From May 2 to September 10, 1942, an eleven-acre building on the south side of Marine Drive in Portland, just west of the Interstate Bridge, was transformed into the Portland Temporary Detention Center, also known as the Portland Assembly Center. The Pacific International Livestock Exposition, located next to stockyards and a slaughterhouse, had hosted livestock shows, auctions, rodeos, and agricultural displays. Now it was a prison for more than 3,800 Japanese Americans from northwest Oregon and central Washington. Of the fifteen temporary detention centers in the western United States operating during the summer of 1942, the Portland Temporary Detention Center was the only one in Oregon.

On February 19, 1942, two months after the United States declared war on Japan, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 authorizing the establishment of “military areas” where “any or all persons” could be excluded as “protection against espionage and…sabotage.” The order made possible the removal of all persons of Japanese ancestry from “exclusion zones” in California, western Oregon and Washington, and southern Arizona. While War Relocation Centers, as they were called, were being constructed in the interior of the country, temporary detention sites were needed to hold 92,000 people.

The Wartime Civil Control Administration, part of the U.S. Army’s Western Defense Command, selected the Livestock Exposition site in Portland because it met the four requirements established by the government: pre-existing facilities could be adapted for shelter; power, light, and water sources were nearby; distance from the center to the people being removed from the area was short, and connecting rail and road networks were good; and there was space inside the enclosure for recreation and allied activities.

Notices to “All Persons of Japanese Ancestry” were posted on buildings, billboards, and telephone poles in exclusion areas, and a “responsible family” was required to register at a civil control station. The notices instructed all persons to appear for evacuation and made it clear what they were allowed to take with them. All Japanese Americans in the exclusion zones had one week to close their businesses, lease or sell their farms, store or sell their belongings, pack items to take with them, and report to the detention centers. This meant forfeiting the value of years of work and selling belongings for very little, giving them away, or deciding to leave them behind. In Portland, notices were posted on April 28, and all persons were required to report to the detention center by noon on May 5.

By May 1942, the animal stalls at the Livestock Exposition had been converted into quarters measuring about ten-by-fifteen feet, one per family. Each person had a cot and a straw-filled bag for a mattress. Rooms were open at the top, doorways were covered by canvas flaps, and the dirt floors were covered with wood planks. Single men were assigned beds in a dormitory. The separate latrines and showers for women and men lacked partitions for privacy. The stench of stock manure was pervasive.

Outside the main building were a small hospital, a laundry, a clothesline, a ball field, children’s play space, and a Military Police barracks. Railroad tracks ran along the south side of the compound, and the entire center was surrounded by barbed wire. An area on the north side provided relief from the oven-like temperatures inside. On weekends, the center became a tourist attraction, with some gawkers pointing out acquaintances inside the barbed wire and others hurling insults.

Work at the center was performed by the prisoners, who were paid a small monthly wage: eight dollars for unskilled labor, twelve dollars for skilled labor, and sixteen dollars for professional work. All of the labor was directed by a white administrative staff. A newspaper, the Evacuazette, was staffed by prisoners who were in their late teens and early twenties, and all of the stories were subject to editing and approval by the center's manager before the paper was mimeographed and distributed. Editorials encouraged calm and thoughtful action, and hand-drawn cartoons poked fun at the center’s lack of privacy, the challenges in dating, and fly infestations.

During this time, the roles of Issei (noncitizen immigrants) and Nisei (their American-born children) were shifting. The young people had opportunities to socialize and earn money, while the influence and authority of their parents diminished. An essay in the August 4 Evacuazette editorialized that the Nisei were better educated in the ways of American living and could better meet the community's needs.

By spring 1942, sugar beet farmers in eastern Oregon, under contract with the Amalgamated Sugar Company, were experiencing a severe labor shortage. Both farmers and the government saw imprisoned Japanese Americans as a solution, and Governor Charles Sprague agreed to support them. General John J. DeWitt, head of the Western Defense Command, issued an order on May 20 that allowed four hundred detainees from the Portland center to work as field laborers in Malheur County. The next day, fifteen men left the Portland center for farm labor camps in eastern Oregon. After hearing positive reports from the workers, others at the center volunteered. Some went to escape the unhealthy conditions, and others needed the wages. Some families volunteered, hoping they could live and work together in a place without barbed wire and armed soldiers. Workers agreed to return to the Portland Temporary Detention Center after the work was completed and to leave the work camp only with an official or a farmer. Their safety was guaranteed by state and local officials.

