Immigrants from the West

Resting in the shade of the Gresham Pioneer Cemetery, there is a grave marker with the name Miyo Iwakoshi. The name is not widely known in Oregon, but it is historically significant since Iwakoshi was the matriarch of the first Japanese family to settle in the state. Her arrival in 1880 spawned the immigration of thousands of people from Japan who would contribute to the state's economic development as they struggled against discrimination and tested America's civil rights. Iwakoshi arrived with her Scotsman husband, Andrew McKinnon, and their five-year-old adopted daughter, Tama Nitobe. Oregon was growing rapidly at the time, and McKinnon built a steam sawmill called Orient. The community of Orient still exists near Gresham.

Since the 1850s, laborers from China had arrived in Oregon to work primarily on the railroads. They lived in crowded quarters, spoke a language that was unfamiliar to most Americans, and did not assimilate readily. To appease West Coast working-class resentment against the cheap labor and what many considered the racial impurity of Chinese laborers, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. The immigration of labor from China came to a halt. Still, workers were needed, so the labor market in Japan was exploited.

Japantown

In Oregon, labor contractors arranged for workers to come through Portland before going to their work assignments in eastern Oregon, Idaho, and points beyond. As hundreds of immigrants arrived in Portland, a Japantown (Nihonmachi) formed in the Old Town area between Northwest Second and Sixth Avenues. There were demands for hotels, restaurants, bathhouses, barbershops, and other services. Because new arrivals spoke only Japanese, entrepreneurs were usually immigrant Japanese. Japantown existed in Portland from 1890 through 1942.

Japantown was predominantly composed of young bachelors. Although many wanted to simply work hard and earn money to send home, others were drawn into the easier life of drinking, gambling, and having a noisy good time. In 1893, the Rev. Sadakichi Kawabe established the Portland Japanese Methodist Church, with prominent members of the community participating in a campaign to rid the community of its vices. This church continues today as the Epworth United Methodist Church.

The first Buddhist priest arrived in 1903. The Rev. Shozui Wakabayashi established a church and dormitory and offered assistance to meet the spiritual and social needs of the community. He began an early outreach program, visiting logging and farm camps to spread his teachings. In eight years, there were 570 parishioners. This church continues today as the Oregon Buddhist Temple.

Thousands of Japanese laborers obtained jobs and gained help with their working needs and travel arrangements from labor contractors. Among those, Shinzaburo Ban, who also ran a mercantile store on Northwest Third and Couch in Portland, was the most prominent. By 1910, many of the 3,418 Japanese immigrants, or Issei, in Oregon had fulfilled their contracts and were no longer the young bachelors who had arrived ten or fifteen years earlier. Their original intentions to work in America for a few years, become rich, then return to Japan, had faded. Many decided to stay in America, but they needed wives to raise families.

Families

Because the 1922 Cable Act punished citizens for marrying aliens, the Japanese men who had enough savings returned to Japan to seek wives. Others who could not afford the expense sent flattering photos of themselves to family members. In return, families sent photos of prospective brides. A real incentive for these "picture brides" was the realization that there would be no mothers-in-law in America. After the 1907-1908 Gentlemen's Agreement between Japan and the United States allowed family members to immigrate, the number of Issei women in Oregon increased from 294 in 1910 to 1,349 in 1920.

In Portland, families moved into various parts of the city and started grocery stores, barber shops, and hotels, but the core of Japanese businesses remained in Japantown. There, business transactions and social contacts could be conducted in Japanese and among friends, and many families lived in the rear of their businesses. Japantown grew, with more than a hundred Japanese businesses and offices, including Teikoku and Furuya grocers, Ota Tofu, S. Ban Mercantile, the Royal Palm Hotel, Kobayashi express company, Yabuki Laundry, Oshu Nippo newspaper, Tokio Sukiyaki restaurant, and dentists Dr. Kei Koyama and Dr. Kiyofusa Katayama. Portland's Japanese population increased from 20 in 1890 to 1,460 in 1910.

By the 1920s, the demographics changed considerably with the birth of large numbers of Nisei, the second generation. Children of Japanese and Chinese families living in Old Town attended Atkinson School, a dilapidated, wooden building located near Northwest Eleventh and Davis Streets. Japanese students living in Southwest Portland attended Shattuck School. High school students living on the west side attended Lincoln High School, now a building on the Portland State University campus.

By the time students attended public schools, the communication among Nisei students and between parents and children was often a mixture of Japanese and English. Because most students attended Japanese school after regular school each day, few had time to participate in extracurricular programs. Two Japanese schools operated in Portland: North School, at Northwest Fifth and Flanders, and South School on Southwest First and Mill Streets. Other Japanese schools were located wherever there were concentrations of Japanese families, including Milwaukie, Hood River, Gresham, Banks, and Salem. The curriculum consisted of reading, writing, and speaking Japanese. Japanese calligraphy was taught on Saturday mornings.

Agriculture

Japanese agricultural communities developed in rural areas. By 1909, after many invested their earnings as migrant laborers, more than one-quarter of the 3,873 Oregon Issei were involved in farm labor. In east Multnomah County, they raised berries and vegetables. Hood River, where Issei received marginal property (stumpland and marshland) in exchange for clearing land, had the second largest settlement. There, Issei grew berries and asparagus as quick cash crops between their apple and pear seedlings. North of Salem in Lake Labish, Issei produced Golden Plume Celery, developed by local grower Roy Fukuda. From 1907 to 1910, the number of Japanese farmers increased from 71 to 233.

The increased number and success of Issei farms brought fears of Japanese competition. In 1919, an Anti-Asiatic Association formed in Hood River, pledging not to sell or lease land to Japanese. That year "Potato King" George Shima purchased land near Redmond and hired Japanese potato experts to raise seeds for his California farms. The county farm bureau stood against his project and forced him to withdraw.

By 1923, about 60 percent of Oregon's Japanese population was involved in agriculture. That year, after three unsuccessful bills, the Oregon legislature passed the Alien Land Law, which prohibited Issei from owning or leasing land. There was a loophole in the law, however, that allowed Issei to buy land in the name of their American citizen children. A year later, Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924, prohibiting aliens who were ineligible for citizenship from entering the United States altogether.

By 1940, the older Nisei were in their early 20s. Many had gone on to universities, but job prospects for them were dismal, and, following graduation, many returned to work on their family farms or grocery stores. Issei continued as the elders and as community and family leaders in the Japanese community.

