Introduction

In popular culture, the Oregon Trail is perhaps the most iconic subject in the larger history of Oregon. It adorns a recent Oregon highway license plate, is an obligatory reference in the resettlement of Oregon, and has long attracted study, commemoration, and celebration as a foundational event in the state’s past. The Oregon Trail was first written about by an American historian in 1849, while it was in active use by migrants, and it subsequently was the subject of thousands of books, articles, movies, plays, poems, and songs. The trail continues as the principal interest of a modern-day organization—the Oregon-California Trails Association—and of major museums in Oregon, Idaho, and Nebraska.

The Oregon Trail has attracted such interest because it is the central feature of one of the largest mass migrations of people in American history. Between 1840 and 1860, from 300,000 to 400,000 travelers used the 2,000-mile overland route to reach Willamette Valley, Puget Sound, Utah, and California destinations. The journey took up to six months, with wagons making between ten and twenty miles per day of travel. The trail followed the Missouri and Platte Rivers west through present-day Nebraska to South Pass on the Continental Divide in Wyoming, then west along the Snake River to Fort Hall in eastern Idaho, where travelers typically chose to continue due west to Oregon or to head southwest to Utah and California.

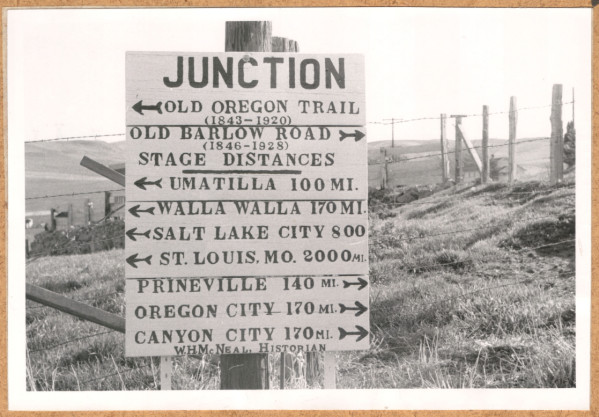

In Oregon, the trail passed through the Powder River and Grande Ronde Valleys, over the Blue Mountains, and down the Columbia River to The Dalles, where many rafted their wagons and belongings to the lower Columbia River Valley. After 1846, travelers could make their way overland on the Barlow Road from The Dalles, around Mount Hood, and directly to Oregon City on the Willamette River.

Families and individuals on the trail typically traveled in companies that had twenty-five or more wagons, with one or more individuals providing general leadership. When smaller groups combined, leaders shared duties and the authority for keeping order. Travelers generally walked alongside wagons full of their belongings and foodstuffs. Most used farm wagons that had been modified for long-distance travel, including strengthened axle trees and wagon tongues and wooden bows that arched over the wagon box to support canvas or other heavy cloth covering.

The wagons were ten to twelve feet long, four feet wide, and two to three feet deep, with fifty-inch diameter rear wheels and forty-four-inch front wheels made of oak with iron tire rims. The wagons weighed from 1,000 to 1,400 pounds and carried loads between 1,500 and 2,500 pounds. They had sturdy hardwood box frames that were made as watertight as possible to facilitate stream and river crossings. Most overlanders used two or four yoked oxen to pull their wagons, because they had more endurance and were less expensive than horses or mules and they were less likely to be stolen by Indians. Prudent travelers carried spare parts, grease for axle bearings, heavy rope, chains, and pulleys to keep wagons repaired and to aid in rescue from predicaments.

Background

From the earliest decades of the Republic, groups of migrants headed west from the established states to stake out homesteads on the western periphery of institutional society. They traveled first across the Appalachian Mountains into the Old Northwest—today’s states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan—then from the South to populate Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Missouri, and Iowa. By the 1820s, some politicians called for resettlement in the Oregon Country, a relatively un-resettled region over which the United States and Great Britain jointly claimed sovereignty by treaty in 1818. The penetration of the fur trade into the region during the 1820s and 1830s, especially on the Upper Missouri and the Columbia river basins, exposed both the natural wealth of the region and the presence of Native populations. During most of this westward movement, overland trails and river passages were essential conduits of people, trade, and institutional expansion.

