From 1867 to 1880, the U.S. Army’s Camp Harney provided a strategic military presence in southeast Oregon that—under the auspices of protecting EuroAmerican mining, residents, and transportation—waged war against the Northern Paiute, Modoc, Nez Perce, Bannock, and other tribes during the Indian War era. Located just north of Harney Valley, east of Burns, the camp served as a hub that connected even more remote posts to Portland, The Dalles, and Canyon City by way of the The Dalles–Boise Military Road; to the Willamette Valley by way of the Willamette Valley and Cascade Mountain Military Road; and to the Oregon Central Military Road by way of the military road to Fort McDermit.

At its inception, Camp Harney factored heavily into Colonel George C. Crook’s strategic plan to defeat Northern Paiutes in the conflict known as the Snake War. Concerned that the military posts in southeast Oregon and southwest Idaho were too dispersed, Crook reorganized the region into two military districts and personally selected the site for Camp Harney. The post was established by soldiers from the 23rd U.S. Infantry on August 16, 1867.

Crook originally named the post Camp Steele after General Frederick Steele, who was then commanding the Department of the Columbia; but General Henry Halleck suggested a change to Camp Harney, after the earlier-serving Department of Oregon commander General William S. Harney, to avoid confusion with an existing Camp Steele on Washington State’s San Juan Island. Crook operated out of the post for the next year, until a Paiute peace council led by Weawea and about eight hundred war-weary Paiutes arrived and negotiated surrender.

The post sat in the north end of a larger, 640-acre military reservation created in December 1872, with an adjacent reservation of land for hay and wood. In 1878, the army reported that about eight hundred Paiute lived nearby, and more lived about fifty-five miles to the east at the Malheur Indian Agency. The military reservation sat within the 1.8 million-acre Malheur River Indian Reservation.

Typical of U.S. Army forts of the era, the post featured an open design, without a stockade wall and centered on a parade ground for drilling. By 1877, the post included almost two dozen buildings for its military and civilian employees, laid out in a rectangle that paralleled Rattlesnake Creek. Six officers quarters, four built of logs and two of frame construction, lined the west side of the main parade ground. Along the east side of the parade ground, in front of the post bakery, were three log barracks buildings that housed one infantry and two cavalry companies.

The post headquarters and adjutant’s office capped the parade ground’s north end. Beyond it to the north were the 1867 post hospital (with a new ward with twelve beds built in 1875), a sutler’s store and residence, a commissary storehouse, the quartermaster’s storehouse, an icehouse, and a butchery. The post guardhouse marked the parade ground’s south end, with two frame cavalry stables, six log quarters for married soldiers and laundresses, a grain house, blacksmith and carpenter shops, a small stable, quartermaster’s and hay corrals, and a small sawmill (powered by eight horses) beyond. The post, along with Camp Warner and the Malheur Indian Agency, drew supplies from the farms of the John Day Valley and made “a good market for the farmers of Grant County."

During the post’s active years, companies from five regiments served as its regular garrison: the 23rd, 21st, and 2nd U.S. Infantry and the 8thand 1st U.S. Cavalry. The camp averaged 163 soldiers and officers in garrison during its operation, ranging from a low of 80 in August 1867 to a high of 358 in August 1878. When not on active campaign in the region, soldiers from the post escorted settlers, miners, stagecoaches, and supply wagons; retrieved stolen livestock; constructed camp buildings; and guarded prisoners, primarily Bannock and Paiute. The post also employed dozens of civilian employees, chiefly packers, cargadores (stevedores or porters), teamsters, and craftsmen. Writer Sarah Winnemucca (Paiute) served at the post as a paid translator, facilitating the camp’s communication with local tribes.

The camp served again as a center of operations during the Bannock War of 1878, and there the army imprisoned over five hundred Paiutes and Bannocks. In 1879, the name was changed to Fort Harney, but it was to be short-lived. The army’s forcible resettlement of the fort’s prisoners to the Yakima Reservation and the closure of the Malheur Reservation that same year rendered the fort obsolete. As a result, General Oliver O. Howard, familiar with the fort after visits in 1874 and 1878, ordered its closure, and the last soldiers departed in June 1880.

Fort Harney’s grounds were returned to the public domain in 1889, and many of its structures were reused by local settlers. No buildings now remain, and the site is primarily on private land. An Oregon History informational sign at the intersection of state highway 20 and county road 102 interprets the site.

