The Columbia River Gorge is a striking natural landscape of mountains, bluffs, and cliffs that border the Columbia River as it passes through the Cascade Range. The Gorge has been a barrier and then an artery for the movement of people and goods, a zone of changing economic activity, and, most recently, a defined political entity requiring cooperation among the states of Oregon and Washington, the federal government, and four Native American tribes.

Geology and Geography

The Columbia River shaped the Gorge as a physical place by carving through successive uplifts and volcanic outflows beginning about three million years ago and reaching something like its basic form about a million years ago. Raging floods of glacial meltwater known as the Missoula Floods further shaped the landscape, repeatedly crashing through the Gorge between 19,000 and 15,000 years ago. They stripped away loose talus and soil to shape its present landforms, creating landslide hazards from undercut slopes on the Washington side and turning mountain streams into hanging waterfalls on the Oregon side.

The Columbia River Gorge lies within six counties: Multnomah, Hood River, and Wasco in Oregon; and Clark, Skamania, and Klickitat in Washington. The western end of the Gorge is distinctly identifiable. To the southwest, the Sandy River marks a transition from high riverside bluffs to a much wider floodplain, rolling farmland, and the City of Troutdale. Across the Columbia, in Washington, high hills bend back from the river for the cities of Washougal and Camas.

The Gorge makes a uniform impression east to Hood River, Oregon, and White Salmon and Bingen, Washington. From those points eastward, however, the visible landforms change, the result of the Missoula Floods stripping away soil to expose the underlying layers of basalt. Vegetation transitions from thick Douglas-fir forest to a sparser rain shadow regime of oak, cedar, and ponderosa pine. Because of that dramatic change in the landscape and climate, some accounts use Hood River as the eastern end of the Gorge. Others extend it another thirty-six miles to include the historic navigation barriers of the narrow and hazardous channel that French visitors called Les Grandes Dalles de la Columbia and Celilo Falls, both now submerged by twentieth-century dams, with the mouth of the Deschutes River as a convenient end point. The Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area extends just east of the mouth of the Deschutes and Miller Island.

Trade and Transportation

The Columbia River Gorge served the first people of what is now Oregon as an important trade route. The vicinity of what is now The Dalles was both a natural break in travel routes and a border zone between the peoples of the lower Columbia and the inland peoples of the Columbia Basin. Thousands of people came together seasonally among the racks of drying salmon from the Celilo Falls fishery. They exchanged shells, fish oil, hides, and foodstuffs. When John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company arrived in 1811, its fur traders found that they had to deal with people who were already the custodians of Columbia River trade.

The Gorge was an important transportation route for Indigenous people and then fur traders in light canoes, but its falls and rapids presented a severe challenge for early settler colonists. English-speaking newcomers preferred to bypass the rainy, precipitous heart of the Gorge as an area for settlement in the mid-1800s, preferring the fertile Willamette Valley and the gold fields of the upper Columbia Basin. Not until the 1860s did Portland entrepreneurs put together a system of steamboat routes on the upper and lower river, connected by portage railroads at Cascade Locks and The Dalles and later unified by sets of locks that replaced the portage railroads. The Oregon Steam Navigation Company was Portland’s first “millionaire-making machine,” in the words of historian Dorothy Johansen. By 1883, long-distance railroads that tied western Oregon to the eastern states had opened along the Oregon side of the Columbia River to connect to the Northern Pacific system (the Oregon line is now part of the Union Pacific) and on the Washington side in 1908 (Spokane, Portland, and Seattle Railway, now Burlington Northern–Santa Fe).

The waters and lands of the Gorge were incorporated into the regional economy beginning in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Salmon was harvested by the thousands for riverside canneries. Logging railroads pushed toward Mount Hood and Mount Adams, flumes carried logs to the river, and residents of mill towns such as Bridal Veil turned them into lumber. The Hood River Valley blossomed with fruit trees early in the twentieth century, with Anglo American and Japanese American orchardists and loggers clearing the forests. The volume of timber cut in Gorge counties peaked in the late 1960s and remained high until an abrupt decline in the late 1980s, caused by economic recession and environmental regulations.