Long-distance wagon travel had long moved Americans west and south on such trails as the Great Wagon Road in the 1720s, the Wilderness Road in the 1770s, the Natchez Trace in the 1810s, and the Santa Fe Trail in the 1820s. But the Oregon Trail is foremost as the longest and most heavily used route in the nation’s resettlement of western North America.

The Oregon Trail developed from the discovery in 1812 of a wagon-safe route over the Continental Divide at South Pass in present-day Wyoming by Robert Stuart, a Pacific Fur Company man returning from Fort Astor. Stuart had gone east from the Columbia, traversing the Blue Mountains, ascending the Snake River in present-day Idaho, and veering south to South Pass and down the Platte River to the Missouri. His route meant, as the Missouri Gazette predicted in 1813, that “a journey to the Western Sea will not be considered (within a few years) of much greater importance than a trip to New York.”

Fur trader William Sublette made one of the first widely reported wagon trips from South Pass to St. Louis in 1830, and missionaries trekked over western sections of the future Oregon Trail several years later on their way to the Columbia and Willamette Valleys. In the late 1830s, the Oregon Provisional Emigration Society, a Methodist group based in Massachusetts, promoted missionary expeditions to Oregon. Some missionaries, who had been sent west by the American Board of Foreign Missions, praised the Oregon Country’s climate and fertile landscape in letters published in eastern newspapers.

Hall Kelley’s General Circular for prospective emigrants (1831), Thomas Farnham’s Travels in the Western Prairies (1843), poor economic conditions in the Mississippi Valley, and episodic outbreaks of disease prompted thousands to take a chance on emigration to Oregon. By the early 1840s, the willing and determined, captured by the idea of Oregon, decided to ignore the naysayers and embrace the adventure. They took the risks, as the saying went, “to see the elephant,” a nineteenth-century phrase that meant enduring hardships to experience the unbelievable.

By the mid-1840s, emigrants could use trail guides to plan their journey and avoid common mistakes. Lansford Hastings’s Emigrant Guide to Oregon and California (1845), Overton Johnson’s Route Across the Rocky Mountains (1846), and Joel Palmer’s Journal of Travels (1847) were popular and widely distributed accounts of travel on the Oregon Trail.

Setting Off

Travel west on the Oregon Trail began at several towns on the Missouri River, from Independence to Council Bluffs, and then followed routes west on both sides of the Platte River. Companies of wagons formed, emigrants purchased supplies, and the group followed the developing ruts west. James Miller’s 1848 diary entry describes a typical small company: “We had our outfit, teams [three wagons, two ox teams, one horse team] and necessary provisions for the trip, which consisted of 200 pounds of flour for each person (10 of us), 100 pounds of bacon for each person, a proportion of corn meal, dried apples and peaches, beans, salt, pepper, rice, tea, coffee, sugar and many smaller articles for such a trip; also a medicine chest, plenty of caps, powder and lead. Our company was made up of David O'Neill, one wagon, two boys; two Catholic priests [Rev. J. Lionet and Fr. Lampfrit] and their servant; David Huntington and wife, three children; David Stone and wife, two children; George Hedger and William Smith, George A. Barnes and wife, L.D. Purdeau, Lawrence Burns, James Costello, Jacob Conser and wife, two children; George Wallace, Joseph Miller and wife, three sons and daughter.”

Most groups tried to set out by mid-April. Their goal was to reach Fort Kearny, founded in 1848 near present-day Kearny, Nebraska, by May 15; Fort Laramie in present-day Wyoming by mid-June; South Pass on the Fourth of July; and Oregon by mid-September. Wagon trains could average from twelve to fifteen miles per travel day, but most had to pause because of conditions and some did not travel on Sundays. In many sections, the trail spread across miles of terrain, as successive emigrants sought easier transit. Sources of water and forage for animals often determined camping locations.

Stream and river crossings, steep descents and ascents, violent storms, and the persistent threat of disease among large groups of travelers were the most common challenges. Disease was the greatest threat on the trail, especially cholera, which struck wagon trains in years of heavy travel. Most deaths from disease occurred east of Fort Laramie. Accidents were the second most frequent cause of death on the trail. Indians killed about 400 emigrants before 1860, but emigrants killed more Indians, and no Indians or emigrants died from violence until 1845.

