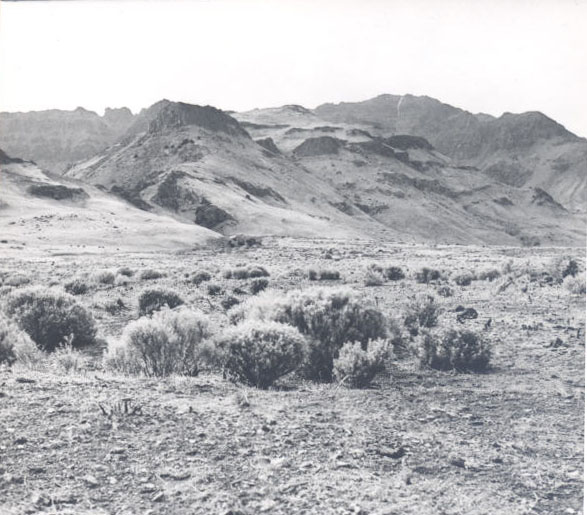

Warner Valley, in southeastern Oregon, is a place of expansive and unspoiled vistas, brilliant sunrises and sunsets, and some of the darkest skies in the United States. The valley is among the earliest-known inhabited places in the state. Obsidian and shell tools and ornaments indicate that Indigenous people in Warner Valley were connected to groups in other parts of present-day Oregon, Nevada, and California as early as 13,000 years ago. Nineteenth-century Euro-American ranchers and settlers were also part of broader social and economic networks in the region. Today, much of the valley is administered by the Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and many people visit the valley for recreational opportunities, including hunting, fishing, wildlife viewing, and camping.

