Between the 1810s and 1850s, a sizable segment of the Klikatat Tribe of present-day south-central Washington occupied parts of the Willamette, Umpqua, and Rogue Valleys. Their expansion into Oregon Territory is a strong regional example of how, all along the western frontier, exposure to EuroAmericans changed the cultures and territories of Native people. Even though Klikatats were not native to Oregon, their influence was so strong during their brief presence there that their name became identified with the Territory. Their 1855 repatriation to Washington by Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer is one of the first examples in Oregon of forced governmental removal of an entire ethnic group from lands they considered their homes.

Klikatat (also Klickitat; the Klikatat spelling is from the 1855 Yakama Treaty) are a Northwest Sahaptin-speaking people whose traditional territory was north of the Columbia River in present-day Klickitat, Skamania, and east-central Clark Counties in Washington. Their self-designation is xwa’lwaypam, or Stellar’s Jay People. Upper Chinook speakers called them Klikatat, after ladaxat, a village at the mouth of the Klickitat River (a tributary of the Columbia east of the Cascade Range), and that name was extended to other Northwest Sahaptin bands on the western flank of the Cascades in Washington State.

The Klikatat are known for their elaborate, looped top, coiled imbricated basketry, whose sophisticated designs make the baskets a hallmark of the region. They dug camas roots, collected berries in prairie openings, and fished for salmon along with Upper Chinook tribes. They also were noted elk hunters who traded hides to other Native groups for making arrowproof clamons (elkskin armor), and they were incredibly good horse soldiers.