Wagon trains organized their members through consensual agreement to rules of order, behavior, property security, and work responsibilities written into constitutions that also identified officers and their specific duties. Constitutions and bylaws prevailed until 1850, after which most groups preferred to operate using ad hoc agreements. Many wagon trains organized tribunals to mete out punishments for property crimes, assaults, and activities that jeopardized security. The most common punishments were assignment of extra guard duty and expulsion. Whippings were rare, and executions took place only after a legal proceeding and a jury verdict.

African Americans traveled the Oregon Trail, making up perhaps as many as three percent of overlanders before 1860. Some traveled as the slave property of white travelers, but many were free people. George Bush, for example, traveled in the Simmons-Gilliam wagon train in 1844 as a free man, hiding some $2,000 in silver coins, which he loaned to cash-strapped travelers. For many free Blacks, emigration west offered hope for a better life with fewer social obstacles, and in many cases that proved to be true.

The trail experience for men and women differed considerably. Their roles and duties followed nineteenth-century norms, with women responsible for children, cooking, laundry, and personal gear. Women walked, as did men, but they did not stand guard and were not expected to work ox teams or repair wagons. Men held most, if not all, leadership positions.

The Trail in Oregon

By the time overlanders reached the Oregon Country in present-day southeastern Idaho, they had traveled nearly two-thirds of their journey, but the most difficult sections lay ahead. At Fort Boise, established by the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1834 at the confluence of the Owyhee and Snake Rivers, the trail crossed the Snake at a wagon ford 400 hundred yards downstream from the fort. Overlanders continued northwest, crossing the Malheur River and leaving the Snake at a place known as Farewell Bend before climbing up the Burnt and Powder river drainages to Ladd Canyon. The trail then dropped steeply to the Grand Ronde River and ascended the east slope of the Blue Mountains to Emigrant Springs.

From Emigrant Springs, the Oregon Trail proceeded through Deadman Pass (named during the 1870s), which was a key opening to the Umatilla River Valley. Just east of present-day Pendleton, a branch of the trail headed north to Waiilatpu, a mission established by Marcus and Narcissa Whitman in 1836, and then west on the Walla Walla River to Fort Walla Walla, a post first established by the North West Fur Company in 1818. The main route crossed the Umatilla River near present-day Echo, Oregon, and headed west on the south side of the Columbia River to an easy ford on the John Day River near present-day Blalock Canyon. Travelers got their first view of the Columbia River from the benchlands above present-day Biggs. They then descended to river level and proceeded west to the mouth of Deschutes River, where the crossing was often perilous.

