After American immigrants arrived in the Oregon Territory in the 1840s, representatives of the United States established policies for Indigenous peoples in northeastern Oregon. By that time, the government had honed its policies and protocols in dealing with Native people, which included treaties, war, removal, and concentration on reservations. In northeastern Oregon, officials acting on behalf of the United States invited Indians to treaty councils, where they were urged to accept treaties and surrender much of their homeland. The government said treaties would prevent bloodshed with white settlers who were eager to resettle Native lands. Under the terms of the treaties, people from many tribes secured for themselves a minute portion of their former estates and lost valuable resources that they considered to be part of their spiritual birthright, including land, fish, game, roots, berries, minerals, timber, and water.

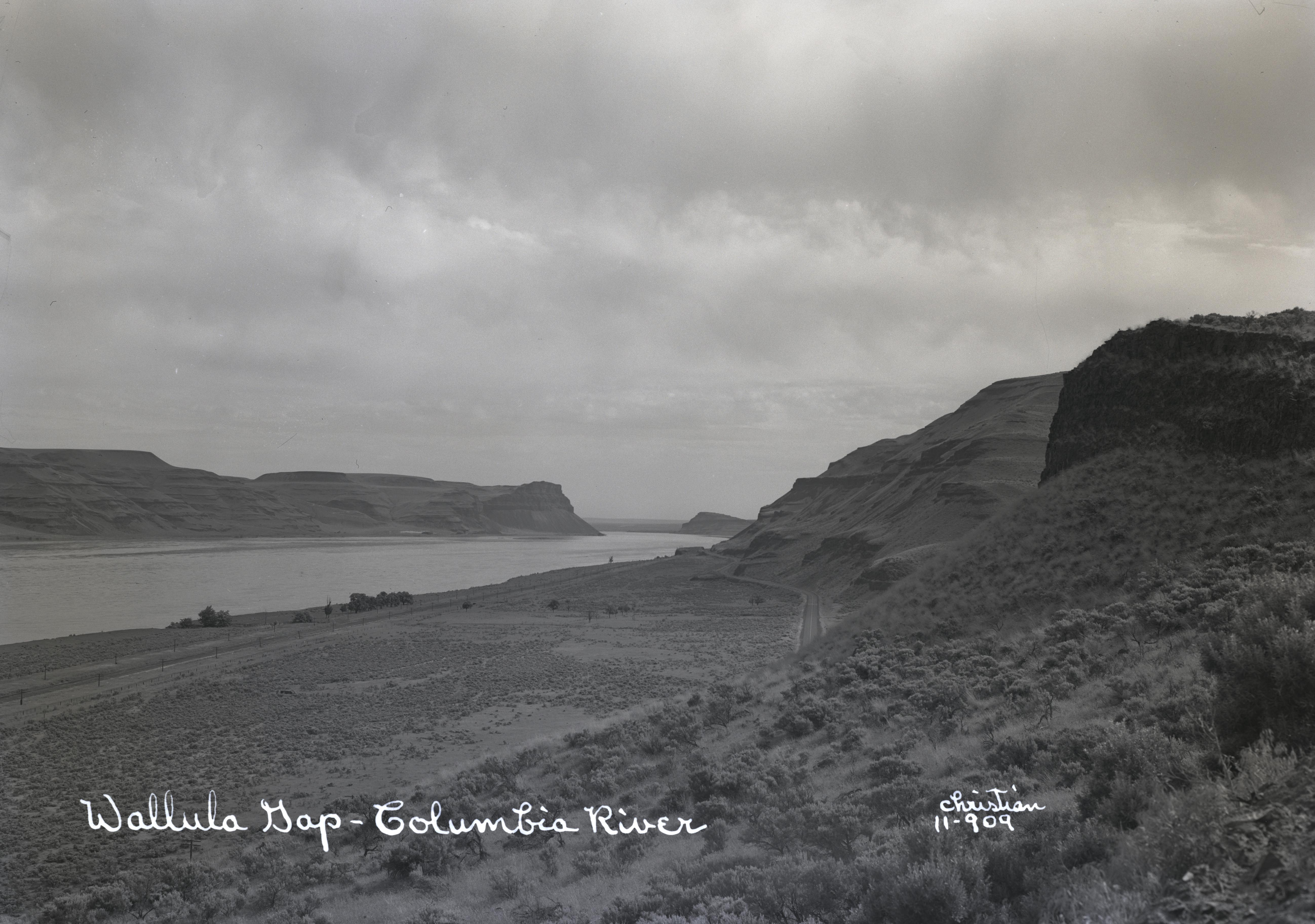

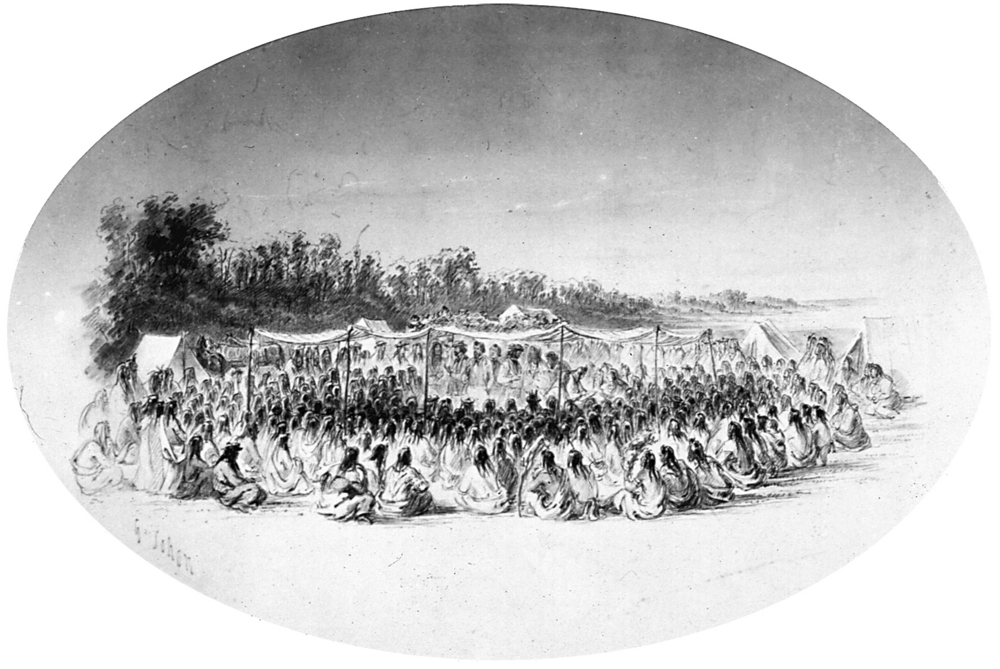

Walla Walla Council, 1855

Congress created Washington Territory in 1853 by slicing off the northern portion of Oregon, which created a smaller Oregon Territory made up of present-day Oregon, southern Idaho, and part of Wyoming. In late May 1855, the Walla Walla Council was convened at Camp Stevens in the Walla Walla Valley, where Joel Palmer, superintendent of Indian Affairs for the territory, joined Isaac Stevens, superintendent of Indian Affairs and governor of Washington Territory, to negotiate treaties with some of the tribes of eastern Oregon and Washington.

After the dramatic arrival of thousands of Indians in the Walla Walla Valley in late May, Palmer and Stevens opened the council that would forever change the lives of the region’s Indigenous people. Two thousand men, women, and children set up tipis near the council grounds at Waiilatpu, the Place of the Rye Grass, west of present-day Walla Walla, Washington. Palmer promised to protect tribal people with treaties designed to establish boundaries that would keep white settlers off reservation lands. He also promised to establish learning centers on reservations where Indians could be “civilized” in white ways. He wanted to open roads to and through Indian lands, and he claimed that commerce and trade would benefit Indians and whites alike.

To accomplish these goals, Palmer and Stevens asked tribal leaders to sign treaties that would create the Umatilla Reservation for the Walla Walla, Cayuse, and Umatilla; the Yakama Reservation for the Yakama, Palouse, Pisquouse, Klickitat, Wenatchi, Wishram, Klinquit, Kowwassayee, Liaywas, Skinpah, Shyike, Ochechote, Kahmiltpay, Seapcat, and others; and the Nez Perce Reservation.

Treaties and Reservations in Eastern Oregon

