish a sense of the rich national heritage of Sweden, and to protect the Swedish language.” Membership dues in 1910 were three dollars, with a monthly charge of 50 cents. In return, the Society helped members pay for hospitalization and funeral expenses. Having insurance was especially important if you did not have a family, and it was a great relief knowing that assistance was available.

The Linnea Hall, designed in Scandinavian Baroque Revival style, was built at 666 (today 2066) Northwest Irving Street in Portland. The hall was sold in 1979 and is on the National Register of Historical Places. Linnea continues to serve the immigrant community as a social club and charity organization for the Swedish immigrant population. Other Swedish organizations include the Vasa Lodges, the New Sweden Cultural Heritage Society, and the Scandinavian Heritage Foundation.

Court Scandia #7, Foresters of America. Court Scandia #7, Foresters of America was established on February 1, 1892, as a local chapter of the Order of Foresters, and met into the 1930s. Organized by forester C. W. Helmer, Court Scandia #7 began with only fifteen members but claimed 269 members by 1910. The Order of Foresters was a sick-benefit organization, and Court Scandia #7 paid out more than $1,600 a year in illness benefits and other charities. Both Court Scandia and Linnea had a Swedish library.

Vasa Order of America. The Vasaorder (now called the Vasa Order of America) was the largest Swedish organization in America, with more than 300 lodges and 40,000 members in 1915. The Portland chapter, Logen Nobel #184, had 200 members in 1915. The organization was started as a benefit fraternal society in several locations in Oregon. It is still active.

Swedish choral societies. Singing is a large part of Swedish culture, and Swedish choral societies formed in towns all along the Pacific Coast. Svenska Sångarförbundet på Stilla Havskusten, the Swedish choral society of the Pacific Coast, was founded in 1905 and had about a dozen choral societies by 1910. Astoria had a men’s chorus, and Colton had an Oratorio Society. Columbia, a male choir, was founded in Portland in 1903 with 25 members; its first concert was on February 4, 1904. The Portland Nordic Chorus performs songs in Swedish, as well as other Nordic languages.

Newspapers

The largest Swedish language newspaper in Portland was Oregon Posten, published by Fredrik Wilhelm Lönegren from 1908 to 1936. The weekly paper covered news and events and also printed novels, poems, and short stories. The paper announced Swedish events, carried church news, and published information about who sold Swedish food. The paper also published information about Oregon, aimed at people interested in moving to the state.

The Decline

World War I was a turning point for Swedish American communities in the United States. Immigrants, especially Germans but also Swedes, were persecuted, causing them to change some of their behavior and attitudes, and many turned away from Swedish institutions and traditions. Speaking in a foreign language was discouraged. Many churches delivered sermons in English, and Swedish church congregations grew smaller.

Immigration from Sweden continued to decline as economic opportunities and living standards improved in Sweden and conditions worsened for immigrants during the Great Depression and World War II. The 1930 census found 11,032 Swedish-born residents in Oregon; by 1950, that number had decreased to 6,904. As the first generation of Swedish immigrants died, so did the language in Oregon. Swedes began to marry outside their communities and embrace American traditions.

In the twenty-first century, there are thousands of people in Oregon who have Swedish heritage. Swedish organizations in Portland include the Vasa Order of America, Linnea, New Sweden Cultural Heritage Society, the Scandinavian Heritage Foundation, Norida House, and the Swedish School. There are still Swedish midsummer celebrations in the state, and a Scandinavian festival is held in Portland each year at Christmas.

Prominent Swedes in Oregon

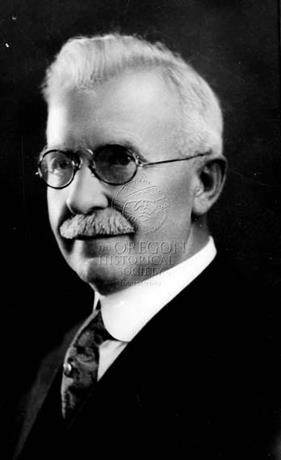

John Andrew Bexell (1867-1938) was dean of the School of Commerce at the Oregon Agricultural College (now Oregon State University) from 1908 to 1932. Bexell Hall is named after him.

