In the 1850s, Apserkahar, also known as Chief Joe, led one of the two principal bands of Native Americans living in the western Rogue Valley. His brother Toquahear led the other band. Apserkahar means Horse Rider and is variously spelled Apserkahah, Apsakahah, and joapserkahar. Most sources refer to his people as Takelmas, although some state that they were Shastas and even Athapaskans.

Historic tribal identities can be tricky, and early written documents are often vague or inaccurate. Many scholars, however, believe that Apserkahar’s band lived at the heart of the Takelma-speaking homeland. The historical record demonstrates that he had close ties to the Shastas (Hokan speakers) in southwest Oregon’s Bear Creek Valley and neighboring California. Native peoples in the region did not figure their primary identity using linguistically defined nations or tribes until formal relations with the United States made it necessary.

Factors such as decentralized polities, common intermarriages among bands and across language groups, and seasonal movements made Indigenous identity more fluid than a fixed “nation” or “tribe” suggests. Strictly defined nations developed partly through treaty signings between 1851 and 1856, when EuroAmericans sought to clear property titles by getting representative signatures from Native peoples in the Rogue Valley. Subsequently, tribes had to use these fixed treaty designations to pursue legal claims against the U.S., and tribal boundaries became matters for the courts.

Apserkahar signed treaties in 1853 and 1854 and likely in 1851. It is not a surprise that both Takelma and Shasta peoples have claimed Apserkahar as an ancestor; Indigenous identities did not mirror those fixed by treaty, and colonization reduced complex resource-use privileges to an imposed system of individual property rights.

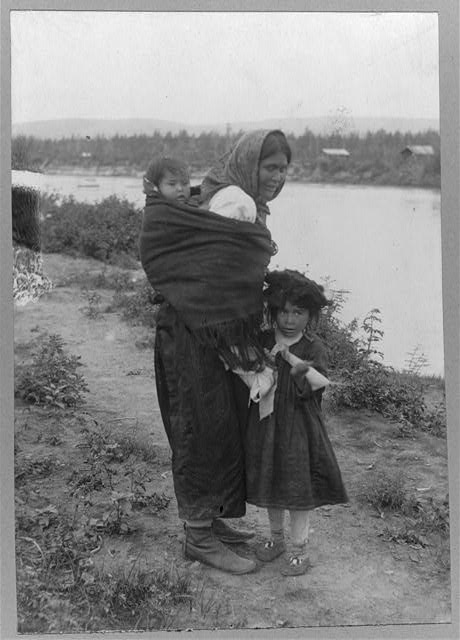

As a headman, Apserkahar held an elevated social status, which he maintained by making sound decisions in the face of imported diseases, raids by miners and other Native people, and taxed resources, as newcomers pressured and altered the local ecology. Apserkahar’s wife, known as Sally to Americans, assisted him, and her views carried considerable weight. The influence of Apserkahar and Toquahear stretched into northern California among Shastas.

Colonial incursions shaped the broad outlines of Apserkahar’s life. By the 1810s, the effects of the Columbia River fur trade and Spanish colonization in California were evident in the Rogue Valley. As a child, Apserkahar would have witnessed the indirect influence of newcomers through fur-trade goods. In addition, Native people from the Columbia River and Klamath Basin raided Takelmas and Shastas for slaves, using horses and guns acquired from newcomers.

By 1851, when the California Gold Rush spilled into his homeland, Apserkahar knew to take a cautious and conciliatory approach to Americans, who referred to his people and their neighbors as “Rogues” and exaggerated the occurrence of occasional interracial violence. In 1850, former Territorial Governor Joseph Lane had accused Apserkahar’s band of robbing a party of miners. Lane’s group captured Apserkahar and compelled an uneasy arrangement from him, which allowed for the peaceful passage of future emigrants and miners in exchange for periodic gifts. Apserkahar found the guilty man, killed him to prevent further bloodshed, and recovered as much of the stolen goods as he could. Lane claimed that Apserkahar requested an American name and was pleased with sharing the name Joe.