Dam-building in the mid-twentieth century altered both the Gorge and the greater Pacific Northwest. Bonneville Dam (1937) and The Dalles Dam (1957) inundated the rapids that gave the name to Cascade Locks and drowned Celilo Falls. The impounded pool behind Bonneville Dam is a sharp contrast with the dangerous river that travelers encountered in earlier times. The two dams established key links in a barge navigation corridor from Portland-Vancouver to the Washington Tri-Cities and Lewiston, Idaho. Nineteenth-century transportation tycoons would be impressed to see the lines of trucks weaving in and out of traffic on Interstate-84, long strings of railcars squealing by on both sides of the river, and barge tows pounding with and against the current—all at the same time.

Popular Culture and Tourism

The term “Columbia River Gorge” appears sparingly in nineteenth-century maps and documents. Early explorers and travelers described individual features of the river and landscape but not a unified region. In the 1880s, however, railroads and steamboat lines began to promote tourism and offer excursions on which the landscape of “uninterrupted magnificent display,” as the Union Pacific Railway described it, would nurture “aesthetic enjoyment and hygienic exhilaration.” Francis Fuller Victor, in her Atlantis Arisen, or Talks of a Tourist around Oregon and Washington in 1891, identified the Gorge as a place where “wonder, curiosity, and admiration combine.”

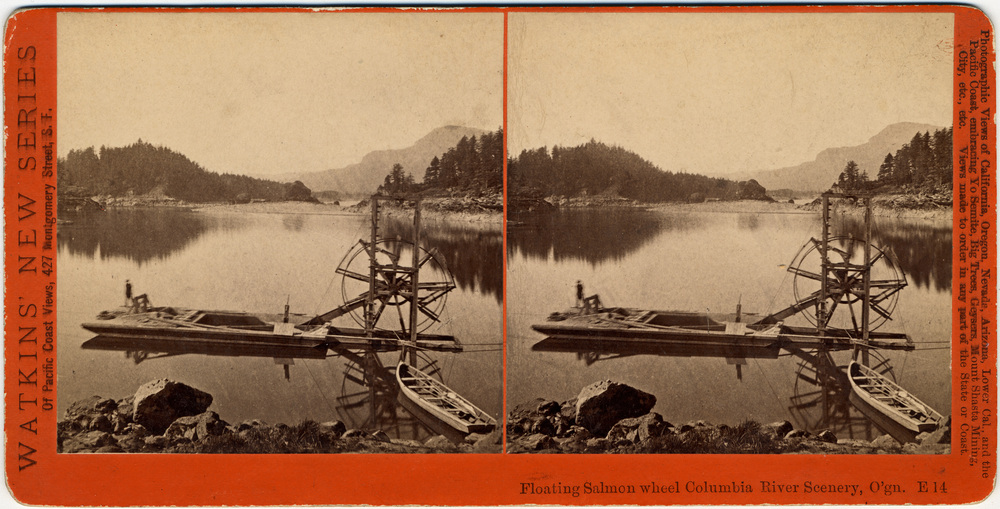

Photography played an important role in shaping perceptions of the Gorge. Carleton Watkins arrived from California in 1867, traveling by steamboat to photograph both the landscape and the human imprint with his cumbersome equipment. He returned in the early 1880s to make a new series of images. At the start of the twentieth century, Lily White and her friend Sarah Ladd cruised the river on White's eighty-foot houseboat, taking photographs of its towering cliffs, some of which appeared in Ladd's 1904 book Columbia River Scenery.

Attention to the Gorge as a distinct region increased substantially with construction of the Columbia River Highway in the 1910s and grew to a first peak around 1940. A key publication among a freshet of guidebooks and tourist pamphlets was Ira A. Williams’s The Columbia River Gorge: Its Geologic History as Interpreted from the Columbia River Highway, from the Oregon Bureau of Mines and Geology. Published in 1916 and reissued in 1923 because of “unusually big demand,” the book was both a summary of Gorge geology and a tourism-boosting guide to the highway from Portland to Hood River.

The Columbia River Gorge has made occasional appearances in popular culture and literature. In The Bend of the River, a 1952 film, James Stewart rides a steamboat upstream from Portland before encountering adventures on the slopes of Mount Hood. The Dalles in the boom times of the early twentieth century appears anonymously in H. L. Davis’s Honey in the Horn (1935). Craig Lesley’s River Song (1989) follows Danny Kachiah (Nez Perce) and his son to several stops along the Columbia River, including a stint as a migratory worker in the Hood River orchards and a fight to maintain Native fishing rights in the Gorge.

