The world's first and most extensive system of protected rivers began with congressional passage of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act in 1968. The rivers of Oregon have taken a prominent place in the program ever since.

The idea of a nationally safeguarded system of rivers began with wildlife biologists John and Frank Craighead. Battling plans to dam Montana's Middle Fork Flathead, the twin brothers in 1958 realized that hundreds of massive dams had been proposed for rivers across America and that protecting them would mean an endless series of rearguard battles--unless Congress permanently set aside some of the finest natural streams to remain free flowing.

The idea fell into the receptive hands of several Department of the Interior officials, who in the 1960s took bold initiative to craft a national strategy and to survey the country for the most worthy streams. An initial list of 650 rivers was whittled to 74 for further study, including Oregon's lower Rogue and Deschutes.

With fortuitous synergy, President John F. Kennedy appointed Stewart Udall as secretary of the Interior in 1961. Udall personified the upheaval in water development philosophy of his time. As an Arizona congressman he had voted for dams that destroyed rivers, but with the help of river advocates he saw with increasing clarity the need for protection. By his own accounts, he was inspired by the heady alchemy that effervesces when a person clutches a paddle, steps into a canoe or raft, and kicks off from shore. His internal conflict sparked a new approach: to balance the ubiquitous dam-building of his era with conservation of the finest remaining rivers.

Interior Department staff worked with key members of Congress, including Senator Frank Church (D-ID), Senator Gaylord Nelson (D-WI), and Representative John Saylor (R-PA), to draft the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. With encouragement from Rogue River outfitters and guides who were concerned about the proposed Copper Canyon Dam on the lower river, Oregon Senator Mark Hatfield (R) also supported the effort.

The Senate voted unanimously for the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, while the House voted in favor 265-7; President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the bill into law on October 2, 1968. The act specified that rivers with "outstandingly remarkable" qualities for "scenic, recreational, geologic, fish and wildlife, historic, cultural, or other similar values shall be preserved in free-flowing condition." Such rivers can be of any size, and new designations are to be enacted by Congress or the Secretary of the Interior if a governor asks for it. Eight major rivers, plus four of their tributaries, were designated in 1968, and Oregon's lower Rogue River was a key member of this prestigious group. Protocols were established with the intent to add rivers in the future.

Foremost, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act bans dams and other federal developments that would damage the specified streams. When federal permits are required for developments by other entities, the act also bars approval of damaging projects such as private hydroelectric dams. Rivers are classified as wild, scenic, or recreational depending on the extent of houses, roads, or facilities already there. Regulation of private land use is not allowed, but the act encourages local governments to zone private acreage for purposes such as floodplain management. Designation does not prescribe the acquisition of open spaces but can encourage it through management plans.

In 1970, a separate citizen initiative in Oregon won by a 2-1 margin to launch the state's Scenic Waterways Program. Similar in some respects to the national system, the state program in 2018 included 22 rivers and streams totaling 1,200 miles. State protection is not as effective as the federal law is in banning dams or private hydroelectric projects, which are licensed by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission without requirements for state concurrence. Nor does state designation commit the federal government to increased management efforts for protecting river qualities.

The Snake River

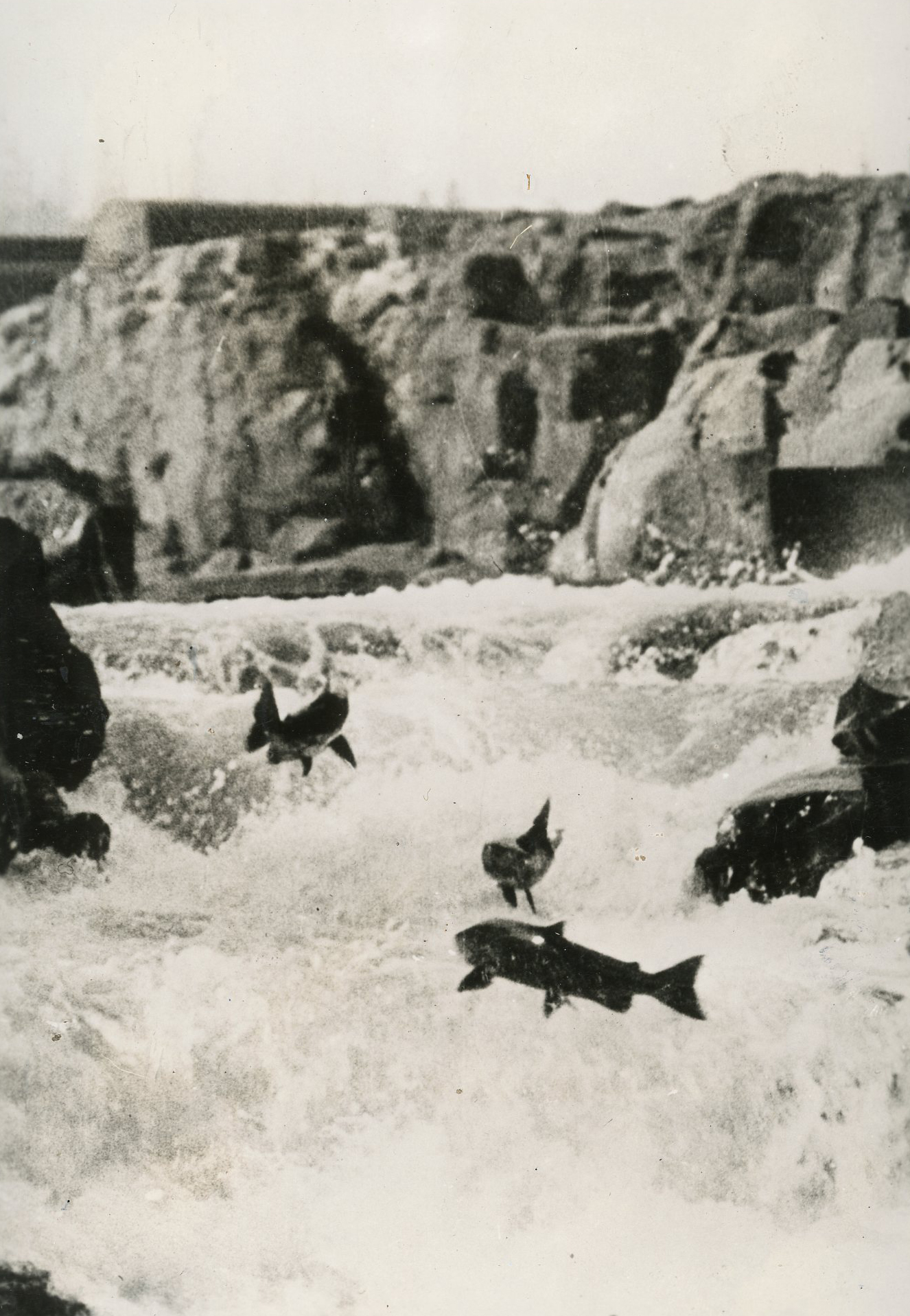

Soon after the national program was enacted, the Snake River at the border of Oregon and Idaho became a test case for the intent and effectiveness of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. A dam proposed in the heart of Hells Canyon would have flooded much of the remaining free-flowing mileage of one of America's deepest canyons and eliminated native Chinook salmon that spawned in the main channel of the river. The project was stalled when a young environmental lawyer, Brock Evans, filed a last-minute appeal to the Federal Power Commission in Seattle.

