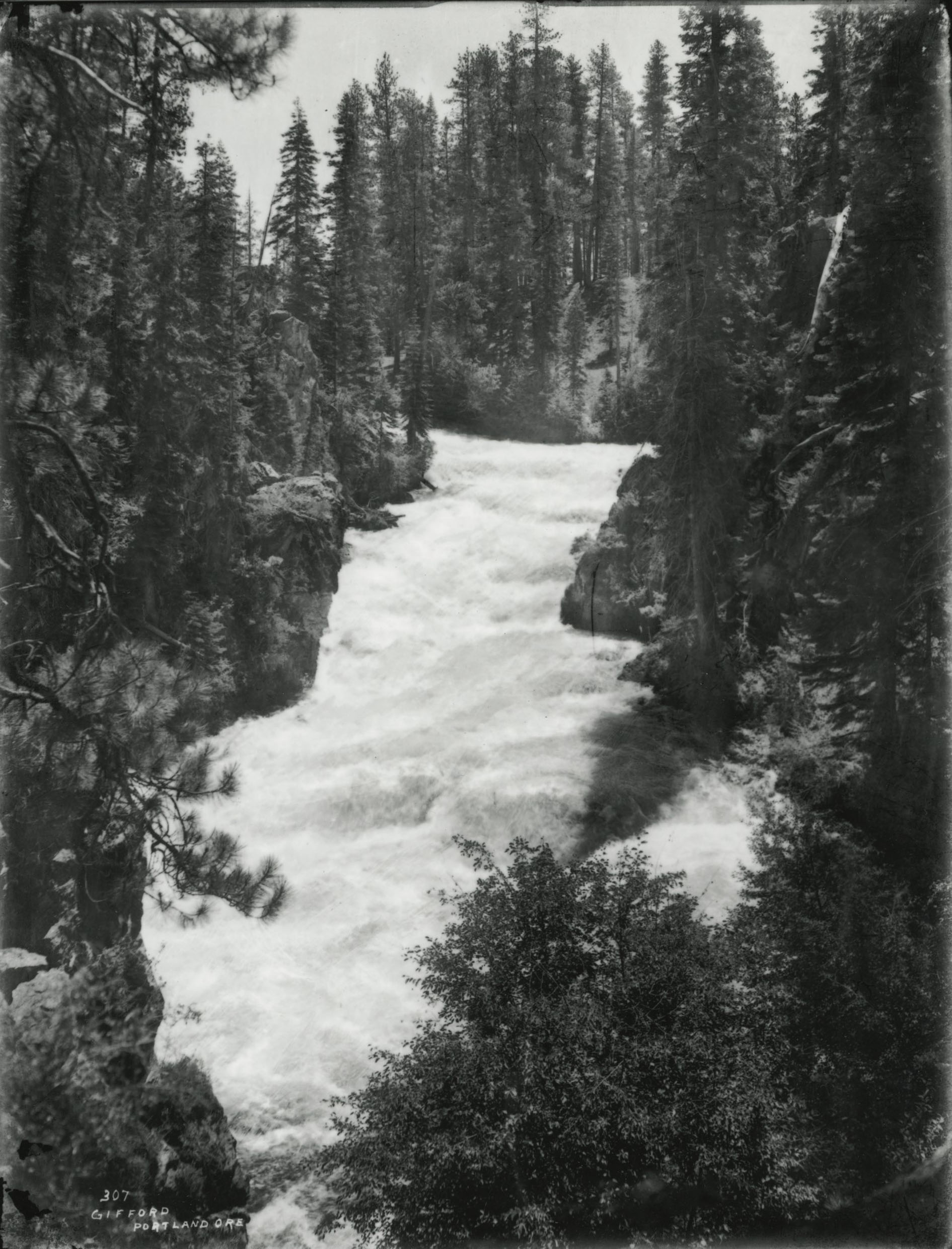

The Wenaha (weh-NAH-ha) River, arguably eastern Oregon’s most pristine forested waterway, gives its name to the 176,557-acre Wenaha–Tucannon Wilderness Area in the northern Blue Mountains. Almost the entirety of the main stem of the river, 21.8 miles, is included in the National Wild and Scenic River System. The Wenaha and its North Fork have a combined river length of 38 miles. Except for some flats on the southeast upper side of the river, the drainage has never been logged.