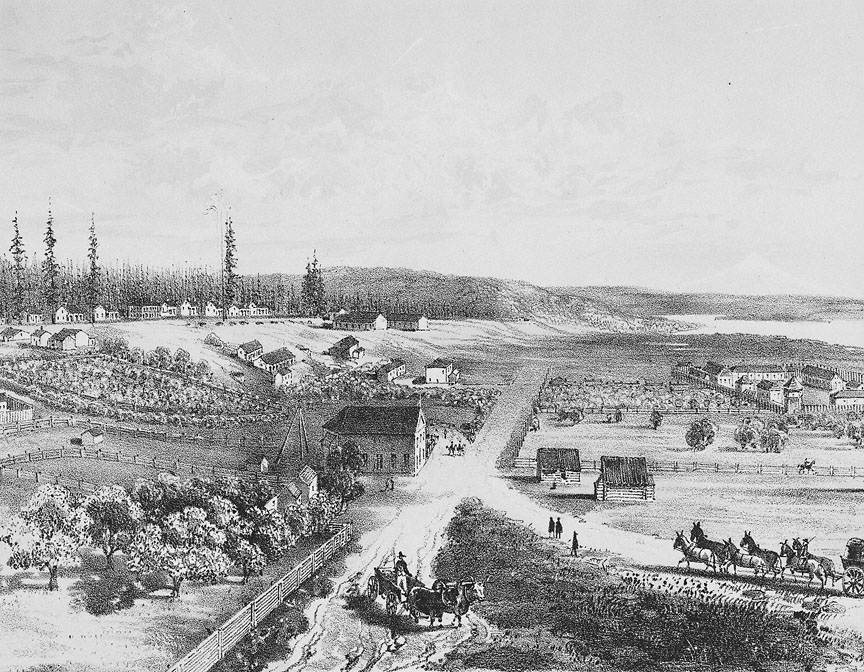

Overlanders struck their first EuroAmerican settlement in Oregon at The Dalles, where they found houses, a schoolhouse, a barn, and cultivated fields, all part of a mission that Methodists had established in 1838. Until 1846, travelers had only one choice: to break down their wagons and load them on rafts to float down the turbulent Columbia River. It was risky, and passage was expensive; many had to borrow to pay for downriver passage.

By 1846, however, travelers had another option. Samuel K. Barlow and Joel Palmer pioneered a route around the south flank of Mount Hood to Oregon City in the lower Willamette Valley, and Barlow developed the route into a rough toll road. The Barlow Road initially cost five dollars per wagon and ten cents per head of stock. The road stretched from The Dalles to Oregon City and operated well into the twentieth century, when it was donated to public use. Portions of present-day U.S. Highway 26 and Oregon Highways 211 and 224 on the west side of Mount Hood follow parts of the Barlow Road.

Other alternative routes developed, often called cutoffs, across Oregon to the Willamette Valley. The same year that Barlow and Palmer traced the road around Mount Hood, a group of emigrants set off on what became known as the Meek Cutoff, which mountain man Stephen Meek promised would shorten the trip by 150 miles. In late August, 1,000 overlanders in at least 200 wagons followed Meek on a trail that began directly west of Fort Boise. He soon lost his way and jeopardized the travelers, who split up into separate groups on the Snake River near present-day Ontario and eventually made their way to The Dalles in early October, at about the time Barlow and Palmer headed around Mount Hood. At least twenty-four people died.

In 1846, Jesse and Lindsay Applegate laid out a southern route that took overlanders from Fort Hall on the Snake River, southwest along the upper Humboldt River, across present-day Nevada and California to Klamath Lake and northwest to the southern Willamette Valley. Although the route was never as heavily used as the Barlow Road, the Applegate Trail led thousands of people to Oregon.

Another splinter trail developed north of the Columbia River, where overlanders arrived at Fort Vancouver after descending the river from The Dalles and taking advantage of Hudson’s Bay Company posts. Michael Simmons, founder of Tumwater in 1845; John Jackson, an 1844 EuroAmerican settler on the Cowlitz River; and Peter Crawford, founder of Kelso in 1847, began settlements along an overland and river trail north to Puget Sound. Simmons chose to head north, because George Bush, an African American, was part of his wagon train and the Oregon Provisional Legislature had outlawed Black resettlement in Oregon. Within a few years of his decision to go north, in 1853, Simmons was part of a political movement that split off Washington Territory from Oregon.

Emigrant relations with Native peoples in the Oregon Country differed considerably from encounters on the Great Platte River Road. There were more meetings between Indians and overlanders west of the Continental Divide; and of the famous incidents of Indian depredation, most occurred west of Fort Hall. Nonetheless, the great majority of the encounters between Indians and emigrants was peaceful, and many Indians benefitted the travelers. In the Grand Ronde and Umatilla Valleys, for example, Indian families often sold produce to emigrants. In early September 1853, Rebecca Ketcham noted in her journal: “There are some traders and plenty of Indians here, the Nez Perces. Mr. Gray recognized a good many of them, some of them him. They were all on horses. Bought some potatoes of them, enough for dinner…also some dry peas.” Along the route, Indians took advantage of stream crossings and other places to aid emigrants to extract payment for their services, which some emigrants grumbled about, but paid willingly. As more and more emigrants crossed Indian lands during the 1840s and early 1850s, Native people understandably became more resistant to the invading resettlers.

Consequences

The first Oregon Trail emigrants to reach Oregon followed in wake of earlier agriculturalists, retired Hudson’s Bay Company employees who had settled out in the lush Willamette Valley. “The land itself,” an early emigrant wrote home, “cannot be excelled anywhere in the world in fertility and productivity, for everything one plants grows luxuriantly and abundantly.” Low-cost homestead lands became a prime draw for Oregon Trail migrants after the Oregon Provisional Legislature passed a liberal land law in July 1843 that secured 640 acres for an emigrant family. The 1843 arrivals bolstered the provisional government with their support in the 1845 revisions of the Organic Law land law that created a House of Representatives with the power to pass statutes.

