The joint appearance in 1927 of the controversial pamphlet Status Rerum by writers H.L. Davis and James Stevens and the new regional magazine Frontier edited by H.G. Merriam signaled a notable transition in the literary history of Oregon. These two publications pointed to—even denounced—the inadequacy of Oregon and Pacific Northwest writing. They also helped prepare the way, as Local Color writers of the late-nineteenth century had, for the regional flood that was beginning to wash over the Far Corner and other parts of the United States.

For Davis and Stevens, earlier Oregon authors, as well as contemporary writers and teachers, were too timid and too tied to outmoded and alien cultural standards. The so-called literary lions were toothless frauds, they charged, nothing but "posers, parasites, and pismires" unable to "pile lumber,…shear sheep, or castrate calves." For Merriam, writers of the Pacific Northwest had to discover their region, understand its cultural rhythms, and work these experiences and ideas into their regional writing.

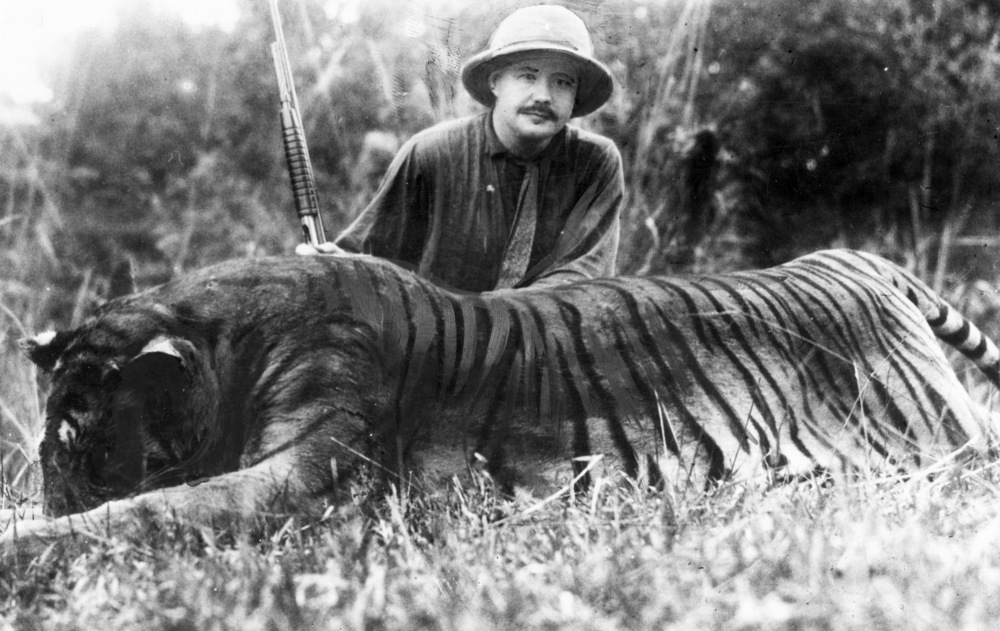

As the regionalists were attempting to redirect Oregon literature, other writers of more romantic tendencies continued to publish their works in the early-to-mid-twentieth century. The writings of these authors were more akin to the earlier romances of Oregon writers Frederic Homer Balch and Eva Emery Dye than to the fiction of the regionalists. Among these were Ella Higginson, a writer of Local Color stories set in Oregon and Washington, whose best-known novel was a historical romance entitled Mariella; of Out-West (1904). Much more bombastic and spread eagle were the historical novels of Edison Marshall, who, Hemingway-like, traveled the world as a big-game hunter in search of stirring historical narratives. Of his dozens of novels, Benjamin Blake (1941) won wide attention and was made into a movie.

The most enigmatic of the nonregionalists was Opal Whiteley, a shy, reclusive young woman from Cottage Grove. When her romantic, ethereal autobiography, Opal: The Journal of an Understanding Heart (1920), first appeared serially in the Atlantic, it captivated nationwide audiences with its unlikely tale of the heroine being spirited away from French royalty and taken to an Oregon lumber camp. The controversies surrounding the journal's origins and Opal's credulity-stretching story of her earliest memories have detracted readers from the strengths of Whiteley's romantic, child-like treatments of animals and nature. She was Oregon's Girl of the Limberlost.

Of the rising regionalists, H.L. Davis practiced what he preached in Status Rerum. He proved to be the exemplar of the regionalism that invigorated Oregon literature of the 1930s and 1940s. His Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Honey in the Horn (1935), the only Oregon novel to garner that award, brims with pungent descriptions of Oregon settings and lively characterizations. A sprawling picaresque work, almost without plot, it revealingly portrays the Oregon countryside and overflows with a panoply of rural people. Davis showed how experiences over time had shaped—even skewed—the lives, communities, and work patterns of Oregonians.