The treaty council lasted many days. Palmer continually told the people that the government wished to protect them from unscrupulous settlers and to uplift them with permanent homes, hospitals, farms, mills, shops, and schools where their children could be assimilated. He offered food, goods, and money for the sale of their land. He promised that the treaties would allow Indians to hunt, fish, graze, and gather forever off the reservations in their “usual and accustomed” areas.

For days, they listened patiently to Palmer and Stevens. Their leaders included Nez Perce Chiefs Tuekakas (Old Joseph), Hallalhotsoot (Lawyer), and Apashwyákaikt (Looking Glass); Palouse Chiefs Kahlotus and Tilcoax; Walla Walla Chiefs Piyópiyo Maqsmáqs (Yellow Bird), Ictíxec (Stickus), Páaxat Qoqóoxnim (Five Crows), and Weyatenatemany (Young Chief); and Yakama Chiefs Kamiakin, Owhi, and Teias. When Native leaders presented their reaction to the proposals, they spoke of the sacredness of the Earth and their inability to sell land the Creator had given them. The Creator had “made all the earth,” Cayuse Chief Five Crows said. “He made us of the earth.”

Earth as Sacred

For Indian leaders, selling the land was a sin. Ictíxec (Stickus) compared the request to a person taking a nursing baby away from its mother and selling the mother, leaving the child without sustenance. He explained that the land “is our mother.” Weyatenatemany (Young Chief) reminded everyone that God had instructed the earth, plants, and animals “to take care of the Indians” and told Indigenous people “not to sell the land.” Piyópiyo Maqsmáqs (Yellow Bird) said that the proposals for treaties and reservations made him feel like a feather blowing in the wind. The people of northeastern Oregon were reluctant to sell their land because it violated their religion, but they understood the political reality of their situation.

Native leaders framed their views in spiritual terms, but they realized that they would have to make agreements, asking Palmer what the president proposed in terms of money, goods, and boundaries. At first, Palmer proposed that the Walla Walla, Cayuse, and Umatilla people live on the Nez Perce Reservation, but Indian leaders from eastern Oregon and Washington did not wish to leave their lands. Then Palmer offered them a separate treaty in northeastern Oregon that created the Umatilla Reservation. Although not enthusiastic, Walla Walla, Cayuse, and Umatilla leaders signed the treaty on June 9, 1855, creating the Umatilla Reservation but ceding 6.5 million acres of their homeland to the United States.

Over time, Nez Perce, Palouse, and other Indigenous people moved onto the Umatilla Reservation, often marrying tribal members. Several people relocated to the Umatilla Reservation following the Plateau Indian War in 1855-1858 and the Nez Perce War in 1877. The U.S. Senate ratified the Walla Walla, Cayuse, and Umatilla Treaty on March 8, 1859, establishing a nation-to-nation relationship between the confederated tribes and the federal government, a legal relationship that exists today.

