Oregon’s High Desert is a place apart, an inescapable reality of physical geography. The region forms an extensive area that is substantially different in climate, elevation, and hydrology from any other part of Oregon, and it has a distinctive human history.

Geography

The geographic definition of the High Desert is not bounded by any formally recognized limits. The term “high desert” may have first appeared on Oregon maps in the early twentieth century to designate a rocky upland area near the center of the state—northernmost Lake County and southeastern Deschutes County. By the late twentieth century, the news media and others had used the term for virtually all of the state east of the Cascade Range, excluding the Blue Mountains. Neither one of these definitions is particularly useful. The smaller, older, cartographic “high desert” has become an archaic term, while the newer, more expansive “high desert” includes parts of eastern Oregon that are neither “high” nor “desert.”

To give the region a useful definition, the approximate boundaries of the High Desert include most of the southeastern quarter of the state, including nearly all of Lake and Harney Counties, the southern three-quarters of Malheur County, the southeastern one-third of Deschutes County, and a sliver of southeastern Crook County. The terrain that is most properly considered the Oregon High Desert, then, includes virtually all of Oregon’s share of the Great Basin, that vast portion of the Intermountain West characterized by interior drainage (that is, where no river waters flow to the ocean). The High Desert also includes the upper watershed of the South Fork of the Crooked River (a tributary of the Deschutes River) and the upper drainages of the Owyhee and Malheur Rivers (tributaries of the Snake River).

The land encompassed by this hydrological definition is comparatively high, with elevations averaging between 4,000 and 6,000 feet above sea level. Most of the area receives well under 15 inches of annual precipitation (except for those few mountain ranges that rise high enough to receive considerable snowfall). Some areas, such as the Alvord Basin, can receive fewer than 5 inches in a year.

In contrast to the sagebrush-covered uplands of north-central Oregon's Deschutes–Umatilla Plateau, the high desert of southeastern Oregon has less than half the average number of frost-free, growing-degree days. Although the two regions share a similar aridity, most of southeastern Oregon lacks the deeper, more fertile soils and abundant irrigation opportunities of the Deschutes–Umatilla Plateau. As a consequence, the former remains a sparsely inhabited rangeland while the latter has a healthy farming population.

Geology

Virtually all of the High Desert consists of volcanic rocks; even its sedimentary deposits are derived largely from volcanic ash that settled in ancient lake basins. The overwhelming majority of the terrain was formed by a deep sequence of liquid lava flows (mostly basalt) that repeatedly erupted from miles-long vents and spread across thousands of square miles of the interior Northwest. Most of the High Desert’s flows occurred between about 30 and 10 million years ago.

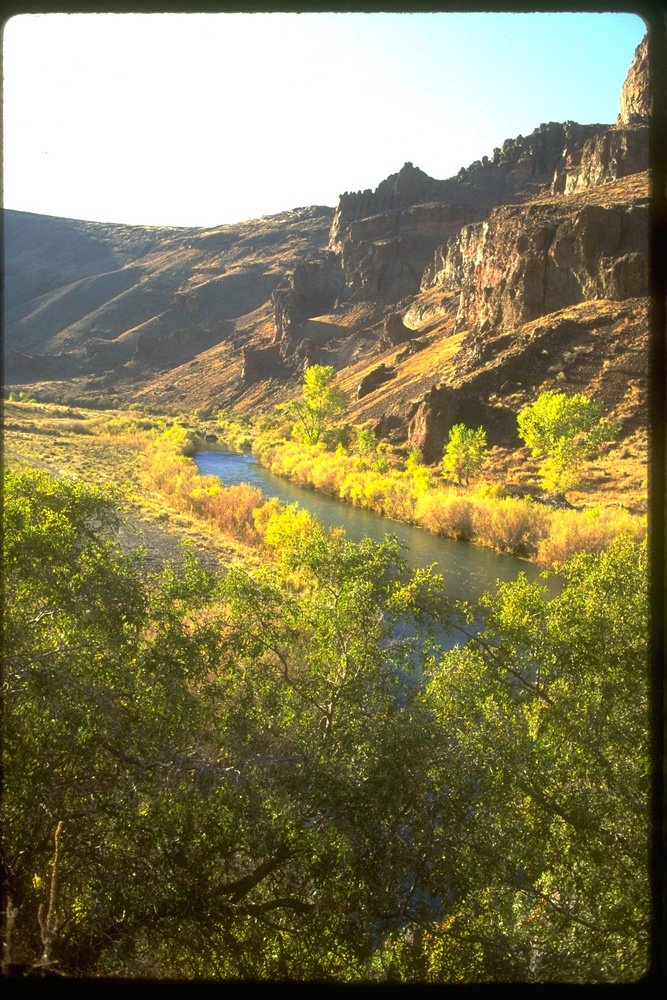

Geographers divide the High Desert into three physiographic provinces. On the east is the Owyhee Uplands—a broad, open terrain incised by the canyons of the upper Owyhee and Malheur Rivers. The High Lava Plains in the north includes the original, smaller area that was called the “high desert” during the 1800s. The area is distinguished by rocky, rolling uplands with poorly developed stream drainages.

