A farm boy from the Willamette Valley, Ken Kesey brought an earthy, independent spirit to the American literary scene and to his self-designated role as the young Turk of the 1960s counterculture. His literary reputation rests on two novels, both written before he was thirty. His fame (or notoriety) as a countercultural icon stems from his band of willful misfits, the Merry Pranksters, who openly used and advocated psychedelic drugs. Kesey’s antics made him an object of admiration and scorn, yet his willingness to push limits and redefine normal boundaries came with a serious sense of purpose.

Kesey was born in La Junta, Colorado, on September 17, 1935. When he was eleven, his parents moved to the Springfield area to establish a dairy cooperative. In 1956, he married Faye Haxby. They had three children and raised a daughter from his liaison with fellow Merry Prankster Carolyn Adams.

Kesey’s pugnacious personality was shaped during his years at Springfield High School and the University of Oregon, where he was a champion wrestler and football player. After earning his bachelor’s degree in speech and communications in 1957, he entered Stanford University’s graduate writing program on a Woodrow Wilson scholarship. There, while under the guidance of writers Wallace Stegner and Malcolm Cowley, he forged his lifelong friendship with writer Ken Babbs and absorbed the influence of Beat writers such as Jack Kerouac.

In California, Kesey was exposed to the electronic backbeat of a new cultural consciousness as well as to some of its heroes, the most important of them Neal Cassady. Equally important was his job at the Menlo Park Veterans Hospital, where he took LSD and mescaline as a paid volunteer.

Kesey used his experiences at the hospital to launch his writing career with One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1962), which Time described as a protest novel that demonstrated Kesey’s “empathy for the Insider’s view of the Outsider’s world.” Much has been made of Kesey’s introduction to hallucinogenic drugs. Less discussed has been how the writer studied the thought processes of the real-life models for his characters and found his larger theme of how society and technology are used to repress the individual. Charges that the novel is anti-feminist stem from Kesey's depiction of the sadistic Big Nurse, although some critics counter that she is intended to be a distortion of womanhood, not its representative.

Kirk Douglas bought the stage rights to the novel and starred as the main character, Randle Patrick McMurphy, during a short run on Broadway. The movie version, with Jack Nicholson in the McMurphy role, was released in 1975. Kesey, hired and then fired as a screenwriter for the movie, sued for breach of contract and received an out-of-court settlement that eventually earned him over a million dollars in royalties.

To work on his second novel, Sometimes a Great Notion (1964), Kesey moved from his Northern California ranch to the coastal town of Florence, Oregon, to research Oregon’s logging country. In his notes for the novel, he summed up its direction: “A man learns too late in life what he has to offer and the right way to offer it.” Kesey was talking about Henry Stamper, the unyielding patriarch of his fictional lumber family, who would rather die fighting the speeding current than yield to it. The novel stands among the consummate works of fiction about the Pacific Northwest. Paul Newman’s production company released the movie version, starring Newman and Henry Fonda, in 1970.

To celebrate the publication of the novel, Kesey and the Merry Pranksters drove from Oregon to New York City in Further, a school bus adorned in Day-Glo paint. During the odyssey, they shot more than forty hours of film to create The Movie, which was later shown at events that were called Acid Tests. The trip marked a turning point for Kesey, who had made a conscious choice to “put on another costume”—that is, to step away from or, at least, beyond writing as an expression of his values and ideas.

Back in California, Kesey was arrested twice for marijuana possession and spent about five months serving his sentence. After his release in 1967, he made a deliberate retreat from California to a seventy-five-acre farm in Pleasant Hill (Lane County), his permanent home. From there he lent his support to the state’s nascent efforts to control growth with comprehensive land-use planning. He was still an iconoclast, but an older and wiser version of his Prankster self. He ignored appeals to attend Woodstock.

Kesey’s writing ebbed more than it flowed while he raised his children and worked the land. Still, he contributed to prestigious magazines, initiated book-length projects about the Prankster days, and founded a short-lived literary publication, Spit in the Ocean. He also wrote three plays and two children’s books and edited the 1971 supplement to The Whole Earth Catalogue.

In 1984, Kesey’s son, Jed, a member of the University of Oregon wrestling team, was killed when the van in which the team was traveling went off the road. Kesey faulted the school and the state for failing to equip the van adequately and donated a new vehicle to the team.

In 1987-1988, Kesey led a creative-writing class at the University of Oregon in which his students collaborated with him on a group novel, Caverns (1989), written under the pseudonym O.U. Levon. "One of the problems," he said later, "was that the students kept looking for the answers to symbolic riddles and believed that modern fiction is supposed to supply you with the answer. The answer is never the answer. What's really interesting is the mystery."

In 1992, Kesey published two lesser novels, Sailor Song and Last Go-Round: A Dime Western, a fictional replay of the 1911 Pendleton Round-Up co-written with Ken Babbs.