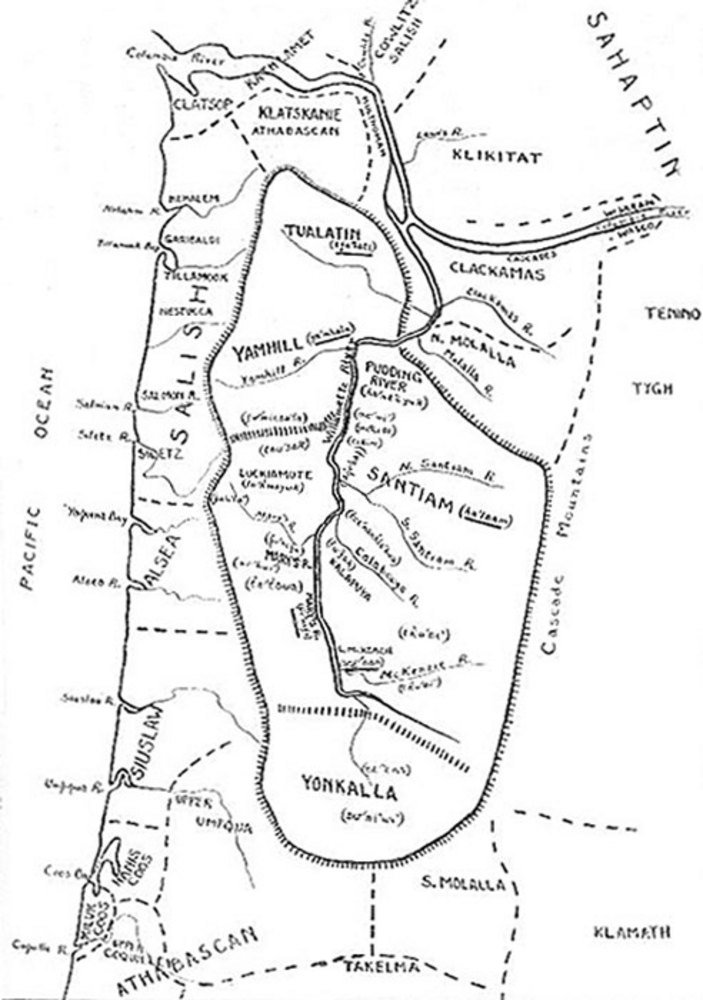

Middle Columbia River Council and Treaty

Not long after making this treaty, Palmer traveled down the Columbia River and met representatives of tribes of the middle Columbia River at the Wasco Treaty Council near The Dalles. Representatives of the Tenino, Tyigh, Wyam, Dockspuse, and Wasco came to the council knowing that Palmer wanted them to surrender lands and move to a reservation. They met at the Wasco village on the south side of the Columbia near Celilo Falls, where Palmer bluntly told them that he proposed a treaty to purchase their lands, extinguish title to their homelands and resources, and establish a reservation in the eastside foothills of the Cascade Mountains.

Palmer’s proposals were similar to those made earlier with the Walla Walla, Cayuse, and Umatilla: treaty, boundaries, tools, and assimilation through schools, hospitals, mills, farms, and teachers. He proposed to protect the people through treaties, warning them of dangerous white resettlers and hostile Indians. Chief Simtustus of the Upper De Chutes Band of Walla Walla Indians worried that the people would lose their fishery at Celilo Falls and would not be able to hunt and gather—the basis of their economy. Palmer told them they could forever fish, hunt, and gather off the reservation, a promise he included in the treaty. Even though the treaty guaranteed that the Indians could fish at all “usual and accustomed” areas, state officials later would ignore federal law and arrest Native fishers.

Chief Kickup of the Upper De Chutes Band of Walla Walla Indians agreed to move to the Warm Springs Reservation and “go and live where you have told us to go.” He was happy to live near whites, he said, since he did not feel “that it would do us any harm.” Wasco Chief Tohsimph did not trust Americans and wanted to be paid immediately for signing over his property, demanding, “We want the money now.” Palmer replied that he could not pay immediately, since government buyers could purchase blankets, tools, food, and supplies for Warm Springs people much cheaper than the Indians could if they purchased the goods from traders. With an understanding that they would be paid later and receive all they had negotiated, Indigenous leaders agreed to move south of the Columbia River to the Warm Springs Reservation.

Agreements and Disagreements

Several Native leaders signed the Wasco Treaty of June 25, 1855, including Simtustus, Locksquissa, Shickame, and Kickup (Upper De Chutes Walla Walla), Alexis and Talkish (Tenino Band of Walla Walla), Yise (John Day’s River Band of Walla Walla), Mark William Chenook and Cushkella (Dalles Band of Wasco), Tohsimph (Kigaltwalla Band of Wasco), and Wallachin (Dog River Band of Wasco). The U.S. Senate ratified the treaty and President Pierce signed it into law on March 8, 1858. Under the terms of the Wasco Treaty, the tribes surrendered approximately 10 million acres and agreed to move to the Warm Springs Reservation with a land base of 464,000 acres. The people lost land, resources, and fisheries, but until 1957 they continued to fish for salmon at their traditional fishing sites on the Columbia River, many of them working from platforms hanging over the roaring waters near Celilo Falls.

Not all Native people affected by the treaties agreed with them, and some refused to live on reservations. The Plateau Indian war began in 1855 in the wake of the treaty councils. After miners found gold near Colville, Washington, whites violated the treaty agreements by trespassing onto Indian lands north of the Columbia River, raping Native women and stealing horses. Native people retaliated by executing some miners. Indian Agent Andrew Jackson Bolon left The Dalles to investigate, but a party of Indians murdered him, triggering a war that put U.S. Army forces in the field to force resistant Native groups to surrender. Some Natives from northeastern Oregon participated in the war, fighting on and near the Columbia River and in Washington Territory.

Nez Perce War, Removal, and Native Economies

In 1858, Native warriors lost the battles of Four Lakes and Spokane Plain, and most people moved to the reservations. In 1877, the United States again used the army to force the Nez Perce onto a smaller reservation than specified in the 1855 treaty. Some warriors from the Warm Springs and Umatilla Reservations joined the Nez Perce in the fight against the United States. Although victorious in many battles, the Nez Perce, Cayuse, and Palouse lost the war in 1877. Gen. William T. Sherman, commanding general of the U.S. Army, forcefully punished Native combatants in the Nez Perce conflict, exiling them to Eekish Pah, the Hot Place of Kansas and Indian Territory. In 1885, some of the warriors who had participated in the Nez Perce War and had been exiled to Indian Territory returned with their families to settle on the Umatilla and Warm Springs Reservations, where their descendants live today.