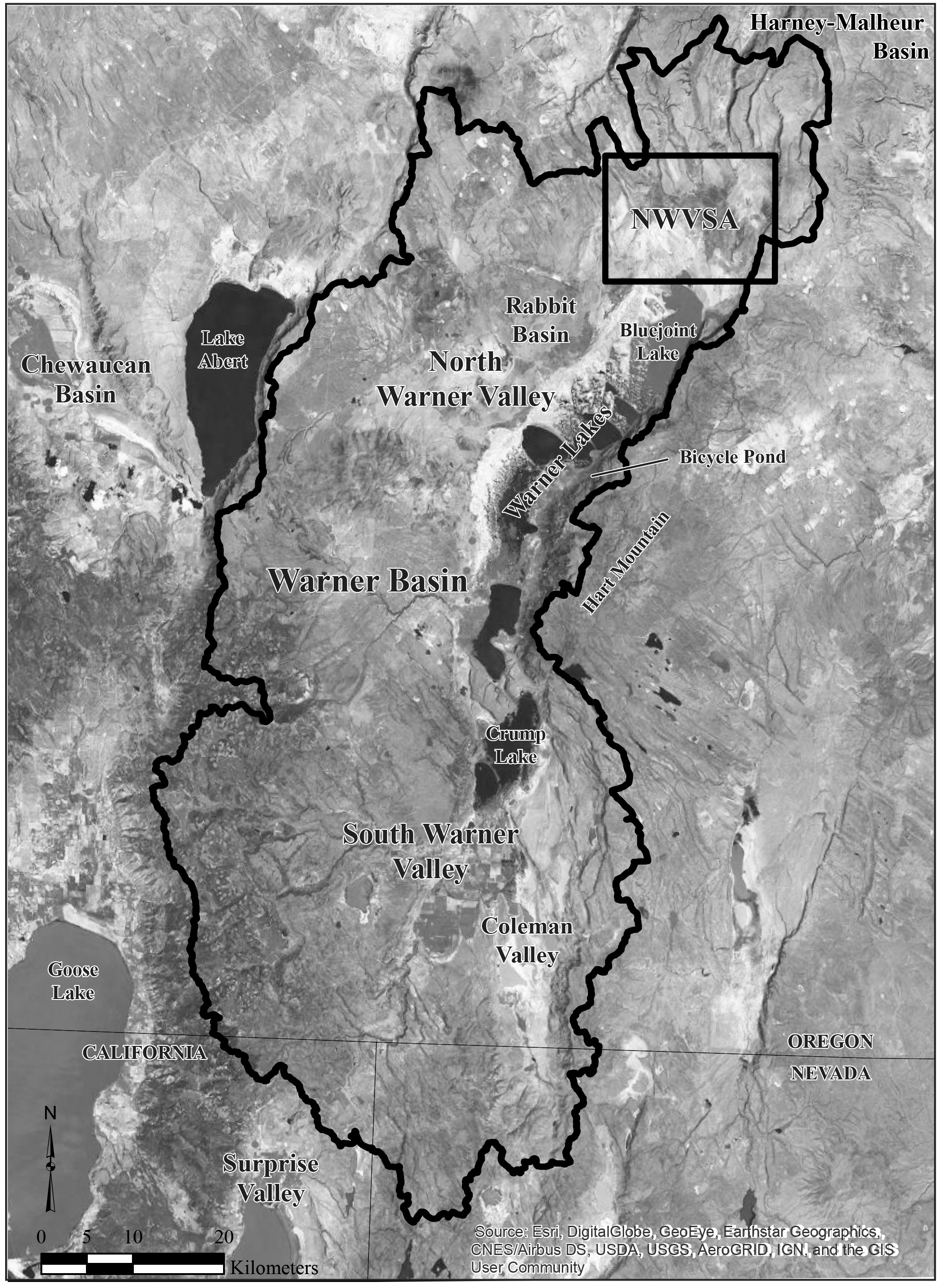

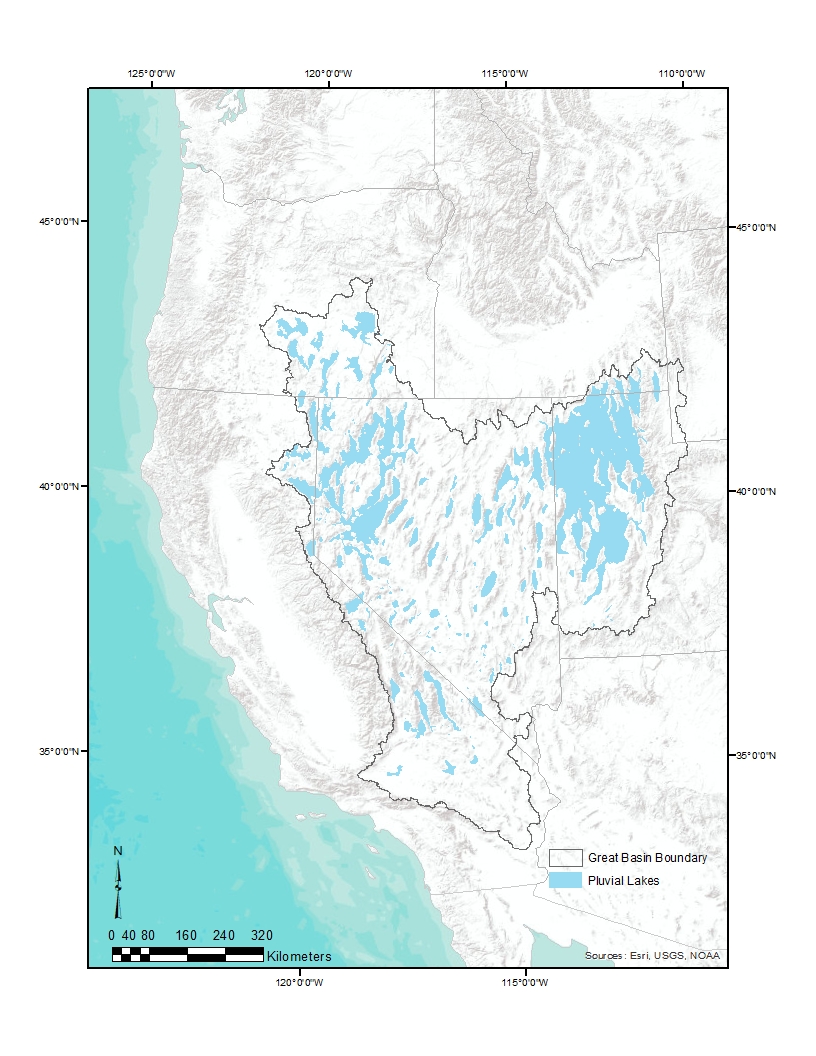

Measuring 85 miles (137 kilometers) north-south by 30 miles (50 kilometers) east-west, Warner Valley was created as the Earth’s crust pulled apart. Hart Mountain and Poker Jim Ridge rise sharply to the east of the valley floor, which is covered today by grasses and shrubs, intermittently wet playas, and the Warner Lakes—a chain of small, shallow lakes connected by sloughs and separated by dunes. In the deeper past, a pluvial lake, Lake Warner, covered much of the valley floor and reached its maximum extent between about 18,340 and 14,385 years ago. Following that highstand, Lake Warner receded rapidly until about 10,300 years ago, after which the Warner Lakes were all that remained of the large lake. During the past 10,300 years, the lakes rose and fell during wet and dry times.