Karl P. Billner (1882–1965) designed several bridges for the Historic Columbia River Highway, including Benson Bridge, Bridal Veil Creek Bridge, Crown Point Viaduct, and Latourell Creek Bridge.

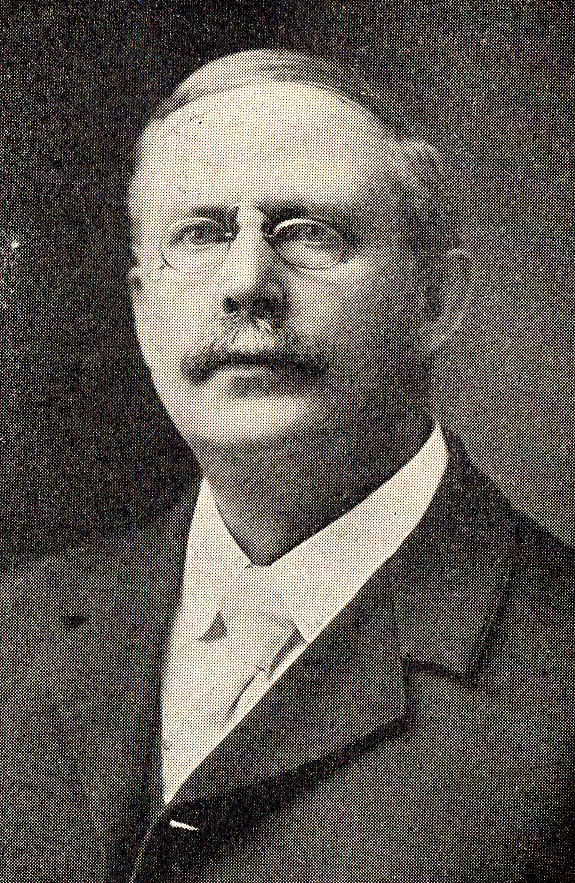

John Helmer (1886–1970) opened a haberdashery, John Helmer’s The Man Shop, on Southwest Washington Street in Portland in 1921. By 1927, he had moved the shop to its current location on Southwest Broadway. The store is currently operated by his grandson.

Martin William Hawkins (1888–1959) was a track star at the University of Oregon. He placed third in the 120-yard hurdles at the Stockholm Olympics in 1912, tied the world record of 15.2 seconds in his specialty twice, and was Oregon’s top point-scorer for three years. A lawyer and judge, he was the head track coach at the University of Oregon for forty-three years and was inducted into the University of Oregon Athletics Hall of Fame in 1997.

Gustaf (Gustave) Bernhardt Hegardt (1859–1942) was an engineer from Västergötland. He helped build the jetties at the mouth of the Columbia River and was chief engineer and secretary for the Portland Dock Commission.

The firm of Lindstrom & Feigenson was a Portland bridge contracting firm that built St. Johns Bridge, Ross Island Bridge, John McLoughlin Memorial Bridge, and Lewis & Clark Bridge. The vice presidents of the company were Oscar J. Lindstrom and Anton J. Lindstrom, who had immigrated to the United States in the early 1900s.

Fredrick W. Lönegren (1860–1937) had strong opinions about the importance of keeping Swedish heritage alive. He promoted Swedish culture and language through Oregon Posten, a newspaper that often advertised Oregon as a place to settle.

Albin Walter Norblad (1881–1960), born in Malmo, practiced law in Astoria, where he was city attorney. He served two terms in the State Senate and was president of the Senate in 1929. When Governor Isaac L. Patterson died in office, Norblad succeeded to the governorship and served the remainder of his term.