Executive Order 9066

Nineteen forty-one was the year that changed the lives of almost all persons of Japanese ancestry living in the United States. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor and the U.S. declaration of war on December 7, 1941, prejudice grew against anything or anyone Japanese. Many Caucasian farmers organized to rid successful Japanese of their farms. The Ku Klux Klan, the American Legion, and other "patriotic" groups wanted to deport all Japanese. One major obstacle stood in the way. Seventy percent of the 120,000 persons who would be affected by an evacuation program were American citizens and, technically, protected by the Bill of Rights.

To skirt this issue, pressure was brought on President Roosevelt to sign Executive Order 9066. The order, signed on February 19, 1942, gave Lt. Gen. John DeWitt, commander of the Western Defense Command, authority to designate areas as strategic for military purposes and to exclude anyone he chose from those zones. DeWitt designated a zone approximately 200 miles wide along the West Coast and ordered the removal of all persons of Japanese ancestry. To justify his position, he publicly made the statement that "a Jap is a Jap."

In Portland, the exclusion order issued on April 28, 1942, required all Portland residents to report by May 5 to the assembly center in North Portland. Other orders followed around the state, with those from Hood River and Marion counties sent to Pinedale in northern California. Because people could only take what they could carry, families had to dispose of their businesses, furniture, and personal possessions. They had no idea where they were going or when they would return. It was a time of doubt, fear, and confusion.

Portland Assembly Center

The Portland Assembly Center had previously been used as stockyards, and the dirt ground that normally housed livestock was covered with a plank floor. Cubicles with eight-foot walls housed families, with space only large enough to accommodate family members' cots. Privacy was almost nonexistent. Night noises from adjoining cubicles could easily be heard over and through the thin walls.

The assembly center housed about 3,500 people. A board of leaders organized a small city within the center and set up a post office, security department, fire brigade, mess hall, and publishing office, along with recreational and educational activities. Residents ate meals in two shifts, served family style for maximum efficiency. Workers washed dishes quickly via an assembly line. For recreation, young people held dances, viewed movies once a week, and checked out sports equipment and games. Issei were generally bored, but eventually women's groups organized English and craft classes. There were church services conducted for various religions and denominations on Sundays. Despite these activities, the barbed wire and armed guards were a constant reminder that the civil rights of those of Japanese ancestry were being denied.

A number of exceptional incidents occurred in the Portland Assembly Center during its four months of existence. Dysentery broke out and there was a desperate rush to use the limited toilets. One can imagine the agony and desperation suffered by those afflicted. One day, a Military Police cook came through the gate to borrow food items from the center's kitchen. A Military Police guard shot him in broad daylight-a sobering sight for the internees. The incident that everyone remembered later occurred on a hot day in the spring of 1942, when the Center resembled an oven. The fire department came up with a solution. They would hose down the hallways and, as the water evaporated, the surfaces would cool down. It was a good idea, but they forgot one variable. As the halls were doused, water seeped through the plank floors and moistened the dirt and manure mixture underneath. The result was stench and hordes of flies. For days, thousands of flypaper rolls hung throughout the Center.

Life in the Camps

By early September, the ten "permanent" concentration camps were completed, built in desolate desert areas in several western states. With the autumn leaves turning color, the Portland contingent was moved by train to the Minidoka camp near Twin Falls, Idaho, and Oregonians from Pinedale transferred to Tule Lake in northern California. All of the camps consisted of hundreds of tarpaper barracks, guard towers, and barbed wire fences.

The barracks were approximately 20 feet by 100 feet and sectioned into five or six one-room "apartments." With only what they could carry, family members stepped into rooms that were bare except for an army cot and a mattress for each person, a potbellied stove, and a single light bulb. From huge piles of scrap lumber, residents built chairs, tables, screens, and other items. For those who could not build for themselves, volunteers were happy to help. Later, many men carved art objects using scrap lumber and desert plants.

Camp life confirms that humans are adaptable. Issei and Nisei learned to live without running water, privacy, or electrical outlets. They adjusted to walking 40 or 50 yards to wash or shower and learned to tolerate an apartment covered with dust from windstorms. During cold winter months, it was a simple matter to create skating ponds. The coal-burning, potbellied stoves glowed red, and fire was a constant concern.

Life in camp was more difficult for the older Issei who were accustomed to working ten or twelve hours a day on their farms or managing hotels or grocery stores. In the camps, they had to adjust to boredom. Young people had no difficulty organizing sports programs, planning dances, or playing cards. As those activities went on, the family structure slowly disintegrated. Family members spent most of the day and evening with friends and seldom were together to share experiences and thoughts. They even ate meals separately.

The Military

Nineteen forty-three was the year of turmoil and upheaval. More than 3,000 West Coast Nisei were serving in the military service before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Following December 7, 1941, those Nisei who had 1A classifications and who were ready to be inducted were reclassified to 4C, "enemy aliens." During the spring of 1943, authorities reversed their decision. They inducted Nisei into military service and encouraged as many internees as possible to relocate to eastern cities.

To carry out this program, they devised a questionnaire to separate the "loyal" from the "disloyal." The critical questions were so ambiguous that confusion and anger resulted. About ten percent of internees from the ten camps, classified as "disloyal," were segregated at the Tule Lake camp. The "loyal" Nisei and Issei were allowed to apply for work or education leaves or to volunteer or be drafted into the army. Japanese on the Hawaiian Islands were largely excluded from internment, with fewer than 2,000 of the 158,000 sent to concentration camps.

Thus, two major all-Nisei military units were formed. Around 4,500 served in the Military Intelligence Service (MIS) after studying Japanese language at Fort Snelling, Minnesota. The MIS became "America's secret weapon" in the South Pacific, for they eavesdropped behind enemy lines, translated Japanese documents, and interrogated prisoners of war. Eighteen thousand from Hawaii and the mainland trained for the 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT) at Camp Shelby, Mississippi. The 442nd RCT saw combat in Italy and France and became the most decorated unit in the history of the United States Army for its size and length of service. It also suffered the highest combat casualty rate of any unit that served.

One group of Japanese Americans who refused to serve in the United States military were classified as "no-no" boys. Some were opposed to the United States. Others were angry at the treatment of Japanese Americans and offered to serve only if their families were given their freedom. Their requests were not granted, and they were sentenced to prison, not to be released until after the war.

Resettlement

As the war continued, the majority of Japanese Americans remained in the camps, primarily because they no longer had homes or businesses. In 1944, Californian Mitsuye Endow successfully challenged the constitutionality of E.O. 9066 before the U.S. Supreme Court. Finally, in 1945, the camps closed.