In the late nineteenth century, the people of the Umatilla and Warm Springs Reservations continued to live by seasonal rounds—hunting, gathering, and fishing at particular times of the year. White resettlement of former Indian lands made this difficult, contributing to the decline and ultimate destruction of Native economies in northeastern Oregon. People on the Umatilla Reservation farmed the banks of the Umatilla River, but the poor soil and cool weather hampered farming on the Warm Springs Reservation. In order to survive, the people adapted, supplementing their traditional practices by working for white farmers, ranchers, merchants, and government agents and earning money as day laborers, rodeo riders, dancers, artisans, and actors.

Land, Fish, and Celilo Falls

Ostensibly to help Native people, reformers in Congress passed the General Allotment Act in 1887. The act proposed breaking up the reservations into small family parcels or allotments on the premise that Natives would work their allotments as farms and join the market economy. Reformers and capitalists in the West joined hands to pass the act, while cattlemen, farmers, miners, and entrepreneurs supported the bill because they believed it would open millions of acres of Indian land for white development. Agents allotted lands on reservations, including the Umatilla and Warm Springs Reservations, which reduced the amount of Indian land and did nothing to foster Native economic development.

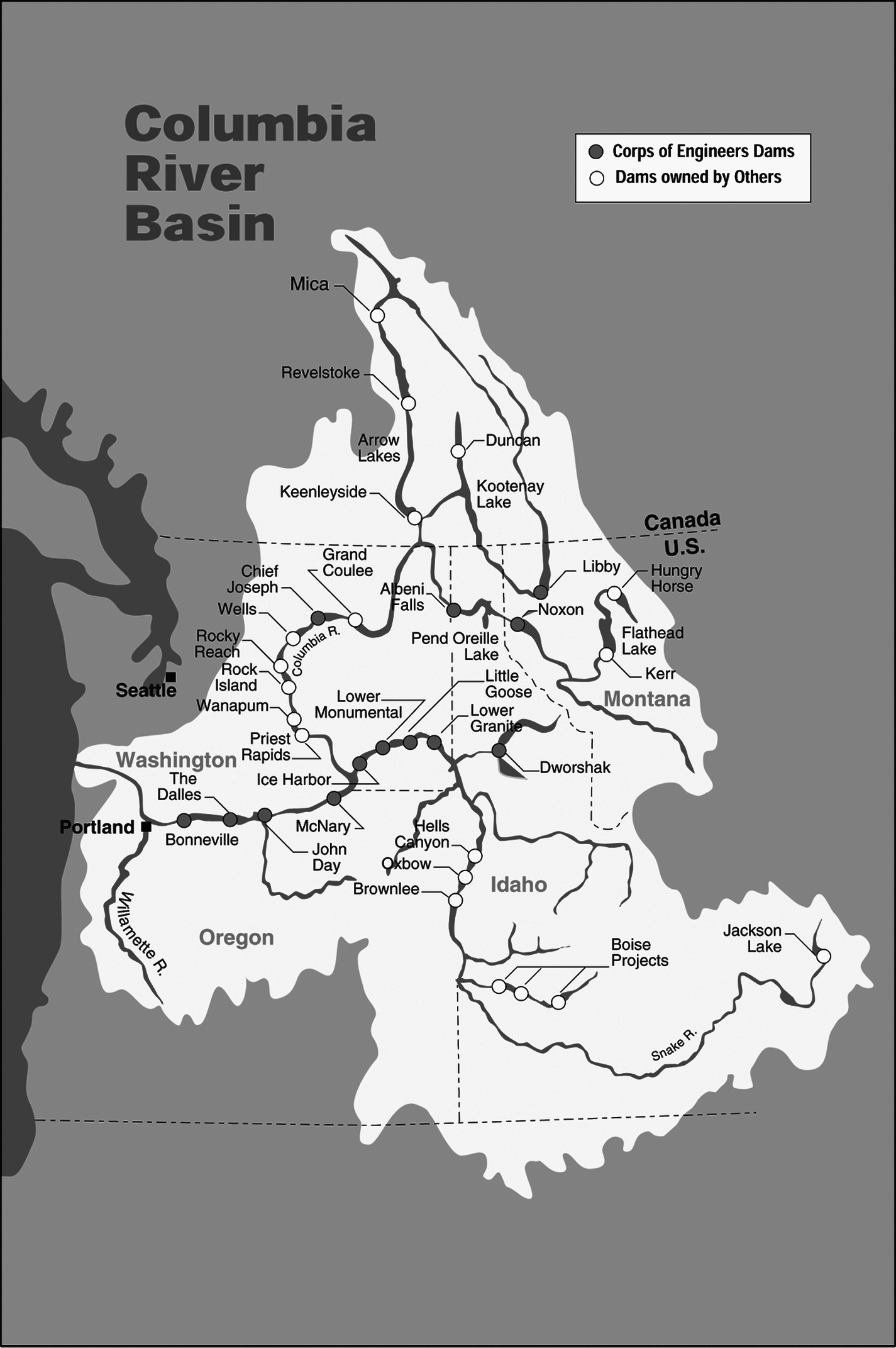

Twenty-two years before the passage of the Allotment Act, Warm Springs Indian Reservation Superintendent J.W. Huntington negotiated a new treaty, which diminished the size of the reservation but affirmed Native fishing rights. In further support of fishing rights in 1929, the government recognized Celilo Village, a seven-acre reserve on the Columbia River. The village is arguably the oldest continuously inhabited village of Native Americans in the United States, perhaps predating Acoma and Oraibi pueblos. But tragically for Indigenous people in eastern Oregon and Washington, in 1957 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built The Dalles Dam, which flooded the falls and destroyed the most important fishery on the Columbia River. Destruction of this sacred site remains a significant and painful loss to the people of the Warm Springs, Umatilla, and other reservations.