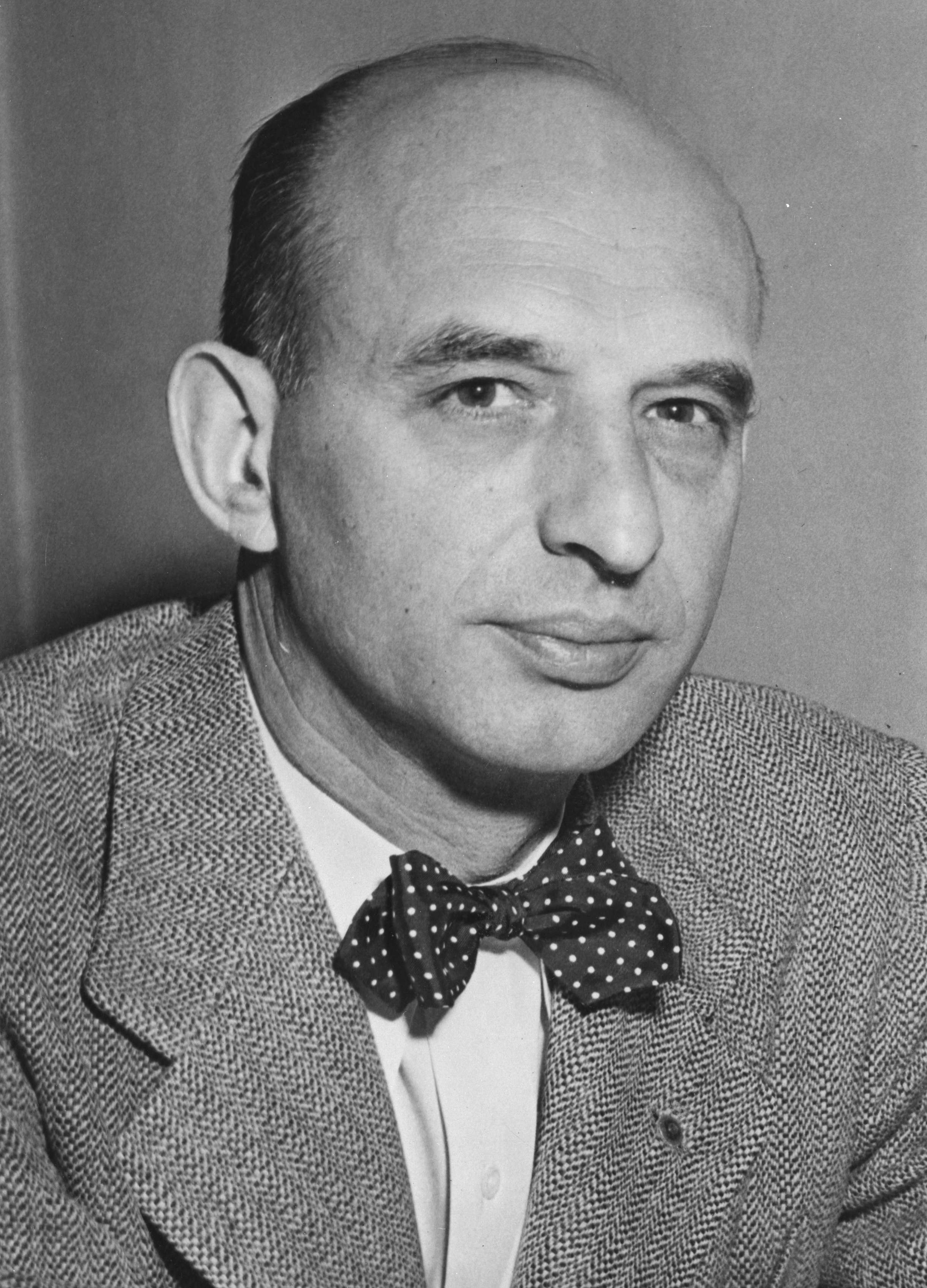

James Stevens and Nard Jones were two other important regionalists in the first half of the twentieth century. Stevens, reared on Northwest farms and in logging camps, became a defender of working-class stiffs, gained the attention of America's leading cultural critic H.L. Mencken, and won acceptance in Mencken's influential literary-cultural magazine, the American Mercury, in the 1920s. In Paul Bunyan (1925) and Big Jim Turner (1948), Stevens celebrated the regional life of loggers, hoboes, biddle stiffs, and miners.

At the beginning of the 1930s, Nard Jones set residents of his hometown of Weston on their ears with his first novel, Oregon Detour (1930). A work of realistic regional fiction par excellence, with revealing handling of sexuality, teenager angst, and small-town smugness, the novel immediately drew Oregon readers and gained Jones critical attention. He followed with another contemporary and realistic novel, Wheat Woman (1933), and then turned to such historical novels as Swift Flows the River (1940) and Scarlet Petticoat (1941), which sold much better than his regional novels.