Many families decided to start new lives in eastern locations. Almost 69 percent of Japanese Americans in Oregon returned to their former hometowns, but they often faced campaigns to exclude them from their communities. In Gresham, the Japanese Exclusion League held rallies for a law that would deny citizenship to those of Japanese descent. Hood River gained national notoriety when the local American Legion post removed the names of sixteen Nisei servicemen from a public honor roll and sponsored full-page newspaper ads warning "Japs are not wanted in Hood River."

The period of resettlement after the war was significant in that Japanese Americans assimilated throughout the country. The English-speaking Nisei were starting their own families. Culturally, they were more American than the Issei and had more options choosing their life goals. In Portland, there was no longer a Japantown. Rice, sake, soy sauce, and other Japanese products were becoming available at the Safeway and Fred Meyer stores. Eventually, the third and fourth generations of young people appeared, and most of their friends were Caucasians.

New Generations

As the fourth and fifth generations of Japanese Americans have come of age, they socialize within the larger population. Intermarriage has become the norm, with 31 percent of Japanese Americans in 2000 identifying themselves as multi-racial. People who do not necessarily look Japanese have Japanese names. They seem to be part of the "multicultural" world that is emerging in these times.

In 2000, 85 percent of those with Japanese ancestry in Oregon lived in just eight counties: Multnomah, Washington, Clackamas, Lane, Marion, Jackson, Benton, and Malheur. The population of Malheur County is distinctive, having the highest percentage of Japanese Americans (still less than two percent of its population) and, among those, the lowest percent who are biracial, at 16 percent.

-

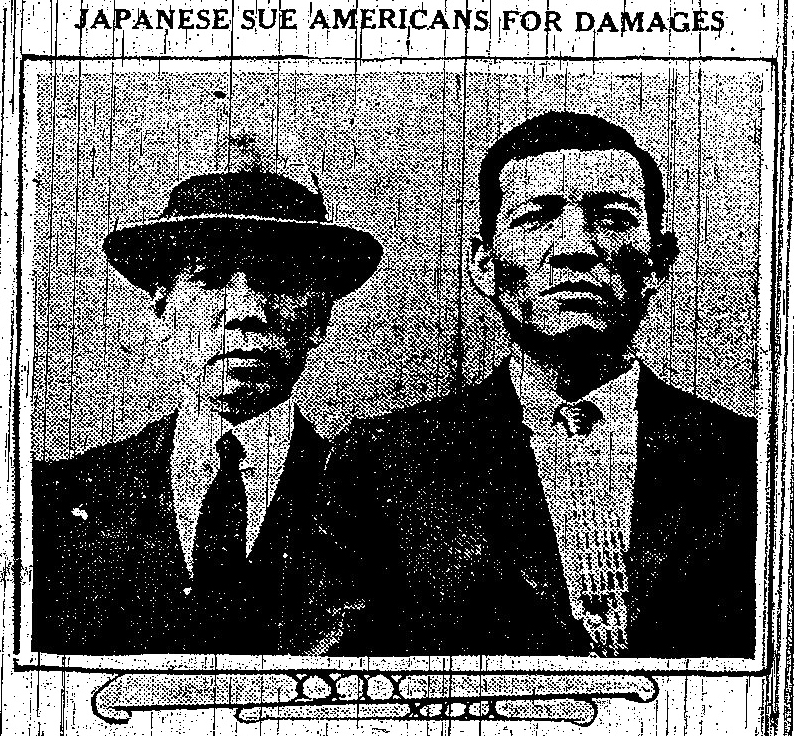

![Shinzaburo Ban.]()

Ban, Shinzaburo, ba019614.

Shinzaburo Ban. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., ba019614

-

![]()

Yaeko Kiyohiro with an Ikebana design at the Japanese Doll and Peach Blossom Festival, Portland, 1940.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Journal, 011983

-

![Family Merchant Hotel (ONLC). Japanese laundry at Family Merchant Hotel, currently the Oregon Nikkei Legacy Center.]()

Family Merchant Hotel.

Family Merchant Hotel (ONLC). Japanese laundry at Family Merchant Hotel, currently the Oregon Nikkei Legacy Center. Courtesy Oregon Nikkei Legacy Center

-

![Frank Hachiya]()

Frank Hachiya.

Frank Hachiya Courtesy Defense Language Institute Foreign Lang. Archives

-

![Joan Yasui at the Oregon State Fair, September 1950.]()

Yasui, Joan, at OR State Fair, 1959.

Joan Yasui at the Oregon State Fair, September 1950. Oreg. State Univ. Archives, Extension and Experiment Station Comm., P120:4079

-

Richmond ambassadors, ONLC 00975.

Student ambassadors from Richmond School in Portland, a Japanese language immersion school. Courtesy of Oregon Nikkei Endowment, gift of Renee Ito-Staub, ONLC 00975

-

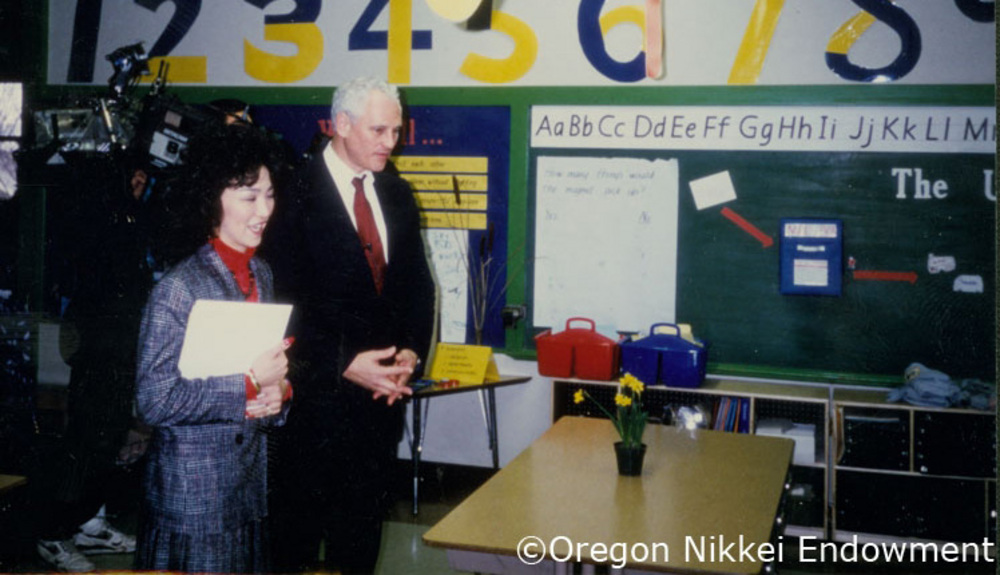

![Item Number ONLC 00977; Governor Neil Goldschmidt visiting Richmond School and principal Renee Ito-Staub. The governor was instrumental in the implementation of the Japanese Magnet Program in the school.]()

Governor Neil Goldschmidt and principal Renee Ito-Staub at Richmond School in Portland..