Resulting delays allowed time for a multiyear conservation campaign, and monolithic support for the dam was broken when Oregon Senators Bob Packwood and Mark Hatfield opposed it and Idaho Governor Cecil Andrus declared the dam would be built only "over my dead body." Wild and Scenic designation on the Snake through Hells Canyon in 1975 secured the largest whitewater in the West next to the Grand Canyon and reaffirmed the power of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act in protecting streams from imminent dam threats. The Rogue's largest tributary—the Illinois River—was added to the national system in 1984, barring further planning for a hydroelectric dam once proposed by the Coos-Curry Electric Cooperative near its mouth.

Advocating for Oregon

One of the greatest leaps forward for the program came with the Omnibus Oregon Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1988. The Oregon Rivers Council (now Pacific Rivers) in the mid-1980s had crafted a proposal largely based on analysis of Wild and Scenic eligibility of rivers flowing mostly through public land. Senator Hatfield pushed the bill through, designating 53 major streams—44 rivers plus 9 tributaries—mostly in national forests. This remains the largest number of rivers inducted into the national program at any one time. Included were portions of many of Oregon's free-flowing gems, including the upper Rogue, North Umpqua, McKenzie, Clackamas, Deschutes, Metolius, John Day North Fork, and Grande Ronde. The so-called Oregon strategy of designating a sizable package of rivers flowing mostly through federal land and already considered eligible for Wild and Scenic status by the federal managing agency was repeated, though with substantially smaller bills, in Michigan and Arkansas in 1992.

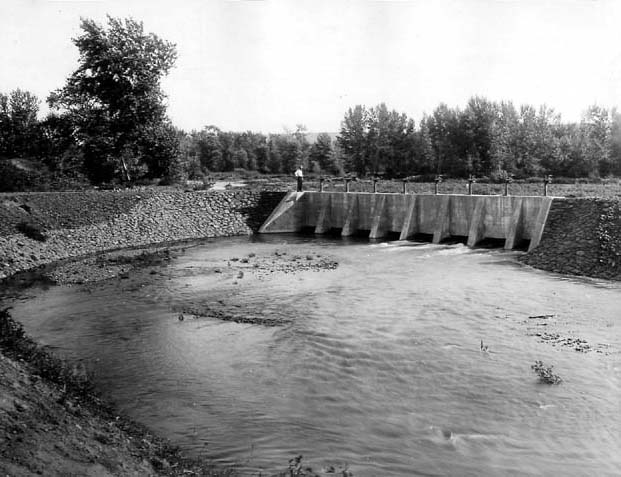

In the 1980s and 1990s, the City of Klamath Falls proposed a hydroelectric project on Oregon's section of the Klamath River that would sharply deplete the river's flows, decimating fish populations there and eliminating one of the Northwest's premier runs of big-volume whitewater. The National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act allows for an alternate method of designation—if a state has taken its own protective measures, then the governor can request national designation by the U.S. Secretary of the Interior without a congressional vote. Governor Barbara Roberts and Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt took this bold step, designating 11 miles in 1994 and sparing Oregon's only river south of the Columbia that completely transects the Cascade Mountain range. (The John C. Boyle Dam had already been built on the upper Klamath in 1956-1958.)

Another major advance came in 2008 as efforts by local and statewide groups in Oregon, Idaho, Wyoming, and California were collected into a campaign orchestrated by American Rivers to designate forty more streams for the fortieth anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Act. Enacted early the next year—after Barack Obama was inaugurated as president—the Omnibus Public Land Management Act included several streams in the Mount Hood area and the two forks of the Elk River on the south coast.

Once waterways are designated as wild and scenic, the management of streams after their enrollment is critically important for protecting "outstandingly remarkable" values as mandated by the law. Administration and management are assigned to one of four federal agencies—the U.S. Forest Service, the National Park Service, the Bureau of Land Management, or the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service—or to the state. Some rivers—and the lower Rogue is an often-cited case—exemplify successes in management of access areas, permits to prevent overcrowding, and maintenance of recreation sites. Other rivers languish when management plans are not updated or implemented in the face of environmental threats. Some agency personnel lack adequate training about the program, and dedicated staff are swamped with competing duties (from campground maintenance to fire suppression) as budgets shrink. Small streams, such as Oregon's Elk River, have virtually no Wild and Scenic maintenance program on the ground, and others, such as Idaho's Lochsa River, have been embroiled in controversy about the mandates of managing agencies.

By 2014, the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System had grown to 208 major rivers. Many involve multiple forks or branches, and nearly 300 major rivers and tributaries are included. Counting minor streams, 495 named rivers and tributaries accounted for about 13,000 miles nationwide in 2018. Seventy percent of the designated rivers are in Oregon, California, and Alaska. With 59 rivers in the system, Oregon has the most, and Alaska has the greatest mileage at 3,210.

The greatest geographic concentration of protected rivers flow in coastal Oregon and northern California, where the basins of back-to-back designated streams extend from the Elk, Rogue, Chetco, and North Fork Smith in Oregon through the Eel in California—all spanning 260 miles north to south. By volume of flow, the Snake at the Oregon-Idaho state line is the largest river in the national program. The Klamath—including Oregon headwaters of the upper river and the tributaries Sycan and North Fork Sprague—has the most designated mileage, counting the main stem and tributaries. The Deschutes ranks eighth in that category for mileage within a single river's watershed.

Expanding protections

Though the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act was largely inspired by the need to safeguard rivers for recreation, advocates have addressed other provisions of the law. Protecting native fish habitats was part of the wild and scenic designation of the Smith River in California in 1981, as well as to the designations of a suite of Oregon rivers in 1988 and the Snake River headwaters in 2009. Ecosystem protection was listed as a goal for the Skagit River (Washington) designation, and community, cultural, and historical values underpinned the inclusion of other rivers added to the system, including prehistoric sites on streams such as Oregon's Owyhee with its petroglyphs.

