Situated in the Columbia River Gorge about sixty miles east of Portland, the City of Hood River occupies a transition zone between temperate, wet western Oregon and the dry, high plateau of eastern Oregon. The city, which had a population of about 8,313 people in 2020, shares its name with the Hood River, which plummets twenty-five miles north from Mount Hood through the Hood River Valley to the Columbia River.

For millennia, the Columbia River Gorge served as a sea-level passage through the Cascade Mountains. Salmon passed through to reach their spawning grounds, attracting the Wasco, Warms Springs, and Watlalas people to the area. Strong winds funnel through the Gorge, and the area endures a nearly constant, typically upriver, summer breeze. While the wind helped Native peoples dry their salmon catches efficiently, it would prove a nuisance for most white residents.

Hood River found a place on William Clark’s map as Labeasche River, after expedition member François Labiche, but the name did not stick and the stream came to be known as Dog River. Nathaniel Coe claimed land near the mouth of Dog River in 1854, building a house and planting the first orchard; his wife Mary rechristened the stream Hood River. A small but prosperous settlement developed, formally incorporating in 1895. Logging and agriculture dominated the local economy, as loggers harvested the trees and orchardists employed Japanese immigrants to remove the stumps and clear land.

Steamboats, the arrival of the Oregon Railroad & Navigation Company’s first train in 1882, and the completion of the Columbia River Highway in 1915 enabled the development of market-oriented agriculture. Apples, which could be packed and shipped, provided the foundation of commercial horticulture, and pears were introduced following the hard winter of 1919-1920. On June 23, 1908, the City of Hood River and the surrounding area separated from Wasco County to form Hood River County. By 1910, the new county had a population of 8,016, including 468 Japanese and Japanese American residents.

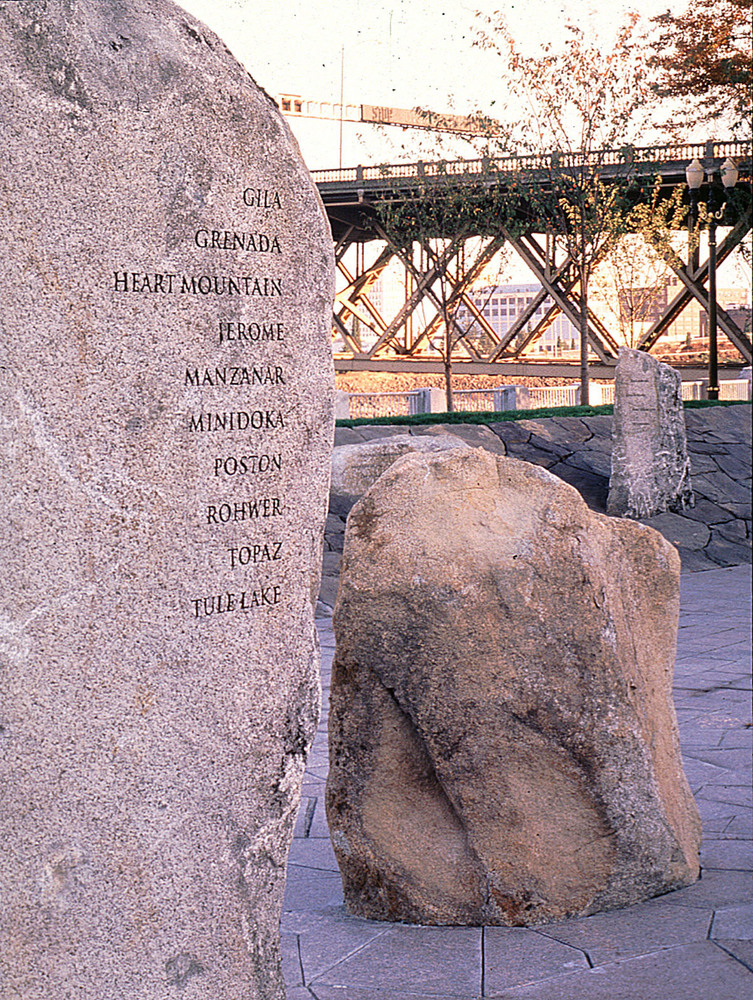

World War II and presidential Executive Order 9066 were disastrous for Hood River Japanese and Japanese Americans who were imprisoned in camps throughout the West. Former Hood River resident Minoru Yasui unsuccessfully challenged the legality of the government’s relocation order in Portland in federal court in United States of America v. Minoru Yasui, heard by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1943. After the war, the city’s Japanese and Japanese American residents, who had about three-quarters of their land taken from them because of the war, rebuilt their lives despite widespread discrimination. Many Hood River businesses posted signs declaring “No Japs Wanted.”

During the late twentieth century, Hood River experienced profound changes, as the horticulture industry grappled with changing consumer tastes and logging companies faced a weak housing market. By 1990, the high costs of retooling sawmills to cut smaller logs, the export of unmilled logs, and the listing of the Northern Spotted Owl as an endangered species put smaller sawmills at a competitive disadvantage. Many smaller mills, such as Hood River’s Hanel Lumber, sold out or folded. Horticulture survived, in part because of low-paid labor from Mexico and Latin America (Hood River County has one of the highest percentages of Hispanic residents in Oregon, at 29.5 percent).

