James Stevens, whose national reputation was based on his popularization of the legends of Paul Bunyan, was an early icon of Northwest literature. As Sinclair Lewis wrote, “No one knows the violent men, the violent mountains and woods, of the not-so-old west better than James Stevens, or can recall them more musically.”

In 1926, when Stevens and writer H.L. Davis published Status Rerum: A Manifesto, upon the Present Condition of Northwestern Literature, creative writing in the Pacific Northwest was mired in Victorian sentimentality. The co-authors not only deplored the state of northwestern literature in general terms, but also dissected each of the region’s literary luminaries, their journals, and their mentors. “The Northwest…has produced a vast quantity of bilge,” they concluded, “so vast, indeed, that the few books which are entitled to respect are totally lost in the general and seeming interminable avalanche of tripe.” They used terms and phrases such as “vile,” “contemptible,” “colossal imbecility,” and “a banquet of breath-tablets” to characterize the region’s literary landscape. In succeeding years, the literary work of Stevens and Davis would raise considerably the standards of Northwest literature.

James Stevens was born in 1892 on a rented farm in Iowa, raised first by his grandmother and then his relatives in Idaho. He left home at fifteen to work in logging camps, where he first heard stories of Paul Bunyan. Stevens fought in France during World War I and published his Paul Bunyan stories in Stars and Stripes. After the war, he became “a hobo laborer with a wistful literary yearning” and educated himself by reading omnivorously in public libraries.

In 1916, Stevens published his poetry in the Saturday Evening Post,and in the 1920s he began publishing in H.L. Mencken’s American Mercury, arguably the most influential magazine for thinking people at the time. Because of his association with that magazine, he met many of the literary luminaries of the day, including H.L. Davis.

One of Stevens’s Paul Bunyan stories in the American Mercury evolved into a full-length book, Paul Bunyan, which was published by Knopf in 1925. Stevens did not consider himself a folklorist but a literary artist who refined the ore he extracted from the mines of folklore. He would go on to publish more than 250 stories and magazine articles.

In 1936, in the middle of the Great Depression, Stevens returned to the Northwest and became the head of public relations for the West Coast Lumberman’s association, a position he held for twenty-five years. In 1948, he published his best-received novel, Big Jim Turner. Like all of his novels, Big Jim Turner had strong autobiographical elements and celebrated the workingmen and women of the Northwest. “Ranch hand, mule skinner, hard rock driller, logger, big town truck teamster, Wobbly, hobo poet,” he wrote, “I worked as my hero works…and dreamed as he dreams.” His prose style, influenced by Walt Whitman, Jack London, and Mark Twain, strove to elevate his western characters to Homeric heights.

Stephens died in Seattle on New Year's Eve in 1971 at the age of seventy-nine. He was survived by his widow, Theresa Seitz.

-

![Carl Sandberg with other Oregon writers, with James Stevens at far left, Corvallis, Feb. 1927.]()