The variable winds of politics have affected the growth of the Wild and Scenic Rivers system, especially with party-line polarization after 1994. What began with bipartisan support became largely dependent on Democratic congresses and presidents, with the exception of Ronald Reagan, whose hand was forced by a Democratic Congress.

Reflecting on the success of the national program, John Craighead in 1983 said, "I never expected it to grow so much." Stewart Udall said that he was "very pleased" with the results, though he added that the system was "incomplete" when compared to America's National Parks and designated wilderness areas.

Considering the most explicit and motivating goal of the original legislation—to stop unnecessary and damaging dams—the program has been successful. Impending dams were halted on several rivers, including the Snake, Rogue, Illinois, and Klamath in Oregon, and no section of river has been deleted to allow for a dam (though California's Merced was threatened in 2016 and later). Additional goals of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act have been met by improving recreation management, limiting clearcut logging in federal wild river corridors, and aiding municipalities with zoning, setbacks, and access.

It is a strong record, yet advocates such as American Rivers point out that the Wild and Scenic River system includes only 0.4 percent of the 2.9 million miles of rivers and perennial streams in the United States. At the same time, 80,000 sizable dams have been built on nearly every major stream outside Alaska, and one-third the total river mileage is significantly polluted. Most of the rest of those reaches that are not dammed have been channelized, diverted, or developed for floodplain management. Only about 3 percent of the nation's stream mileage was foundto retain qualities necessary for Wild and Scenic status, according to a Nationwide Rivers Inventory conducted by the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation and the National Park Service in 1994.

Only 24 of 74 classic rivers identified by Interior Department planners in their original survey for the national program have been designated since 1964, and growth of the system has slowed. In 2018, the system included 27 reaches longer than 100 miles—each one designated as wild and scenic before 1989, during the first half of the program's history.

Oregon is well represented in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers program. River protection initiatives in the state have succeeded relative to other states, largely because public agencies have created model management programs on key rivers such as the Rogue and North Umpqua. Propelled by efforts to protect and restore anadromous fisheries, including salmon and steelhead—by river runners who adopt favorite streams for stewardship and by Oregonians who recognize the value of free-flowing waterways—the program is likely to remain a critical part of river management, conservation, and use in Oregon and, in fact, to grow as new proposals for designation are advanced.

-

![]()

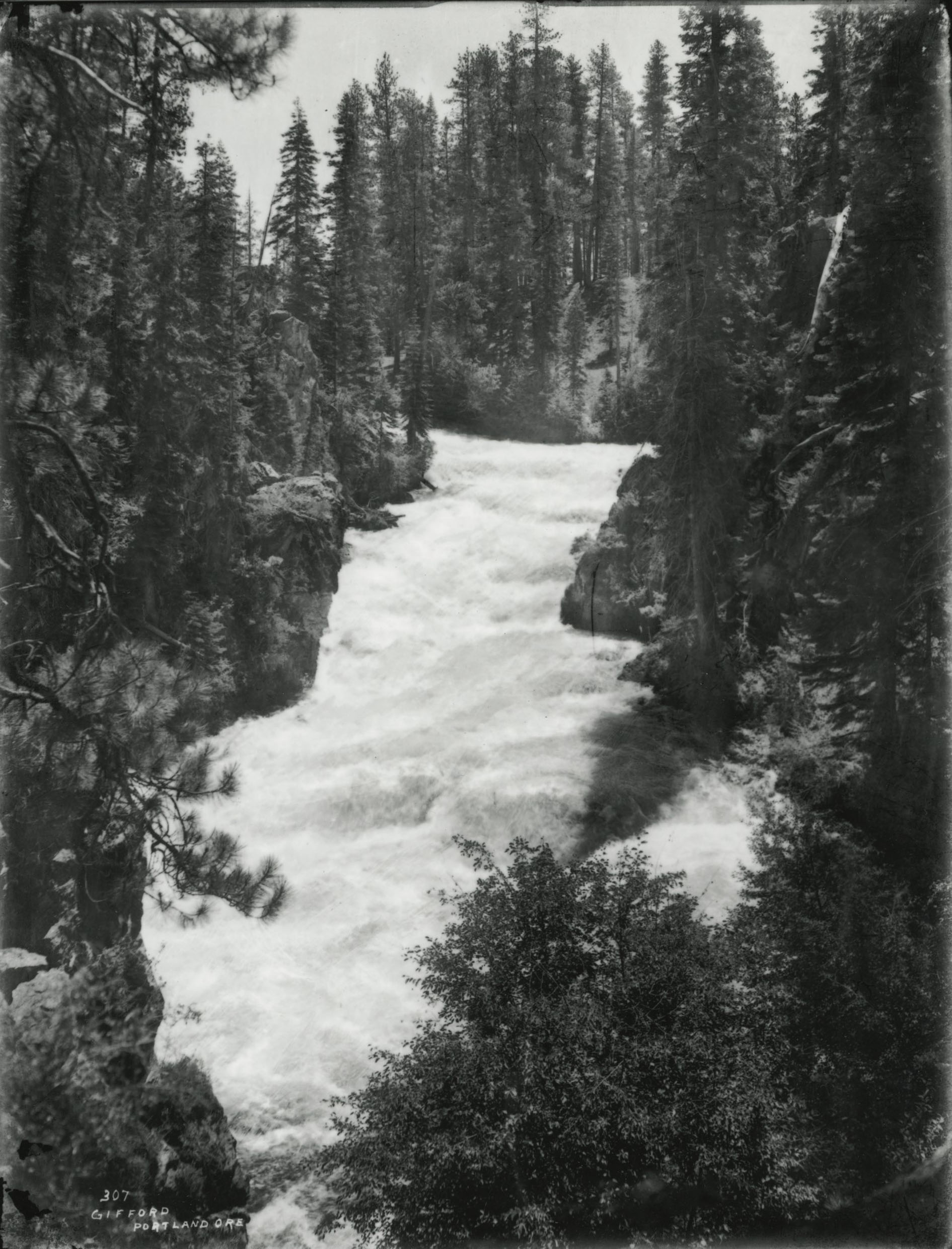

Benham Rapids, Deschutes River.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Benjamin Gifford, Org. Lot. 982, Box 3, folder 10, Gi307

-

![]()

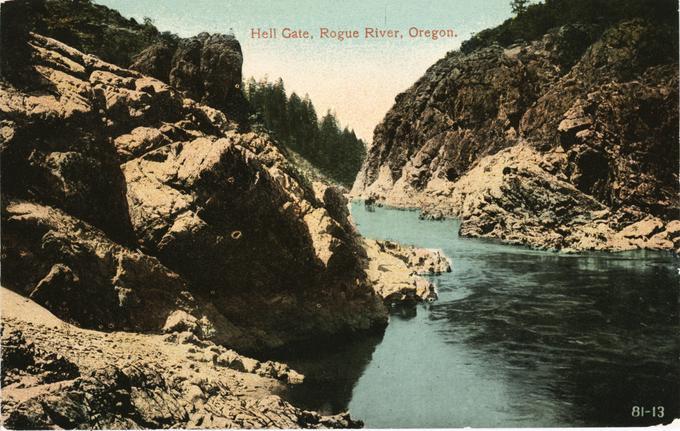

Hell Gate, Rogue River.