Continued emigration added sufficient population by 1846 to aid U.S. negotiators in securing the Oregon Treaty with Great Britain, which described Oregon as the land north of the 42nd Parallel, east to the Continental Divide, and north to the 49th Parallel. With just over 5,000 inhabitants, Oregon secured territorial status from Congress in 1848, and the territory’s population topped 12,000 by 1850.

In 1850, Congress affirmed Oregon’s extraordinary land law as the Oregon Donation Land Act, which extended the provisions until 1855 and resulted in 7,500 claims to more than 2.5 million acres. The enormous influx of overland emigrants and liberal land laws caused the U.S. government to purchase, through treaties, millions of acres of land from Native people. The treaties, negotiated by Isaac Stevens and Joel Palmer in 1854-1855, secured most tribal land in the states of Oregon and Washington.

Not long after Oregon achieved statehood in 1859, veterans of the Oregon Trail migration realized the historic importance of their journey and resettlement of the state. Founded in 1874, the Oregon Pioneer Association held annual meetings, published memoirs of their trail experiences, and sought to document and preserve details of the emigration. The meetings led to the creation by state charter of the Oregon Historical Society in 1898, a private corporation charged with preserving Oregon historical objects and promoting study of the state’s past. Among the early memoirs published by the Oregon Historical Society was Jesse Applegate’s “A Day with the Cow Column in 1843” in 1900, one of the most reprinted Oregon Trail narratives. The enthusiasm for the Oregon Trail as a state icon prompted 1852 trail emigrant Ezra Meeker to retrace his route west in reverse, driving his ox-drawn wagon from Olympia, Washington, to Iowa in 1906 and again in 1911 to promote the preservation of Oregon Trail sites and history.

In 1923, Walter Meacham, an Oregon Trail enthusiast from Baker, created the Old Oregon Trail Association, which staged sentimental public programs promoting the commemoration of nineteenth-century emigration to Oregon. The National Park Service declared the Oregon Trail a National Historic Trail in 1978, partly in anticipation of the trail’s sesquicentennial. In 1993, the State of Oregon, through the Oregon Trail Coordinating Committee, sponsored a multi-year commemoration with public programs, publications, and museum exhibitions.

By the 1990s, several museums on the Oregon Trail had opened in Oregon. The Flagstaff Hill/National Oregon Trail Interpretive Center in Baker City, operated by the Bureau of Land Management, opened in 1992. In 1995, the Confederated Tribes of Umatilla Indian Reservation dedicated Tamástslikt Cultural Institute, the only Native American museum on the trail. Clackamas County created the End of the Trail Interpretive Center in Oregon City, and the Columbia River Gorge Discovery Center in The Dalles opened in 1997 as part of the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area.

Interest in the Oregon Trail continues to generate state, regional, national, and international interest. Books, articles, and ephemera publications document new findings and reprint diaries, memoirs, and descriptions of the trail and travel conditions. Today’s tourists can see evidence of the trail in wagon ruts preserved on the landscape in many locations. As an icon of Oregon history, the Oregon Trail is likely to endure in scholarship and in heritage commemorations.

-

![Pamphlets like these both encouraged and guided emigrants to resettle in the West.]()

"Where to Emigrate and Why," by Frederick Goddard, 1869.

Pamphlets like these both encouraged and guided emigrants to resettle in the West. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi8798

-

![An Old Oregon Trail marker in La Grande, dedicated on October 27, 1907. George Himes from the Oregon Historical Society is seated second from the right.]()

Oregon Trail marker, La Grande, 1907.

An Old Oregon Trail marker in La Grande, dedicated on October 27, 1907. George Himes from the Oregon Historical Society is seated second from the right. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library

-

![Illustration by Emma H Adams.]()

Emigrants Crossing the Mountains, 1888.