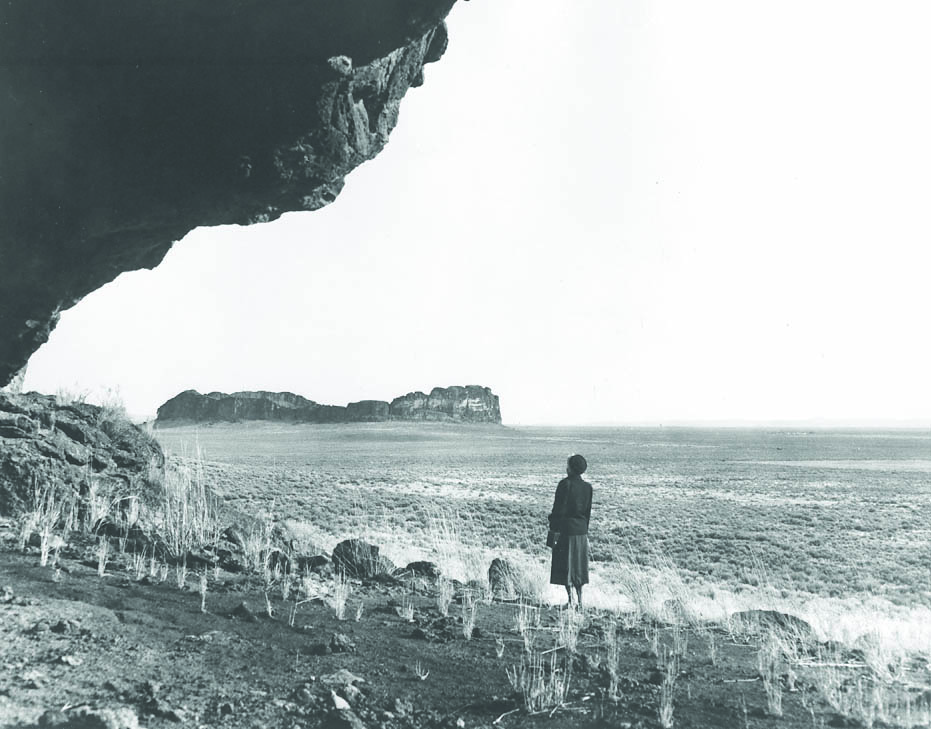

Early populations camped along the shores of Lake Warner beginning 13,000 years ago, and as the lake dried up people moved onto the exposed valley floor. In the northern valley, people congregated to collect rabbits and hares, using large nets as early as about 9,800 years ago. They took their share of the bounty to what is now called the Little Steamboat Point 1 Rockshelter, which overlooks the valley and is where they spent days or weeks processing animals for their meat and fur in preparation for winter. People also visited the rockshelter in the spring, probably to collect edible roots.

Between 9,000 and 5,000 years ago, Warner Valley and the High Desert generally became increasingly hot and dry. The Little Steamboat Point 1 Rockshelter fell into disuse, and surface sites that contain projectile points dating to this period are rare in the area. Human populations likely spent more time in better-watered places such as the Fort Rock Basin or in the surrounding uplands, including Hart Mountain. Rabbits and hares, fish, birds, seeds, and roots remained staple foods.

Beginning about 5,000 years ago, when conditions grew cooler and wetter, the Warner Lakes became centers of activity. Especially after 2,000 years ago, people ranged from their relatively stable residential bases on the lakes to the surrounding basins and adjacent uplands, where they hunted large game, collected rabbits, and harvested plants. They returned to the northern valley and the Little Steamboat Point 1 Rockshelter to process rabbits and hares collected on the valley floor. Visits to the shelter waxed and waned, perhaps in concert with wet and dry periods. After about 1,000 years ago, people ceased visiting the rockshelter, and perhaps the north Warner Valley in general, though the Warner Lakes to the south saw continued use in the centuries leading up to EuroAmerican contact.

EuroAmerican visits to Warner Valley began in the early nineteenth century. Peter Skene Ogden passed through in 1827 with his Hudson's Bay Co. fur brigade, and U.S. military explorer John C. Frémont stopped there in 1843. In 1867, due to perceived threats from Indigenous groups, the U.S. Army established Fort Warner west of the Warner Lakes. The fort was abandoned in 1874, and some of the men stationed there were among the first EuroAmericans to settle in the valley. The settlers obtained lands through the 1850 Swamp Land Act, which granted wetlands to the State of Oregon for sale to private buyers, and through the 1862 Homestead Act. Ultimately, large cattle ranches, including the historic MC Ranch in the southern valley, were established.

Ranching remains a primary way of making a living in the region today, and two unincorporated communities—Plush in the central valley and Adel in the southern valley—are together home to fewer than two hundred people. Both communities offer limited services to those who visit the surrounding areas, including the nearby Hart Mountain National Antelope Refuge.