Courtesy Oregon State University Special Collections and Archives Research Center, Cronk Coll.

-

![]()

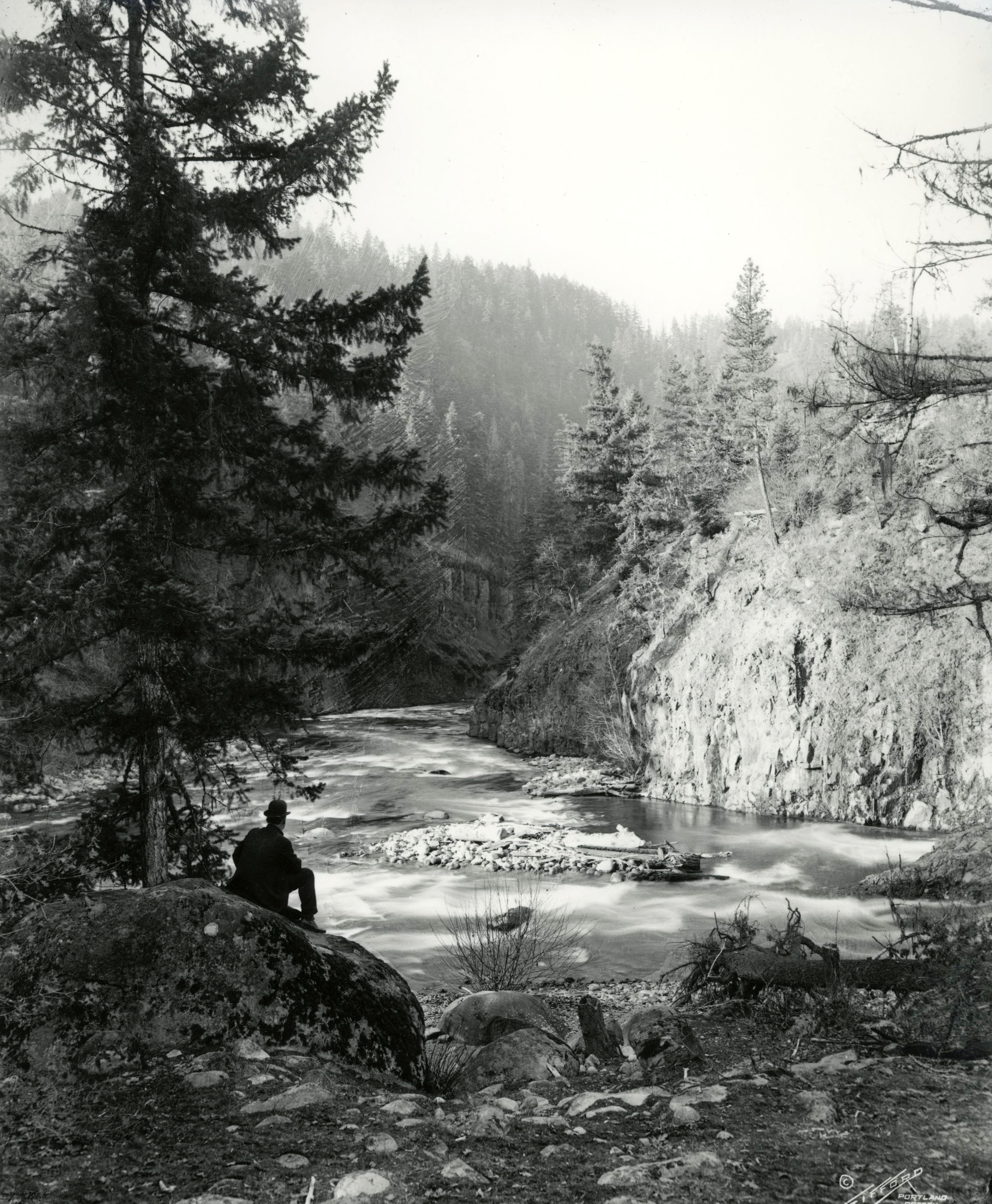

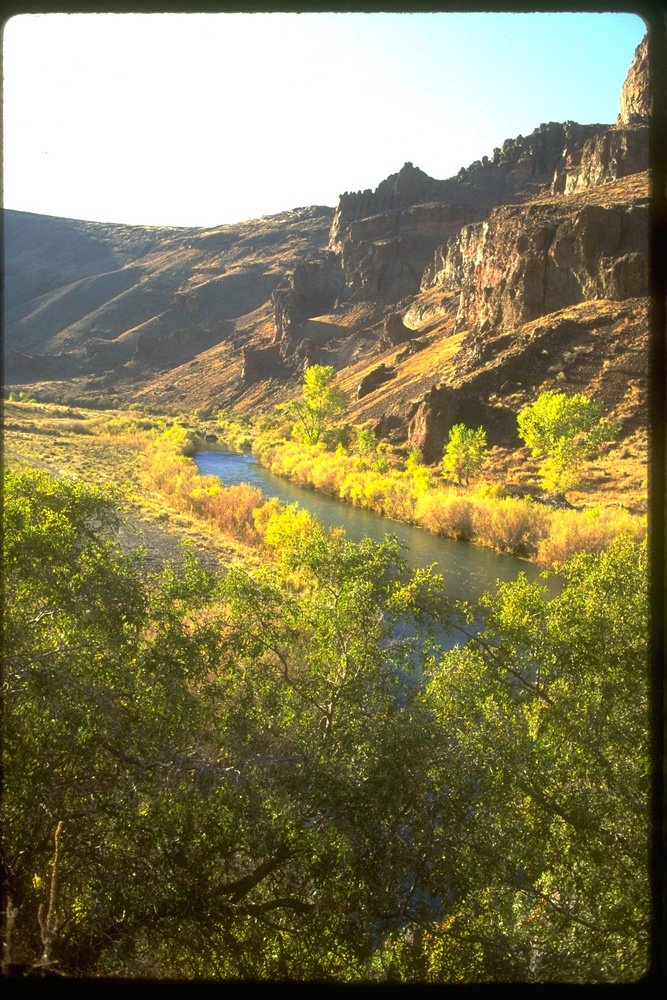

Donner und Blitzen River.