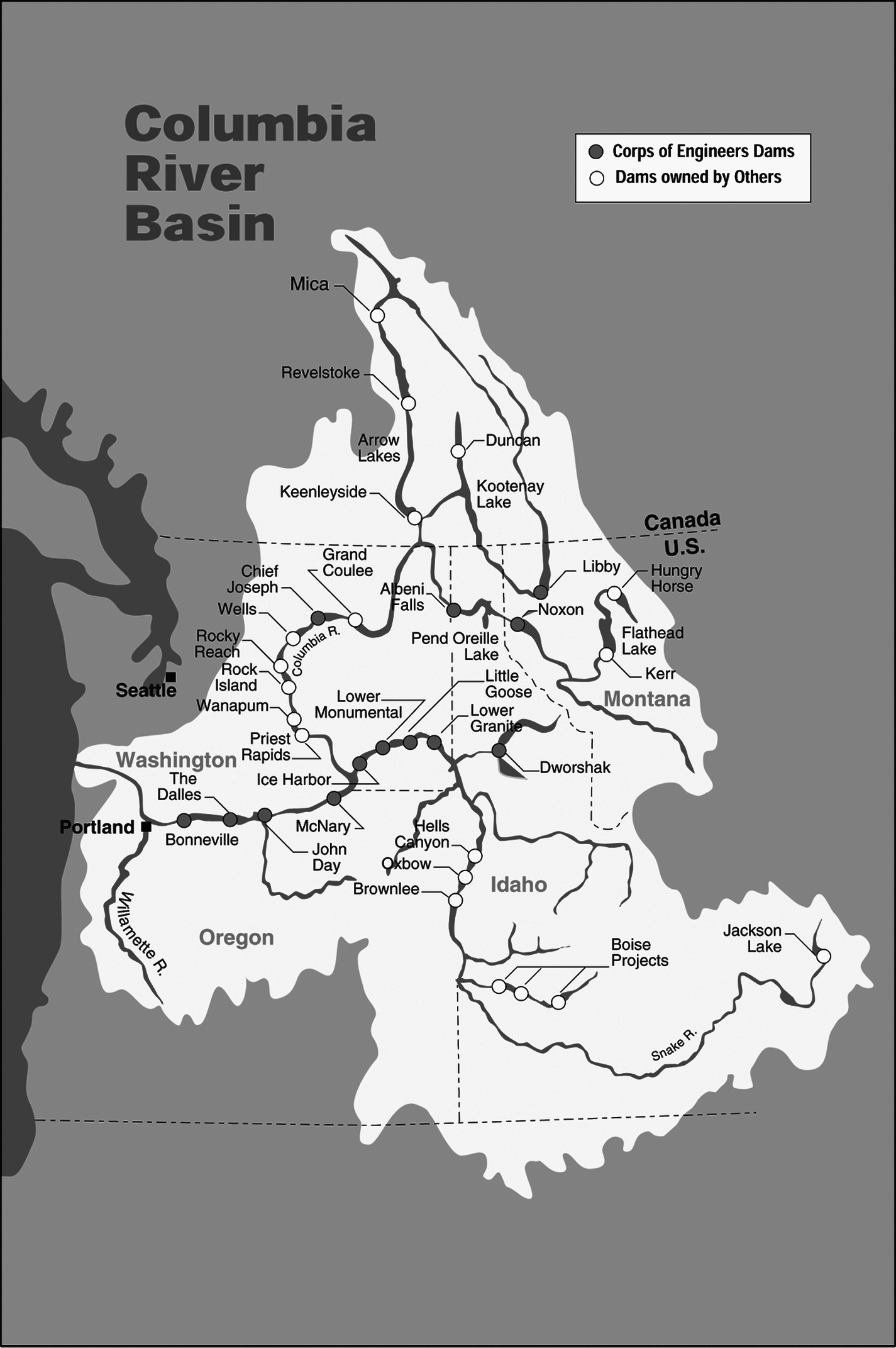

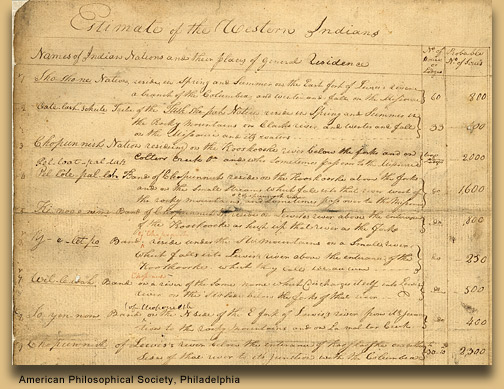

When Meriwether Lewis and William Clark passed through the Columbia River Gorge in 1805-1806, Klikatats (called Wah-how-pum by the explorers) were in their homeland north of the Columbia along the eastern face of the Cascade Mountains in present-day Washington State. In the early eighteenth century, spurred by the adoption of the horse and a cultural shift to a migratory horse culture, they began making forays into the rich resource areas west of the Cascades in Oregon and Washington.

In February 1814, fur trader Alexander Henry provided the first written documentation of Klikatats west of the Cascades. His journal recorded an encounter with a mounted party of “Walla Walla, Walla Shatasla, and Halth-oy-pum” (Walla Walla, Satus [Yakama], and Klikatat) hunting in the Willamette Valley. They entered the area on mountain trails in the southern Washington and northern Oregon Cascades on former foot trails recently transformed to unbroken horse transportation routes dotted with clearings for forage.

For the next twenty years, Klikatats were noted only sporadically in the documentary record west of the Cascades, as populous communities of Chinookans, Kalapuyans, and other Native peoples created a barrier to their settlement. But in the summer of 1830, and in succeeding summers over the next few years, annual outbreaks of “fever and ague” (epidemiologically, virgin-soil malaria) killed thousands of people in the Cowlitz, Portland, Columbia, and Willamette Basins. The epidemic left many areas unoccupied along the Columbia River and in the Willamette Valley, as smaller villages disappeared. With fewer people, the tribes and bands could no longer defend their homelands from encroachment and resettlement, and Klikatat, Molala, Taytnapam (Upper Cowlitz), and then white Americans began moving into their lands.

In the late 1830s, William Tolmie, the chief trader for the Hudson’s Bay Company, invited a band of Klikatats to settle near Fort Vancouver, where they began a productive relationship that provided material goods and guns for themselves and agricultural labor and hunters for the company. The 345 Klikatats who were counted for the census in the vicinity of the fort in 1838 were wealthy (with 67 horses and 58 guns) and prolific (45 percent were children). The acquisition of guns had a significant impact on game populations. According to ethnologist George Gibbs (using information from Nez Perce leader Hal-hal-tlos-tsot, also known as Lawyer), overhunting by Klikatats led to the disappearance of mountain goats and sheep from the southern Washington Cascades and to declines in elk and deer populations.

By 1839, under Quatley and other leaders, Klikatat bands were visiting and settling in the Willamette Valley, where the Kalapuya population had been diminished by disease. They were attracted to the rich hunting grounds, pastures, and camas fields. Klikatats forded their horses over the Columbia River between Wakanasese, a village on the north bank below Fort Vancouver, and Multnomah, a former village on Sauvie Island, and ascended the Tualatin Mountains on trails to the Tualatin and Willamette Valleys. These trails became known as Klickatat trails.