The Wenaha runs through ponderosa pine, Douglas-fir, grand fir, subalpine fir, western larch, and Engelmann spruce forests, with beautiful meadowed flats and ridges incised by 2,000-foot-deep valleys. The river basin is roadless except at the town of Troy, where the Wenaha empties into the Grande Ronde River at an elevation of 1,600 feet. The highest point in the drainage is the summit of Oregon Butte, at 6,387 feet, 7.6 miles north of the Oregon-Washington state line.

The longest Oregon tributaries of the Wenaha are Milk and Elk Creeks, but the headwaters of most of the river’s tributaries—Beaver, Slick Ear, Rock, Butte, Fairview, and Crooked Creeks—are on the Washington side of the wilderness area. The basin is 296 square miles in area—137 square miles of it in Oregon—and has a water discharge averaging 390 cubic feet per second. The Wenaha is subject to fire, and much of the eastern half of the drainage burned in the 2015 Grizzly Bear Complex fire.

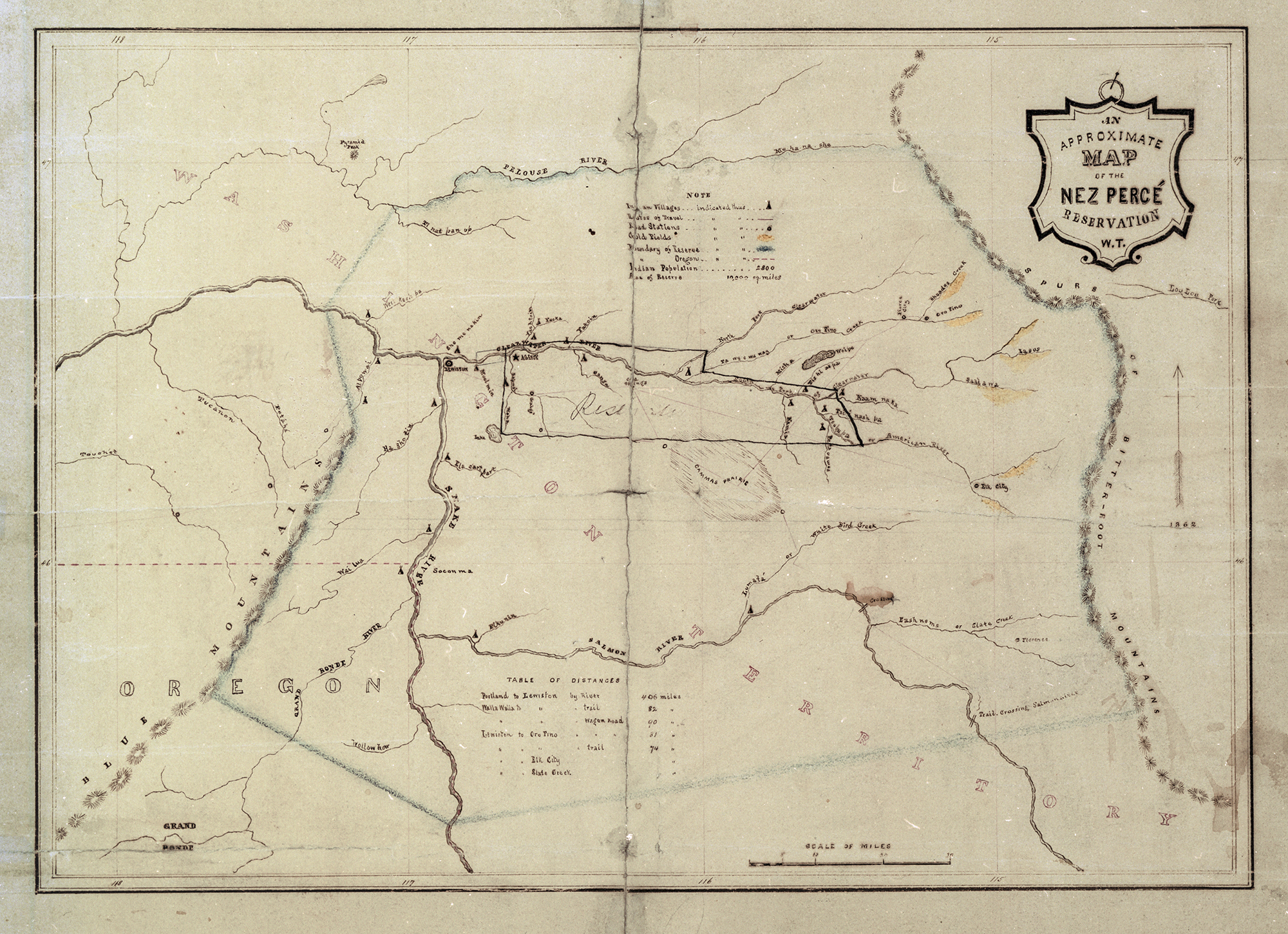

The name Wenaha (also spelled Wináha) honors the Nimiipuu (Nez Perce) band known as Wenak; ha refers to the land or realm governed by a Wenak subchief. On William Clark’s 1810 Map of the American West, the cartography incorrectly identifies the