Courtesy Bureau of Land Management Oregon and Washington -

![]()

Rogue River.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Benjamin Gifford, Org. Lot. 982, Box 3, folder 21, Gi1926

-

![]()

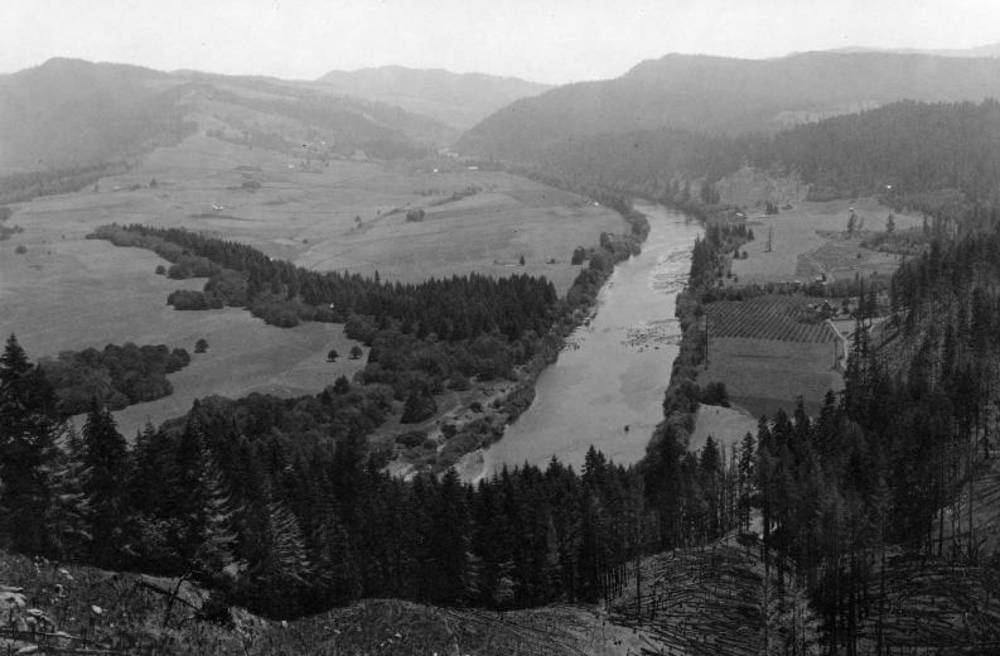

Umpqua River, North Fork.

Courtesy Bureau of Land Management Oregon and Washington -

![]()

Cline Falls, Deschutes River.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Benjamin Gifford, Org. Lot. 982, Box 3, folder 12, Gi643

-

![]()

Wooden boats along the Deschutes River, 1938.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Oregon Journal, Orhi102425, photo file 905D

-

![]()

Deschutes River vista.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Benjamin Gifford, Org. Lot. 982, Box 3, folder 13, Gi2394

-

![]()

The mailboat "Idaho Queen" on the Snake River, 1961.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Robert Hacker, Orhi1328, photo file 905S1

-

![]()