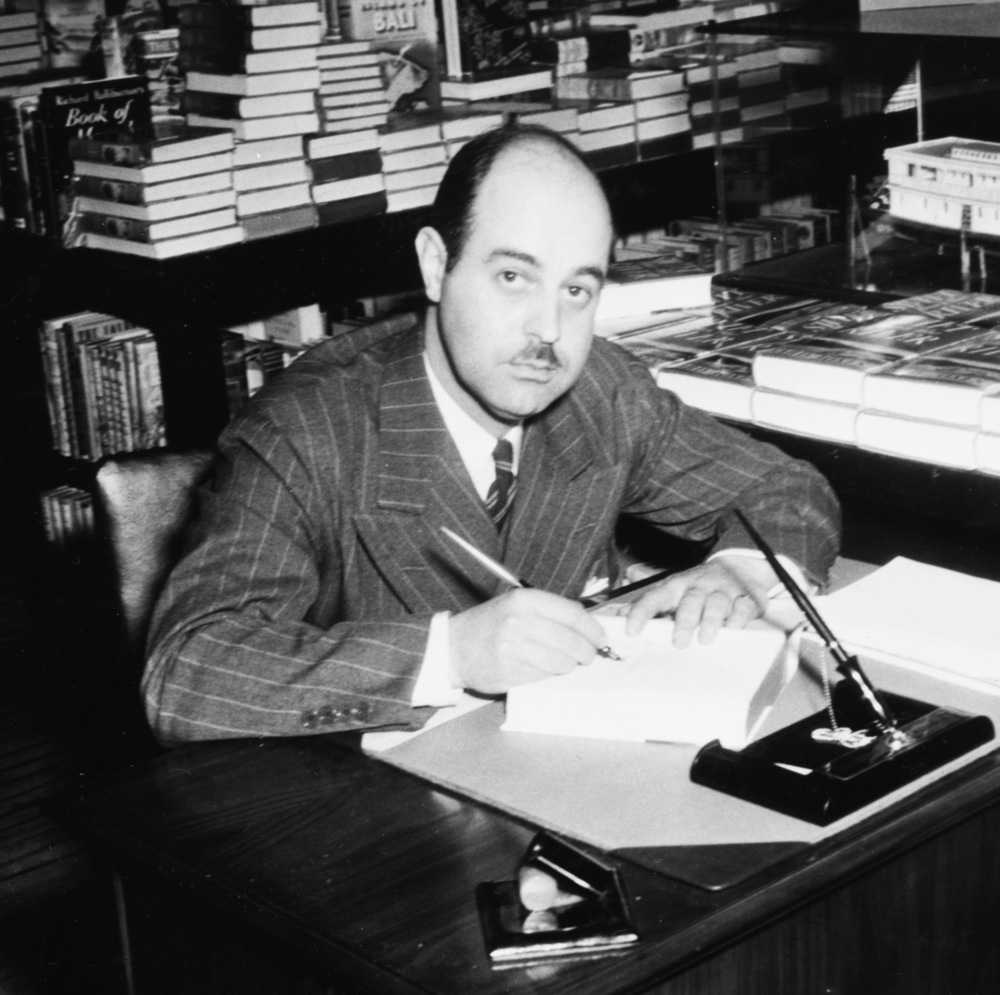

Not all Oregon writers joined the regional camp, however. Ernest Haycox, the most financially successful Oregon writer of his time and author of 23 novels and nearly 300 serial installments and short stories, initially stoutly avoided the regionalists. Deciding early on to write formulaic western fiction, Haycox served his apprenticeship in the New York City pulp magazines of the 1920s and then became part of the stable of serial writers for slick magazines such as Collier's and Saturday Evening Post. Toward the close of his career in the 1940s, he attempted to break from the Western formula to produce regional fiction. Bugles in the Afternoon (1944) moved in that direction, but his posthumously published The Earthbreakers (1952) remains his strongest novel. Other writers such as Wayne Overholser, Charles Alexander, and Robert O. Case turned out dozens of Westerns but failed to gain the attention or accolades of Haycox. Much later, the prolific Jane Kirkpatrick followed in this tradition with her enormously popular historical and Christian fiction.

Beginning in the 1960s but even more so afterward, many Oregon authors moved beyond regionalism in their fiction and poetry. Although post-1960s writers did not fully abandon the central tenet of regionalism—the forming power of place on character—they added new ingredients that moved their writings in path-breaking directions.

Postregionalists displayed a number of writerly tendencies that were at variance from the regionalists. Rather than put primary emphases on place-shaping-character themes, postregionalists stressed gender, race and ethnicity, environment (ecology), or other subjects. Place was not forgotten but became less central to their writings.

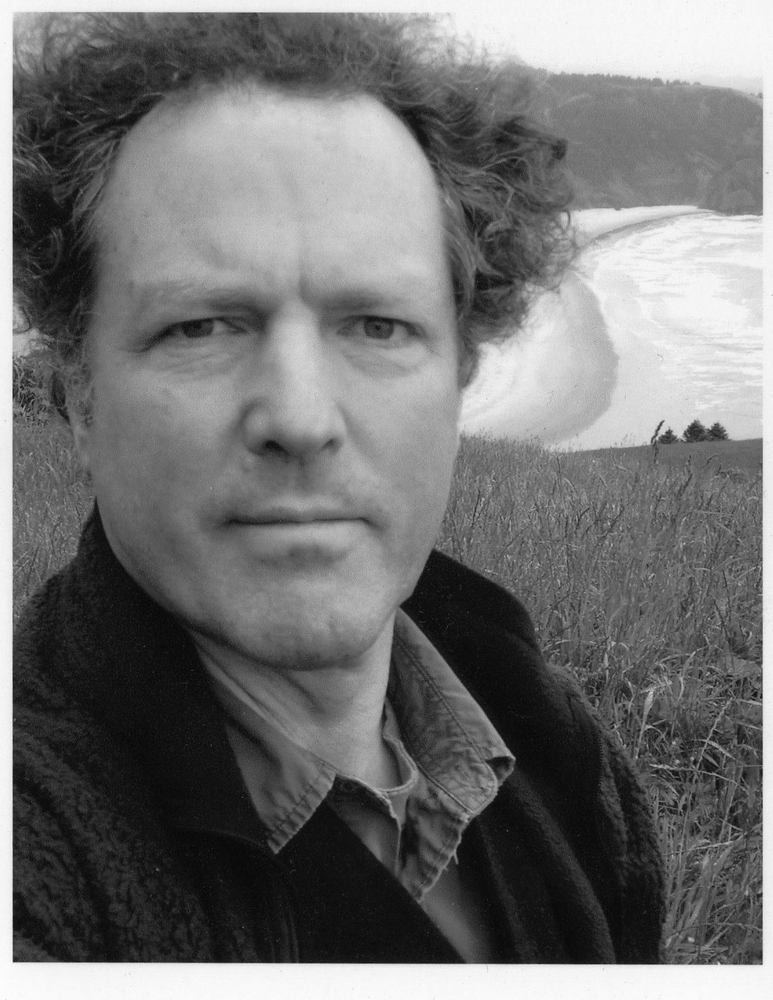

Some of these fresh emphases broadened Oregon literature, including new treatments of Native American experiences. Novelist Craig Lesley in Winterkill (1984) and River Song (1989), and poet Elizabeth Woody in Hard Into Stone (1988) and Seven Hands, Seven Hearts (1994), for example, dealt with Indian pasts that regionalists such as H.L. Davis overlooked or that writers of popular Westerns limited to barbaric or rather pathetic opponents. Like most other writers in the American West, non-Indian and Indian authors in Oregon did not people their fiction and nonfiction with Native American characters until the 1970s.

Other postregional writers stressed gender themes. One of the most impressive of these novelists was Molly Gloss, who creatively reinterpreted the male frontier stories of homesteading and cowboying to show how women's roles were central to those experiences. In The Jump-Off Creek (1989) and The Heart of Horses (2007), readers found in Gloss's appealing western fiction a corrective view—the strong but balanced presentation of women's pivotal participation in the western past, a topic that too many male writers had overlooked.

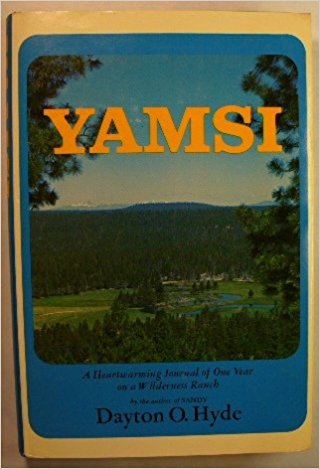

Other Oregon writers took more explicit and penetrating looks at the environment. The new environmentalists became strong voices for preservation and wilderness advocacy and were critical of the less committed. William Kittredge harpooned what he considered greedy and destructive ranchers and developers in Hole in the Sky (1992) and Who Owns the West (1995), while Barry Lopez moved in other directions with his strongly worded accounts of human-animal relationships in Of Wolves and Men (1978). Dayton Ogden Hyde followed similar paths in his books Yamsi (1971), The Last Free Man (1971), and Don Coyote (1986), celebrating people-land unions, lamenting the ill treatment of Native Americans, and embracing mutual human-animal influences.