Trains carrying Portland detainees to War Relocation Centers in Wyoming and Idaho left the Portland center in late August and early September. Almost forty years after her removal from the city, Emi Somekawa testified about her experience as a young wife, mother, and nurse: “One day we were free citizens, residents of communities, law abiding, protective of our families, and proud. The next day we were inmates of cramped, crowded American style concentration camps, under armed guards, fed in mess hall lines, deprived of privacy and dignity, and shorn of our rights.”

The building that housed the Portland Temporary Detention Center is now part of the Portland Expo Center. East of the building is Voices of Remembrance (2004), a commemorative work of art designed by Valerie Otani—wooden torii gates strung with metal tags, one for each person held at the center in 1942.

-

![]()

Portland's Pacific International Livestock Expo Building served as a Japanese Assembly Center in 1942.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 28157

-

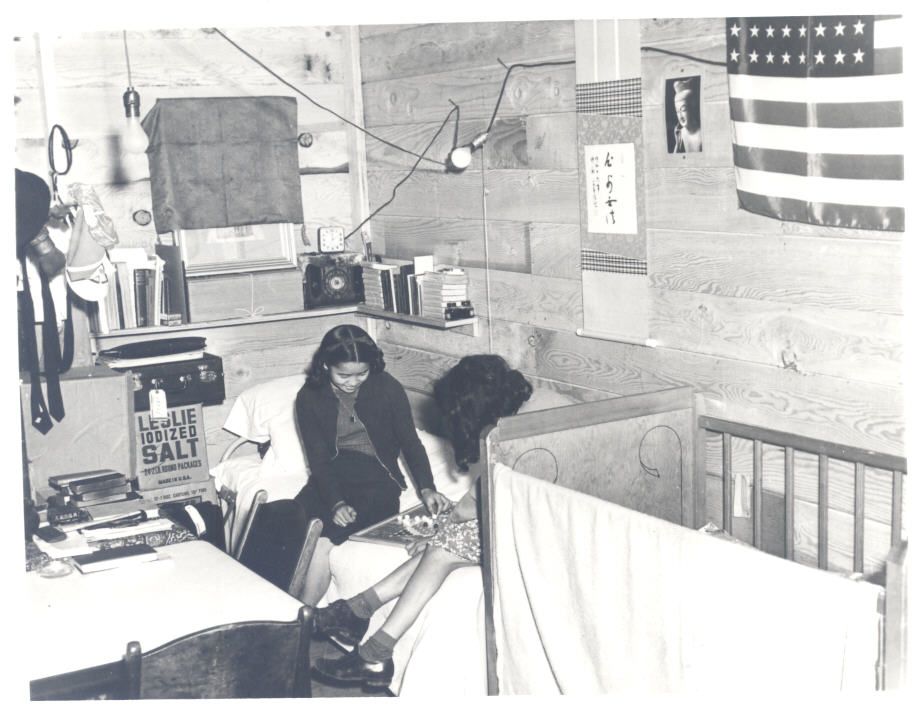

![Hiroko Terakawa and Lilian Hayashi in an apartment in the Portland Assembly Center.]()

Living quarters in the Portland Assembly Center, 1942.

Hiroko Terakawa and Lilian Hayashi in an apartment in the Portland Assembly Center. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi28163

-

![Nikkei were evacuated and incarcerated in Portland's Pacific International Livestock and Exposition Center, which became the Assembly Center.]()

People being evacuated to the Assembly Center, 1942.