Item Number ONLC 00977; Governor Neil Goldschmidt visiting Richmond School and principal Renee Ito-Staub. The governor was instrumental in the implementation of the Japanese Magnet Program in the school. Courtesy of Oregon Nikkei Endowment, gift of Renee Ito-Staub, ONLC 00977

-

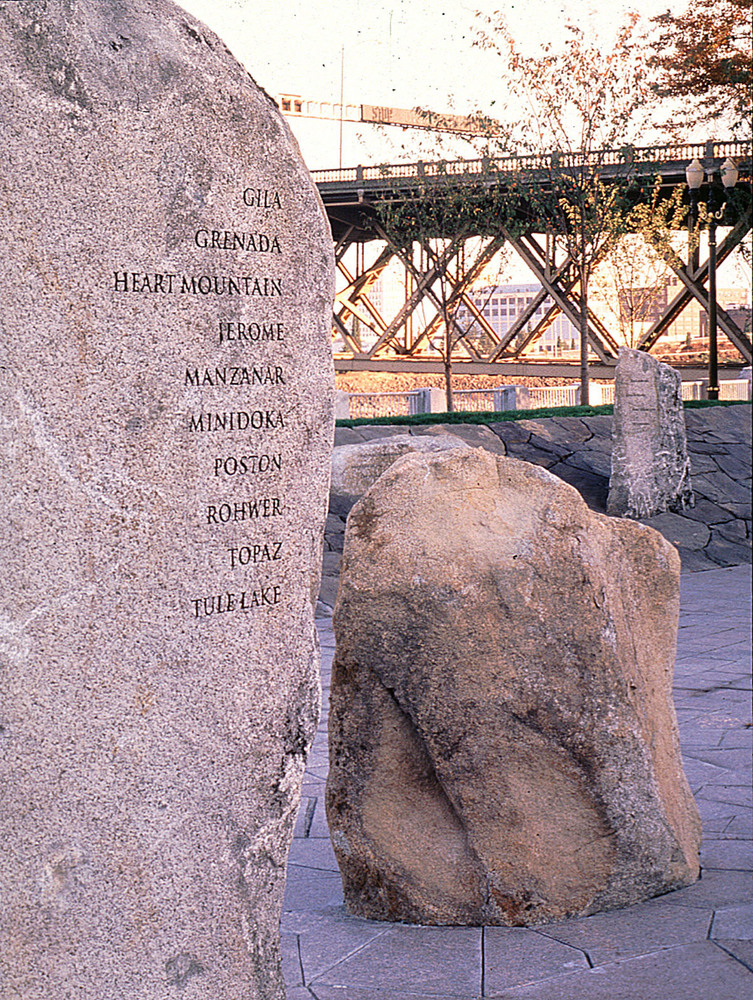

![Japanese American Historical Plaza.]()

Japanese Am. Hist. Plaza 2.

Japanese American Historical Plaza. © Murase Associates, courtesy Oregon Nikkei Legacy Ctr.

-

![Japanese American Historical Plaza.]()

Japanese Am. Hist. Plaza, Steel Bridge behind.

Japanese American Historical Plaza. © Murase Associates, courtesy Oregon Nikkei Legacy Ctr.

-

Oregon Nikkei Legacy Center, outside.

Oregon Nikkei Legacy Center. Courtesy Oregon Nikkei Legacy Center

-

Oregon Nikkei Legacy Center, inside.

Interior of Oregon Nikkei Legacy Center. Courtesy Oregon Nikkei Legacy Center

-

![TIUA Kaneko Commons.]()

TIUA, Kaneko exterior from west2.

TIUA Kaneko Commons. Courtesy Tokyo Int'l Univ. of America

-

![TIUA students volunteering at local humane society.]()

TIUA, volunteer at humane society.

TIUA students volunteering at local humane society. Courtesy Tokyo Int'l Univ. of America

-

![TIUA students tend community garden plot for Marion-Polk Food Share.]()

TIUA, community garden planting.

TIUA students tend community garden plot for Marion-Polk Food Share. Courtesy Tokyo Int'l Univ. of America

-

Japanese Gardens lantern.

Portland Japanese Garden. Photo David M. Cobb, courtesy Portland Japanese Garden

-

![Zig Zag Bridge at Portland Japanese Garden.]()

Japanese Gardens bridge II.

Zig Zag Bridge at Portland Japanese Garden. Photo David M. Cobb, courtesy Portland Japanese Garden

-

![Portland Japanese Garden.]()

Japanese Gardens sand.

Portland Japanese Garden. Photo David M. Cobb, courtesy Portland Japanese Garden

-

![Valerie Otani speaks at the light rail Expo Center station in Portland during the opening of the 2005 Day of Remembrance program.]()

Day of Remembrance, 2005.

Valerie Otani speaks at the light rail Expo Center station in Portland during the opening of the 2005 Day of Remembrance program. Copyright 2005 Rich Iwasaki

-

![Pianist Mike Van Liew accompanies storyteller Alton Chung as Chung relates his program Kodomo No Tame Ni (For the sake of the children), a 2009 Day of Remembrance event at Hipbone Studio in Portland.]()

Day of Remembrance, 2009.

Pianist Mike Van Liew accompanies storyteller Alton Chung as Chung relates his program Kodomo No Tame Ni (For the sake of the children), a 2009 Day of Remembrance event at Hipbone Studio in Portland. Copyright 2007 Rich Iwasaki

-

![May Namba (center) speaks while Larry Matsuda displays photograph at the 2006 Day of Remembrance program at the Portland Metropolitan Exposition Center.]()

Day of Remembrance, 2006.