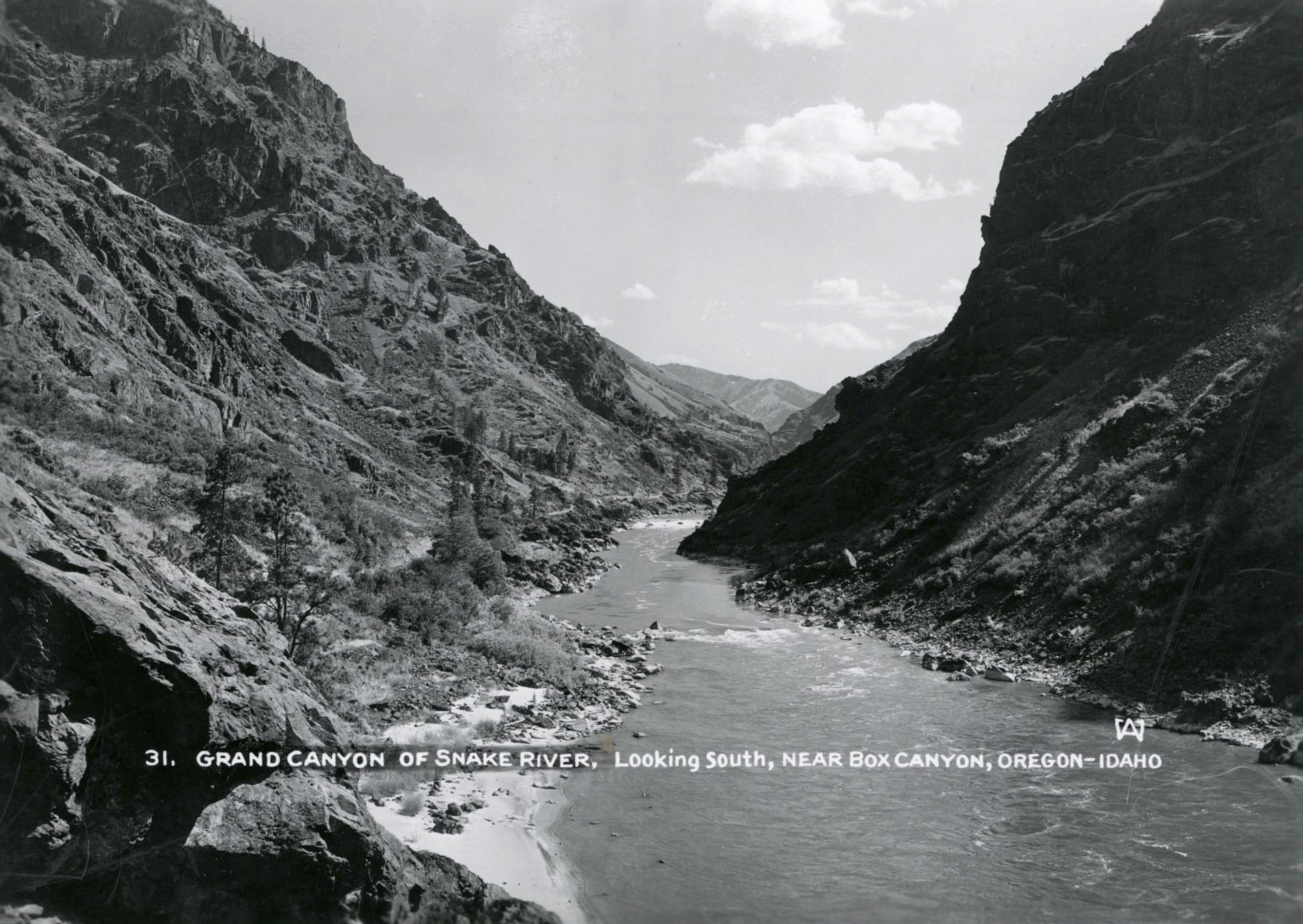

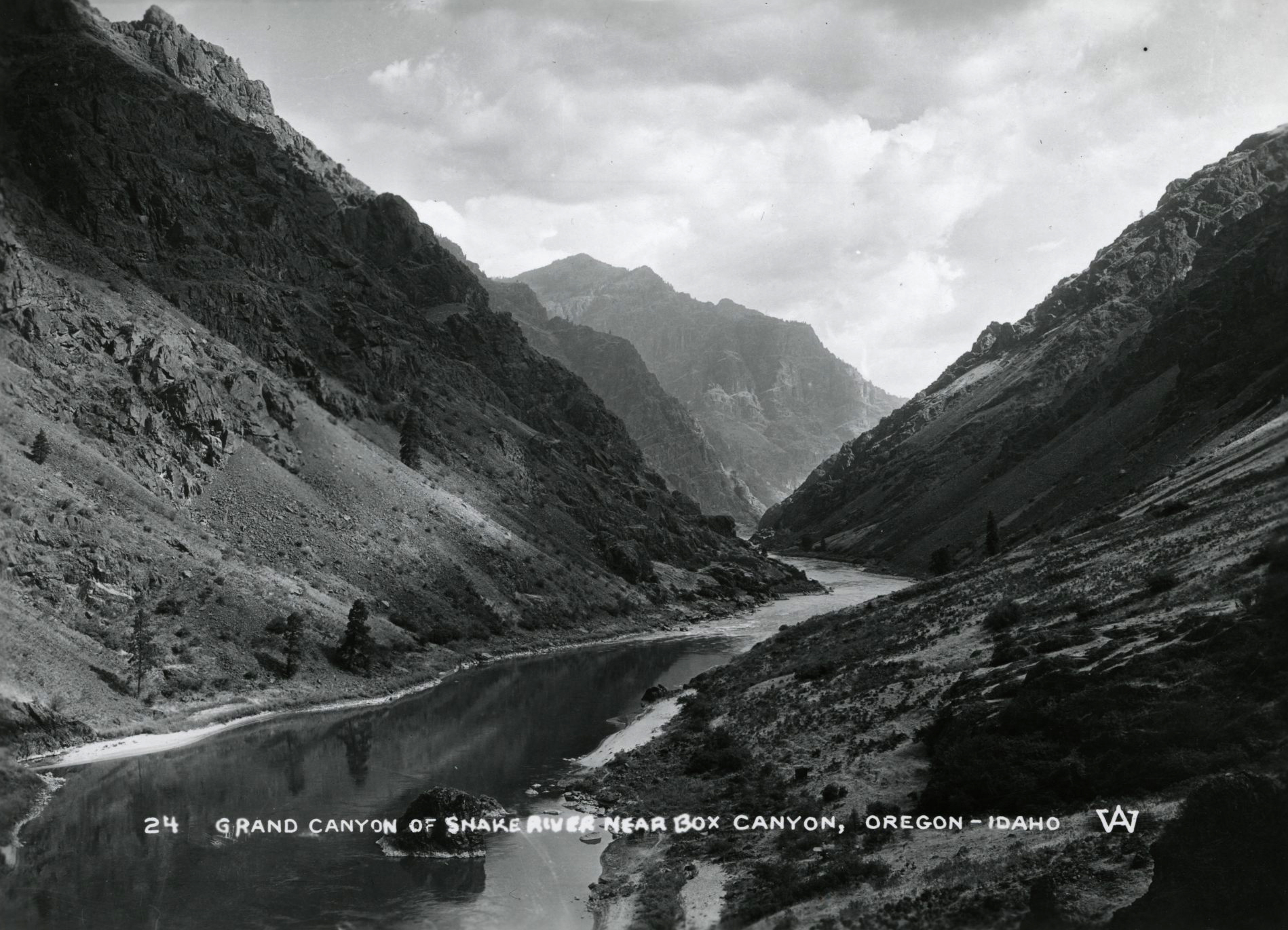

The "Grand Canyon" of the Snake River.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Wesley Andrews, 34783, photo file 905S1

-

![]()

Looking down the Snake River.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., B.C. Towne, 73273, photo file 905S1

-

![]()