-

![]()

Camp Harney, 1872.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 1682, photo file 405

-

![]()

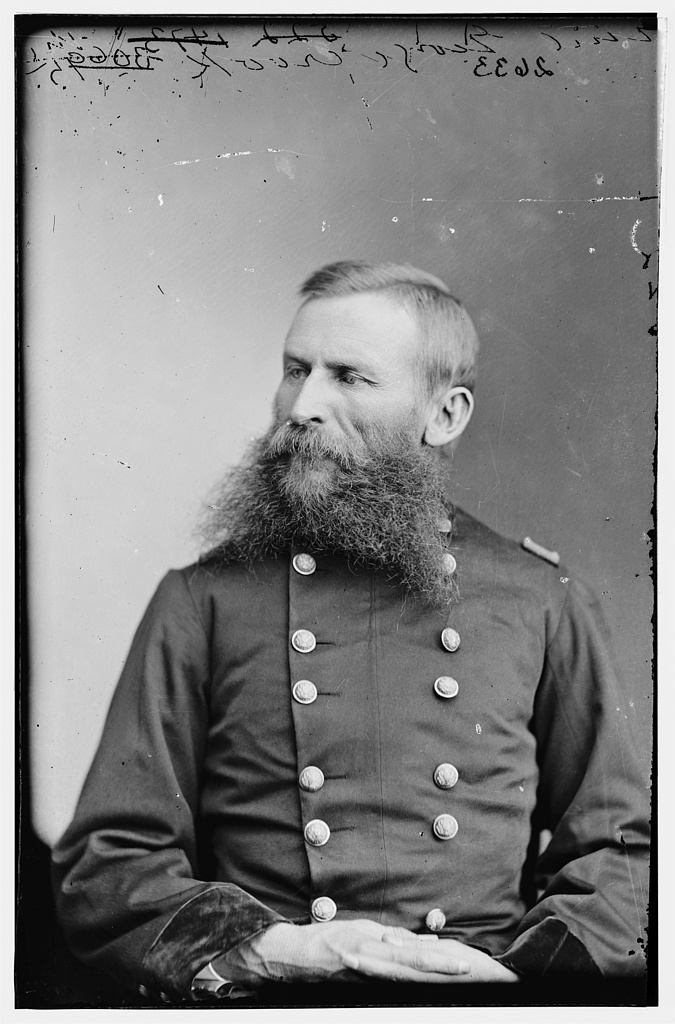

George C. Crook.

Courtesy Library of Congress, LC-DIG-cwpbh-04032

-

![]()