In less critical and more positive fashion in his environmentalism, Oregon's most prolific and honored poet, William Stafford, provided expansive views of landscape and place. In his early collection Traveling Through the Dark (1962) and in his later gathering Stories That Could Be True (1977), Stafford juxtaposed setting and people, scene and human emotion, outer and inner terrains. Through his quiet, Robert Frost-like and sometimes disarmingly minimalistic poetry, Stafford captured national attention as a front-rank poet.

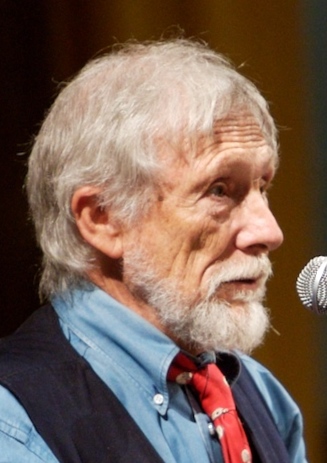

Another Oregon poet, Gary Snyder, also used environmental themes, but in a much different manner from Stafford. In his early years living in Portland, attending Reed College, and working in the woods and at the Warm Springs Reservation, Snyder imbibed a strong sense of varied physical and cultural landscapes. Later, after diligent study of Buddhist teachings and connections with several Beat writers, he produced numerous collections of poetry illustrating his complex and changing worldviews. In his earlier collections, including Riprap and Cold Mountain Poems (1959, 1965), The Back Country (1968), and Turtle Island (1974), Snyder embraced the wisdoms of primitive, Native American, and Far Eastern societies, particularly their land ethic and sustaining, communal rhythms. Snyder is the only Oregon poet to win a Pulitzer Prize, with his spare and laconic style and environmentally rich themes particularly attractive to readers from the 1960s onward.

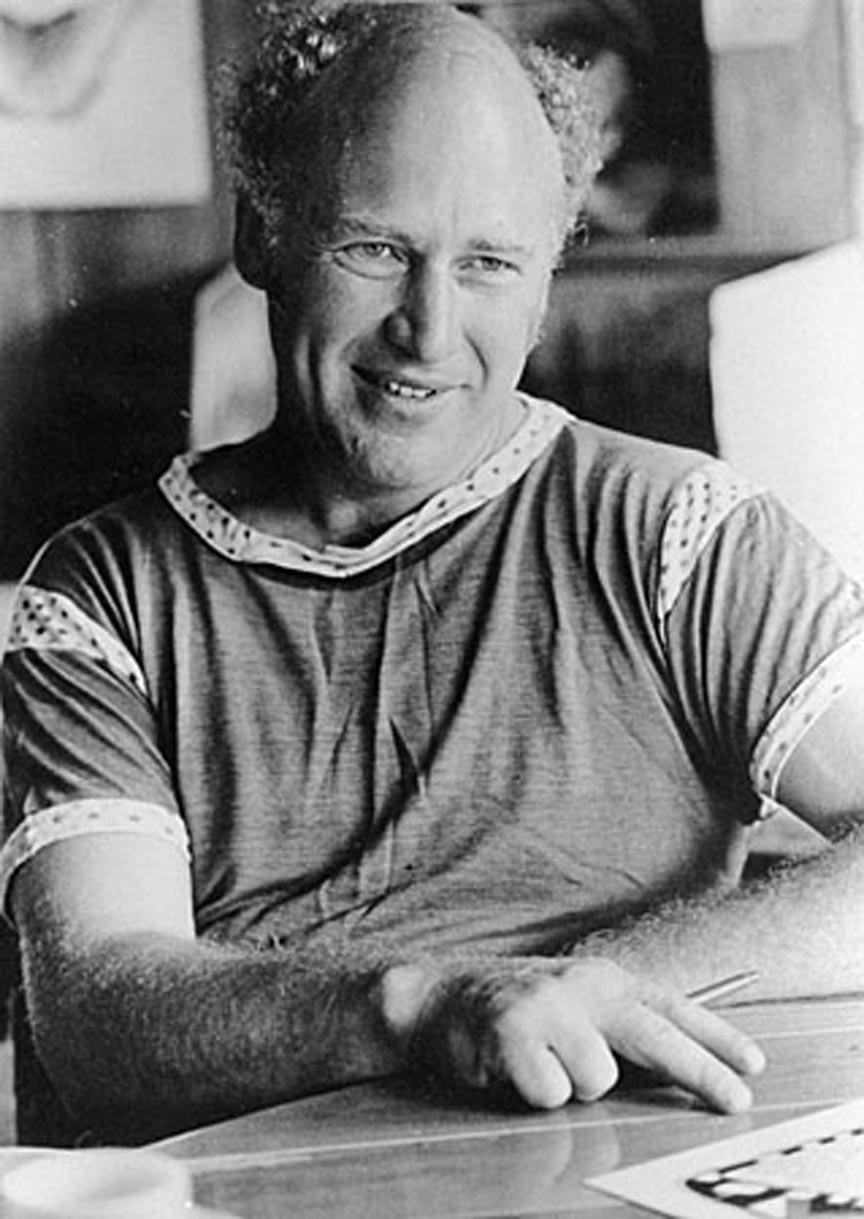

Two Oregon novelists, Ken Kesey and Don Berry, kept their feet in both regional and post-regional camps. Kesey's Sometimes a Great Notion (1964) revealingly renders a redolent region, overflowing with superb depictions of Oregon waterways, a small town, and logger life, as well as their sculpting force on the protagonists' personalities, actions, and outlooks. His brawling gypo loggers—independent, irascible, and profane—fight off nature's pressures and tussle with one another. In its narrative and analytic power, Kesey's masterpiece rivals H.L. Davis's Honey in the Horn as Oregon's premier regional novel.

Conversely, Kesey's One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest (1962) represents another kind of Oregon fiction. The novel, set in the state, includes an oceanside interlude and furnishes glances of an Indian perspective through the fictional character of Chief Bromden, but the novel primarily dramatizes a social madhouse and gender civil war taking place in the state's insane asylum. Captained by indefatigable Randle Patrick McMurphy (RPM, unforgettably played by Jack Nicholson in the movie version), the men take aim at Big Nurse in the battle to control the institution. Black orderlies, wives, and girlfriends are shouldered aside in the fight to operate the control room and to keep the Combine and "fog machine" (corporate power and the federal bureaucracy) at bay. In its fascination with race, gender, and class, Kesey's enormously popular novel illustrated the main ingredients of postregional literature that infiltrated Oregon writing in the post-1960s period.