The third and largest section is the Basin and Range province, where during the Pliocene Epoch (ten to two million years ago) the landscape south of the High Lava Plains was altered by faulting, caused by the forces of global plate tectonics. Some parts of this volcanic terrain were thrust upward into a series of linear (generally north-south and miles long), fault-block ranges such as the Warner Mountains, Abert Rim, and Steens Mountain. The terrain located between the elevated ranges subsided to form the area’s characteristic lower, broad, and almost level basins, including the Chewaucan and Alvord Basins and the Warner and Catlow Valleys.

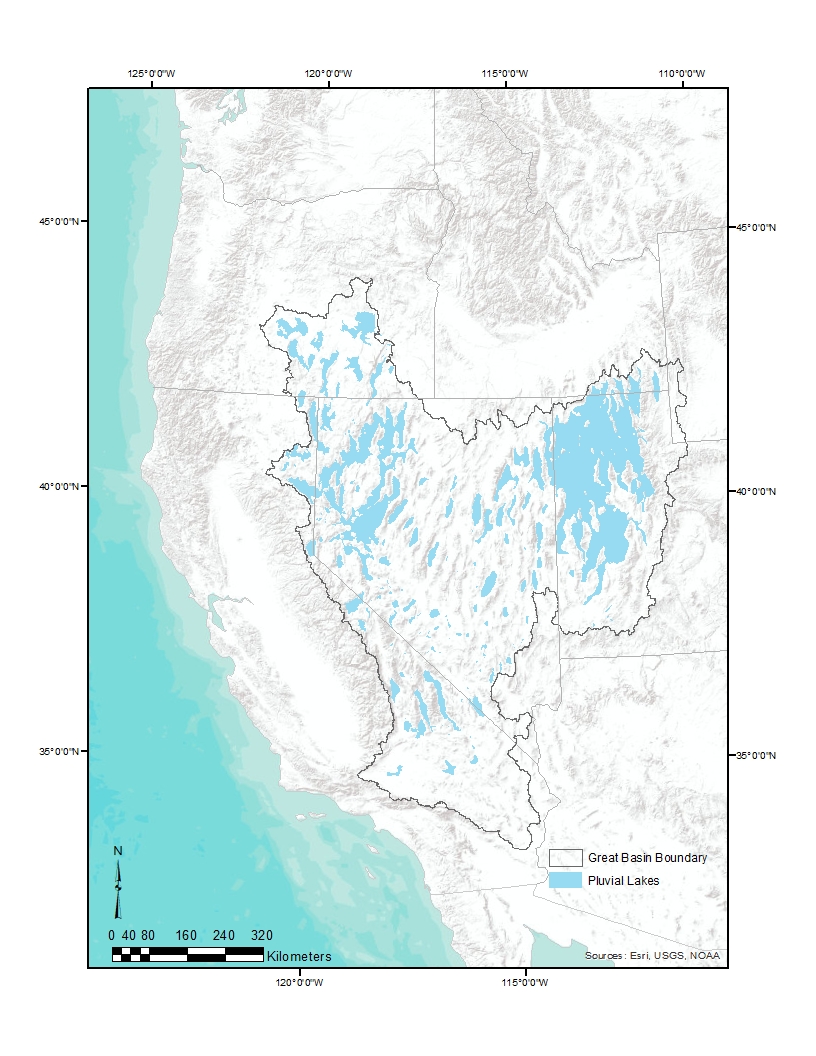

During the Pleistocene Epoch, or Ice Age (from 2 million years to about 12,000 years ago), when the weather was slightly colder and wetter than it is today, many of these enclosed basins became lakes, some of them close to three hundred feet deep. At the highest elevations, glaciers formed and carved large U-shaped valleys into the layers of basalt. Beginning after about 12,000 years ago—as the climate warmed and dried—the glaciers disappeared and the large bodies of fresh water steadily shrank to become shallow, alkaline lakes such as Abert Lake, dry playas like the Alvord Desert, and sagebrush-filled expanses such as the Catlow and Fort Rock Valleys.

There are a few places in the High Desert, such as Jordan Craters, where volcanism occurred as recently as three thousand years ago. The continuing geological influence of the deep sources of underground heat accounts for the High Desert’s geothermal resources, including Alvord Hot Springs and Lakeview’s Hunter Hot Springs.

Origins of the Name “High Desert"

Before the late twentieth century, when the name “High Desert” came to be widely used to describe the region, EuroAmerican explorers and settlers had applied other descriptive names to southeastern Oregon’s dry landscape. From the 1850s into the 1890s, the name “Sage Plains” appeared on maps of Oregon to identify the region. Cartographers also used the names “Sage Desert” and “Great Sandy Desert,” the latter appearing on a National Geographic map as late as the 1970s. As travel across the area increased after 1900, some cartographers placed the simple warning “Desert” on their maps. It was apparently during the 1920s that long-distance travelers braving southeastern Oregon’s few gravel-paved highways came to know the region as the “Oregon Desert.”

During the early twentieth century, ranchers and dry-farm homesteaders in northern Lake County and southeastern Deschutes County popularized the term “low desert” for the flat expanse of the Fort Rock-Christmas Lake Valley basin. They used “high desert” to identify the higher-elevation, rockier upland immediately to the north, a place that is now traversed by Highway 20 between Riley and Millican. Following World War II, the term “Oregon High Desert” became popular and was increasingly applied to a much larger geographic area.