Wenaha as the principal source of the Grande Ronde. Clark referred to the entire drainage area as the Wil-le-wah, and he put the Native population at 1,000. Most of the Grande Ronde flow originates farther south along its drainage.

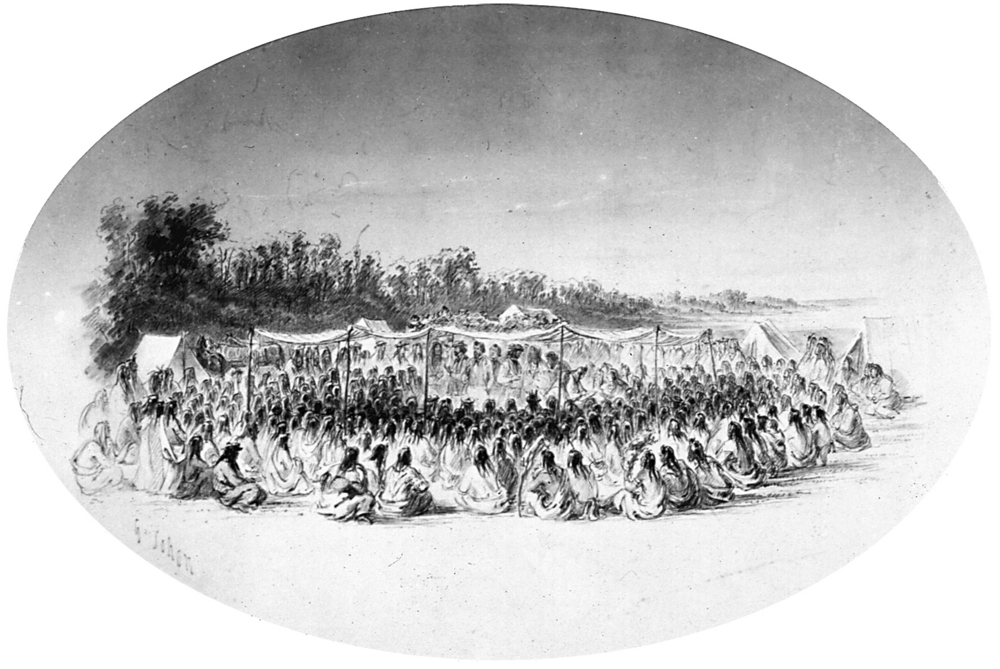

The Wenaha was within the territory of Nez Perce, Cayuse, Walla Walla, and Umatilla peoples. The Cayuse and Umatilla had a camp at the confluence of the north and south forks of the river, where they speared salmon and trout and gathered berries. From the 1820s through the 1840s, the Hudson’s Bay Company tapped the Wenaha region for furs and established a trading post about five miles downstream from the river’s mouth at a place known as Lost Prairie, on a bluff above the Grande Ronde River.

At the Walla Walla Treaty Council of 1855, Wallowa Nez Perce Chief Tuekakas, also known as Old Joseph, insisted that the Wenaha be included within the Nez Perce reservation. The Wenaha portion of the 1855 treaty was deleted in the second Nez Perce treaty in 1863, and by 1880 white cattle graziers and shepherds had moved into the basin. At the time, the Wenaha was also known as the Little Salmon River, a name that was dropped because of the larger Salmon River in present-day Idaho.