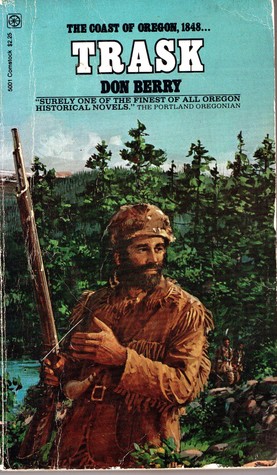

The same curious bifurcation is obtained in two of Don Berry's novels. Berry's first Oregon novel, Trask (1960), follows trapper Elbridge Trask through his journeyings in early Oregon. Including marvelous depictions of settings and scenes, the novel is nonetheless more about Trask's inner than outer landscapes. His Zen-like pilgrimage traversing the northwest corner of Oregon resembles the "search" toward maturity and understanding so popular among Native American males. On the other hand, Berry's second novel, Moontrap (1962), more closely resembles classic regional novels in its emphases on natural, social, and cultural terrains that shape the lives and actions of newly arrived mountain men. In the title-producing scene, Old Webb, a refugee to the Oregon City area at the end of the fur trade, tries to trap the shadow of the moon in an alpine stream. He fails, just he has been unable to stop the inexorable passing of time in his own life. Suffering defeat, he flails out at an opposing society by killing one of its preachers. Similar ostracism attacks a young trapper in the novel who has taken up with a young Indian woman; he, too, is held off by an unaccepting society, a move that leads to another tragedy. Berry's regional novel movingly depicts an Oregon Country in which a nascent culture destroys those who challenge its prejudicial prescriptions.

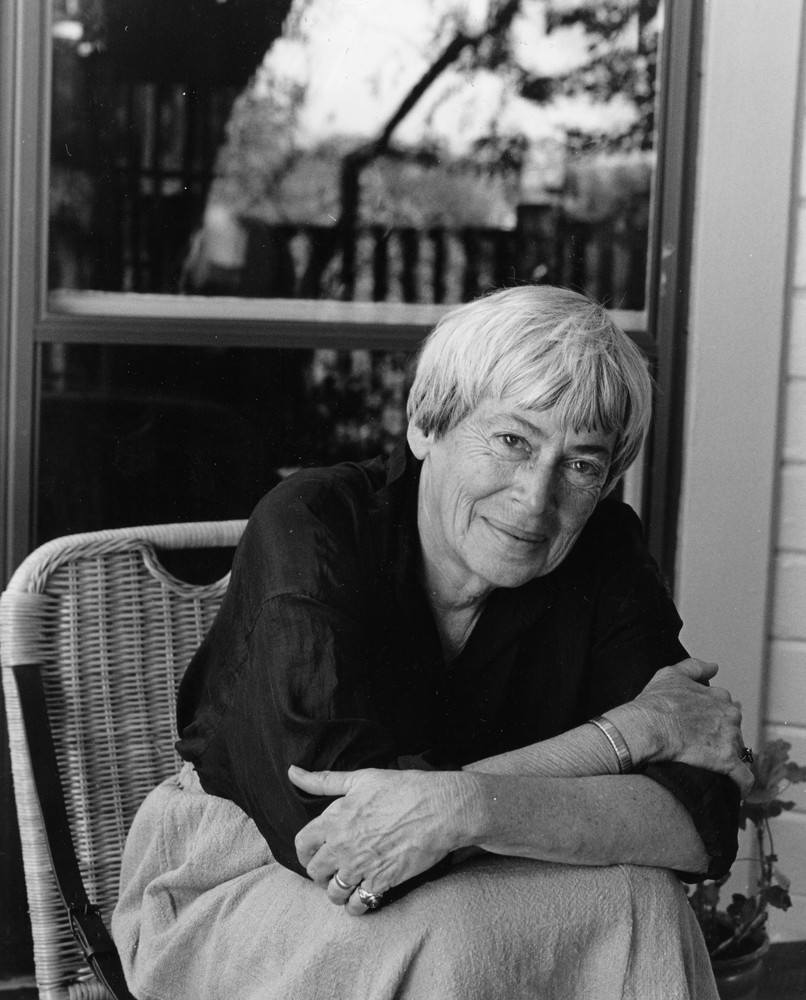

Not all writers can be pigeonholed as regional or postregional. The most widely honored of Oregon's nonregional writers is Ursula Le Guin. She is an internationally celebrated writer of science fiction and other genres, including her early works The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) and The Dispossessed (1974), both of which won Hugo and Nebula awards. Her fantasy novels, including the Earthsea cycle, have also won numerous prizes. The daughter of anthropologist Alfred Kroeber and psychologist and writer Theodora Kroeber Quinn, Le Guin infused her fiction with insights from cultural anthropology and psychology and an overlay of interests in feminism and race. Her more than fifty books, most of which are set outside the American West, have garnered many awards, including the National Book Award.