Nikkei were evacuated and incarcerated in Portland's Pacific International Livestock and Exposition Center, which became the Assembly Center. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 497560

-

![]()

Soldiers remove people to the Portland Assembly Center, 1942.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 48789

-

![]()

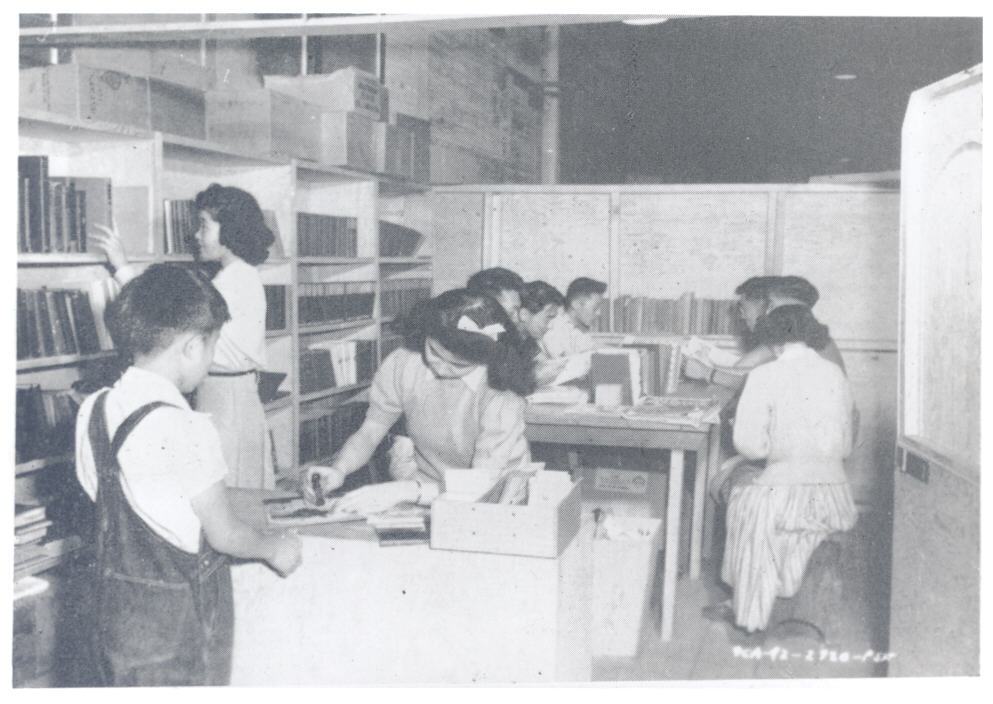

Portland Assembly Center library, 1942..

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi97763

-

![]()

Women working in the Portland Assembly Center, 1942.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi84850

-

![]()

Detainees at the Portland Assembly Center published the Evacuazette newspaper, 1942..

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi49758

Related Entries

-

![Japanese Americans in Oregon]()

Japanese Americans in Oregon

Immigrants from the West Resting in the shade of the Gresham Pioneer C…

-

![Japanese American Wartime Incarceration in Oregon]()

Japanese American Wartime Incarceration in Oregon

Masuo Yasui, together with many members of Hood River’s Japanese commun…

-

![Oregon Plan]()

Oregon Plan

The Oregon Plan, implemented in May 1942, led to the organization of th…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Burton, Jeffery F., Mary M. Farrell, Florence B. Lord, and Richard W. Lord. Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002.

California State University, Dominguez Hills Archives and Special Collections CSU Japanese American Digitization Project.

Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997.

Daniels, Roger. Concentration Camps: North America Japanese in the United States and Canada During World War II. Malabar, FL: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Co. Inc, 1981.

DeWitt, John L. Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942. Washington D.C.: U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1943. http://.www.archive.org/details/japaneseevacuati00dewi.

Fiset, Louis. “Thinning, Topping, and Loading: Japanese Americans and Beet Sugar in World War II.” Pacific Northwest Quarterly 90.3 (Summer, 1999): 134, 137.

Uprooted: Japanese American Farm Labor Camps during World War II (exhibit and oral histories).

“Ready for Opening of Pacific International Livestock Exposition.” Sunday Oregonian, Farm, Home and Garden, September 28, 1941.