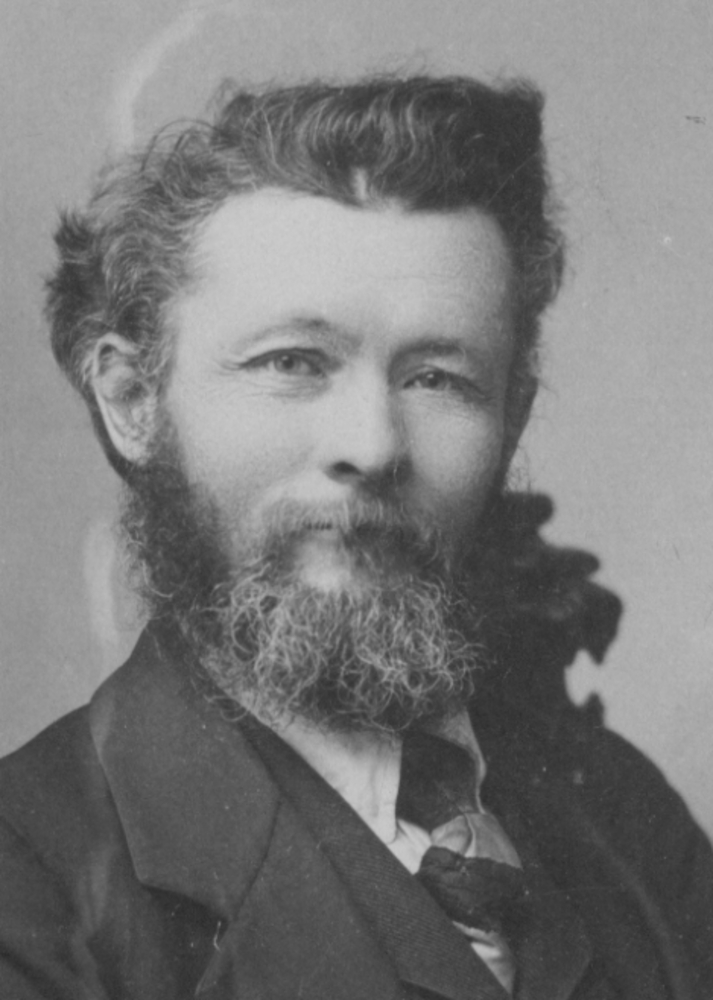

Ernst Skarstedt (1857–1929), born in Bohuslän, was an author and newspaper publisher. In 1889, he published the first book in Swedish in Oregon, a biography and tribute to his deceased wife Anna. He published a newspaper, Demokraten (The Democrat), Oregon och Washington: Dessa staters historia, resurser och folkliv (Oregon and Washington: The History, Resources and Folklore of These States), and Oregon och dess svenska befolkning (Oregon and its Swedish Population).

May and Ann Shogren (May, 1861–1928; Ann, 1868–1934) were daughters of Swedish immigrants who opened a haute couture dressmaking shop at Southwest Tenth and Yamhill in the mid-1890s. M & A Shogren was Oregon’s most significant fashion house for over twenty years, employing as many as a hundred women from 1900 to 1910. Many of their dresses can be found in the museum collections of the Oregon Historical Society.