Conservation and Management

Conservation of the Gorge became a hot topic with construction of Bonneville Dam in the 1930s. The question was whether the power would support manufacturing close to the dam itself or be sent to Portland and other established industrial centers. A key document was Columbia River Gorge Conservation and Development, developed by a committee chaired by Portland architect John Yeon and published in 1937 by the Pacific Northwest Regional Planning Commission. The report vigorously argued for protecting the Gorge from heavy industry. Yeon's position found self-interested support from Portland's economic and civic leadership, and it prevailed in World War II, when electricity-hungry aluminum plants were built in Troutdale and Vancouver, Washington.

The Gorge emerged as an object of governmental concern in the 1950s, and members of the public began to worry about preserving its scenic and recreational values. Members of the Portland Women's Forum, particularly Gertrude Jensen, spearheaded the work. They were instrumental in the creation of publicly appointed advisory and advocacy groups, the Oregon Columbia River Gorge Commission (1953) and its Washington counterpart (1959). The Columbia Gorge Coalition (1979), organized by activist Chuck Williams (Cascade Chinook), and the Friends of the Columbia Gorge (1980), led by the indefatigable Nancy Russell, opened agitation for differing versions of federal protection. Those organizations made formal land use regulation and management a hot political issue, culminating in the creation of the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area in 1986.

The Scenic Area itself extends east-west for eighty-five miles along the Columbia River and north-south between the crests of the mountains and bluffs that line the river for a width that varies from one to four miles. Its 458 square miles are parceled among a Special Management Area where land uses are more restrictive and managed by the U.S. Forest Service; a General Management Area managed by a bi-state Columbia River Gorge Commission and Gorge counties; and thirteen Urban Areas that directly manage land uses according to their own plans and rules.

Into the Twenty-First Century

The official boundaries of the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area partition off portions of larger social and economic systems, dividing Hood River, Wasco, Klickitat, and Skamania Counties and taking tiny slices from Clark and Multnomah Counties. The Gorge economy at the beginning of the 2020s was a mixture of older resource industries: forest products operations at Cascade Locks, Stevenson, and Bingen; recreation and tourism keyed by windsurfing and kiteboarding, concentrated in Hood River and White Salmon; and new high-technology companies such as Insitu in Bingen and Google in The Dalles. Logging, farming, and especially horticulture are continuing mainstays of the four core counties, but they are largely carried on outside the relatively narrow physical boundaries of the Gorge.

The population of the Gorge has grown steadily since the nineteenth century. In round numbers, official state population estimates counted 35,000 people in Skamania and Klickitat Counties in 2020 and 53,000 in Wasco and Hood River Counties. The thirteen urban areas within the Scenic Area include eight incorporated cities with precise population data available and five unincorporated areas whose boundaries for the Scenic Area may differ from the census enumeration areas. The incorporated cities in Washington (with 2020 estimates) are White Salmon (2,710), Stevenson (1,665), North Bonneville (1,035), and Bingen (750). In Oregon, they are The Dalles (14,845), Hood River (8,565), Cascade Locks (1,420), and Mosier (490). The unincorporated urban areas within the Scenic Area, all in Washington, are Carson, Home Valley, Lyle, Dallesport, and Wishram. In total, approximately three quarters of the residents of the four core counties live in the Scenic Area.

The Gorge is both a passageway and a place. Find the right location at the right time and you might see a whole inventory of transportation—a barge tow pounding upriver, long freight trains on both banks, trucks on Washington Route 14 and Interstate 84, and motorists and bicycles on the historic highway. At the same time, the Gorge is a magnificent landscape that attracts millions of visitors. Few traces of early industrial fishing and logging remain, supplanted by brew pubs and trailhead parking lots. But as the tourists come and go, it remains home to more than 100,000 people.

-

![]()