Contributing directly to the popularization of the term, some geographers and plant ecologists regularly applied the term “high desert” to huge portions of the steppe lands of the northern Great Basin, including northern Nevada and Utah, southernmost Idaho, and southeastern Oregon. This use of “high desert” for the large region of bunchgrass and sagebrush steppe vegetation in the Intermountain West was used to differentiate it from the extremely arid deserts of the American Southwest (e.g., the Mohave, Colorado, and Sonoran). The term “high desert” was also applied to similar places in Central Asia. “High Desert” is now relatively well accepted as the name of southeastern Oregon’s high-elevation, semi-arid-to-arid steppe lands.

First Peoples

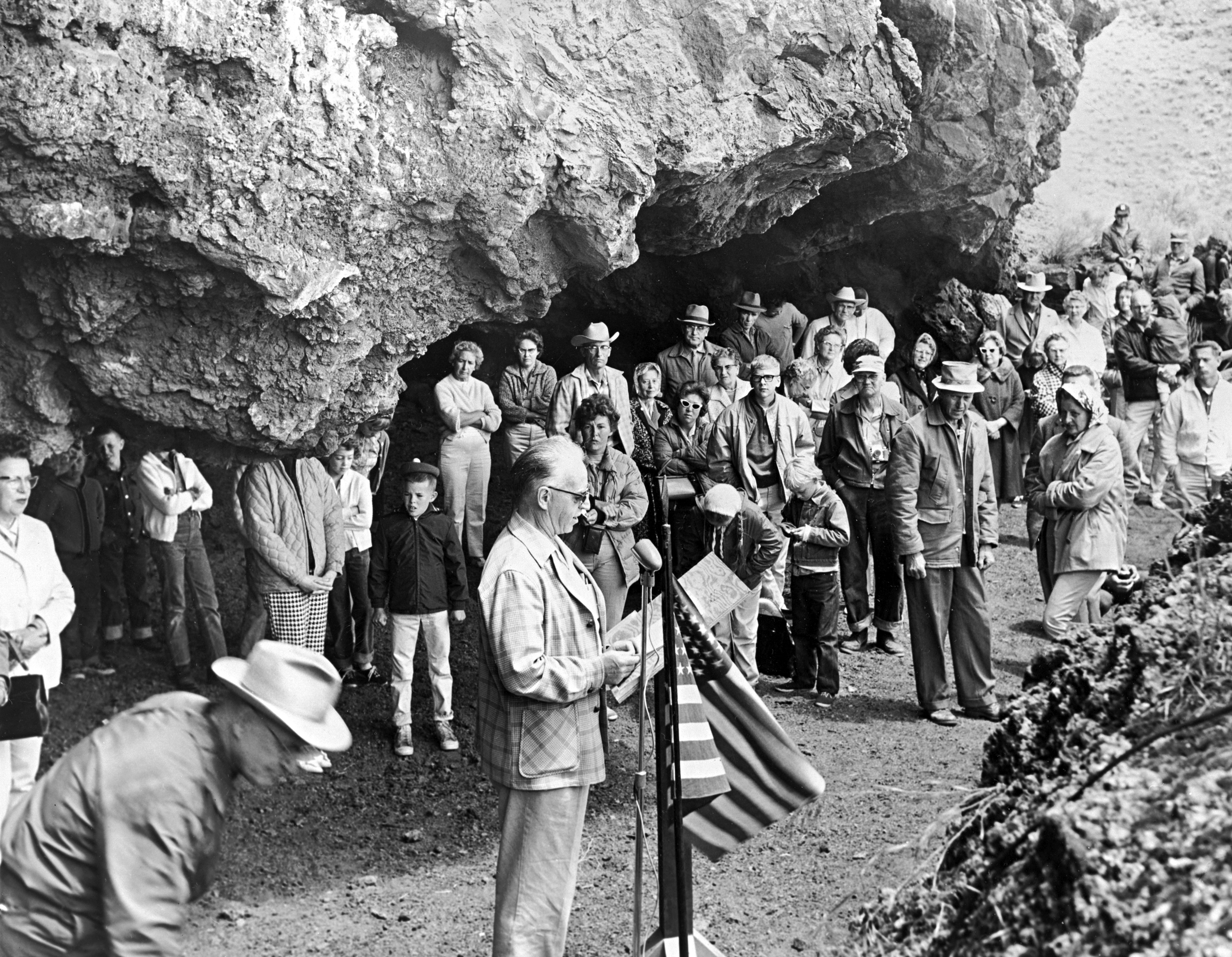

Native people made their homes in the High Desert beginning at least 14,000 years ago, and there is evidence that they hunted late Ice Age’s megafauna until they became extinct by the close of the Pleistocene Epoch. Since the 1930s, a great deal of archaeological investigation in the region has played an important role in documenting the arrival of human beings in the Americas. Archaeologists found 9,000-year-old sagebrush-bark sandals at Fort Rock Cave; 11,000-year-old chipped-stone, fluted-style (Clovis) obsidian spear points near Alkali Lake; and human coprolite (fossilized feces) that is more than 14,000 years old at Paisley Caves.