For the next dozen and more years, Klikatats lived on the Willamette Valley prairies, and some traveled to hunting grounds as far south as the Umpqua, Coos, and Rogue Valleys. The hunters met little resistance from the people who remained in the valleys, though there were some incidents with Mary’s River Kalapuya, Umpqua, and Siuslaw. Stories from western Oregon tribes suggest that the Klikatat were swift and efficient mounted infantry who were feared for their ferocity and who attacked Native villages.

Within this same period, a Klikatat band in the upper Willamette Valley reportedly “purchased” land from local Kalapuyans, which in the 1850s became the basis for their claim that they had conquered the Kalapuyans and owned the Willamette Valley. Klikatats crossed the Coast Range to the Pacific between the homelands of the Coquille, Coos Bay, and Siletz and traded with the tribes there. In the early 1850s, American settlers in Coos County and the Umpqua Valley complained that Klikatats were coming annually and slaughtering the elk herds for their hides.

Klikatats became known as middlemen in the Northwest fur trade, bringing horses, guns, clothing, and other goods from Fort Vancouver (and later, from American settlements) to western Oregon tribes and trading furs, hides, and slaves in return. During the 1855-1856 Rogue River Indian wars, an Indian agent’s correspondence suggested that Klikatats were supplying the Rogue River Confederacy with guns and ammunition, prompting a call for their expulsion from Oregon Territory. They also reportedly traded with the Coos Bay people.

Some Klikatat men allied with the volunteer territorial militia to serve as scouts and mercenaries in conflicts with Rogue River tribes. Their aim in those alliances appears to have been to curry favor among white settlers and to gain an opportunity to expand their range farther into southern Oregon. During 1853 peace treaty negotiations, Gen. Joseph Lane used Klikatats to intimidate Rogue River tribes, and Klikatats held Apserkahar (Chief Jo) hostage to thwart an attempt by the Rogue Indians to capture the general. They did not release Apserkahar until the treaty was signed.

One 1851 census reported 492 Klikatats in Oregon, while a second reported 587. In Clark County, in present-day southwest Washington State, an 1854 census of Native settlements revealed that most Chinookan villages had transitioned to Sahaptin occupation, by both Klikatats and the related Northwest Sahaptin Taytnapam (Upper Cowlitz) people. Klikatats also increasingly intermarried with Métis and Natives west of the Cascades, including Chinookans, Kalapuyans, Umpqua, and Rogue River people in Oregon.

From 1843 through 1855, American resettlers began colonizing western Oregon. Particularly after 1850, when Donation Act land claimants began parceling out and fencing the prairies, conflicts between mounted Klikatats and white resettlers became more and more frequent. Formerly unimpeded access to resource areas and hunting grounds was redefined as trespass, and fences created barriers to the free movement of mounted bands. Some Klikatat families attempted to settle and farm, but conflicts had become so frequent by the mid-1850s that co-occupation of the Willamette Valley became untenable.

Increasing complaints to Joel Palmer, the Oregon territorial superintendent of Indian Affairs, led him to propose in 1854 that Oregon Klikatats be removed to their ancestral homelands north of the Columbia. Since their traditional homeland was north of the Columbia, the Oregon Klikatats were not part of the 1855 Oregon treaty negotiations and were denied a land claim in Oregon. The removal of several hundred Klikatats was carried out in August 1855, first to a temporary reserve at present-day White Salmon, Washington, and later to Yakama. Displaced Oregon Klikatats formed a large segment of the Indians allied with Kamiakin in the 1856 Yakama Wars, who in March of that year made a coordinated attack on white resettlements along the Columbia River, notably on the lower Lewis River and at the Cascade Rapids. At Cascade Rapids, while the Klikatat leaders escaped and leaders like Kamiakin were pursued for many years after, eight Cascades (Watlala) leaders were blamed for taking part in the attack and seven were executed in late March 1856.

Today, most Oregon Klikatat descendants are enrolled members of the Yakama Nation, and many members of the Grand Ronde and Cowlitz tribes have Klikatat ancestry. Klikatats were caught up in the removal of Willamette Valley tribes to the Grand Ronde Reservation in 1856, and Indian Agency records suggest that some remained on the reservation. Individual Klikatat men settled in the Umpqua Valley, Dallas, Oregon City, St. Helens, and Blue Lake, and many of them married local Native women. Place-names such as Klickitat Mountain in the Siuslaw National Forest and several historic Klickatat trails recall the Klikatats’ time in Oregon.