Kesey died in Eugene on November 10, 2001. He is memorialized there by a life-sized sculpture of him in his trademark touring cap reading to three children.

The Kesey family is restoring Further, perhaps the most famous school bus in history, with plans to use it as a traveling exhibit to museums. Kesey’s papers are currently housed at the University of Oregon.

-

![Ken Kesey, 1978]()

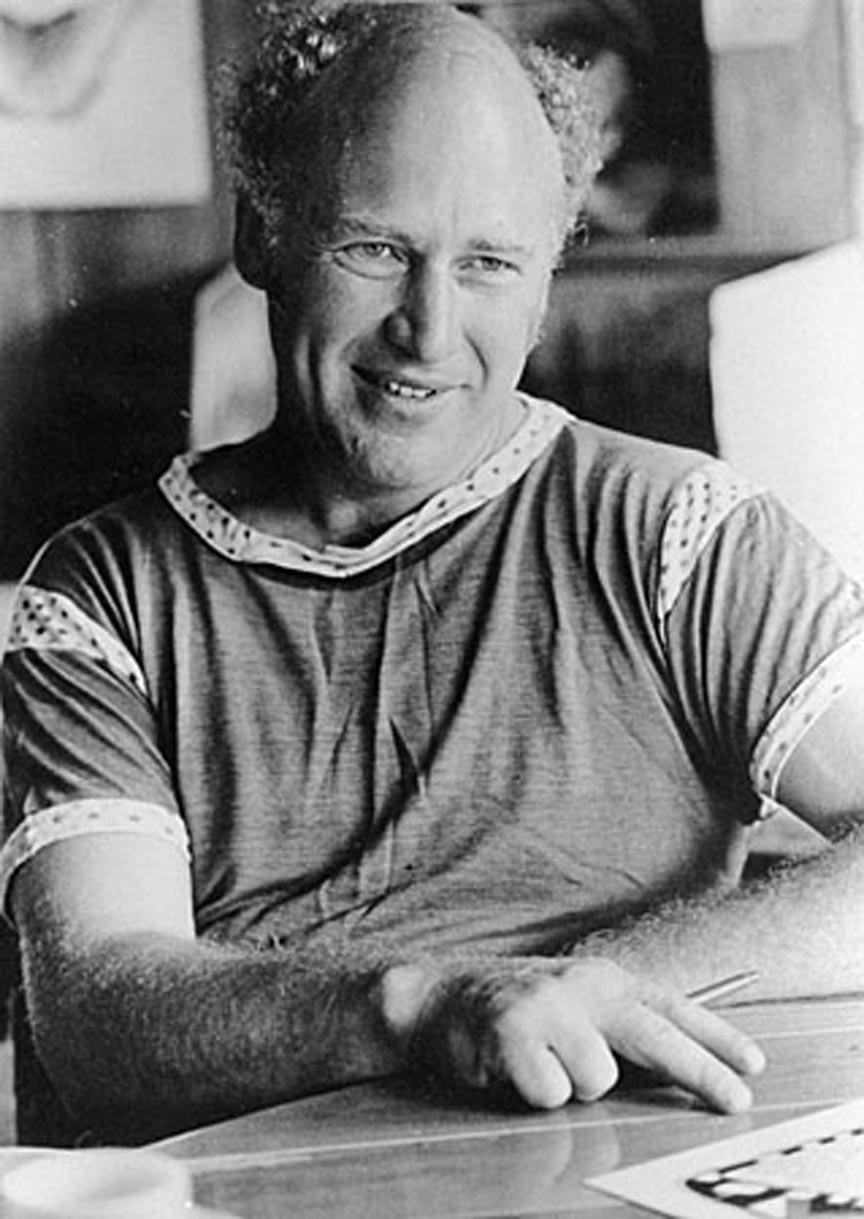

Ken Kesey, 1978.

Ken Kesey, 1978 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 105106

-

![]()

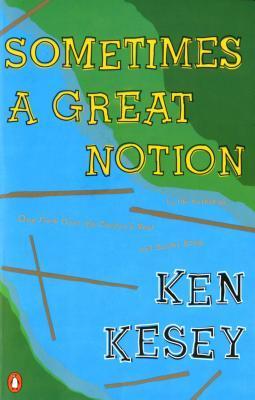

Kesey's "Sometimes a Great Notion," first published in 1964.

Penguin Books

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Bowman, David. “Still Crazy After All These Years.” Contemporary Literary Criticism, ed. Tom Burns and Jeffrey W. Hunter. Vol. 184. Detroit: Gale, 2004.

Tanner, Stephen L., and Laura M. Zaidman. The Concise Dictionary of American Literary Biography, Vol. 6: Broadening Views, 1968-1988. Detroit: Gale, 1989.