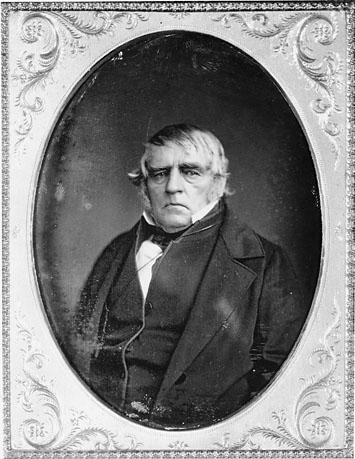

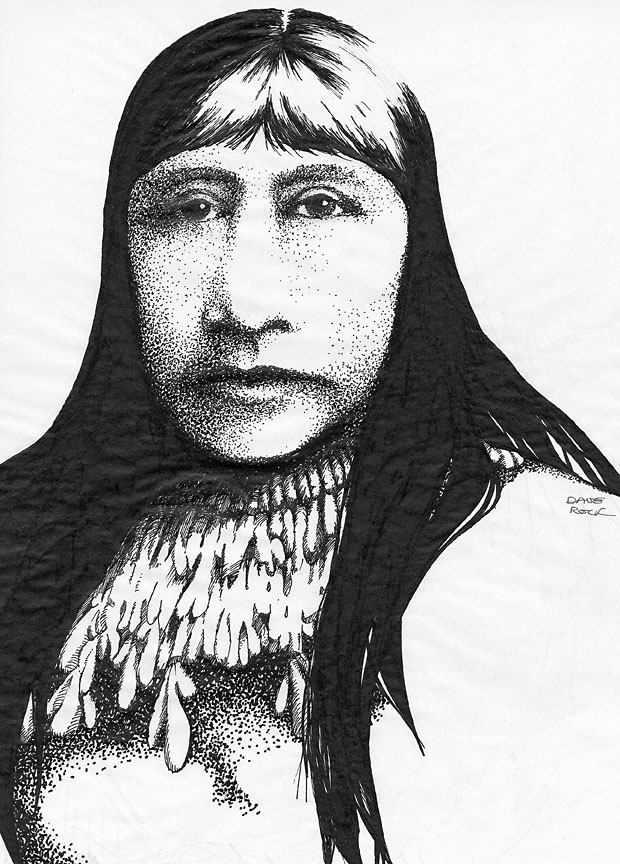

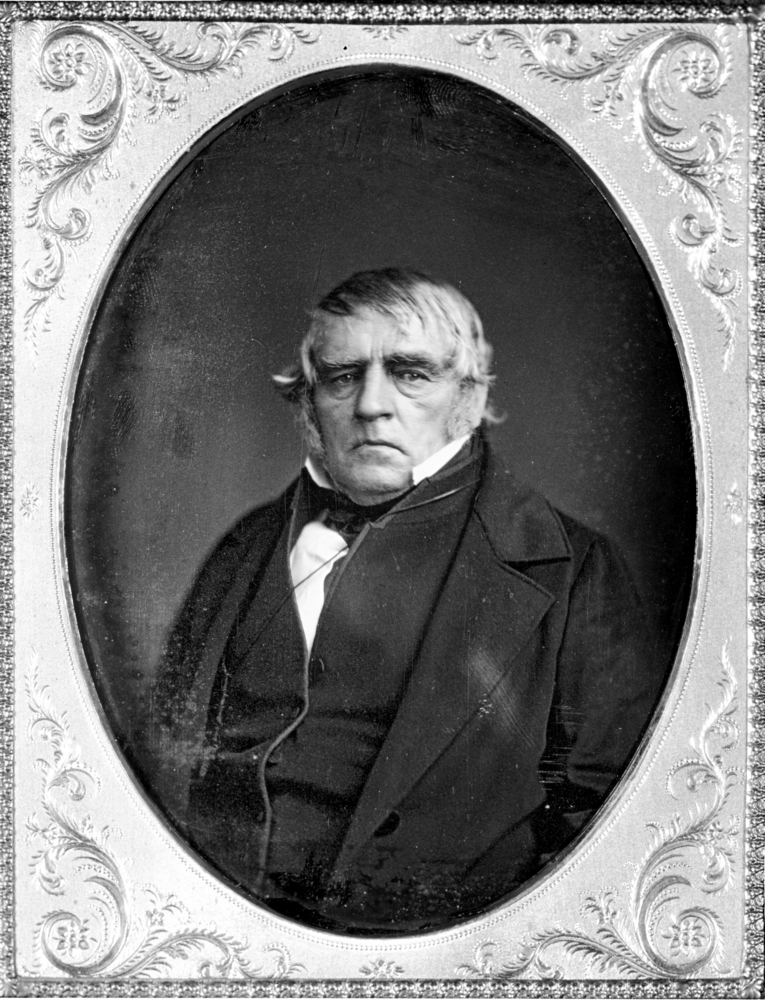

Beginning in the early nineteenth century, non-Native travelers recorded descriptions of the stark desolation of the High Desert. Fur trader Peter Skene Ogden, for example, remarked on the endless “wormwood” (sagebrush), and in 1827 he recounted with much surprise the large number of “Snake” Indians he encountered in Warner Valley. These were Northern Paiutes, part of a language group that included the Southern Paiute, the Ute, the Shoshone, and the Bannock. During the previous millennium, this group of people had moved north and east from their ancient homeland in the southernmost Great Basin.Some archaeologists and linguists believe that they arrived in southeastern Oregon only a few centuries ago, with the Northern Paiute replacing earlier peoples who had lived in the region when the climate had been wetter. Before them, even earlier groups had lived in the region, and all had subsisted on the waterfowl-rich swamps and other wetlands in some of the basins, as well as from the bighorn sheep and other animals that ranged the uplands.