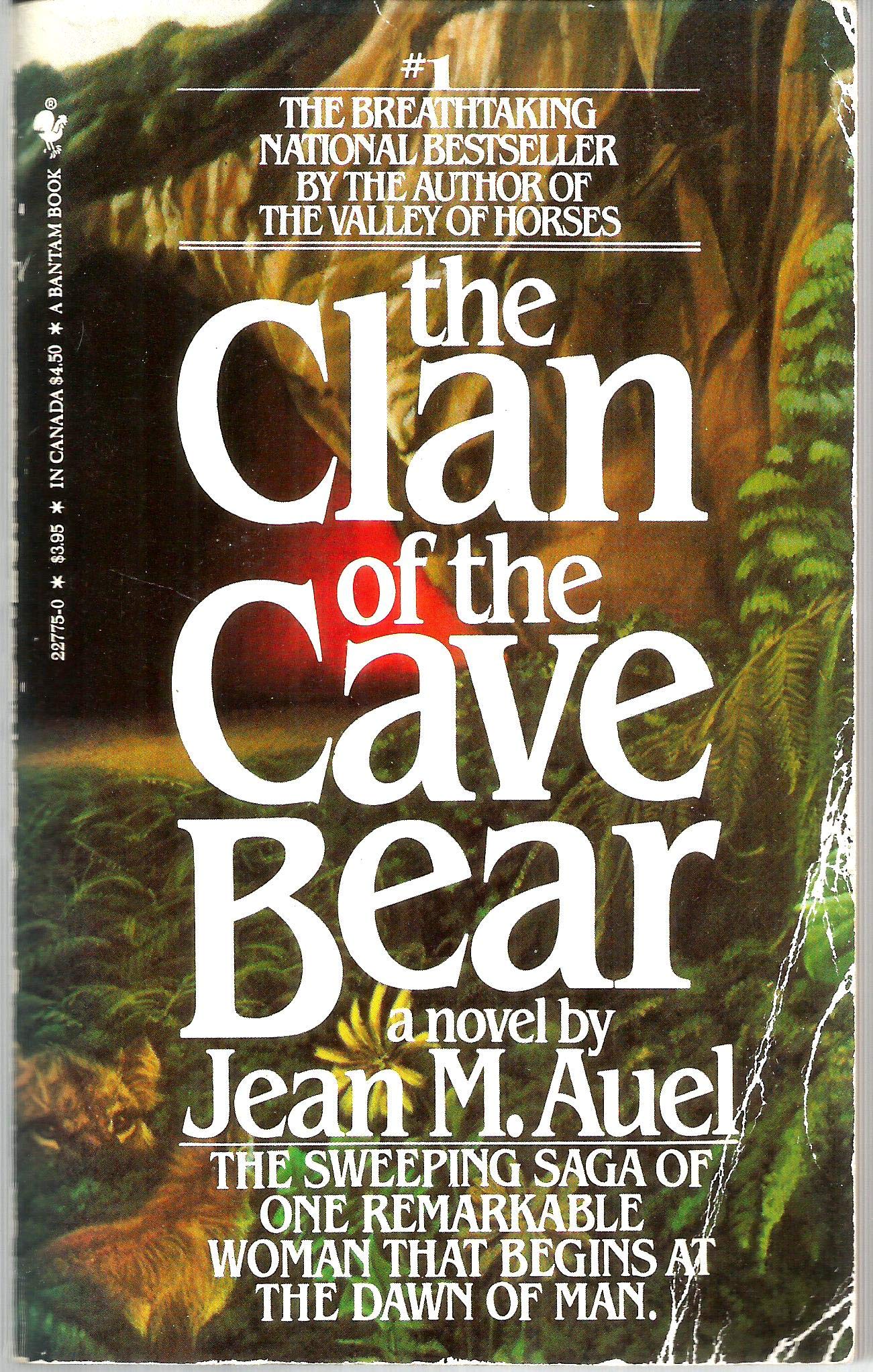

Other Oregon nonregional writers have also gained wide readerships. Jean Auel won best-seller status for her novels about prehistoric young women. And how can one categorize the wildly successful best-sellers that Richard Brautigan, the hippie troubadour, penned in Trout Fishing in America (1967) and The Hawkline Monster (1974), or the nihilistic novels of Chuck Palahniuk such as Fight Club (1996)—viciously violent works containing little of Oregon. Taken together, or separately, these and many other writers of fiction and their works testify to the appealing diversity of recent Oregon literature.

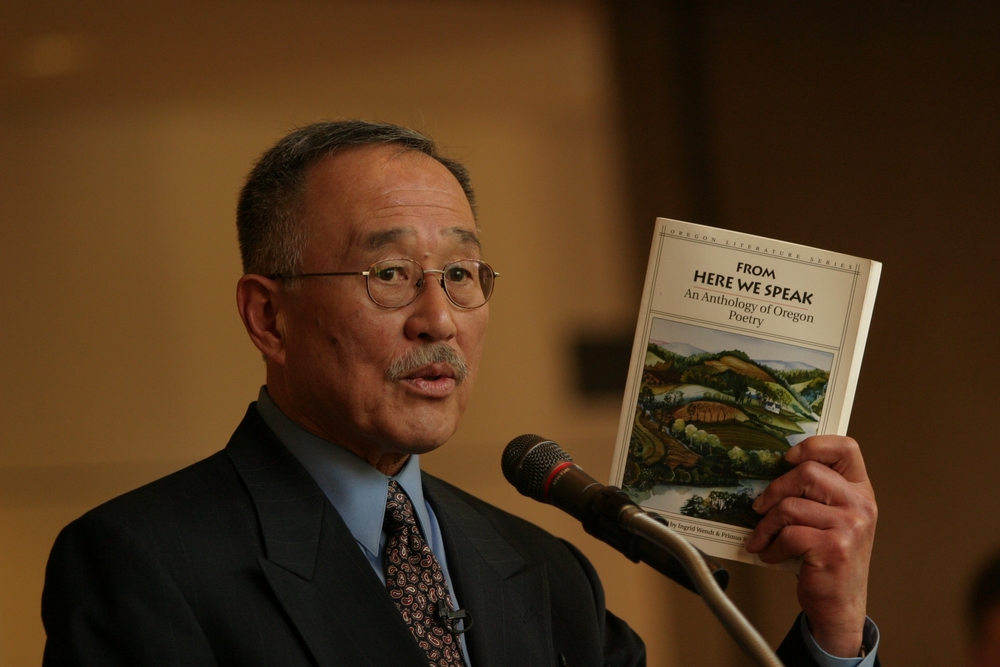

Similar diversities characterize the writings of Oregon poets throughout the twentieth century. Early in the century, recluse Hazel Hall garnered national attention for her quiet, Emily Dickinson-like poems that revealed much about her inward sky at much the same time that H.L. Davis won a major award and high praise from poetry maven Harriet Monroe for his Oregon poetry. Later, racial and ethnic themes became even more notable in the writings of Oregon Japanese American writer Lawson Inada, African American Primus St. John, and Native American Elizabeth Woody. Currently, Kim Stafford, son of William Stafford, has gained an expanding reputation for his poetry and nature writing. Some of these poets and still other writers found the Northwest Review on the campus of the University of Oregon a welcoming and sustaining outlet for their work.

By the early twenty-first century, Oregon literature had gained a new maturity. Having moved through its frontier and regional periods, it was now well into what literary historian Glen A. Love calls its "international and multicultural" stage—what is designated here as its postregional era. This development meant that writers, over time, had learned how space became place and then could be something beyond Oregon even if it was written in the state. Regional and post-regional writers, in jostling one another for dominance, illustrated the appealing diversity and ever-changing quality of the state's rich and complex literary history.