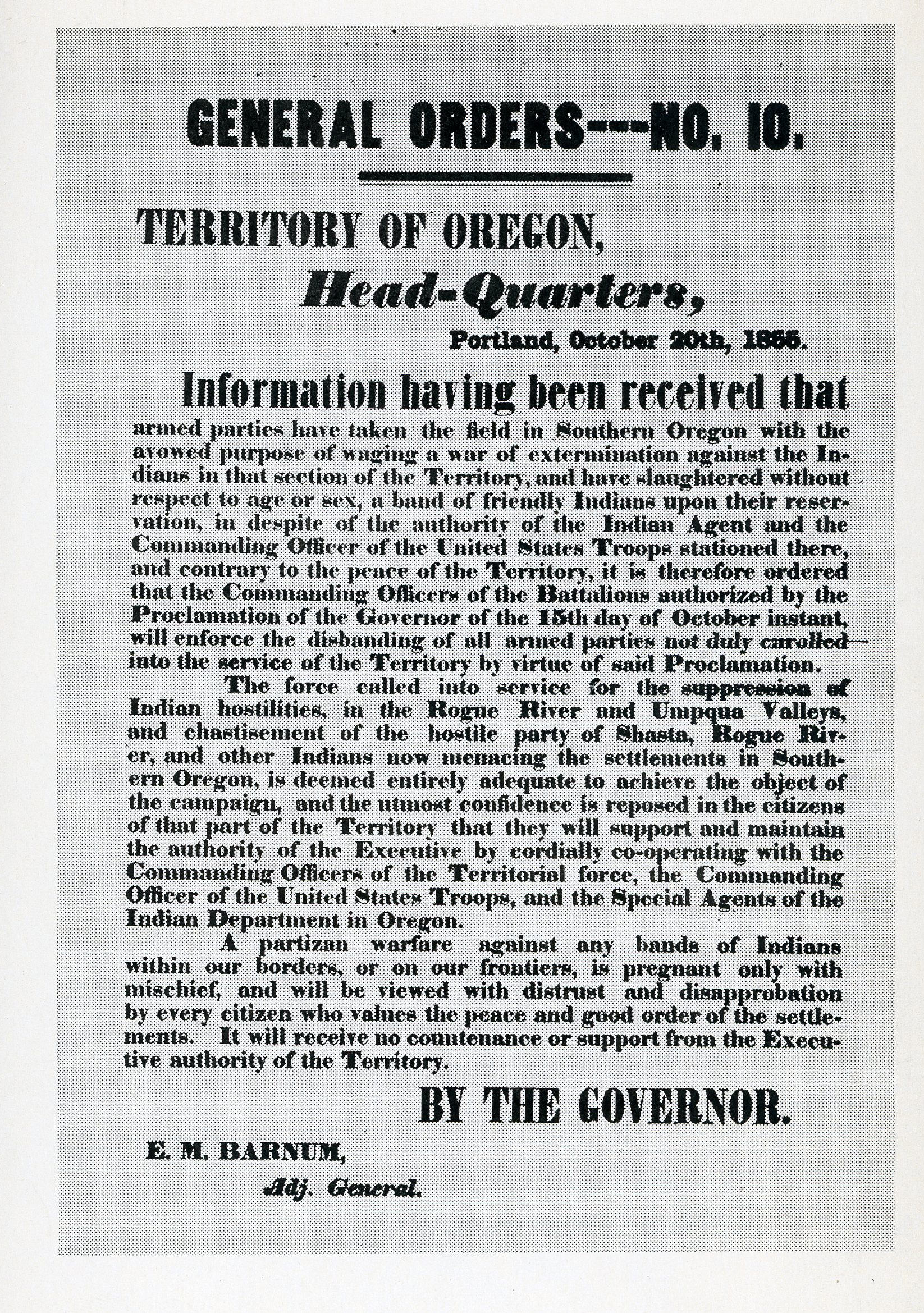

Following a brief conflict in 1853, Lane captured Apserkahar’s children, Mary and Ben, to compel Apserkahar to sign the Table Rock Treaty. In 1854, as Apserkahar lay dying of tuberculosis, he ceded more territory to the United States in an attempt to protect his people and homeland. Nevertheless, the Rogues faced another war with the U.S. Army in 1855, which resulted in the forced removal of most of the Native survivors in February-March 1856 to the Grand Ronde and Coast (later Siletz) Reservations.

-

![]()

Rogue River.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., Org Lot 369, FinleyB1024

-

![]()

Table Rock, 1887.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 003842

Related Entries

-

![Athapaskan Indians]()

Athapaskan Indians

According to Tolowa oral histories, the Athapaskan people of southern O…

-

Coast Indian Reservation

Beginning in 1853, Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer negotia…

-

![Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde]()

Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon is a confede…

-

![Council of Table Rock]()

Council of Table Rock

The 1853 Council of Table Rock negotiated a peace treaty between repres…

-

![Rogue River War of 1855-1856]()

Rogue River War of 1855-1856

The final Rogue River War began early on the morning of October 8, 1855…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Beckham, Stephen Dow. Requiem for a People: The Rogue Indians and the Frontiersmen. Corvallis, Ore.: Oregon State University Press, 1971.

Heizer, Robert F. and Thomas Roy Hester. “Shasta Villages and Territory.” Contributions of the University of California Archaelogical Research Facility: Papers on California Ethnography 9 (1970): 119-158.

Schwartz, E.A. The Rogue River War and Its Aftermath, 1850-1980. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997.

Whaley, Gray H. Oregon and the Collapse of Illahee: U.S. Empire and the Transformation of an Indigenous World, 1792-1859. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2010.