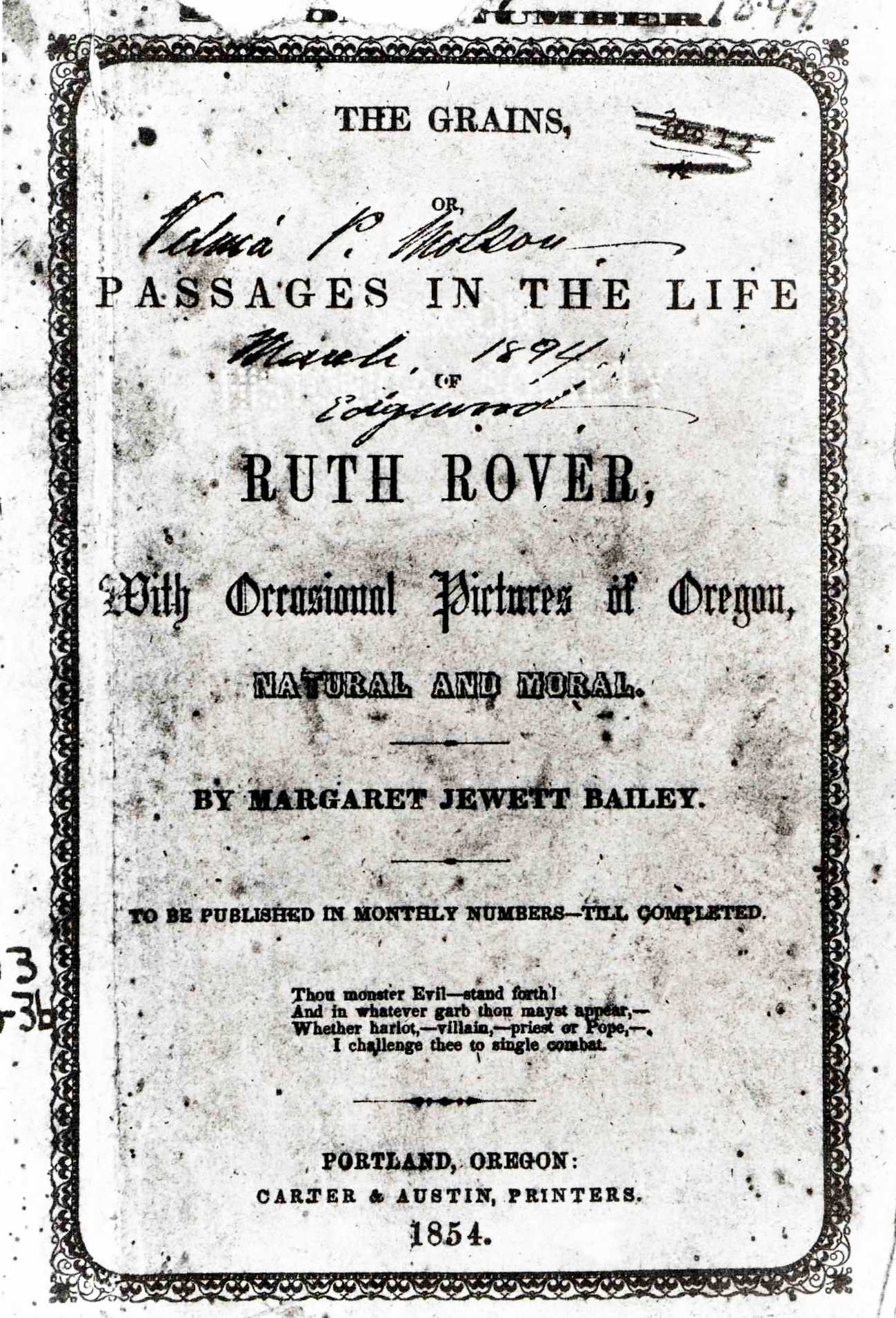

Sandberg, Carl, with OR writers, Feb 1927, bb007585.

Carl Sandberg with other Oregon writers, with James Stevens at far left, Corvallis, Feb. 1927. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb007585

Related Entries

-

![Harold Lenoir Davis (1894-1960)]()

Harold Lenoir Davis (1894-1960)

Born and raised in rural and small-town Oregon, Harold Lenoir Davis was…

-

![Oregon Literature (1814-1920)]()

Oregon Literature (1814-1920)

The first literature of Oregon followed patterns typical of most other …

-

![Oregon Literature (1920-2010)]()

Oregon Literature (1920-2010)

The joint appearance in 1927 of the controversial pamphlet Status Rerum…

-

![Stewart Holbrook (1893–1964)]()

Stewart Holbrook (1893–1964)

From Oregonian Stewart Holbrook's first book through his three dozen la…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Love, Glen A. “Stemming the Avalanche of Tripe.” In H. L. Davis, H. L. Davis: Collected Essays and Short Stories. Moscow, Id.: University of Idaho Press, 1986.

Maguire, James H. “James Stevens.” Boise State University Western Writers Series 165. Boise, Id.: Boise State University Press, 2005.