The inundation of Celilo Falls was the most dramatic and consequential disruption of Native fishing on the Columbia, but it was not the only dispute over Indian fishing rights in the Pacific Northwest. After World War II, Congress passed the Indian Claims Act in 1946, which permitted tribal governments to file claims against the government for the unauthorized theft of land and resources since the establishment of reservations in the 1850s. Northwest tribes petitioned the Indian Claims Commission in the U.S. Court of Claims to redress loss of resources. Tribes received small sums of money for their losses, but the government did not return land and resources. Nonetheless, a series of court cases including Sohappy v. Smith (1969), United States v. Oregon (1969), and United States v. Washington (1974), confirmed the Indians’ legal right to fish the Columbia and its tributaries.

Allotment and Sovereign Tribal Governments

In 1884, Paiute Chief Oytes led approximately seventy Northern Paiute onto the Warm Springs Reservation, where their descendants live today. Other Northern Paiute live on the Burns Indian Paiute Community in east-central Oregon.

In 1885, Congress passed the Slater Act, which implemented land allotments on a Midwest Indian reservation and the Umatilla Indian Reservation, preceding the General Allotment Act of 1887. Application of the Slater Act reduced Umatilla lands. In 1888, another act reduced the reservation with additional allotments, opening former reservation lands to non-Indians and reducing the Umatilla Reservation to 172,882 acres. On the Warm Springs Reservation, tribal members voted in 1937 to accept the Indian Reorganization Act (1934), better known as the Wheeler-Howard Act. By accepting the act, the people of Warm Springs reorganized their tribal government with bylaws and a constitution. In 1938, the people adopted the name Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation.

While the Warm Springs Reservation accepted the Wheeler-Howard Act, the people on the Umatilla Reservation rejected it. They decided to create a nine-member board of trustees and a general council, thus creating their own form of government that exists today. In 1949, people on the Umatilla Reservation followed the example of the Warm Springs people by renaming themselves the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation. Although the confederated tribes received funds through legal actions of the U.S. Claims Commission and Court of Claims, the United States government did not restore tribal lands or resources.

Fishing Rights and Modern Tribes in Eastern Oregon

In 1977, the tribal governments of the Umatilla, Warm Springs, Yakama, and Nez Perce Reservations established the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, which ensured “a unified voice” to protect sovereign rights, protect fish and watersheds, support tribal management and scientific research, and educate people about Salmon Culture. Salmon remains part of the spiritual life of the Native peoples of northeastern Oregon, and many people participate today in First Salmon ceremonies in traditional longhouses.

During the twentieth century, the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs could no longer survive on a traditional economy, so members worked at various jobs, and the tribes sold lumber and established recreational sites. It built Kah-Nee-Ta Resort in 1971 and added a casino in 1995, which helped fund housing, businesses development, education, and cultural-language programs. The Museum at Warm Springs opened in 1993 with exhibits on tribal history and Plateau Native American art and artifacts.

In 1998, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation opened Tamástslikt Cultural Institute, with 45,000 square feet of space housing an archive, library, exhibits, offices, café, and program area. The tribes’ programs, resort hotel, restaurant, and Wild Horse Casino employ thousands of people. The people of Warm Springs and Umatilla continue to meet in their longhouses to give thanks. Their treaties and policies provide permanent homelands and tribal sovereignty for modern Native nations of northeastern Oregon.

-

![]()