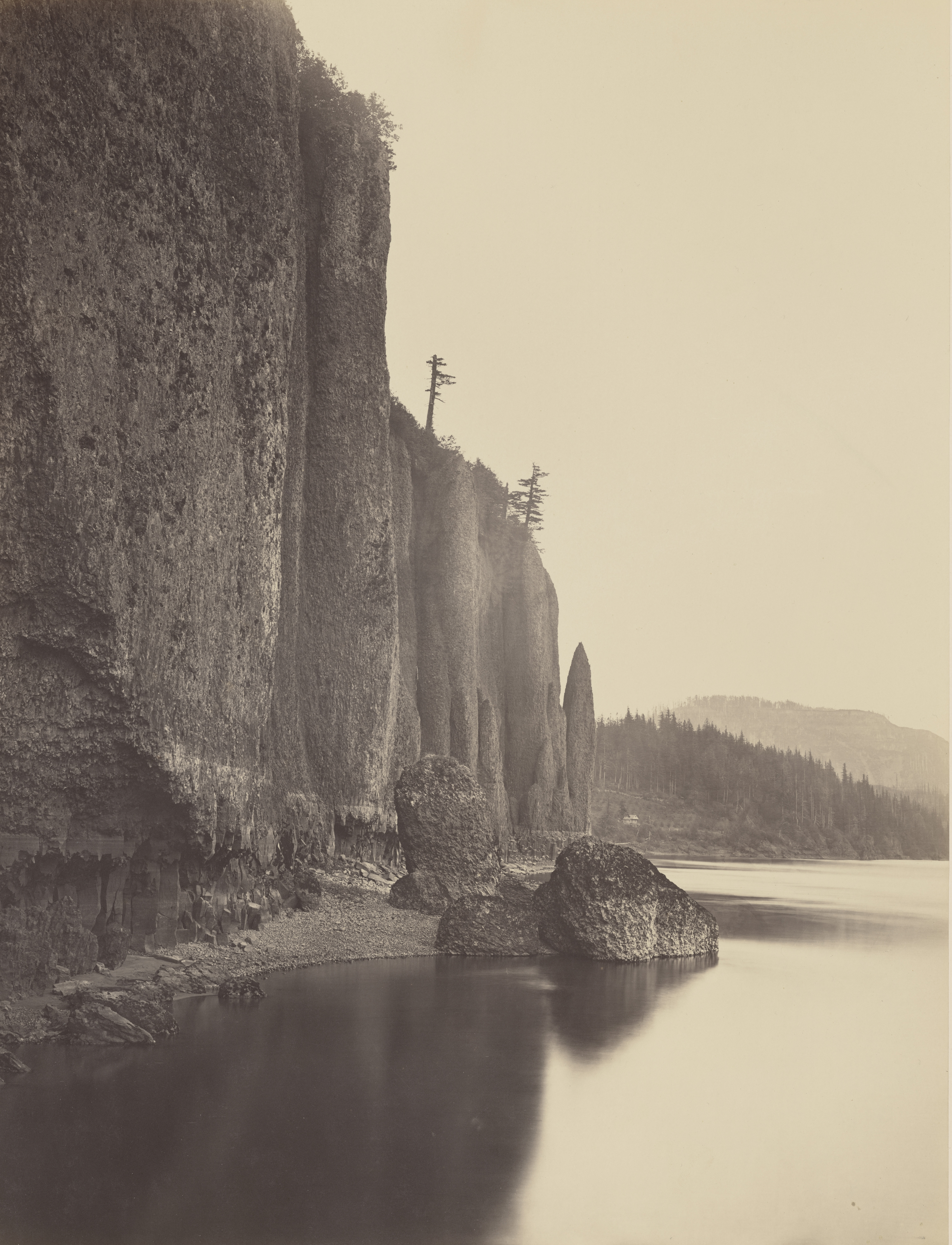

"Cape Horn. Columbia River," by Carleton Watkins, 1867.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Watkins, OrgLot93_Mammoth_419 -

![]()

Columbia River Gorge.

Courtesy National Park Service -

![]()

"The Passage of The Dalles. Columbia River," Carleton Watkins, 1867.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Watkins, OrgLot93_Mammoth_454_01 -

![]()

"Distant View of Castle Rock, Columbia River," Carleton Watkins, 1867.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Watkins, OrgLot93_Mammoth_426_01 -

![]()

"Islands in the Columbia. Upper Cascades," by Carleton Watkins, 1867.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Watkins, OrgLot93_Mammoth_441 -

![]()