Low-paying service jobs, especially in tourism, replaced lost jobs in extractive industries. In the early 1980s, sailboarders arrived to take advantage of the Gorge winds and the depressed local economy. While tourism had long been a part of Hood River’s economy—hotels such as Cloud Cap Inn (1889) and the Columbia Gorge Hotel (1920) were popular—it would not dominate the local economy until the 1990s. By 1999, Hood River had over thirty windsurfing equipment suppliers, more than all the other Gorge towns combined. The county’s 1980 population was 15,835, but grew by almost a quarter to 20,411 by 2000. Newcomers drove home values up, pricing some long-time residents out of the community.

Tourism’s importance is reflected in the county’s many art galleries, wineries, breweries, festivals, and events. Hood River’s proximity to Portland helped the county augment tourism jobs with employment in technology and telecommunications. In 1986, the Port of Hood River remodeled the abandoned Diamond Fruit Cooperative cannery into the Waucoma Center, attracting a Sprint call center. More recently, the defense Hood Technologies located its headquarters in Hood River.

The federal government plays an important role in the county, managing the Mount Hood National Forest and Bonneville Dam at nearby Cascade Locks. The Columbia Gorge National Scenic Area, created in 1986, requires government agencies, local municipalities, and other interest groups to cooperate on issues of economic development, urban sprawl, and the conservation of cultural and environmental resources.

-

![]()

Oak Street, Hood River, c.1910.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Gi1128

-

![]()

Oak Street, Hood River.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi1620a

-

![]()

Hood River train depot, c. 1910.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi56064

-

![]()

Columbia Gorge Hotel, 1923.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 007280

-

![]()

Columbia Gorge Hotel, 1923.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 007279

-

![]()

Hood River, Oregon, 1929.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 371, box 2, f9

-

![]()

Hood River Valley apple orchards.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi75017

-

![]()

Aerial view of Hood River, 1930.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi85748

-

![]()

Aerial view of Hood River, 1931.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 000973

-

![]()

Mitchell Point, Columbia River Highway, west of Hood River.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Gi6560

-

![]()

Mitchell Point, Columbia River Highway, west of Hood River.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Gi6552

-

![]()

Apple Growers Assoc. warehouse, Hood River.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Gi8030

-

![]()

Hood River and the Columbia River Highway.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Gi7883

-

![]()

Bonneville Dam, 1936.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 002652

-

![]()

Aerial of Bonneville Dam.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 019501

-

![]()

Looking west at Hood River and construction on new I 84 freeway, 1952.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 000972

Related Entries

-

![Cloud Cap Inn]()

Cloud Cap Inn

Cloud Cap Inn stands at nearly 6,000 feet on Mount Hood's northeastern …

-

![Frank Hachiya (1920-1945)]()

Frank Hachiya (1920-1945)

The name Frank T. Hachiya will forever be linked to Oregon’s Hood River…

-

![Full Sail Brewing Company]()

Full Sail Brewing Company

Founded in 1987 in Hood River, the Full Sail Brewing Company is one of …

-

![Hood River Distillers]()

Hood River Distillers

Hood River Distillers, Inc., received the first state distiller's licen…

-

![Japanese Americans in Oregon]()

Japanese Americans in Oregon

Immigrants from the West Resting in the shade of the Gresham Pioneer C…

-

![Japanese American Wartime Incarceration in Oregon]()

Japanese American Wartime Incarceration in Oregon

Masuo Yasui, together with many members of Hood River’s Japanese commun…

-

![Kenneth Jernstedt (1917–2013)]()

Kenneth Jernstedt (1917–2013)

Pilot and legislator Ken Jernstedt was known as the “First Ace Ever” fo…

-

![Minoru Yasui (1916–1986)]()

Minoru Yasui (1916–1986)

Minoru Yasui was born in Hood River on October 16, 1916, the third son …

-

![Port of Hood River]()

Port of Hood River

Since its incorporation in July 1933, the Port of Hood River gradually …

-

![Sherman Burgoyne (1901-1964)]()

Sherman Burgoyne (1901-1964)

Until he arrived in Hood River in 1942, William Sherman Burgoyne had ne…

-

![Shizue Iwatsuki (1897–1984)]()

Shizue Iwatsuki (1897–1984)

A humble wife, mother, and public servant in Hood River, Shizue Iwatsuk…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Moulton, Gary E. The Definitive Journals of Lewis and Clark. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2002.

Hood River County Historical Society. History of Hood River County, Oregon: 1852-1987. Dallas, Ore.: Taylor Publishing Company, 1987.

Tamura, Linda. The Hood River Issei: An Oral History of Japanese Settlers in Oregon’s Hood River Valley. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994.

Kessler, Lauren. Stubborn Twig: Three Generations in the Life of a Japanese American Family. New York: Random House, 1993. on H.

Hill, Cheryl. The Mount Hood National Forest. Charleston: Arcadia Publishing Co., 2014.

Abbott, Carl, Sy Adler, and Margery Post Abbott. Planning a New West: The Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area Act. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 1997.