May Namba (center) speaks while Larry Matsuda displays photograph at the 2006 Day of Remembrance program at the Portland Metropolitan Exposition Center. Copyright 2006 Rich Iwasaki

-

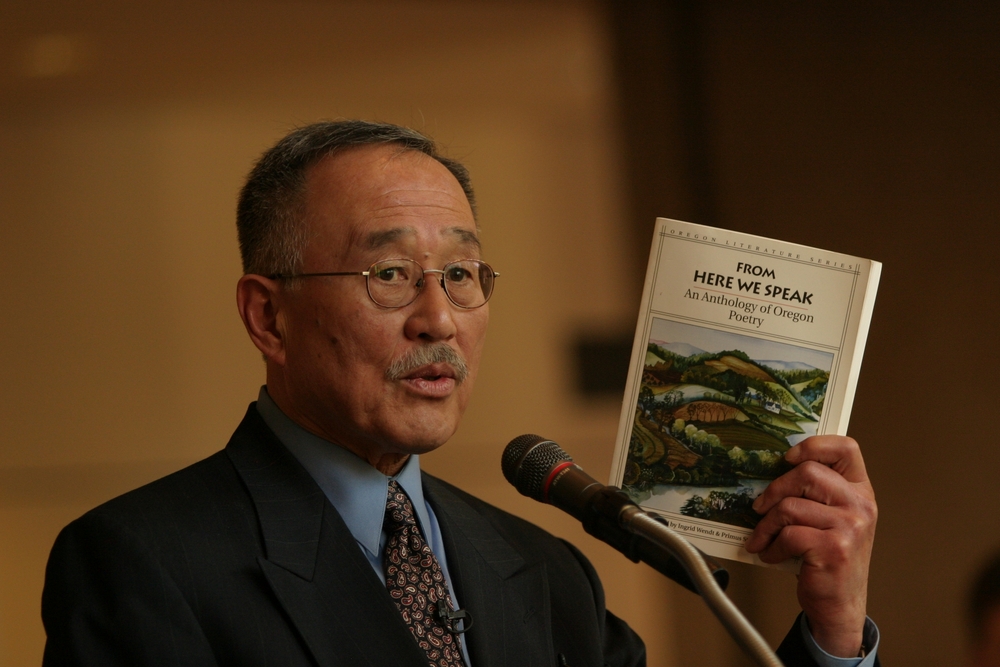

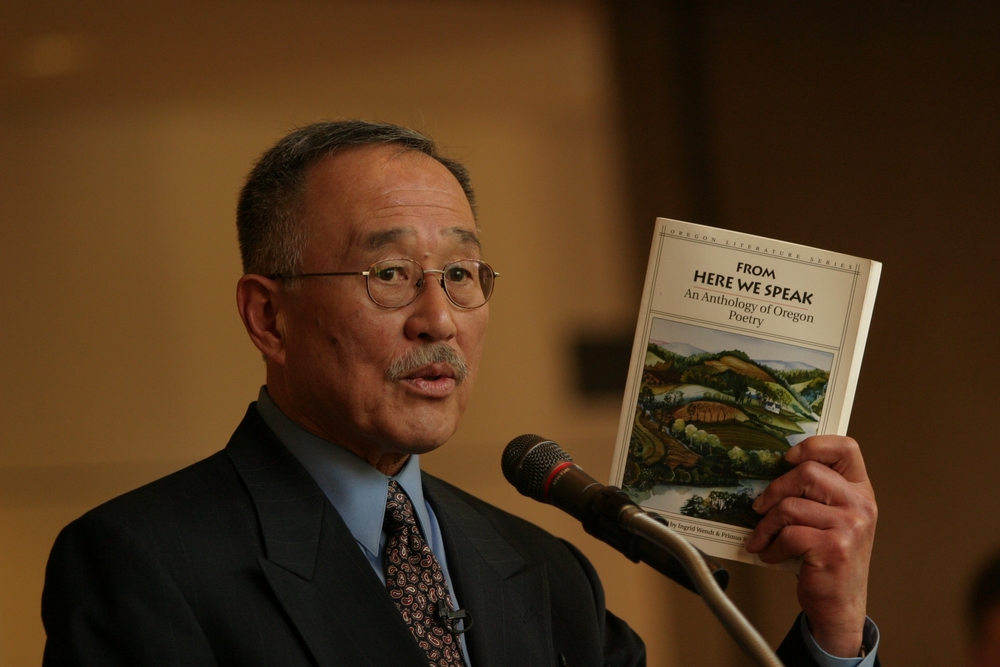

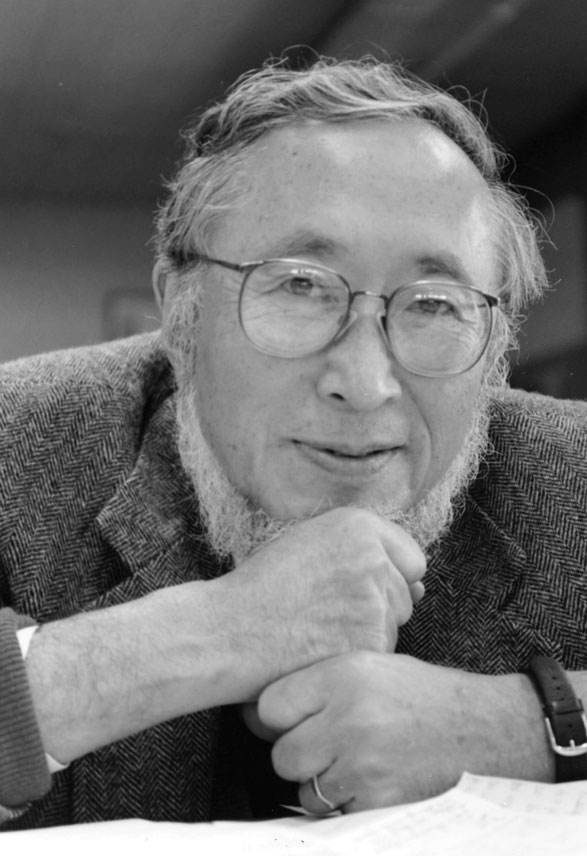

![Lawson Inada with Oregon Poetry Anthology, 2009.]()

Inada, Lawson, with Oregon Poetry Anthology.

Lawson Inada with Oregon Poetry Anthology, 2009. Copyright Craig Walker Communications, Inc.