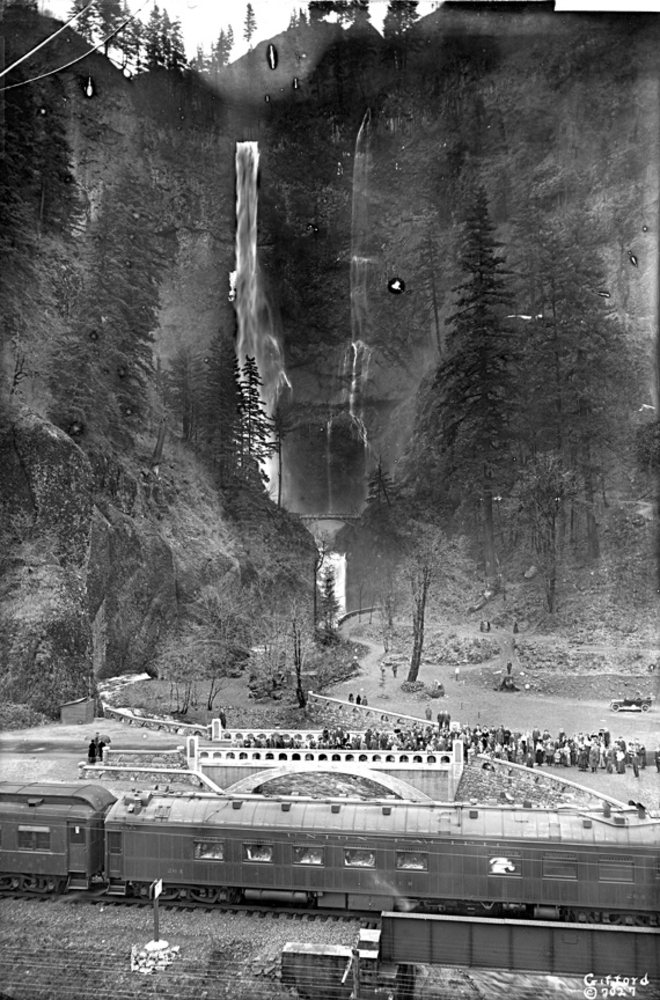

Sternwheeler Bailey Gatzert, Multnomah Falls, 1890.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Kiser Studios, OrgLot78_B6F6_002 -

![]()

View of Columbia River from White Salmon, Washington, Lily White and Sarah Ladd, c.1902.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, White and Ladd, Album201_010 -

![]()

Columbia River at Sunset, c.1904.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Fred Kiser (colorized by Winter Photo co, bb000186 -

![]()

Rooster Rock, Columbia River Gorge, c.1903-1925.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Kiser Studios, OrgLot78_B2F6_006 -

![]()