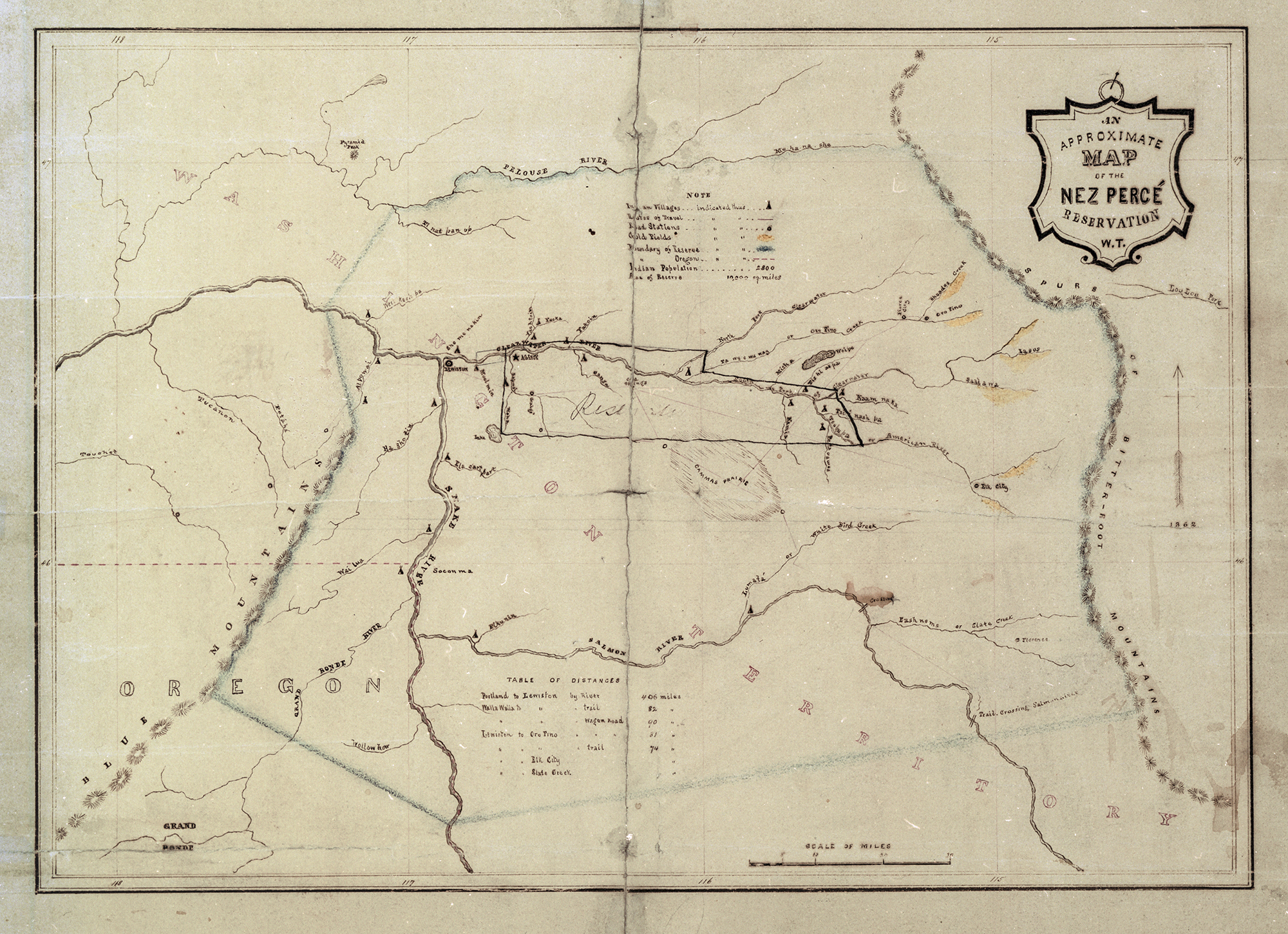

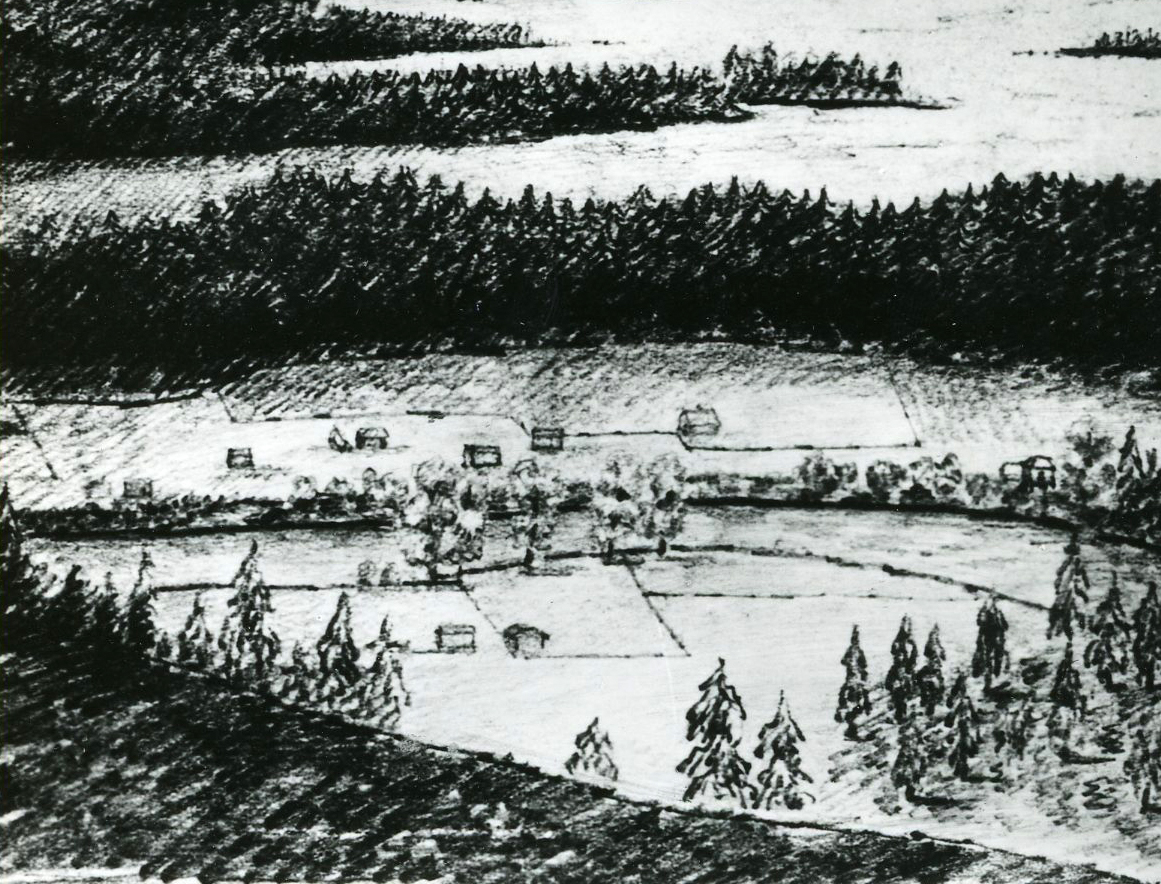

Approximate map of Nez Perce Reservation, c. 1855.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb014187

-

![]()

Chief Kamiakin, sketch by Gustavus Sohon, 1855.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi4349

-

![]()

Chief Five Crows, sketch by Gustavus Sohon, 1855.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi4359

-

![]()

Chief Lawyer, sketch by Gustavus Sohon, 1855.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi4346

-

![]()