Illustration by Emma H Adams. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, 88287

-

![Illustration of one of the many trail hazards: mud. Artist was George H. Baker, and his drawings appeared in Crossing the Plains, by J.M. Hutchings.]()

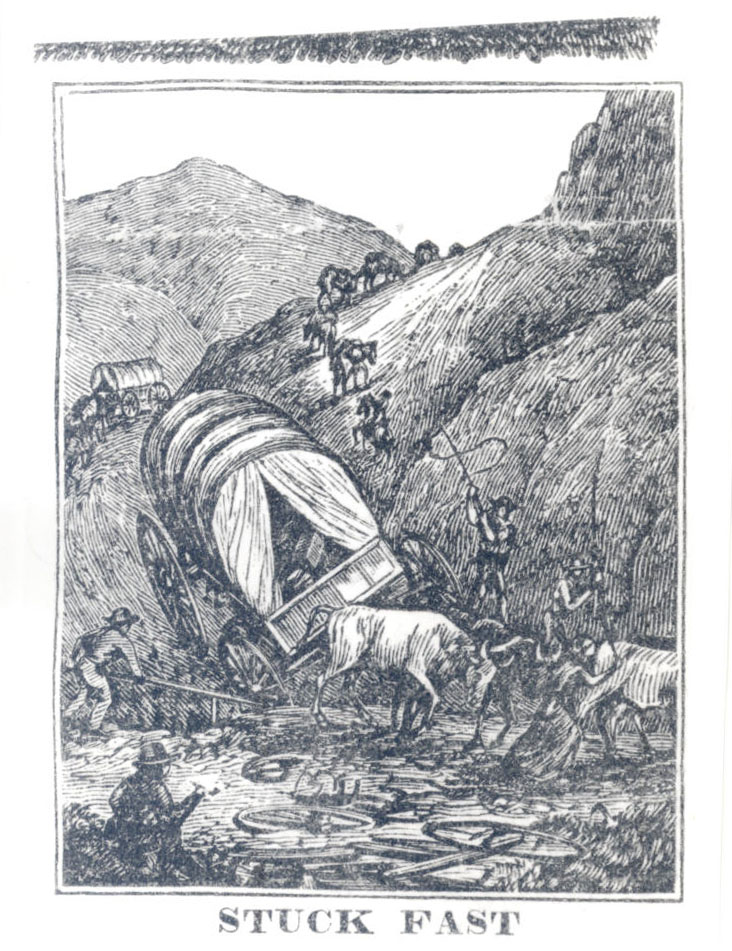

Stuck Fast..

Illustration of one of the many trail hazards: mud. Artist was George H. Baker, and his drawings appeared in Crossing the Plains, by J.M. Hutchings. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi39601

-

![]()

A departing wagon train during a re-enactment, c. 1890. Unknown location.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, Orhi5224

-

![Remnant of a wagon brought across the plains to Oregon by the donor's father, Daniel Waldo, in 1843. Made in Montana. Donated by John B. Waldo in 1900.]()

Wagon wheel hub, 1843..

Remnant of a wagon brought across the plains to Oregon by the donor's father, Daniel Waldo, in 1843. Made in Montana. Donated by John B. Waldo in 1900. Oregon Historical Society Museum Collection, 40.

Related Entries

-

![Applegate House]()