Related Entries

-

![Benjamin Tanaka (1887-1975)]()

Benjamin Tanaka (1887-1975)

Benjamin Tanaka was a prominent physician in Portland’s Japantown in th…

-

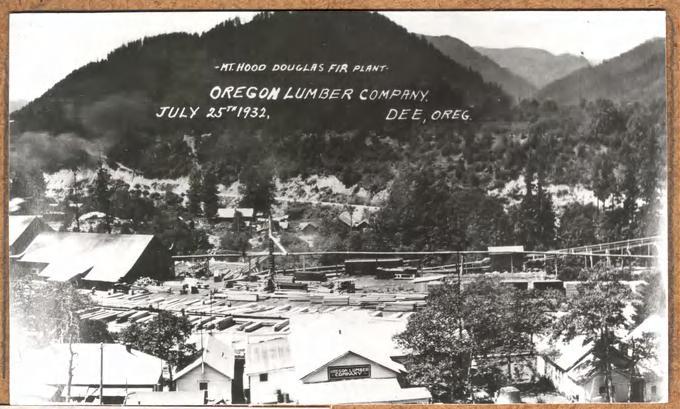

![Community of Dee]()

Community of Dee

Dee refers to a lumber-mill town located on the Middle Fork of the Hood…

-

![Day of Remembrance]()

Day of Remembrance

The Day of Remembrance (DOR) was created as an annual observance of Ex…

-

![Epworth United Methodist Church (Portland)]()

Epworth United Methodist Church (Portland)

From its beginnings as a mission in the late 1890s, Epworth United Meth…

-

![Frank Hachiya (1920-1945)]()

Frank Hachiya (1920-1945)

The name Frank T. Hachiya will forever be linked to Oregon’s Hood River…

-

George Katagiri (1926-2009)

George Katagiri was an educator for most of his life. He began his care…

-

![Hiroshima Peace Trees]()

Hiroshima Peace Trees

From 2019 through 2022, thirty-four communities in Oregon planted a tot…

-

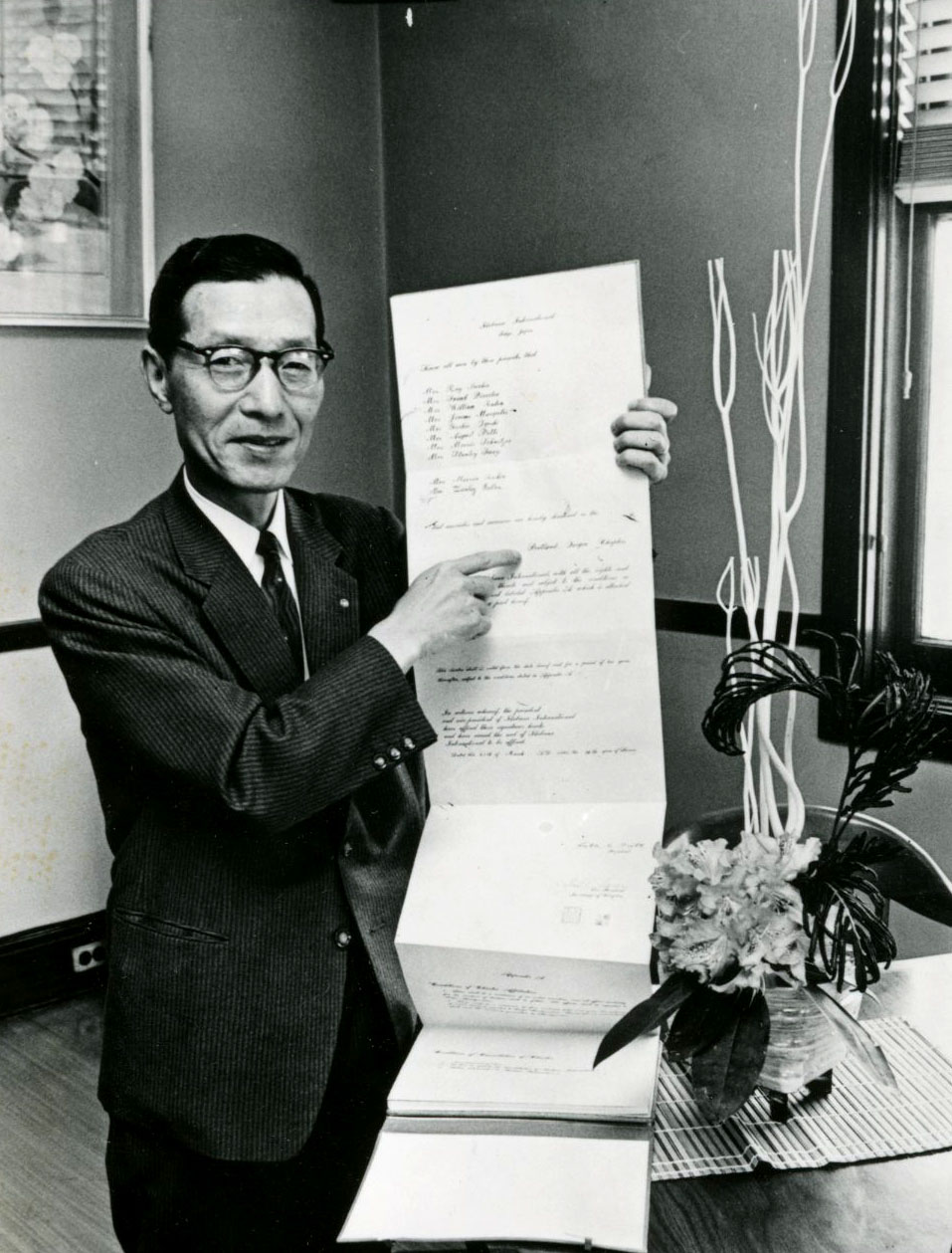

![Ikebana International, Portland Chapter]()

Ikebana International, Portland Chapter

The members of Ikebana International, Portland Chapter #47, have demons…

-

![Iwasaki Brothers Nursery]()

Iwasaki Brothers Nursery

The Iwasaki Brothers Nursery, located on the southern edge of Hillsboro…

-

![Japanese American Historical Plaza (Portland)]()

Japanese American Historical Plaza (Portland)

Using thirteen engraved stones of basalt and granite, the Japanese Amer…

-

Japanese American Museum of Oregon

The Japanese American Museum of Oregon is in Portland’s Old Town, the h…

-

![Japanese American Wartime Incarceration in Oregon]()

Japanese American Wartime Incarceration in Oregon

Masuo Yasui, together with many members of Hood River’s Japanese commun…

-

![Japanese Ancestral Society]()

Japanese Ancestral Society

In the early 1900s, spurred on largely by railroad construction, farmin…

-

![Japantown, Portland (Nihonmachi)]()

Japantown, Portland (Nihonmachi)

Portland's Japantown, or Nihonmachi, is popularly described as having e…

-

Lawson Fusao Inada (1938-)

Poet, writer, and educator, Lawson Fusao Inada is an emeritus professor…

-

![Matsutake (mushroom)]()