-

![]()

Ursula LeGuin, by Marian Wood Kolisch.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org. Lot 1078, OSA 1, folder 3

-

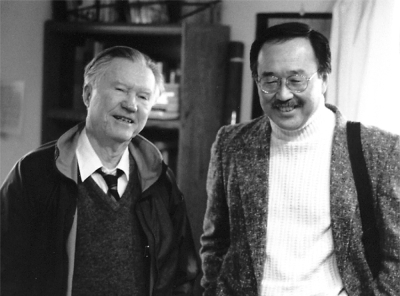

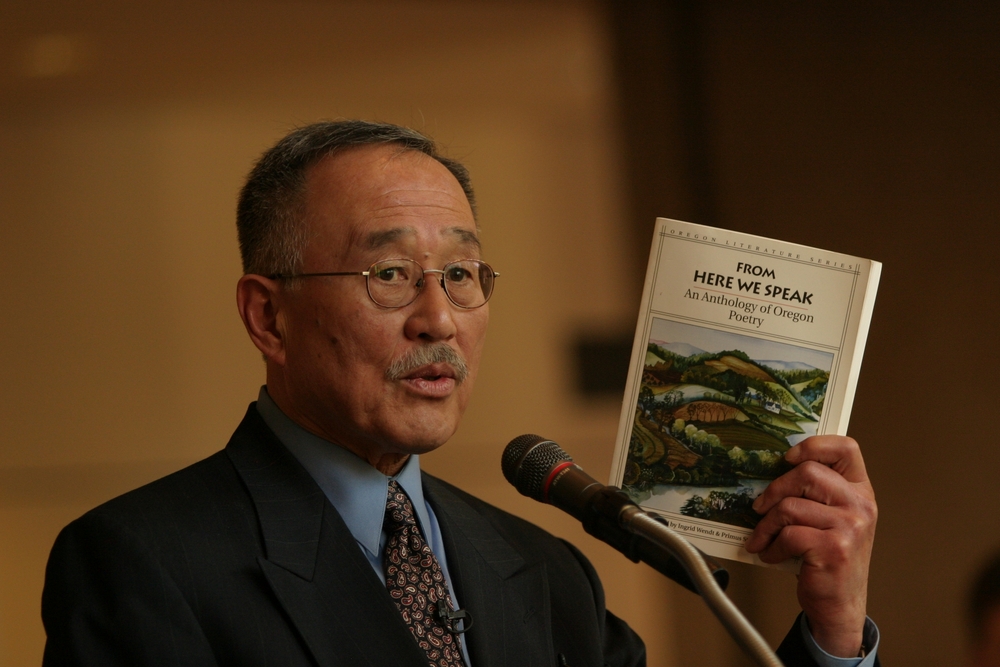

Poet Lawson Inada (r) with William Stafford.

Copyright www.poetryvideos.com

-

![Hazel Hall.]()

Hall, Hazel, OrHi 77466.

Hazel Hall. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Libr., OrHi 77466

-

![Carl Sandberg with other Oregon writers, with James Stevens at far left, Corvallis, Feb. 1927.]()

Sandberg, Carl, with OR writers, Feb 1927, bb007585.

Carl Sandberg with other Oregon writers, with James Stevens at far left, Corvallis, Feb. 1927. Photo Charles O. Olson, Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Libr., bb007585

Related Entries

-

Chuck Palahniuk (1962-)

Fiction writer and journalist Chuck Palahniuk (pronounced paula-nick) w…

-

![Craig Lesley (1945-)]()

Craig Lesley (1945-)

In both his fiction and nonfiction, writer and teacher Craig Lesley spe…

-

![Dayton Ogden Hyde (1925-2018)]()

Dayton Ogden Hyde (1925-2018)

Dayton O. “Hawk” Hyde has been a rancher, naturalist, environmentalist,…

-

![Don Berry (1932–2001)]()

Don Berry (1932–2001)

Don Berry holds a special place in the history of the arts in Oregon. H…

-

![Edison Marshall (1894-1967)]()

Edison Marshall (1894-1967)

Edison Marshall was a nationally known author and adventurer who once t…

-

![Elizabeth Woody (1959-)]()

Elizabeth Woody (1959-)

Poet and artist Elizabeth Woody was named Oregon Poet Laureate in 2016,…

-

![Ella Rhoads Higginson (1862?–1940)]()

Ella Rhoads Higginson (1862?–1940)

Ella Higginson’s writings, especially her prose, were provocative examp…

-

![Ernest Haycox (1899-1950)]()

Ernest Haycox (1899-1950)

Ernest Haycox was an important figure in the development of the popular…

-

![Gary Snyder (1930-)]()

Gary Snyder (1930-)

Many think of Gary Snyder, Pulitzer Prize-wining poet and essayist, as …

-

![Harold Lenoir Davis (1894-1960)]()

Harold Lenoir Davis (1894-1960)

Born and raised in rural and small-town Oregon, Harold Lenoir Davis was…

-

![Hazel Hall (1886-1924)]()

Hazel Hall (1886-1924)

Hazel Hall was recognized in the early decades of the twentieth century…

-

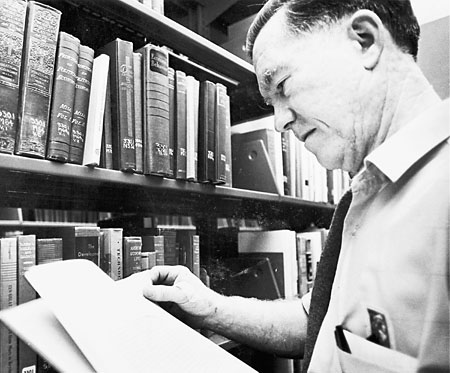

![James Stevens (1892-1972)]()

James Stevens (1892-1972)

James Stevens, whose national reputation was based on his popularizatio…

-

![Jean M. Auel (1936-)]()

Jean M. Auel (1936-)

No contemporary Oregon writer has achieved the superstar celebrity stat…

-

![Ken Kesey (1935-2001)]()

Ken Kesey (1935-2001)