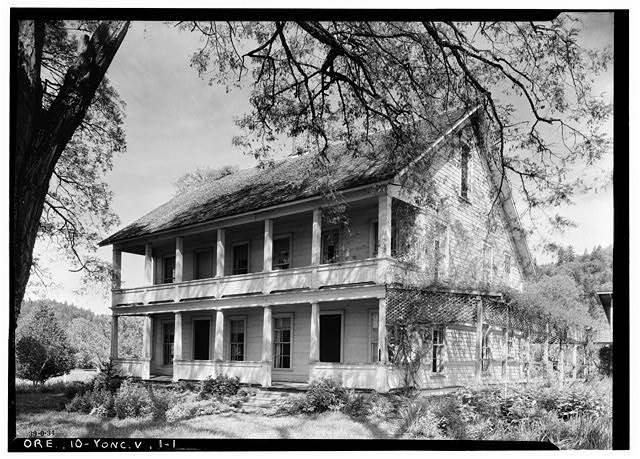

Applegate House

The Charles and Melinda Applegate House in Yoncalla is the oldest known…

-

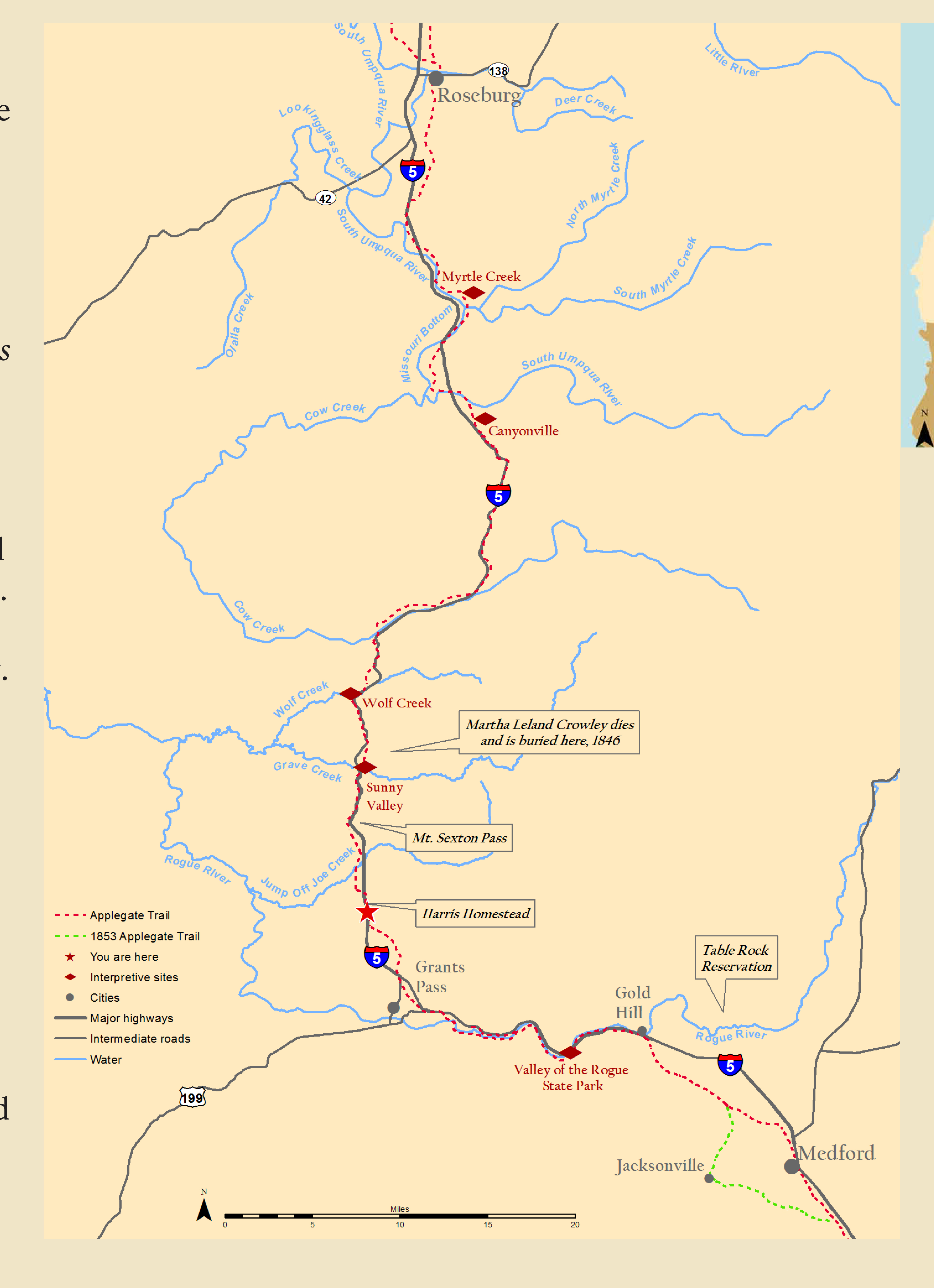

![Applegate Trail]()

Applegate Trail

The Applegate Trail, first laid out and used in 1846, was a southern al…

-

![Barlow Road]()

Barlow Road

The Barlow Road is a historic wagon road that created a new route on th…

-

![Hudson's Bay Company]()