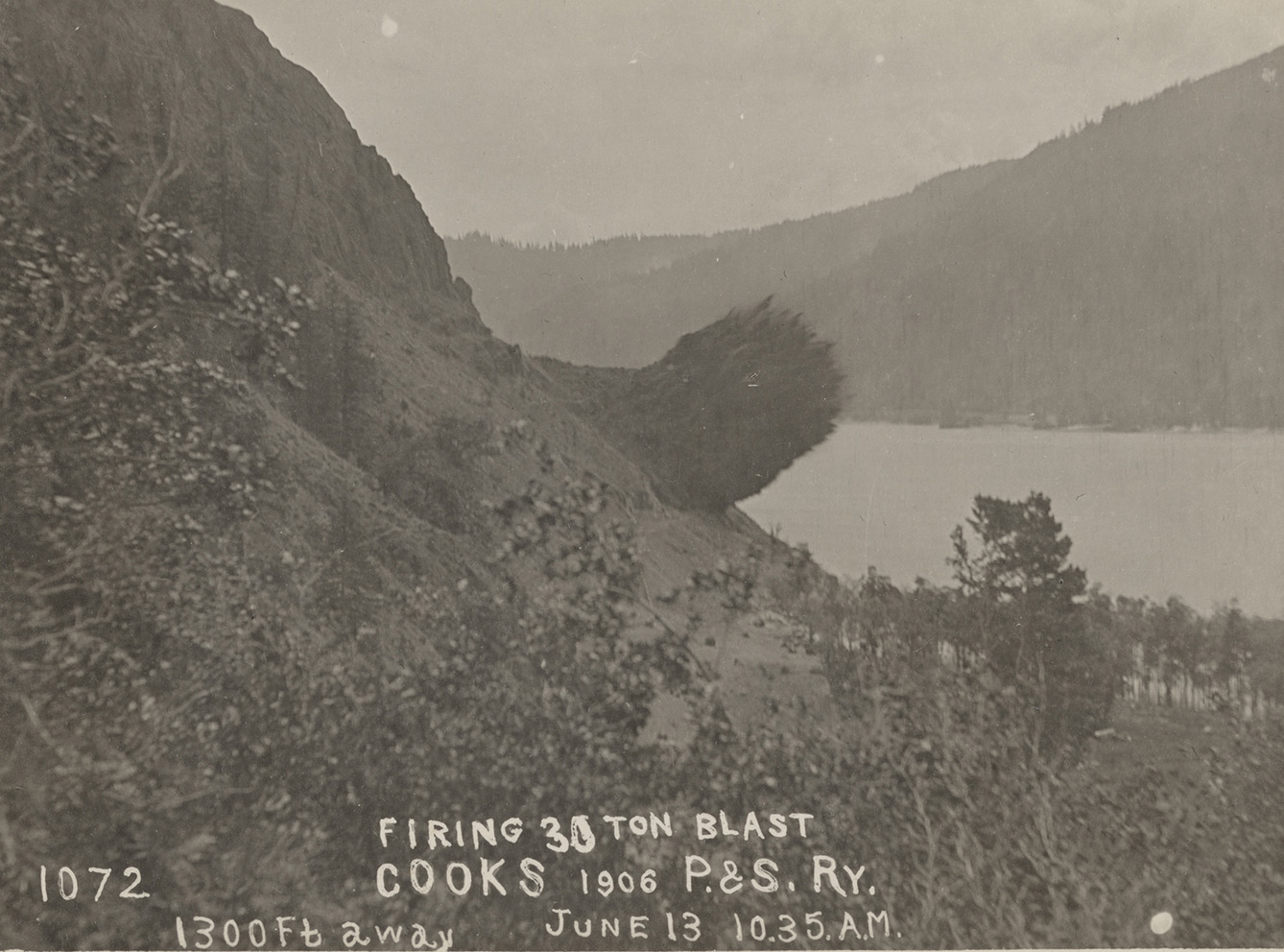

Blasting the cliffs along the Columbia River Gorge to build a railroad, Washington side, 1906.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Spokane, Portland, and Seattle Railway, OrgLot78_B4F9_002 -

![]()

Columbia River Gorge, by Lily White, c.1910.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Lily White, OrgLot1415_LW2_029 -

![]()

Aerial photograph of Hood River, 1932.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Roy Norr, 371N5716 -

![]()

-

![]()

Logging in the Columbia River Gorge, 1954.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Al Monner, Org. Lot 1284_1964_6 -

![]()