Matsutake (mushroom)

On November 13, 1911, mycologist William Murrill collected a mushroom “…

-

![Minoru Yasui (1916–1986)]()

Minoru Yasui (1916–1986)

Minoru Yasui was born in Hood River on October 16, 1916, the third son …

-

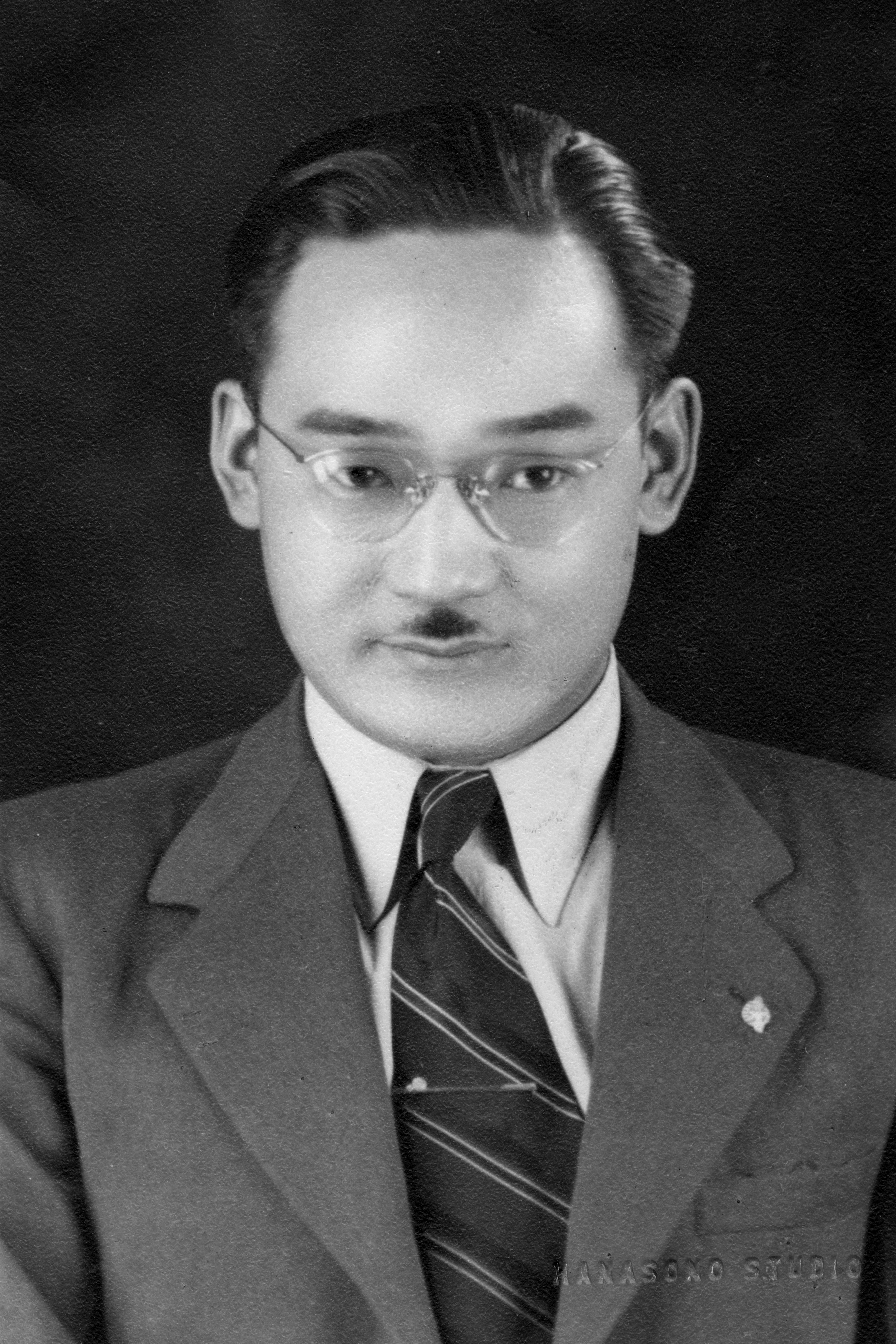

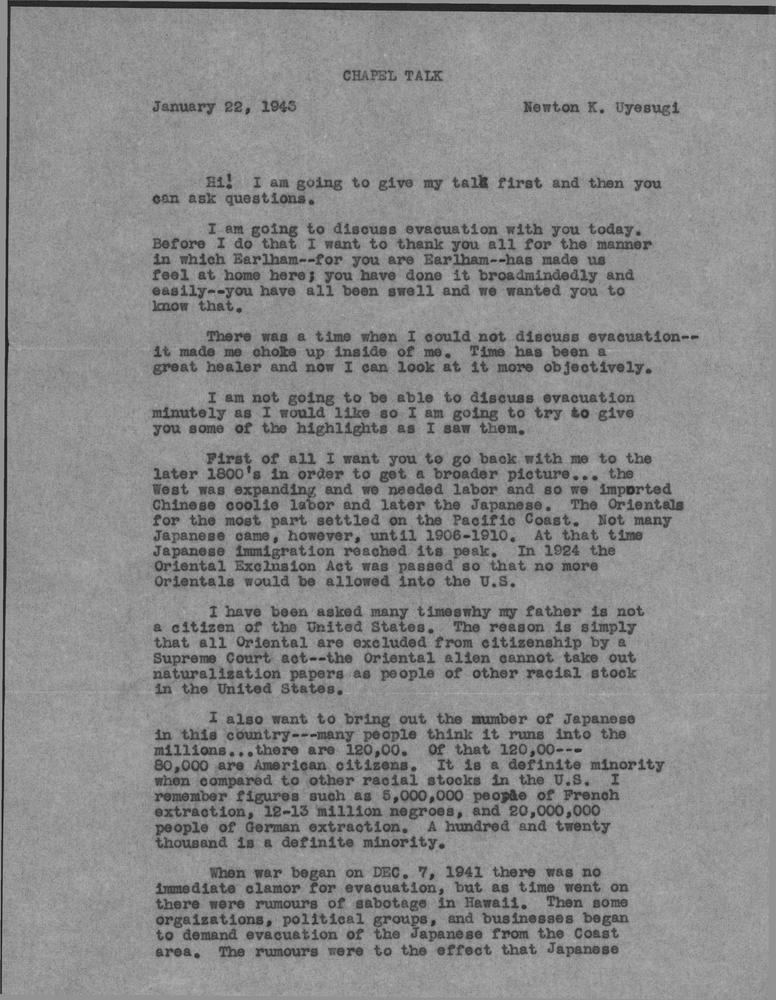

![Newton K. (Uyesugi) Wesley (1917-2011)]()