Hudson's Bay Company

Although a late arrival to the Oregon Country fur trade, for nearly two…

-

Jesse Applegate (1811-1888)

Jesse Applegate, an influential early Oregon settler, is most remembere…

-

![John Minto (1822-1915)]()

John Minto (1822-1915)

John Minto described his sudden decision in 1844 to strike out for Oreg…

-

![John Shively (1804-1893)]()

John Shively (1804-1893)

John M. Shively was an Oregon pioneer who was active in territorial aff…

-

![National Historic Oregon Trail Interpretive Center]()

National Historic Oregon Trail Interpretive Center

The National Historic Oregon Trail Interpretive Center is located five …

-

Oregon Trail quilts

Quilts made by and for women who traveled the Oregon Trail between 1840…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Applegate, Jesse. “A Day with the Cow Column in 1843.” Oregon Historical Quarterly (December 1900): 371-83.

Barlow, Mary S. “A History of the Barlow Road.” Oregon Historical Quarterly (March 1902): 71-81.

Bowen, William A. The Willamette Valley: Migration and Settlement on the Oregon Frontier. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1978.

Burcham, Mildred Baker. ”Scott’s and Applegate’s Old South Road.” Oregon Historical Quarterly (December 1940): 405-23.

Clark, Keith, and Lowell Tiller. Terrible Trail: The Meek Cutoff. Caldwell, ID: Caxton, 1966.

Dary, David. The Oregon Trail. New York: Knopf, 2005.

Faragher, John Mack. Men and Women on the Overland Trail. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979.

Franzwa, Gregory W. The Oregon Trail Revisited. Gerald, MO: Patrice Press.

Haines, Aubrey L. Historic Sites along the Oregon Trail. Gerald, MO: Patrice Press, 1981.

Johnson, David Alan. Founding the Far West. Berkeley: University of Calififornia Press, 1992.

Kaiser, Leo, and Priscilla Knuth, eds. “From Ithaca to Clatsop: Miss Ketcham’s Journal of Travel, Pt. 2.” Oregon Historical Quarterly (December 1961): 397.

Kroll, Helen. “Books that Enlightened the Emigrants.” Oregon Historical Quarterly (June 1944): 102-123.

Mattes, Merrill J. The Great Platte River Road. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1969.

McClelland, John M., Jr. Cowlitz Corridor: Historical River Highway of the Pacific Northwest. Longview Publishing, 1953.

Miller, James D. “Early Oregon Scenes: A Pioneer Narrative (In Three Parts, I.): Overland Trail, 1848.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 31:1 (March 1930): 57.

Minto, John. “Reminiscences of Experiences on the Oregon Trail in 1844, Pt. II.” Oregon Historical Quarterly (September 1901): 212, 219.

Moore, Shirley Ann Wilson. “Sweet Freedom’s Plains: African Americans on the Overland Trails, 1841-1869.” Salt Lake City, UT: National Park Service, 2012.

Oregon Trail Emigrant Resources. Oregon State Library, Salem.

Parkman, Francis. The Oregon Trail: Sketches of Prairie and Mountain Life. New York: Knickerbocker Magazine, 1849.

Ragen, Brooks Geer. The Meek Cutoff. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013.

Reid, John Phillip. Policing the Elephant: Crime, Punishment, and Social Behavior on the Overland Trail. San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1997.

Richards, Kent. Young Man in a Hurry: Isaac Stevens. Provo, UT: BYU Press, 1979.

Ronda, James P. Astoria and Empire. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990.

Taylor, Quintard. “Freedmen and Slaves in Oregon Territory, 1840-1860.” In Peoples of Color in the American West, edited by Sucheng Chan, Douglas Henry Daniels, Mario T. Garcia, and Terry P. Wilson, 77-79. Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath, 1994.

Unruh, John D. The Plains Across. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1979.

Utley, Robert. A Life Wild and Perilous. New York: Henry Holt, 1997.

Vaughan, Chelsea. “’The Road that Won and Empire’: Commemoration, Commercialization and the Promise of Auto Tourism at the ‘Top o’ Blue Mountains.’” Oregon Historical Quarterly (Spring 2014): 6-37.