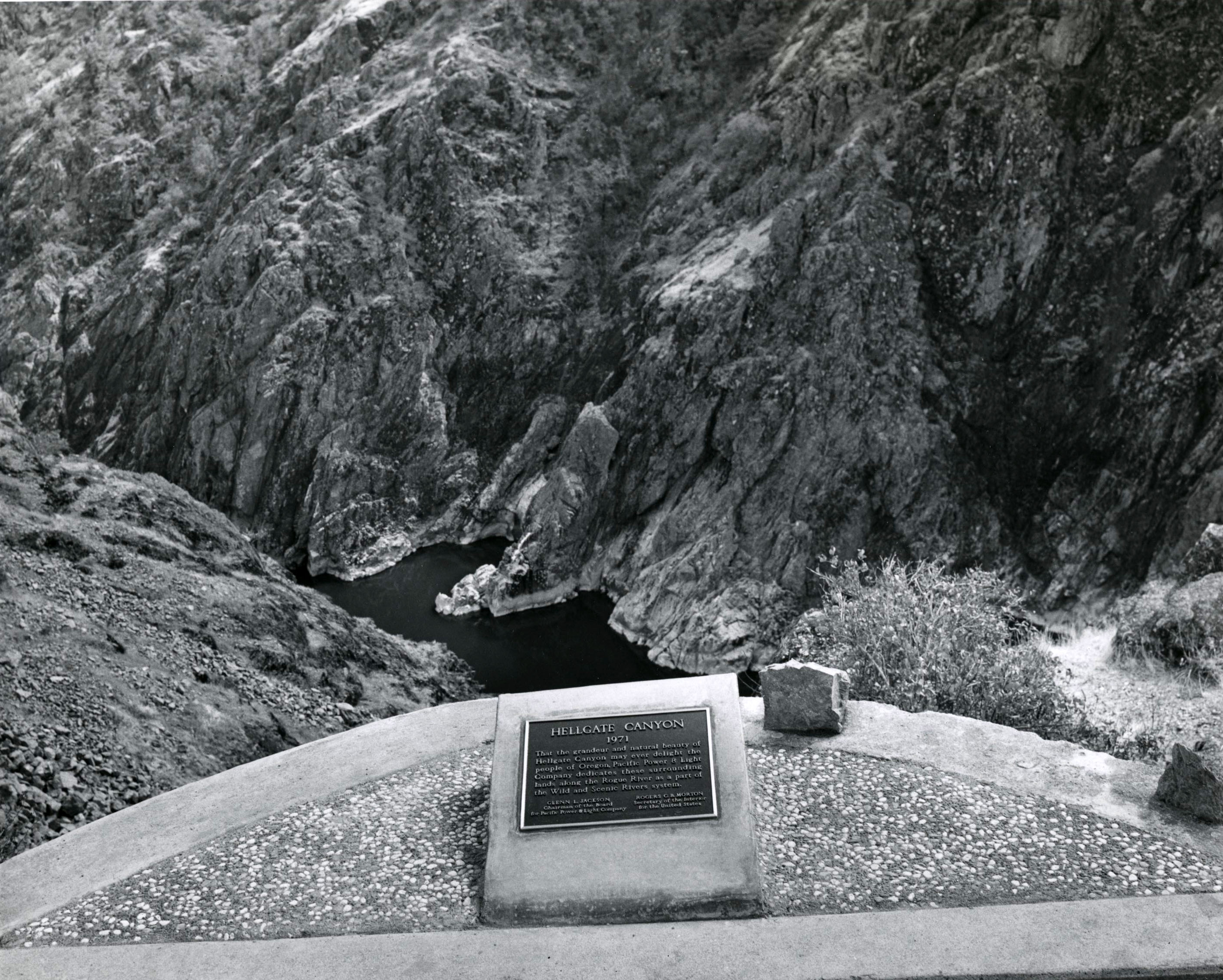

Hellgate memorial, when Portland, Power, and Light Co. donated land to Bureau of Land Management, 1971.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org. Lot 353, Box 2, folder 5, 30321

-

![]()

Tom McCall addresses a group at the Hellgate memorial, 1971.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org. Lot 353, box 2, folder 5, 3034

-

![]()

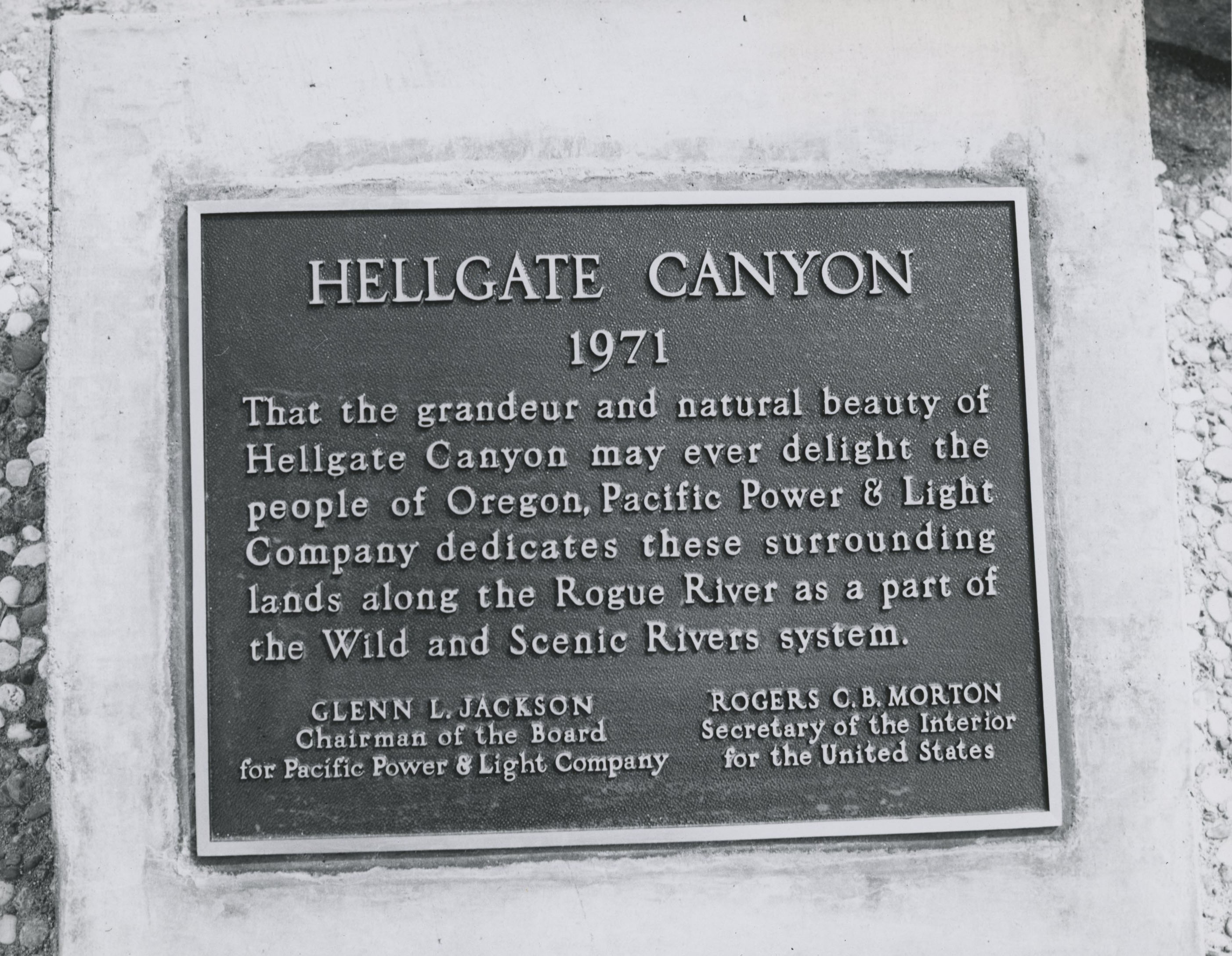

Bronze plaque at Hellgate, 1971.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Robert Hostetter, Org. Lot 353, box 2, folder 5, 30372

-

![]()

Grande Ronde River.

Courtesy Bureau of Land Management Oregon and Washington -

![]()

John Day River, South Fork.

Courtesy Bureau of Land Management Oregon and Washington -

![]()

McKenzie River.

Courtesy Bureau of Land Management Oregon and Washington -

![]()

Quartzville Creek.

Courtesy Bureau of Land Management Oregon and Washington -

![]()

-

![]()

Clackamas River, South Fork.

Courtesy Bureau of Land Management Oregon and Washington -

![]()

Birch Creek Historic Ranch, Owyhee River.