Newton K. (Uyesugi) Wesley (1917-2011)

Dr. Newton K. (Uyesugi) Wesley, an optometrist and medical doctor in Or…

-

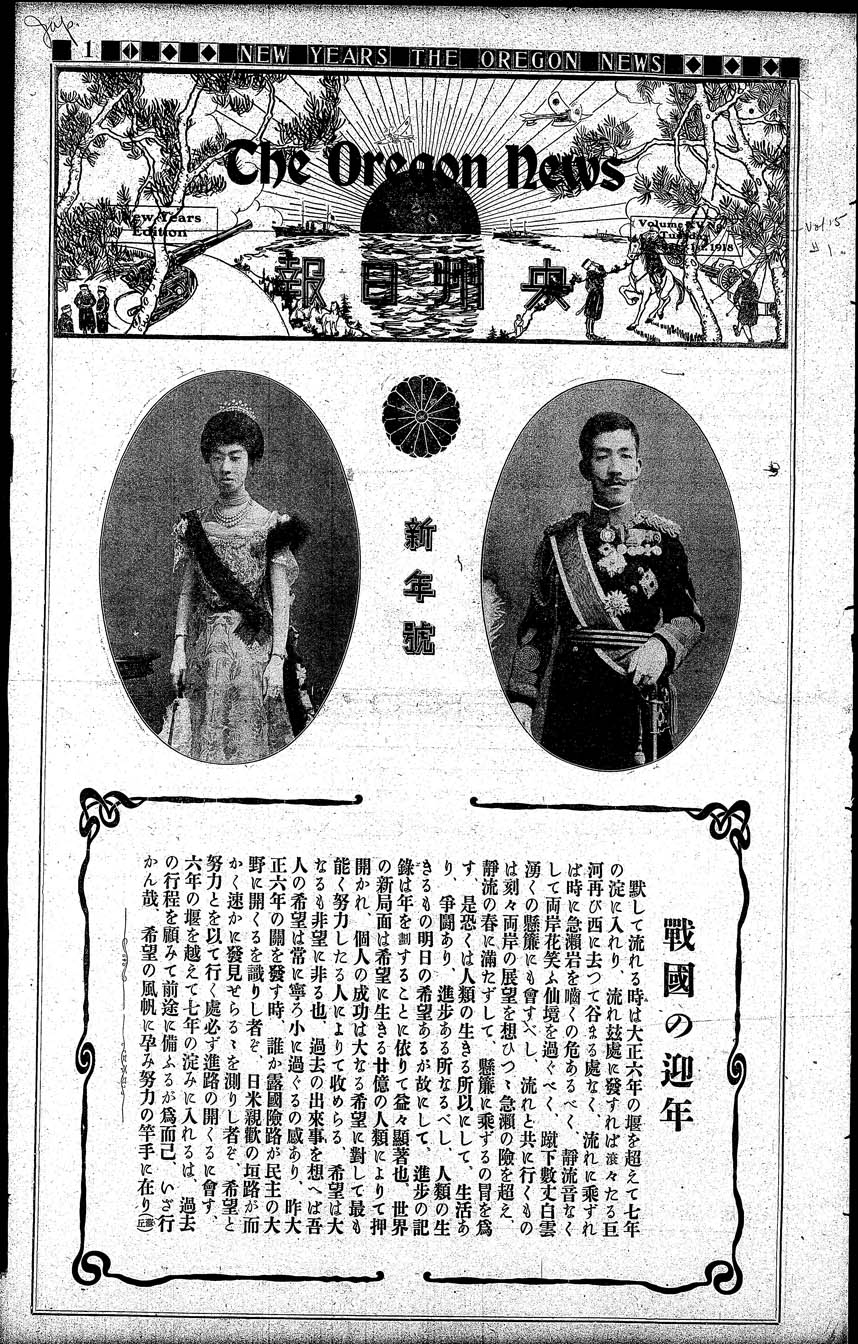

![Oshu Nippo]()

Oshu Nippo

For early Japanese immigrants to Oregon, a Japanese-language newspaper …

-

![Ota Tofu]()

Ota Tofu

Ota Tofu, a small storefront in Portland’s east side, is a cultural and…

-

Portland Japanese Garden

For more than forty-five years, the Portland Japanese Garden has offere…

-

![Portland Temporary Detention Center (Portland Assembly Center)]()

Portland Temporary Detention Center (Portland Assembly Center)

From May 2 to September 10, 1942, an eleven-acre building on the south …

-

![Sahomi Tachibana (1924–)]()

Sahomi Tachibana (1924–)

Sahomi Tachibana is a Japanese American master teacher and performer of…

-

![Sherman Burgoyne (1901-1964)]()

Sherman Burgoyne (1901-1964)

Until he arrived in Hood River in 1942, William Sherman Burgoyne had ne…

-

![Shinzaburo Ban (1854-1926)]()

Shinzaburo Ban (1854-1926)

Shinzaburo Ban was a Japanese businessman who was instrumental in bring…

-

![Shizue Iwatsuki (1897–1984)]()

Shizue Iwatsuki (1897–1984)

A humble wife, mother, and public servant in Hood River, Shizue Iwatsuk…

-

![Tokyo International University of America]()

Tokyo International University of America

In May 1989, the first group of students walked through the doors of th…

-

![Toledo Incident of 1925]()

Toledo Incident of 1925

In 1925, a mob forced a Japanese labor crew to leave Toledo, a communit…

-

![William Sumio Naito (1925-1996)]()

William Sumio Naito (1925-1996)

William “Bill” Naito was born in Portland in 1925. His parents, Hide an…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Daniels, Roger. Asian America: Chinese and Japanese in the United States Since 1850. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988.

Inada, Lawson Fusao, and Mary Worthington. In this Great Land of Freedom: The Japanese Pioneers of Oregon. Los Angeles: Japanese American National Museum, 1993.

Katagiri, George. Nihonmachi: Portland's Japantown Remembered. Portland: Oregon Nikkei Legacy Center, 2002.

Kessler, Lauren. Stubborn Twig: Three Generations in the Life of a Japanese American Family. New York: Random House, 1993.

Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Personal Justice Denied. Washington, D.C.: The Civil Liberties Public Education Fund, 1997.

Tamura, Linda. The Hood River Issei: An Oral History of Japanese Settlers in Oregon's Hood River Valley. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993.