A farm boy from the Willamette Valley, Ken Kesey brought an earthy, ind…

-

Kim Stafford (1949 - )

Kim Stafford, Oregon’s ninth Poet Laureate, is a poet, essayist, memoir…

-

Lawson Fusao Inada (1938-)

Poet, writer, and educator, Lawson Fusao Inada is an emeritus professor…

-

![Molly Gloss (1944-)]()

Molly Gloss (1944-)

Molly Gloss, prize-winning novelist and short-story writer, was born in…

-

![Nard Jones (1904-1972)]()

Nard Jones (1904-1972)

Nard Jones—novelist, historian, and journalist—wrote prolifically about…

-

![Opal Whiteley (1897-1992)]()

Opal Whiteley (1897-1992)

In March 1920, the Atlantic Monthly ran the first of six excerpts from …

-

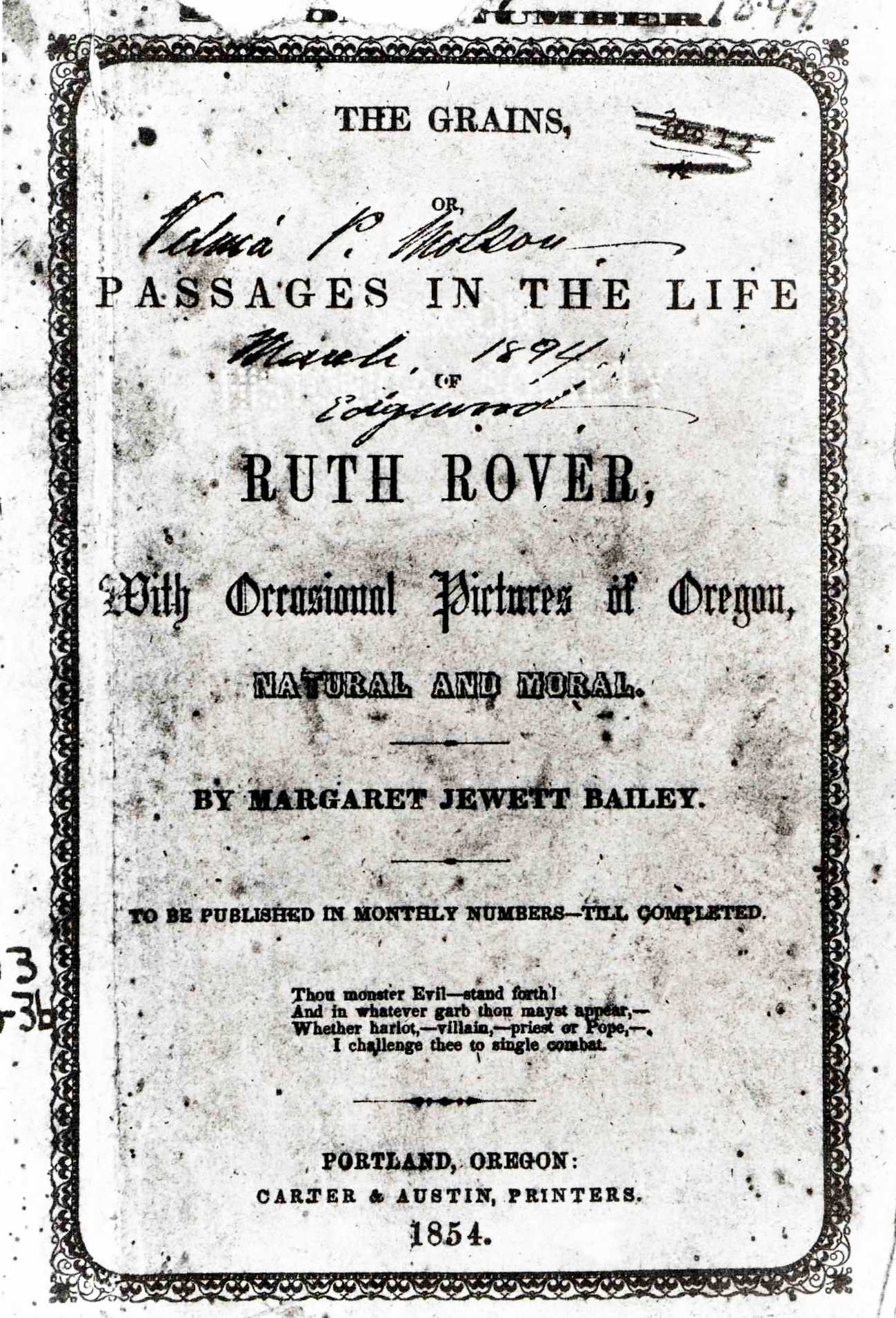

![Oregon Literature (1814-1920)]()

Oregon Literature (1814-1920)

The first literature of Oregon followed patterns typical of most other …

-

![Oregon Literature Series]()

Oregon Literature Series

“The Oregon Literature Series is a national model,” wrote John Frohnmay…

-

![Richard Brautigan (1935-1984)]()

Richard Brautigan (1935-1984)

Novelist and poet Richard Brautigan was raised largely in Eugene and at…

-

Ursula K. Le Guin (1929–2018)

Ursula K. Le Guin, one of Oregon’s preeminent writers, was born Ursula …

-

![William Kittredge (1932-2020)]()

William Kittredge (1932-2020)

William Kittredge is an award-winning author, influential teacher, and …

-

![William Stafford (1914-1993)]()

William Stafford (1914-1993)

William Stafford, one of America’s most widely read poets, was born in …

Related Historical Records

Further Reading

Bingham, Edwin R., and Glen A. Love, eds. Northwest Perspectives: Essays on the Culture of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1979.

Browne, Sheri Bartlett. Eva Emery Dye: Romance with the West. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2004.

Etulain, Richard W. Re-imagining the Modern American West: A Century of Fiction, History, and Art. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1996.

Findlay, John, et al. Reading the Region: History and Literature of the Pacific Northwest. Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle: University of Washington, n.d.

Gastil, Raymond D., and Barnett Singer. The Pacific Northwest: Growth of a Regional Identity. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2010.

Simonson, Harold P. "Pacific Northwest Literature—Its Coming of Age." Pacific Northwest Quarterly 71 (Oct. 1980), 146-151.

Venn, George, and Ulrich H. Hardt, eds. The Oregon Literature Series. 6 vols. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 1993.