-

![]()

Klickitat identified as Sally Waukiagus by photographer Lily White.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi87886

-

![]()

Klickitat identified as Chief Skookum Waiiahee by photographer Lily White, c.1902.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 70219

-

![]()

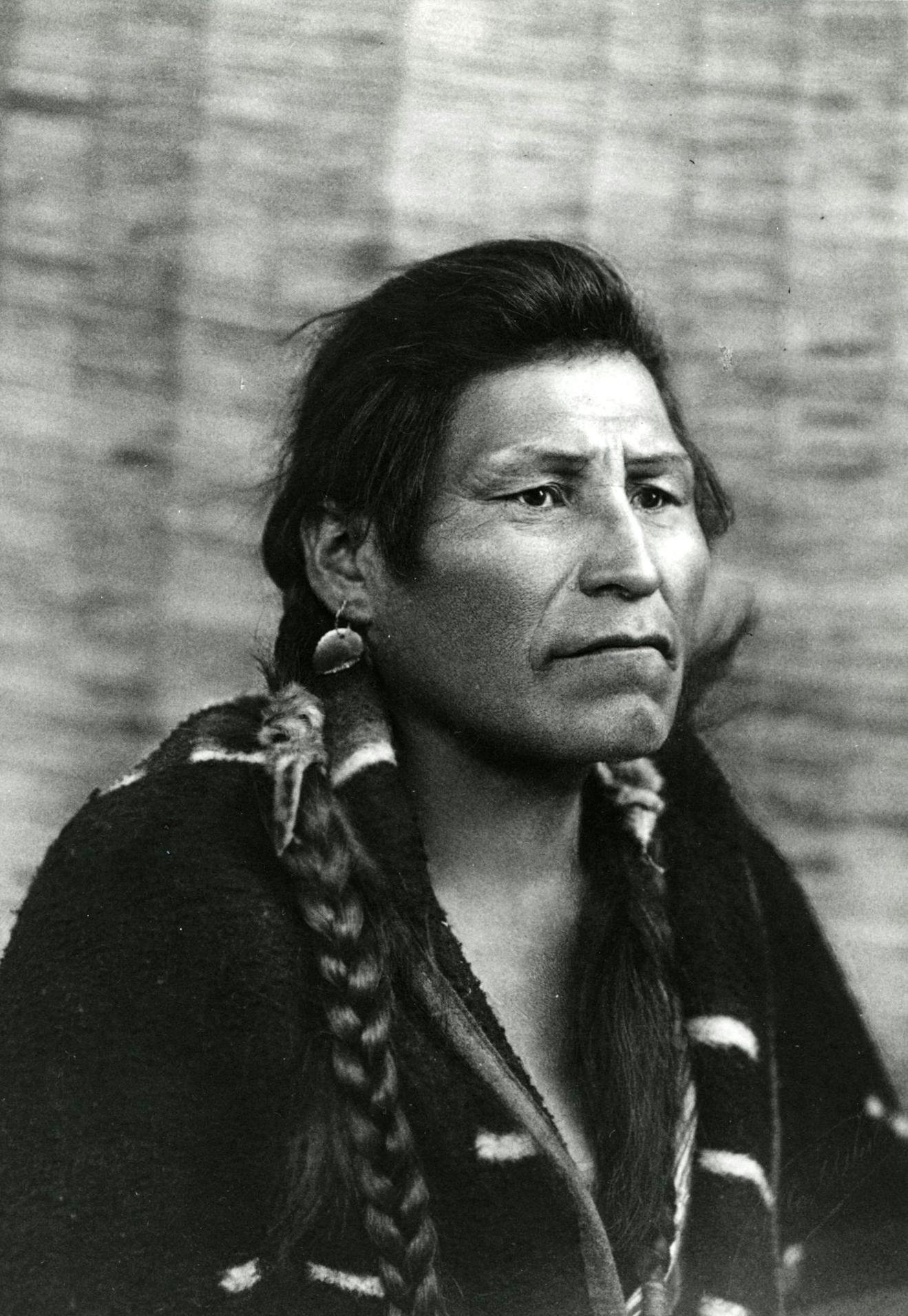

"A Klickitat Brave," by Benjamin Gifford, 1899.