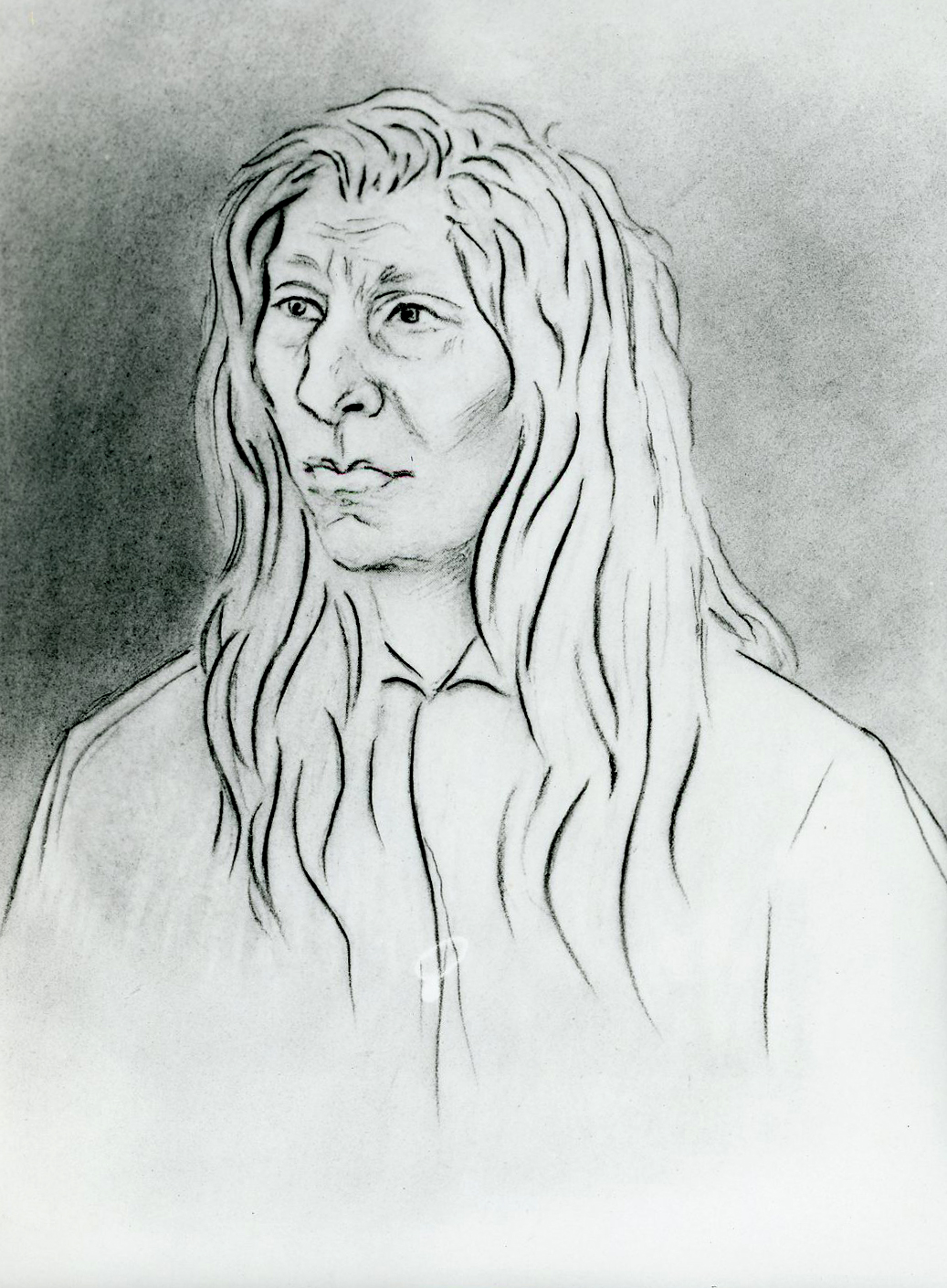

Old Chief Joseph, sketch by Gustavus Sohon.

Courtesy Washington State History Museum

-

![]()