Through communal jackrabbit drives and the gathering of biscuitroot and other roots, seeds, and bulbs, Native people acquired abundant food and materials for clothing from the sage plains. Referred to by archaeologists as the “Desert Culture,” the Northern Paiute and, before them, the post-Ice Age peoples of the Great Basin and adjacent regions adapted and endured in an environment characterized by limited water and sustaining resources.

EuroAmerican Exploration and Early Settlement

Hudson's Bay Company trader Peter Skene Ogden in the late 1820s and U.S. Army officer John Charles Frémont in 1843 were the first whites to explore the region's terrain. In the mid-1840s, a few wagon trains of Willamette Valley-bound emigrants struggled across the High Desert on their way to the mountain passes of the Cascade Range. During the 1860s, with the discovery of gold in the John Day River country to the north, the U.S. Army undertook the final pacification of the Northern Paiute in brutal campaigns known as the Snake Indian Wars. In 1878, due to the participation of some Paiutes in the Bannock War, the U.S. government abolished the Malheur Reservation, which had been set aside for the Paiute, and opened the land to ranchers.

Soon after 1870, cattlemen established the earliest ranching operations in the Oregon High Desert—the first permanent EuroAmerican settlers in the region. With completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, railheads were located in northern Nevada at towns such as Winnemucca and Elko. Among the region's early cattle barons were Peter French, John Devine, Henry Miller, and Charles Lux. The owners and their employees (many of them Californio vaqueros) came from the vast ranches of California’s Central Valley, driving large herds of cattle north to graze the bunchgrass ranges of southeastern Oregon and northern Nevada. A number of large ranches were established in the High Desert during the 1870s and 1880s, especially in the rangelands of Harney County. The ZX Ranch, near Paisley in Lake County, was established in the late 1880s as an investment of the California-owned Chewaucan Land and Livestock Company. In southeastern Deschutes and Crook County, the GI Ranch covered an area some forty-by-seventy miles in size.

For decades, the Oregon High Desert, together with adjacent parts of Idaho and Nevada, became an economic colony of San Francisco and Sacramento. Years later, adjacent portions of southwestern Idaho, southeastern Oregon, and northernmost Nevada became known as the ION Country, a place whose inhabitants often shared more with each other than they did with people who lived in distant parts of the three states.

Unlike the Great Plains’ cattle-ranching culture, which originated in Texas, the ION’s ranching heritage came from California, where vaqueros herded cattle on horseback. In the ION and elsewhere in the Great Basin, the word buckaroos is a variant of that Spanish term. The ranching culture of the ION produced unique styles of saddles (such as the high-backed Lakeview saddle), tack, chaps, and fence construction (such as stacked-stone fences and corrals made of willow branches woven basket style into pairs of upright juniper posts). The arrival of Irish and then Basque sheepmen added another cultural component to the ION country. The Irish generally lived and worked in parts of Lake County, while the Basques lived in towns such as Burns and Jordan Valley. The herds of wild horses that can be seen off Highway 140—hopefully but inaccurately named the Winnemucca-to-the-Sea Highway in the 1960s—are descendants of the huge herds raised by ranchers in the early twentieth century for the hard duty of supplying the muddy trench warfare of World War I.

Twentieth-Century Settlement

The High Desert, like many other parts of the semi-arid West, experienced a brief but heavy influx of settlers with the dry-farming homestead boom of 1909-1920. The main cause of the boom was the passage of the 1909 Enlarged Homestead Act (also called the Mondell Act, for the Wyoming congressman who championed it). This legislation, which doubled the acreage for homestead claims in several Western states from the 1862 Homestead Act's original 160 acres to 320 acres, was meant to provide sufficient land to new settlers to "make a go of it" by dry-farming the harsh semi-arid lands where irrigation was not available. During those years, hundreds of cabins were built by would-be grain farmers, who established hamlets such as Fremont and Fort Rock in northern Lake County and Blitzen in Harney County’s Catlow Valley. The farmers scrabbled by until the realities of the region’s short growing season and its want of rain ended the boom.

During the Great Depression, cattle prices plummeted and, with the influence of the 1935 Taylor Grazing Act, the rangeland free-for-all in the High Desert came to an end. Three decades earlier, in 1908, Theodore Roosevelt had established the nation's first federal wildlife refuge as habitat for migratory birds in northern Harney County, surrounding Malheur and Harney Lakes and extending for miles along the marshes of the Blizten River.

The New Deal and the postwar periods brought new post offices, highways, range and wildlife-habitat improvements, fire suppression, and irrigation developments to the High Desert; and federal dollars remain a major part of the region’s economy. The overwhelming majority of land in the region is owned by the federal government, which acquired much of it by treaty and conquest in the nineteenth century. The Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Forest Service, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service account for a substantial portion of the region’s current population and its payroll.