Courtesy OSU Special Collections & Archives Research Center, Oregon State University. ""Klickitat brave"" Oregon Digital -

![]()

-

![]()

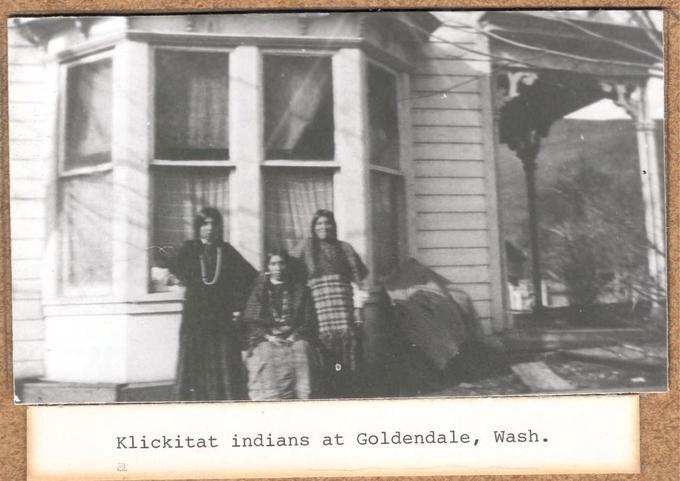

Klickitat Indians, Goldendale, Washington.

Courtesy Columbia Gorge Discovery Center Photo Archive, Oregon State University. "WCPA 205A-5" Oregon Digital -

![]()

The Klickitat River in Washington, by Lily White.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi88133

Related Entries

-

![Camas]()

Camas

Camas is a North American bulb-forming geophyte whose greatest diversit…

-

![Columbia River Treaty (1964)]()

Columbia River Treaty (1964)

The high-voltage power lines that march across central Oregon, linking …

-

![Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde]()

Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon is a confede…

-

![Fort Vancouver]()

Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver, a British fur trading post built in 1824 to optimize th…

-

![Kalapuyan peoples]()

Kalapuyan peoples

The name Kalapuya (kǎlə poo´ yu), also appearing in the modern geograph…

-

![Multnomah (Sauvie Island Indian Village)]()

Multnomah (Sauvie Island Indian Village)

"Multnomah" is a word familiar to Oregonians as the name of a county an…

-

![Portland Basin Chinookan Villages in the early 1800s]()

Portland Basin Chinookan Villages in the early 1800s

During the early nineteenth century, upwards of thirty Native American …

-

![Willamette Valley]()

Willamette Valley

The Willamette Valley, bounded on the west by the Coast Range and on th…

-

![Willamette Valley Treaties]()