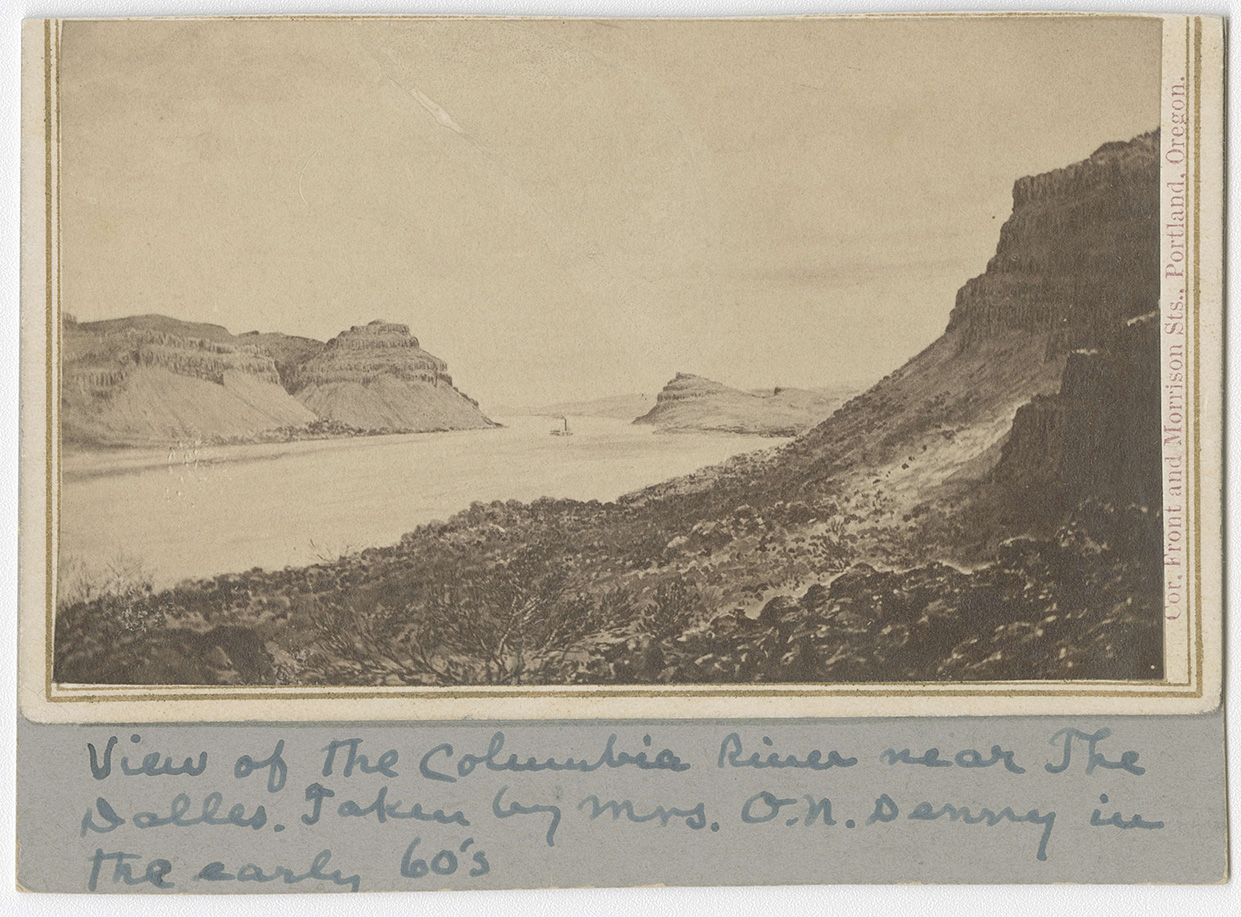

Columbia River Gorge, near The Dalles, c. 1860.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Gertrude Denny, OrgLot 500_A_342 -

![Vista House sits on the right.]()

Columbia River Gorge looking east from Women's Forum State Park, Oregon..

Vista House sits on the right. Courtesy U.S. Geological Survey -

![]()