Cultural Heritage

The decades of the cattle barons left a legacy of terminology, ranch house and barn architecture, social pastimes, clothing, and stories. Reub Long, a longtime rancher at Fort Rock, captured the region's ranching-related folklore, jokes, and stories in The Oregon Desert, a 1964 book he wrote with Oregon State University range specialist E.R. Jackman. The sheepherders left a fascinating record of their lives and work in the High Desert in the form of carvings, known as dendroglyphs, in the bark of quaking aspen trees. The inscriptions range from names and dates to short poems, complaints about loneliness, and the kind of crude drawings sometimes found on bathroom walls.

In addition to poets such as C.E.S. Wood, dry-farm homestead wives, schoolteachers, and others wrote desert-themed poetry, which was published in newspapers or memoirs. The poems from that era evoke the stark beauty of the region and the loneliness of life there. In the late twentieth century, the popularity of cowboy poetry has enticed some High Desert poets to read their work and sing their songs at the annual National Cowboy Poetry Gathering in Elko, Nevada.

There are a few novels and short stories set in the Oregon High Desert. H.L. Davis set the closing scenes of his Pulitzer Prize-winning Honey in the Horn somewhere in the region, and Richard Brautigan employed a fantastical but humorous and recognizable version of early twentieth-century Lake County as the setting for his bizarre novel The Hawkline Monster. William Kittredge, from Lake County and one of the best contemporary writers about the West, describes life in the High Desert in Owning it All, a collection of essays that paints an unforgettable image of the Warner Valley during the postwar years.

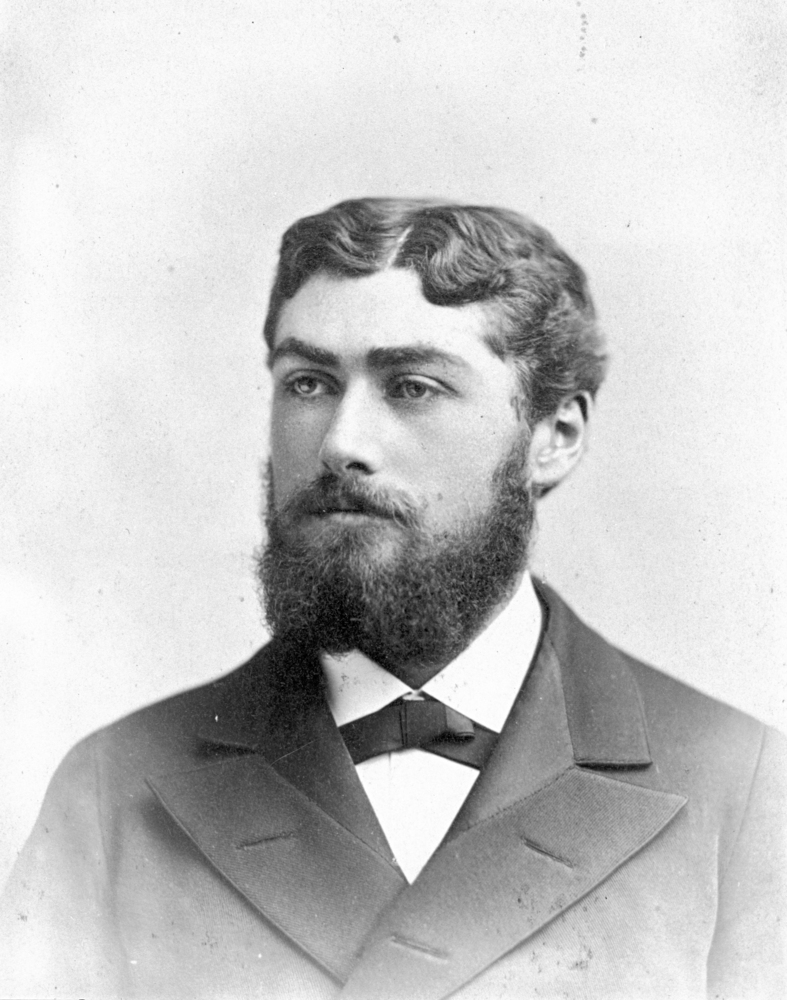

The region's petroglyphs and pictographs are the earliest works of art created by residents of the High Desert. Centuries later, in the early twentieth century, Portland lawyer and artist C.E.S. Wood and American painter Childe Hassam traveled to the large Double O Ranch near Harney Lake, owned by Wood's friend William Hanley. They set up their easels en plein aire and captured images of the desert's endless sagebrush and its cloud-studded skies. Other well-known Oregon artists, including Charles Heaney, drew on the region's landscape for inspiration.

Part of the New West

Although many residents of the High Desert tend to think of themselves as rugged individualists, their creed of self-reliance is a selective one. Federal and state tax-funded projects in the region’s three main counties since the mid-twentieth century have been granted in much larger per-capita amounts than the tax dollars returned to other parts of the state. Would-be Sagebrush Rebels would find it difficult to meet the basic infrastructure and educational needs of the area without the assistance of the federal government. As in many of the nation’s rural areas, the population of the Oregon High Desert is an aging one, with many residents retired and living on pensions.

Somewhat like the California-based cattle barons of the late nineteenth century, absentee ownership of the area’s larger ranches—for example, Lake County’s ZX Ranch and Harney County’s Roaring Springs Ranch—has become a common practice. And the number of Hispanic residents has increased considerably, particularly in places like Lakeview and Burns, where ranch, farm, and service work provide low-wage jobs.