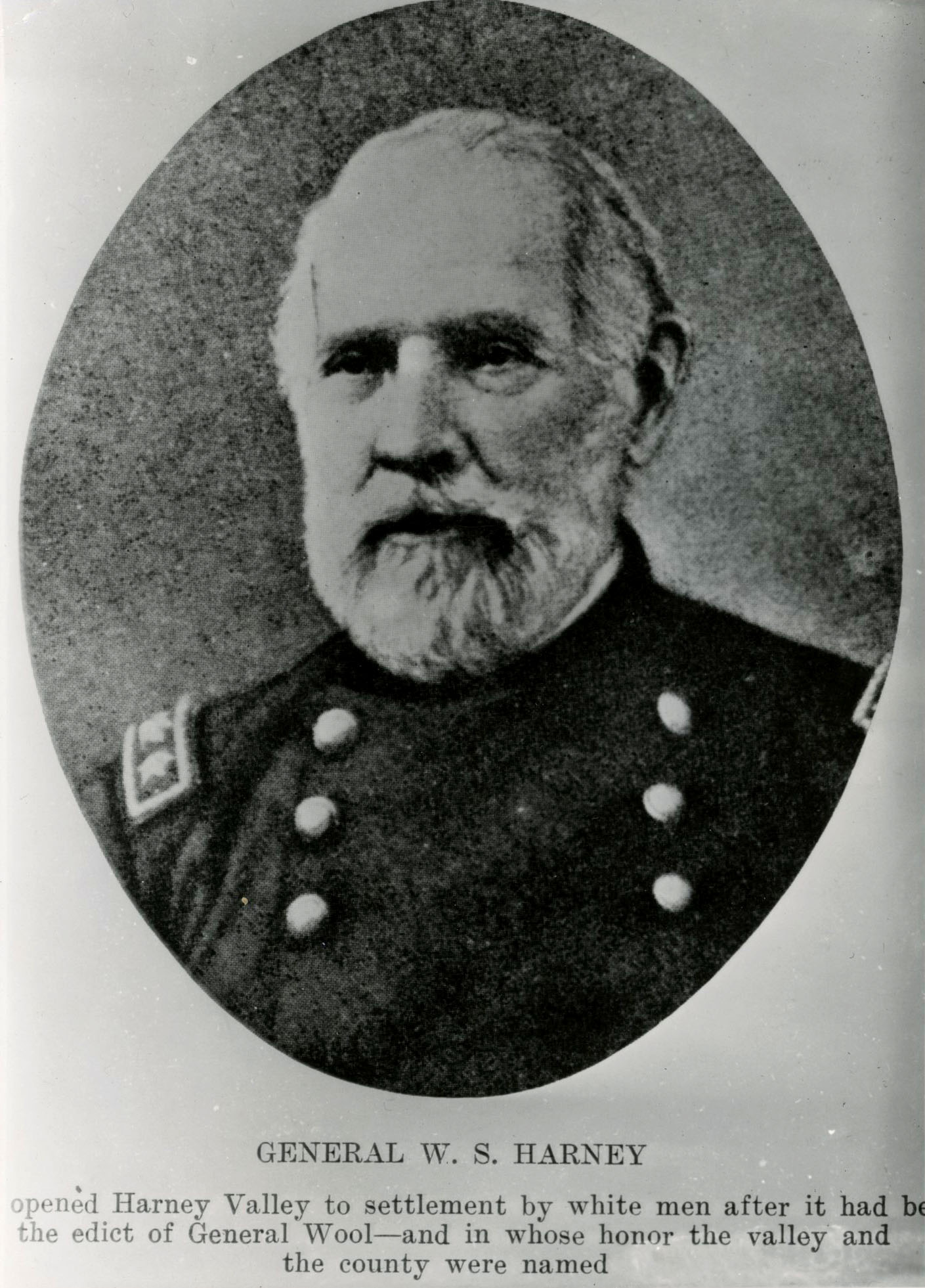

William S. Harney.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi4396

-

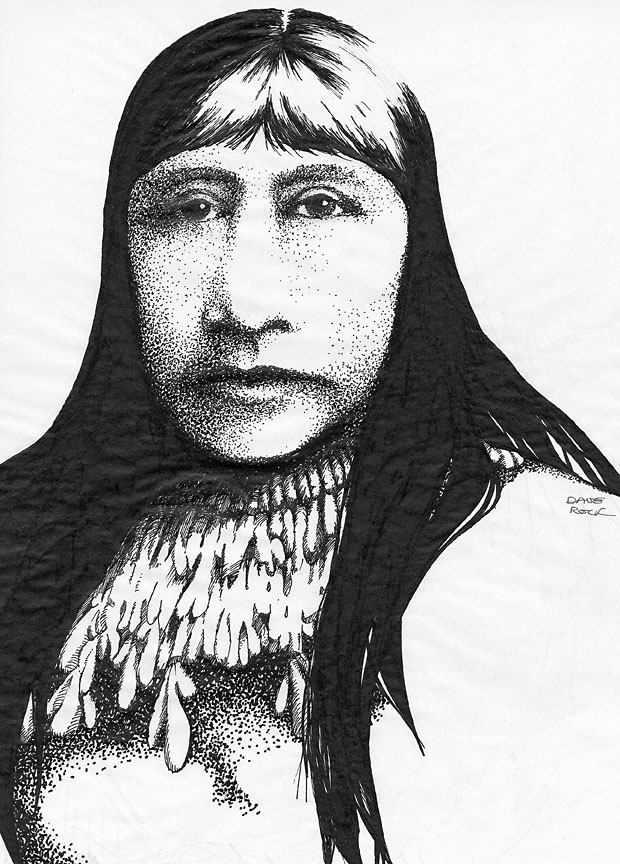

![Sketch of Sarah Winnemucca by artist Dave Rock in 1977.]()

Sarah Winnemucca.

Sketch of Sarah Winnemucca by artist Dave Rock in 1977. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Mss 5141-23

Related Entries

-

![Sarah Winnemucca (1844?-1891)]()

Sarah Winnemucca (1844?-1891)

Sarah Winnemucca, a Paiute, had a clear purpose in life: “I mean to fig…

-

![William Selby Harney (1800-1889)]()

William Selby Harney (1800-1889)

A brash, opportunistic cavalry officer with an explosive temper and a v…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Cozzens, Peter. Eyewitness to the Indian Wars, 1865-1890, Volume 2:The Wars for the Pacific Northwest. Mechanicsburg, Penn.: Stackpole Books, 2002.

Magrid, Paul. The Gray Fox: George Crook and the Indian Wars. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2011.

Michno, Gregory. The Deadliest Indian War in the West: The Snake Conflict, 1864-1868. Caldwell, ID: Caxton Press, 2007.

United States, Army. Post Returns, Camp Harney. August 1867 to June 1880.

_____, Military Division of the Pacific. Outline Descriptions of Military Posts in the Military Division of the Pacific. San Francisco: U.S. Army, 1879.

Robert M. Utley. Frontier Regulars: The United States Army and the Indian, 1866-1891. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1973.