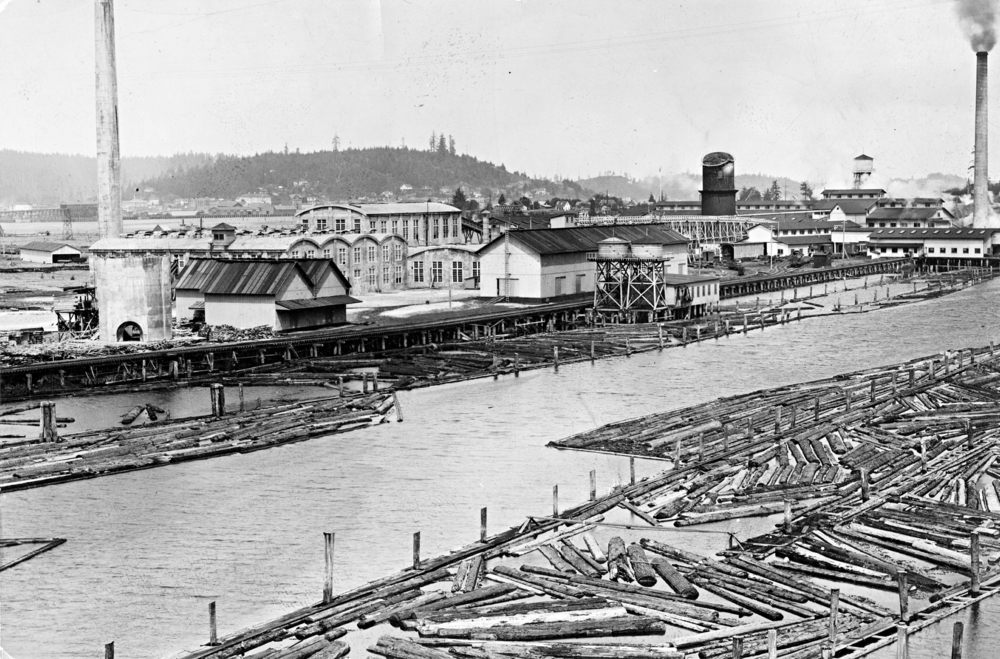

Charles Axel Smith (1852–1925), born in Östergötland, was one of the state’s leading lumberman and the owner of C.A. Smith Company. He operated seventy-one logging camps near Coos Bay and operated the area’s largest sawmill in Marshfield. By 1920 about half the loggers and sawmill workers on Coos Bay worked for him.

-

![]()

-

![]()

Swedish women vying for the crown at the Swedish Midsummer Festival, Viking Park, Portland, June 1940.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., Journal Coll., 011674

-

![]()

Cast photo, Swedish American Dramatic Society of Portland, 1907.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., 022213

-

![]()

Beech Street Swedish Methodist Episcopal Church, c.1930.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., Oregon Journal, 371N5372

-

![]()

First Swedish Lutheran Church, Astoria.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., Orhi24892

-

![]()

Swedish Tabernacle Mission Church, Portland.

Courtesy Angelus Studio photographs, 1880s-1940s, University of Oregon. "PH037_b181_73415" Oregon Digital -

![]()

Oregon Posten, ads in the Praktupplagan issue, June 1, 1910.

Courtesy Minnesota Historical Society, Swedish American Newspapers project -

Skarstedt, Ernst.

Ernst Skarstedt.

-

![]()

J. A. Bexell, 1922.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., 000870

-

![]()

John Helmer, 1994.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., SR3009

-

![C.A. Smith Lumber Co., Coos Bay]()

C.A. Smith Lumber Co., Coos Bay.

C.A. Smith Lumber Co., Coos Bay Oregon Historical Society Research Library OrHi 8291

Related Entries

-

![C.A. Smith Lumber Company]()

C.A. Smith Lumber Company

Charles Axel Smith became, for a time, one of Oregon's most powerful lu…

-

Ernst Skarstedt (1857-1929)

Ernst Teofil Skarstedt was the first author and newspaper publisher to …

-

![Fredrik Wilhelm Lönegren (1860-1937)]()

Fredrik Wilhelm Lönegren (1860-1937)

Fredrik Wilhelm Lönegren moved to Portland on October 3, 1908, to start…

-

![M & A Shogren]()

M & A Shogren

The dressmaking business of M & A Shogren was Portland’s haute coutu…

-

![Oregon Posten]()

Oregon Posten

The first issue of the weekly Oregon Posten (Oregon Post), the state’s …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Lönegren, F.W. Oregon Posten. Portland, Ore.: Swedish Pub. & Print. Co, December 2, 1908 - January 23, 1936.

“Swedish Lodge Beautifies Northwest Irving.” Northwest Examiner, October 1988.

Barton, Arnold H. A Folk Divided: Homeland Swedes and Swedish Americans, 1840-1940. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1994.

Barton, Arnold H. Letters From The Promised Land, Swedes In America, 1840-1914. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1980.

Capps, Finis H. From Isolationism to Involvement: The Swedish Immigrant Press in America, 1914-1945. Chicago: Swedish Pioneer Historical Society, 1966.

Handlin, Oscar. The Uprooted. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1951.

Passi, Michael, and Larry Skoog. Peoples of Oregon [sound recording]. Northwest Institute of Ethnic Studies, Oregon Historical Society, 1971-72.

Smith, William Carlson. The Swedes of Oregon. Philadelphia, PA: American Swedish Historical Museum Year Book, 1946.

"Ernst Skarstedt's Oregon-Swedish Biographies." Swedish Roots in Oregon. http://www.swedishrootsinoregon.org/Publications/Skarstedt_Biographies.html

Vincent, John. "John Helmer: Mad Men Style." Business Tribune, August 11, 2015. http://publications.pmgnews.com/epubs/portland-tribune-business-081115.pdf

"Gov. Albin Walter Norblad." National Governors Association. https://www.nga.org/governor/albin-walter-norblad/