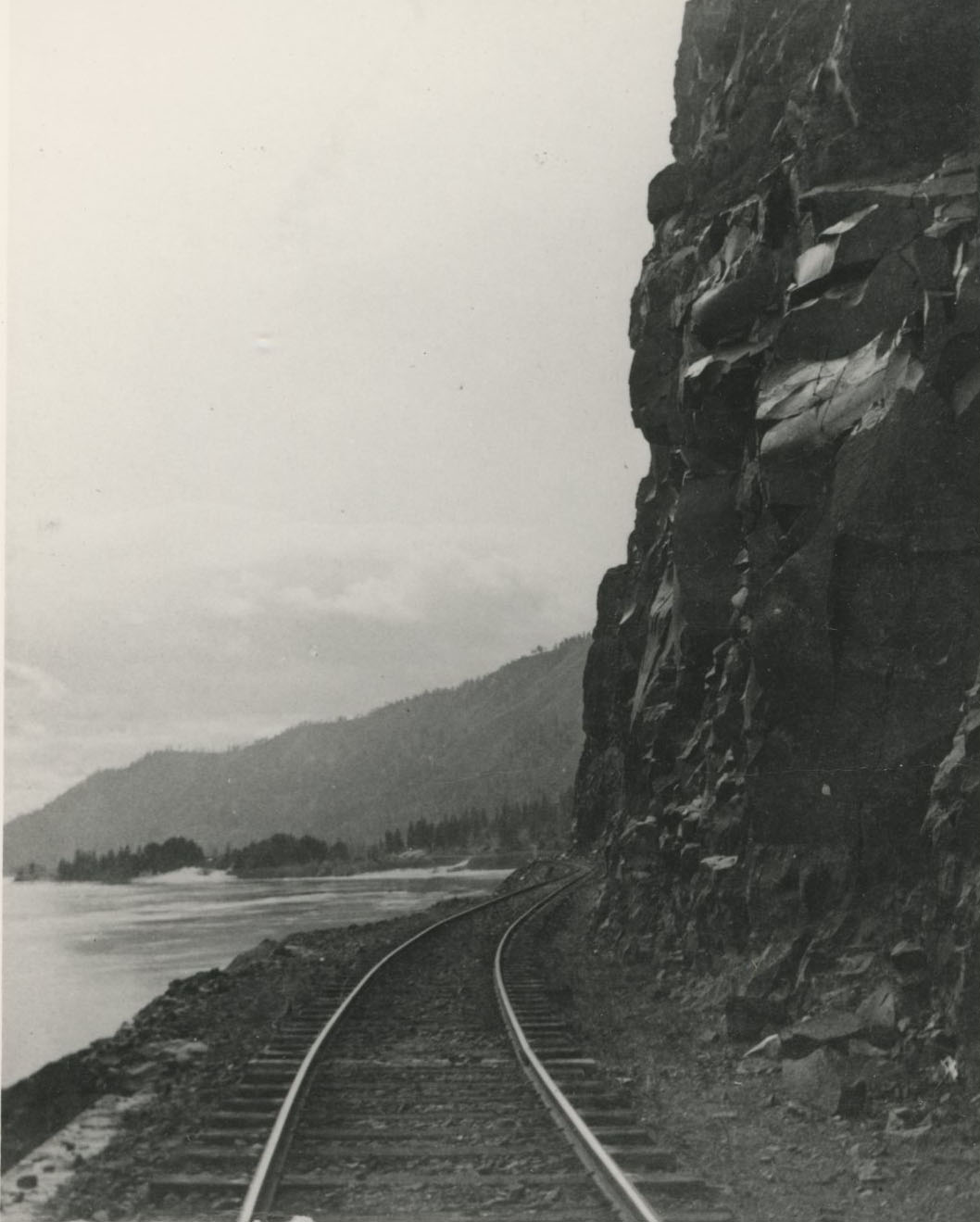

Tracks of the OR&N Line exit Tunnel # along the Columbia River Gorge.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 016291

-

![]()

Columbia Gorge Hotel.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 018653

-

![]()

Multnomah Falls.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb003158

Related Entries

-

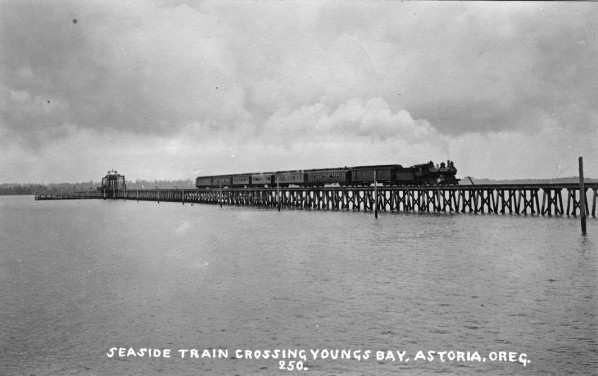

![Astoria and Columbia River Railroad]()

Astoria and Columbia River Railroad

Ever since Astoria was founded at the mouth of the Columbia River in 18…

-

![Carleton Emmons Watkins (1829-1916)]()

Carleton Emmons Watkins (1829-1916)

Carleton Emmons Watkins was a prominent San Francisco-based photographe…

-

Celilo Falls

Celilo Falls (also known as Horseshoe Falls) was located on the mid-Col…

-

![Columbia River]()

Columbia River

The River For more than ten millennia, the Columbia River has been the…

-

![Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area]()

Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area

Established by Congress in 1986, the Columbia River Gorge National Scen…

-

Columbia River Highway

The Columbia River Highway, now known as the Historic Columbia River Hi…

-

![Hood River (city)]()

Hood River (city)

Situated in the Columbia River Gorge about sixty miles east of Portland…

-

![Lily Edith White (1866-1944)]()

Lily Edith White (1866-1944)

Photographer Lily White once professed: "Alone—controlling the power, d…

-

![Oregon Steam Navigation Company]()

Oregon Steam Navigation Company

Among early business enterprises in Oregon, the Oregon Steam Navigation…

-

![The Dalles]()

The Dalles

The Dalles is one of the oldest permanently occupied places in Oregon, …

-

![Western Oregon Klikatats (Klickitats)]()

Western Oregon Klikatats (Klickitats)

Between the 1810s and 1850s, a sizable segment of the Klikatat Tribe of…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Abbott, Carl, Sy Adler, and Margery Post Abbott. Planning a New West: The Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 1997.

Allen, John Eliot, Marjorie Burns, and Scott Burns. Cataclysms on the Columbia: The Great Missoula Floods. Portland: Ooligan Press, 2009.

Barber, Katrine. Death of Celilo Falls. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005.

Durbin, Kathie. The Columbia River Gorge: Bridging a Great Divide. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2013.

Hirt, Paul. A Conspiracy of Optimism: Management of the National Forests since World War II. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996.

Tamura, Linda. The Hood River Issei: An Oral History of Japanese Settlers in Oregon’s Hood River Valley. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993.