The Oregon High Desert—now called Oregon’s Outback by promoters—is increasingly a recreational colony of the urbanized, cosmopolitan New West. Hunters still visit each fall from the Willamette and Rogue Valleys with tags for pronghorns and mule-deer bucks. And new kinds of visitors—including long-distance Desert Trail hikers, mountain bikers, birders, and heritage tourists—arrive in larger numbers each year at places such as Steens and Hart Mountains.

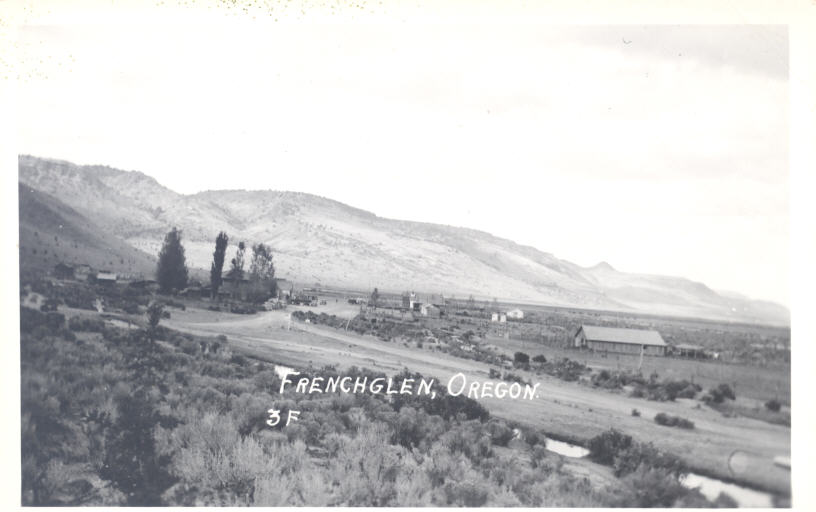

Other tourist attractions include the modest development at Summer Lake Hot Springs, which was nearly abandoned to the elements and is now a favorite camping spot for families. Oregon's state parks system acquired and restored the old cowboy hotel at Frenchglen near Steens Mountain. Under lease to a private operator, the historic Frenchglen Hotel (built in 1916) has become a popular destination, as has the Hotel Diamond (built in 1898), located in nearby ranching town of Diamond. Other amenities continue to proliferate, even in the most remote corners of the region such as in the tiny Lake County town of Paisley. Beneath this veneer of twenty-first-century tourism, however, the High Desert remains a rugged, sparsely populated landscape—Oregon’s empty quarter. For Oregonians, the High Desert remains a distinctive region, truly a place apart.

-

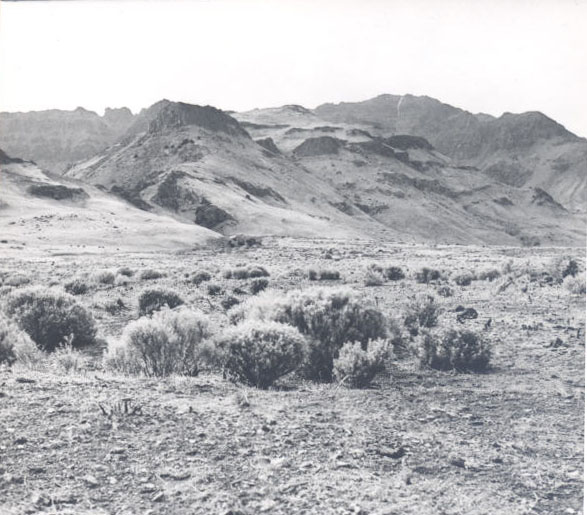

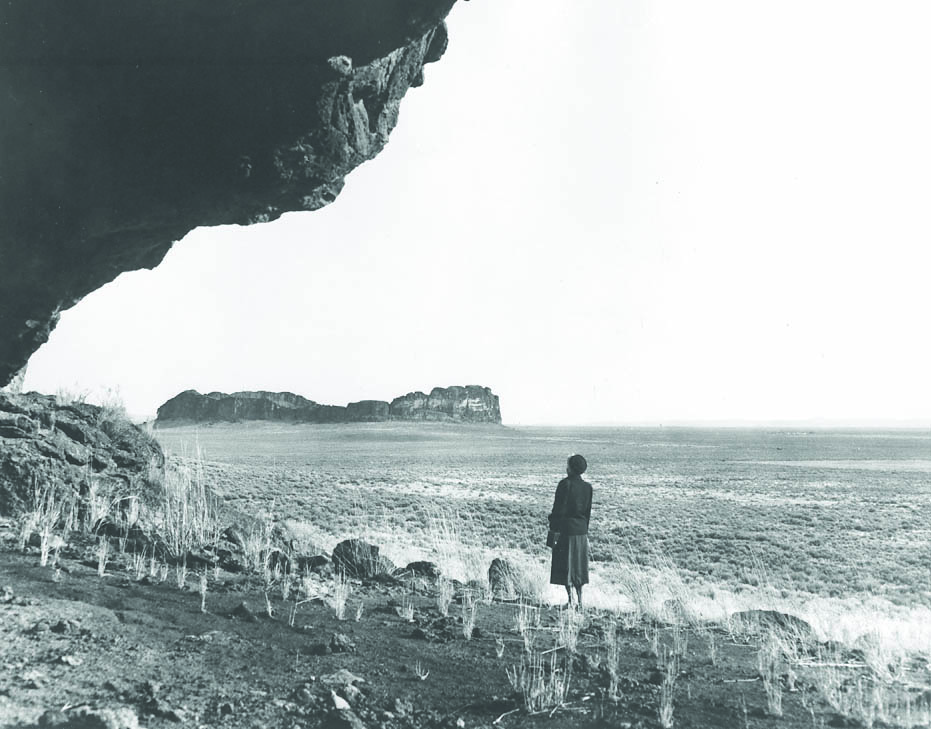

![Alvord Valley, Steens Mountains, 1932]()

Alvord Valley, Steens Mountains, 1932.