-

![]()

Steamboat Point, one of several basalt rimrock formations that rise above Warner Valley.

Courtesy University of Nevada Reno, Department of Anthropology

-

![Image shows Warner lakes, sub-basins, and the North Warner Valley Study Area (NWVSA) where the University of Nevada, Reno conducted five years of archaeological fieldwork.]()

Overview of Warner Valley.

Image shows Warner lakes, sub-basins, and the North Warner Valley Study Area (NWVSA) where the University of Nevada, Reno conducted five years of archaeological fieldwork. Courtesy University of Nevada Reno, Department of Anthropology

-

University of Nevada, Reno students begin excavations at the Little Steamboat Point 1 Rockshelter, Summer 2011.

Courtesy University of Nevada Reno, Department of Anthropology

-

![]()

Late Pleistocene fluted (lone example on the left) and stemmed (three examples on the right) projectile points left behind by early visitors to Warner Valley.

Courtesy University of Nevada Reno, Department of Anthropology

Related Entries

-

![Bernard Daly (1858–1920)]()

Bernard Daly (1858–1920)

Bernard Daly did much to improve the lives of Oregonians, particularly …

-

![Camp Harney]()

Camp Harney

From 1867 to 1880, the U.S. Army’s Camp Harney provided a strategic mil…

-

![Catlow Valley]()

Catlow Valley

Catlow Valley, named for nineteenth-century cattle rancher John Catlow,…

-

![Fort Rock Cave]()

Fort Rock Cave

Fort Rock Cave is located in a small volcanic butte approximately half …

-

![Fort Rock Sandals]()

Fort Rock Sandals

Fort Rock sandals are a distinctive type of ancient fiber footwear foun…

-

![Hart Mountain Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) Camp]()

Hart Mountain Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) Camp

Camp Hart Mountain, a Civilian Conservation Corps camp, operated from O…

-

![High Desert]()

High Desert

Oregon’s High Desert is a place apart, an inescapable reality of physic…

-

![Lakeview]()

Lakeview

The City of Lakeview, in northern Goose Lake Valley at an elevation of …

-

![Peter Skene Ogden (1790-1854)]()

Peter Skene Ogden (1790-1854)

More than any other figure during the years of the Pacific Northwest's …

-

![Pleistocene Pluvial Lakes]()

Pleistocene Pluvial Lakes

During the Last Glacial Maximum, from about 24,000 to about 18,000 year…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Jenkins, D. L., T. J. Connolly, and C. M. Aikens, eds. Early and Middle Holocene Archaeology of the Northern Great Basin. University of Oregon Anthropological Papers No. 62. Eugene: University of Oregon, 2004

Kingrey, H. U. "Roots, Rocks, Rabbits: Residue Analysis of Early Holocene Ground Stone from the Little Steamboat Point-1 Rockshelter (35HA3735), Warner Valley, OR." MA thesis, University of Nevada, Reno, 2022

Nicol, D. L., and A. Thompson. Bill Kitt: From Trail Driver to Cowboy Hall of Fame. Caldwell: Caxton Printers, 2009.

Smith, G. M. , ed. In the Shadow of the Steamboat: A Natural and Cultural History of North Warner Valley, Oregon. University of Utah Anthropological Papers No. 137. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2022

Smith, G. M., and P. Barker. "The Terminal Pleistocene/Early Holocene Record in the Northwestern Great Basin: What We Know, What We Don’t Know, and How We May Be Wrong." PaleoAmerica 3.1 (2017): 13–47.

Smith, G. M., D. Duke, D. L. Jenkins, T. Goebel, L. G. Davis, P. O’Grady, D. Stueber, J. E. Pratt, and H. L. Smith. "The Western Stemmed Tradition: Problems and Prospects in Paleoindian Archaeology in the Intermountain West." PaleoAmerica 6.1 (2020): 23–42.

Tipps, J. A. High, Middle, and Low: An Analysis of Resource Zone Relationships in Warner Valley, Oregon. Sundance Archaeological Research Fund Technical Report No. 98–1. Reno: University of Nevada, 1998.

Wriston, T. A., and G. M. Smith. "The History of Lake Warner." In In the Shadow of the Steamboat: A Natural and Cultural History of North Warner Valley, Oregon, edited by G. M. Smith, 20–34. University of Utah Anthropological Papers No. 137. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2022.

Young, D. C. Late Holocene Landscapes and Prehistoric Land Use in Warner Valley, Oregon. Sundance Archaeological Research Fund No. 7. Reno: University of Nevada, 2000.