Willamette Valley Treaties

From 1848 to 1855, the United States made several treaties with the tri…

Related Historical Records

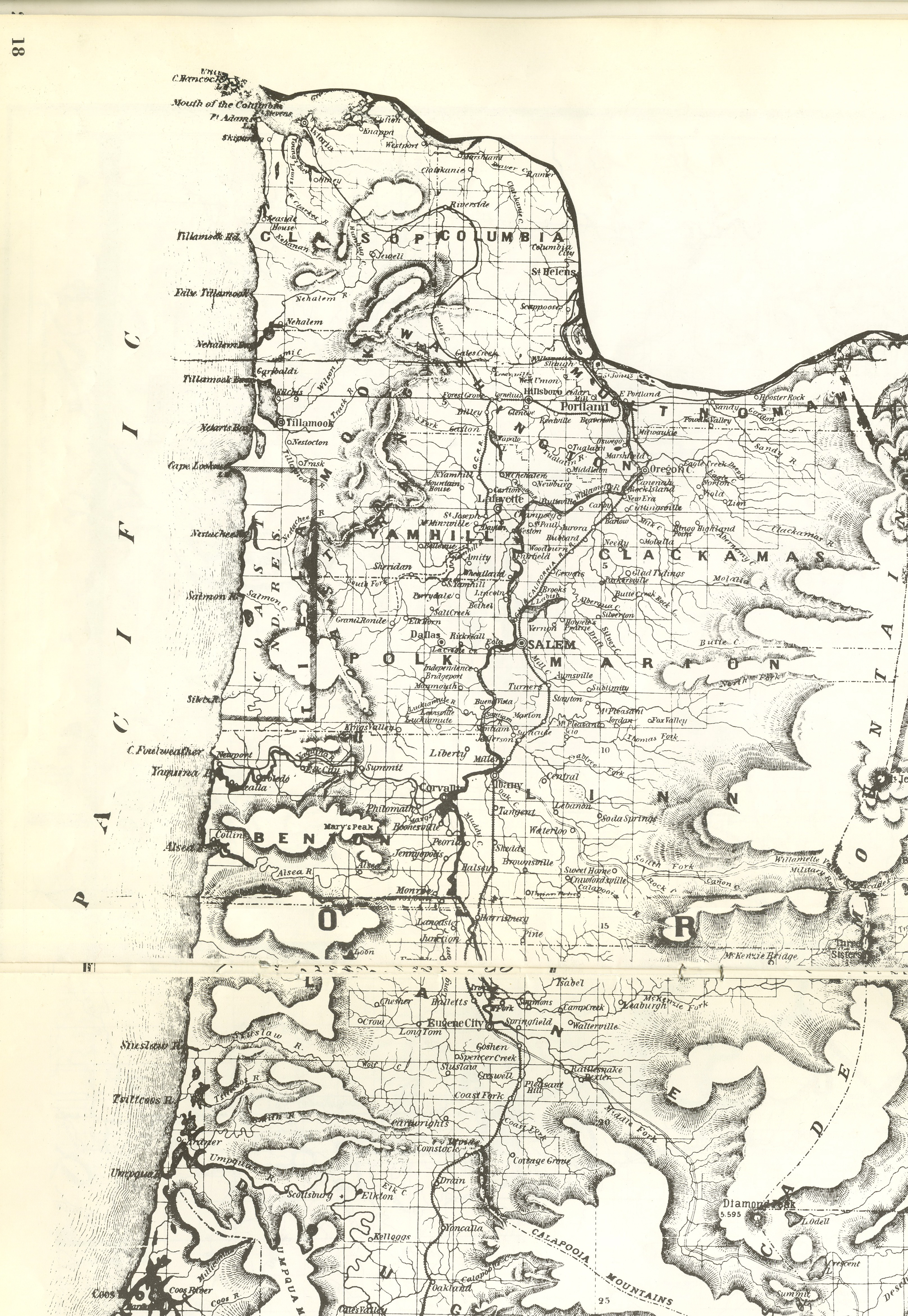

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Boyd, Robert. The Coming of the Spirit of Pestilence: introduced infectious diseases and population decline among Northwest Coast Indians, 1774-1874. Seattle: University of Washington and UBC Presses, 1999.

Cathlapotle and its Inhabitants, 1792-1860. A report prepared for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 1. Cultural Resources Series #15. Portland, Ore.: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2011, 2015.

“Report of Mr. George Gibbs to Captain Mc’Clellan, on the Indian Tribes of the Territory of Washington.” In Reports of Exploration and Surveys…from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean, vol. 1, 402-49. 33d Cong., 2d Sess., House Exec. Doc. 91, serial 736, 1854. Reprint by Ye Galleon Press, Fairfield, Wash., 1972.

Swan, James. “January 7, 1857, letter on causes of Indian war.” In The Northwest Coast; or three years’ residence in Washington Territory, 425-29. Reprint by University of Washington Press, Seattle, 1972.

Haines, Francis. “The Northward Spread of Horses among the Plains Indians.” American Anthropologist 40 (1938): 429-37.

Gough, Barry, ed. The Saskatchewan and Columbia Rivers. Vol. 2 of The Journal of Alexander Henry the Younger, 1799-1814. Toronto: The Champlain Society, 1992.

1838 Census of Indian Population at Fort Vancouver: Klikitat Tribe, Cathlacanasese Tribe, Cath-lal-thlalah Tribe. Hudson’s Bay Company Archives. Ms. B.223/z/1/, folders 26-28. Winnipeg.

Norton, Helen, Robert Boyd, and Eugene Hunn. The Klickitat Trail of south-central Washington: a reconstruction of seasonally-used resource sites. In Indians, Fire, and the Land in the Pacific Northwest, edited by Robert Boyd, 65-93. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 1999.

Roberts, George. “Letters to Mrs. F.F. Victor, 1878-83.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 63:2 (1962): 175-244.

Records of the Oregon Superintendency of Indian Affairs. National Archives and Records Service.

Records of the Washington Superintendency of Indian Affairs, 1853-74. National Archives and Records Service.