Alvord Valley, Steens Mountains, 1932 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., neg. no.004782

-

![Pronghorn antelope in Catlow Valley.]()

Catlow Valley, antelope.

Pronghorn antelope in Catlow Valley. U.S. Bureau of Land Mgmt., Burns Distr., Burnscd2L-039

-

![]()

Artist Charles Edward Heaney (1897-1981).

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, bb003562

-

![Peter Skene Ogden]()

Peter Skene Ogden.

Peter Skene Ogden Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi707

-

![Sketch of Sarah Winnemucca by artist Dave Rock in 1977.]()

Sarah Winnemucca.

Sketch of Sarah Winnemucca by artist Dave Rock in 1977. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Mss 5141-23

Related Entries

-

![Abert Rim]()

Abert Rim

Abert Rim rises from the desert floor in southern Lake County like a gi…

-

![Alvord Desert]()

Alvord Desert

The Alvord Desert, east of the Pueblo Mountains and Steens Mountain and…

-

![Catlow Valley]()

Catlow Valley

Catlow Valley, named for nineteenth-century cattle rancher John Catlow,…

-

![C.E.S. Wood (1852-1944)]()

C.E.S. Wood (1852-1944)

C.E.S. Wood may have been the most influential cultural figure in Portl…

-

![Charles Edward Heaney (1897-1981)]()

Charles Edward Heaney (1897-1981)

Charles Heaney was a printmaker and painter in Oregon for nearly sixty …

-

![Childe Hassam (1859 - 1935)]()

Childe Hassam (1859 - 1935)

Childe Hassam, though not an Oregonian, created some of the best-known …

-

![Crooked River]()

Crooked River

The Crooked River Basin lies in the heart of central Oregon, east of th…

-

![Fort Rock Cave]()

Fort Rock Cave

Fort Rock Cave is located in a small volcanic butte approximately half …

-

![Fort Rock Sandals]()

Fort Rock Sandals

Fort Rock sandals are a distinctive type of ancient fiber footwear foun…

-

![Frenchglen Hotel]()

Frenchglen Hotel

Frenchglen is a small desert community sixty miles south of Burns whose…

-

![Harold Lenoir Davis (1894-1960)]()

Harold Lenoir Davis (1894-1960)

Born and raised in rural and small-town Oregon, Harold Lenoir Davis was…

-

![Owyhee Canyonlands]()

Owyhee Canyonlands

Situated in the far southeastern corner of Oregon, the Owyhee Canyonlan…

-

![Owyhee River]()

Owyhee River

The Owyhee River, in the southeastern corner of Oregon, is a 280-mile-l…

-

![Paisley Caves]()

Paisley Caves

The Paisley Caves—more formally known as Paisley Five Mile Caves—in sou…

-

![Peter French Round Barn]()

Peter French Round Barn

Standing clear on a low rise in a sagebrush-dotted expanse of the easte…

-

![Peter Skene Ogden (1790-1854)]()

Peter Skene Ogden (1790-1854)

More than any other figure during the years of the Pacific Northwest's …

-

![Pleistocene Pluvial Lakes]()

Pleistocene Pluvial Lakes

During the Last Glacial Maximum, from about 24,000 to about 18,000 year…

-

![Reub Long (1898-1974)]()

Reub Long (1898-1974)

A generation after his death in 1974, Reuban A. "Reub" Long still figur…

-

![William Hanley (1861-1935)]()

William Hanley (1861-1935)

William Hanley, who was known as the Sage of Harney Valley, was born on…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Aikens, C. Melvin. Archaeology of Oregon. Portland, Ore.: U.S. Bureau of Land Management, 1986.

Allen, Barbara. Homesteading the High Desert. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1987.

Cox, Thomas R. The Other Oregon: People, Environment, and History East of the Cascades. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2019.

Grayson, Donald K. The Desert’s Past: A Natural History of the Great Basin. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1993.

Hatton, Raymond R. High Desert of Central Oregon. Portland, Ore.: Binfords and Mort, 1977.

Igler, David. Industrial Cowboys: Miller & Lux and the Transformation of the Far West, 1850-1920. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

Jackman, E.R., and R.A. Long. The Oregon Desert. Caldwell, Id.: Caxton Printers, 1964.

Oliphant, J. Orin. On the Cattle Ranges of the Oregon Country. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1968.

Simpson, Peter K. The Community of Cattlemen: A Social History of the Cattle Industry in Southeastern Oregon, 1869-1912. Moscow: University of Idaho Press, 1987.

St. John, Alan D. Oregon’s Dry Side: Exploring East of the Cascade Crest. Portland: Timber Press, 2007.