From 1880 to 1910, the thousands of sheep grazing the northern Blue Mountains devastated the environment. The 1906 Forest Inspector’s Report for the Wenaha Forest Reserve stated that the Wenaha country was no longer good for wild game. Market hunting, habitat destruction through overgrazing, and subsistence hunting by non-Natives decimated the wild game resource. Deer and elk, in the absence of enforced wildlife protection laws, had been almost completely hunted out. Further, the report surmised that bighorn sheep that lived along the basalt benches might be extinct.

The Oregon conservation scene changed through the vision of conservation-minded Governor Oswald West. In 1912 and 1913, his chief game warden, William L. Finley, expedited the transport of twenty-seven elk from Yellowstone National Park to Billy Meadows in northern Wallowa County, where their numbers increased rapidly. Thereafter, elk were successfully relocated throughout the Wenaha-Wallowa region. By 1945, the wide use of synthetic fabrics had reduced the demand for wool, and fewer domestic sheep were grazing in the drainage. Bighorn sheep and Rocky Mountain goats were transplanted into the Wenaha basin in 1984 and 2009. By 2018, the goat population had more than tripled to sixty animals, and the Bighorn population was estimated to be just over a hundred.

With passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964, groups such as the Wilderness Society, Oregon Wild, and Maintain Eastern Oregon Wilderness lobbied Congress for protection of the river. The river was entirely free flowing and was a viable fishery for spring Chinook, summer steelhead, and bull trout, making it a strong candidate for wilderness protection. In 1978, the Endangered American Wilderness Act designated all but the last six miles of the river as part of the Wenaha–Tucannon Wilderness Area. The river is now one of Oregon’s premier wildlife areas, with wolves and Shiras moose, both rare in Oregon, living in the basin. Some anglers consider the bull trout fishing on the Wenaha to be the finest in Oregon.

The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife manages the Wenaha Wildlife Area, which is primarily on the south side of the river. The Umatilla National Forest stewards over two hundred miles of trail in the wilderness, giving the Wenaha its reputation as one of Oregon’s outstanding hunting and backpacking destinations. One of the most traveled routes is the Wenaha River Trail, a twenty-two-mile-long undulating path from Troy to the Wenaha Forks. Deer, elk, and bighorn sheep—as well as rattlesnakes—are all resident on the ponderosa pine and balsamroot hillsides and canyon walls, and the trail sometimes hugs the river and sometimes contours over a hundred feet above it. The Grizzly Bear Complex Fire of 2015 destroyed the bridge that crossed Crooked Creek, making the river trail more of a challenge.

-

![]()

Wenaha confluence, 1940.

Courtesy University of Oregon Libraries, Zell Parkhurst, photographer -

![]()

Wenaha River, Troy, Oregon, 1940.

Courtesy University of Oregon Libraries -

![]()

Blue Mountains.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi13937

Related Entries

-

![Blue Mountains]()

Blue Mountains

The Blue Mountains, perhaps the most geologically diverse part of Orego…

-

![Heinmot Tooyalakekt (Chief Joseph) (1840-1904)]()

Heinmot Tooyalakekt (Chief Joseph) (1840-1904)

Heinmot Tooyalakekt (Thunder Rising to Loftier Mountain Heights), also …

-

![National Wild and Scenic Rivers in Oregon]()

National Wild and Scenic Rivers in Oregon

The world's first and most extensive system of protected rivers began w…

-

![Native American Treaties, Northeastern Oregon]()

Native American Treaties, Northeastern Oregon

After American immigrants arrived in the Oregon Territory in the 1840s,…

-

![Walla Walla Treaty Council 1855]()

Walla Walla Treaty Council 1855

The treaty council held at Waiilatpu (Place of the Rye Grass) in the Wa…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Allen, E.T. "Wenaha Forest Reserve, Forest Inspectors Report for 1906." Pomeroy: Umatilla National Forest, Supervisor’s Office Silviculture Library Archives, 1906.

Hunn, Eugene S., E. Thomas Morning Owl, Philip E Cash Cash, Jennifer Karson Engum. Caw Pawa Laakani—They Are Not Forgotten: Sahaptian Place Names Atlas of the Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla. Tamastslikt Culture Institute and Eco Trust. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2015.

Solomon, Christopher. "Runnin With the Bulls or Oregon's Wenaha River. Outside.

Palmer, Tim. Field Guide to Oregon Rivers. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2014.

Tucker, Gerald. History of the Northern Blue Mountains. Pomeroy: Umatilla National Forest, Supervisor’s Office Silviculture Library Archives.