Courtesy Bureau of Land Management Oregon and Washington -

![]()

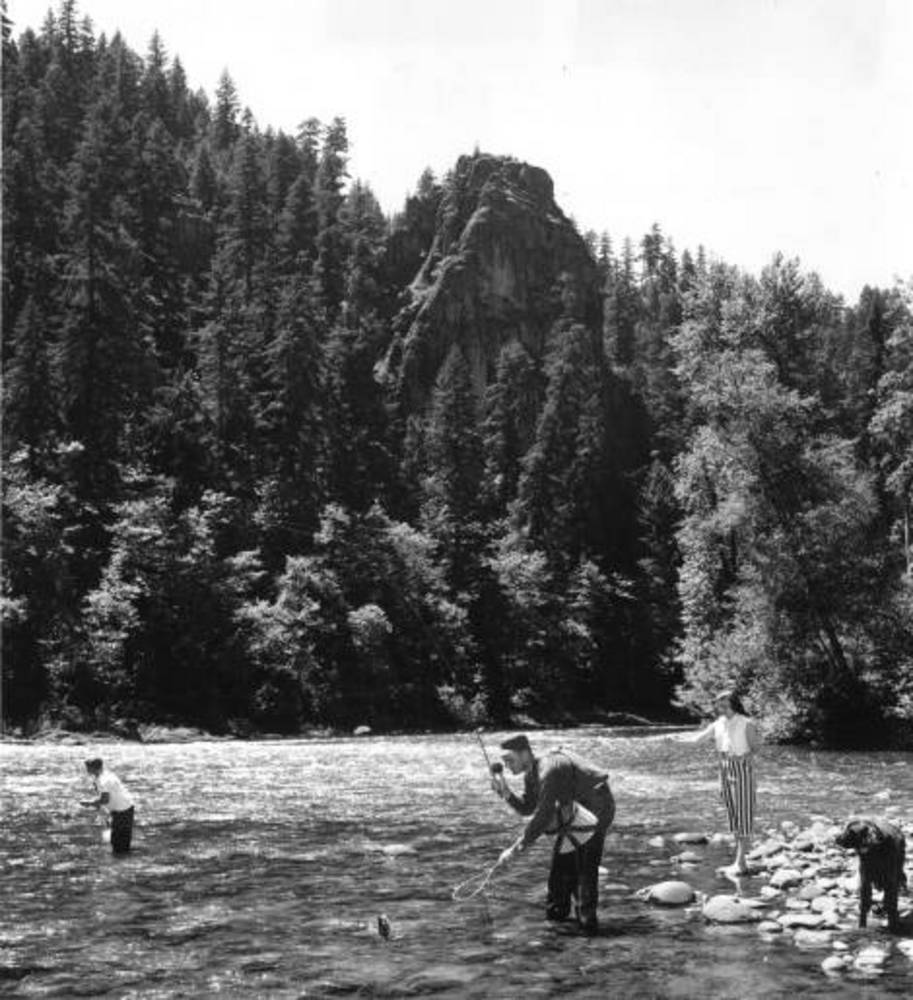

Fishing along the Klamath River.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., W.W. Hough, Orhi98522, photo file 905K

-

![]()

Cline Falls, Deschutes River.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Benjamin Gifford, Org. Lot. 982, Box 3, folder 12, Gi643

Related Entries

-

![Crooked River]()

Crooked River

The Crooked River Basin lies in the heart of central Oregon, east of th…

-

![Donner und Blitzen River]()

Donner und Blitzen River

From its headwaters on Steens Mountain, the Donner und Blitzen River wi…

-

![John Day River (north-central Oregon)]()

John Day River (north-central Oregon)

The 281-mile-long John Day River in north-central Oregon is the longest…

-

![Klamath River]()

Klamath River

The Klamath River originates on a plateau east of the Cascade Range in …

-

![McKenzie River]()

McKenzie River

The McKenzie River, on the western slope of the Cascade Range, starts o…

-

![Metolius River]()

Metolius River

The Metolius River is a spring-dominated tributary of the Deschutes Riv…

-

![Minam River]()

Minam River

The Minam River Basin on the west side of the Wallowa Mountains is one …

-

![North Fork John Day River]()

North Fork John Day River

Flowing 113 miles westward from the Blue Mountains, the North Fork John…

-

![Owyhee River]()

Owyhee River

The Owyhee River, in the southeastern corner of Oregon, is a 280-mile-l…

-

![Rogue River]()

Rogue River

The Rogue River, Oregon’s third-longest river (after the Columbia and W…

-

![Salmon]()

Salmon

The word “salmon” originally referred to Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar),…

-

![Sandy River]()

Sandy River

In 1805, William Clark called the 55-mile-long Sandy River the “quick S…

-

![Snake River]()

Snake River

The Snake River has its headwaters at an elevation of 8,200 feet on the…

-

![South Fork John Day River]()

South Fork John Day River

From its headwaters in the fir and ponderosa pine forests of Grant and …

-

![Tualatin Riverkeepers]()

Tualatin Riverkeepers

Tualatin Riverkeepers, a community-based organization that works to pro…

-

![Umatilla River]()

Umatilla River

The Umatilla River flows out of the forested northwestern slopes of the…

-

![Umpqua River]()

Umpqua River

The Umpqua River, approximately 111 miles long, is a principal river of…

-

![U.S. Bureau of Land Management]()

U.S. Bureau of Land Management

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) administers over 15.7 million acres…

-

![Wenaha River]()

Wenaha River

The Wenaha (weh-NAH-ha) River, arguably eastern Oregon’s most pristine …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Palmer, Tim. Rivers of Oregon. Eugene: University of Oregon Press, 2016.

---. Endangered Rivers and the Conservation Movement. Oakland: University of California Press, 1986.

---. The Snake River: Window to the West. Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 1991.

---. Wild and Scenic Rivers: An American Legacy. Eugene: University of Oregon Press, 2017.

Craighead, John. "Wild River." Montana Wildlife (June 1957): 16.

U.S. Department of the Interior and Department of Agriculture. Wild Rivers. Booklet. May 1965.

U.S. Department of the Interior and Department of Agriculture. "National Wild and Scenic Rivers System: Final Revised Guidelines for Eligibility, Classification and Management of River Areas." Federal Register, Sept. 7, 1982. p 39454-39459.

Thomas, Cassie, and Jackie Diedrich. Evolution of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act: A History of Substantive Amendments, 1968-2013. Wild and Scenic Rivers Coordinating Council report. https://www.rivers.gov/documents/wsr-act-evolution.pdf

Friends of the River "Merced Threat." 2016.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2004. National Water Quality Inventory.

U.S. Department of the Interior. "The Nationwide Rivers Inventory." White paper. January 1982.