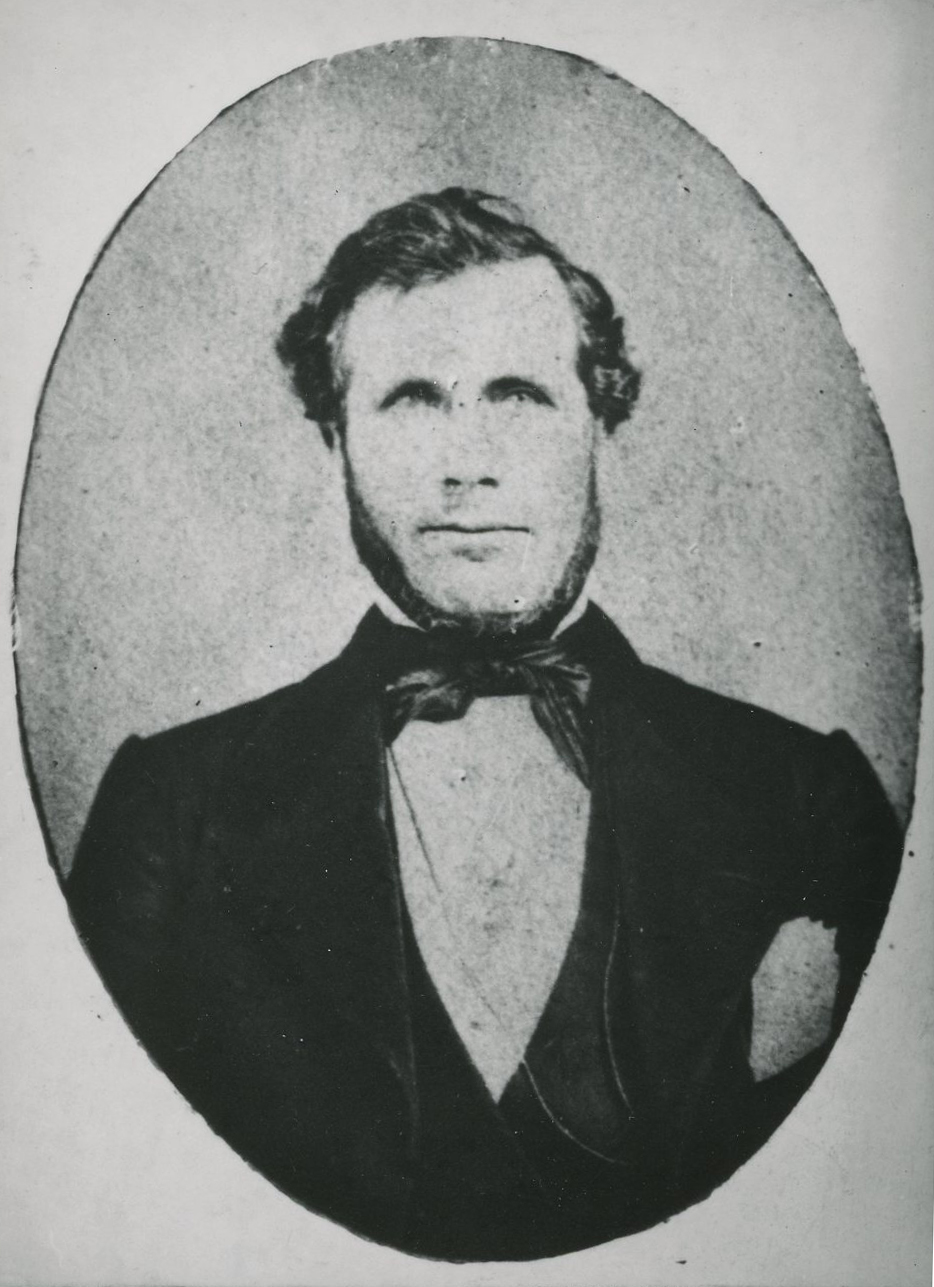

Joel Palmer, c.1860.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi362

-

![]()

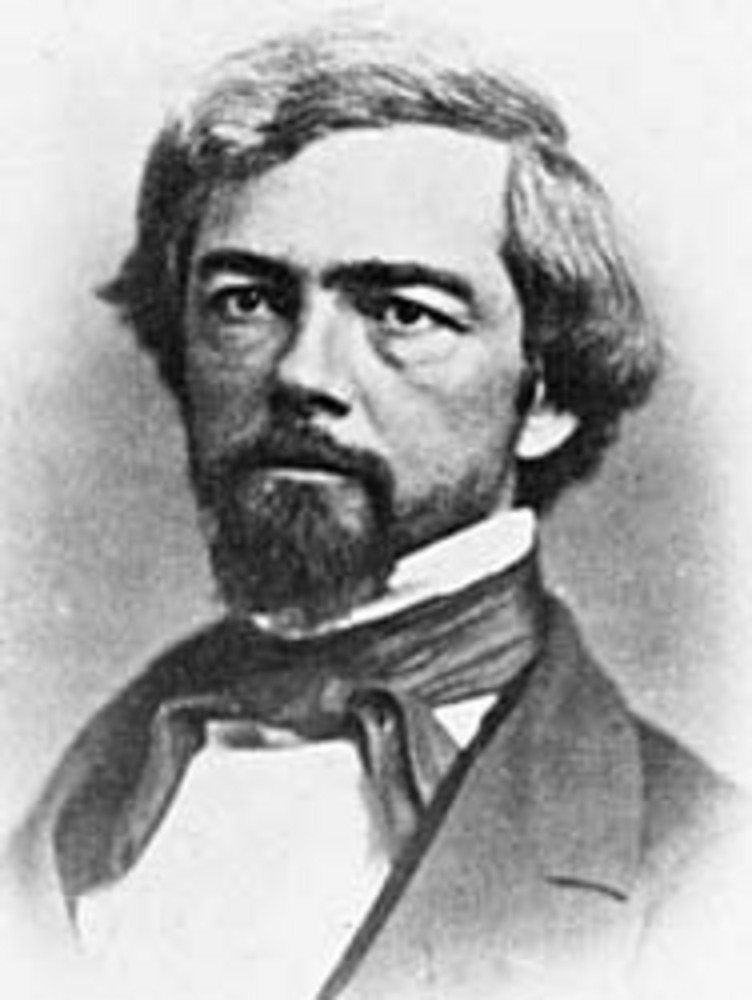

Isaac Ingalls Stevens (1818-1862).

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, ba001214

Related Entries

-

Celilo Falls

Celilo Falls (also known as Horseshoe Falls) was located on the mid-Col…

-

![Columbia River Treaty (1964)]()

Columbia River Treaty (1964)

The high-voltage power lines that march across central Oregon, linking …

-

![Heinmot Tooyalakekt (Chief Joseph) (1840-1904)]()

Heinmot Tooyalakekt (Chief Joseph) (1840-1904)

Heinmot Tooyalakekt (Thunder Rising to Loftier Mountain Heights), also …

-

![Isaac Ingalls Stevens (1818-1862)]()

Isaac Ingalls Stevens (1818-1862)

Isaac Stevens strode through the Northwest's formative years (1853-1861…

-

![Kalapuya Treaty of 1855]()

Kalapuya Treaty of 1855

The treaty with the Confederated Bands of Kalapuya (1855) is the only r…

-

![Walla Walla Basin]()

Walla Walla Basin

Long before the wheat and cattle ranches, the orchards and onion farms,…

-

![Walla Walla Treaty Council 1855]()

Walla Walla Treaty Council 1855

The treaty council held at Waiilatpu (Place of the Rye Grass) in the Wa…

-

![Willamette Valley Treaties]()

Willamette Valley Treaties

From 1848 to 1855, the United States made several treaties with the tri…

-

![Willamette Valley Treaty Commission]()

Willamette Valley Treaty Commission

On June 5, 1850, An Act Authorizing the Negotiation of Treaties with th…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Kappler, Charles J. Indian Affairs, Laws and Treaties, 2 Volumes. Washington, D. C.: Government Printing Office, 1940.

Kip, Lawrence. Indian Council at Walla Walla. Seattle: The Shorey Book Store, 1971.

Kip, Lawrence. Army Life on the Pacific; Journal of the Expedition Against the Northern Tribes of the Coeur d’Alene, Spokanes, and Pelouzes, in the Summer 1858 (New York: Redfiled Publishing Co., 1859, reprint, Clifford E. Trafzer, editor, Indian War in the Pacific Northwest: The Journal of Lawrence Kip, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999.

Pambrun, Andrew. Sixty Years on the Frontier in the Pacific Northwest. Fairfield, Washington: Ye Galleon Press, 1978.

Richards, Kent. Isaac I. Stevens: Young Man in a Hurry. Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1979.

Ruby, Robert H., John Brown, and Cary C. Collins. A Guide to the Indian Tribes of the Northwest. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010.

Trafzer, Clifford E. “Earth, Animals, and Academics: Plateau Indian Communities, Culture, and the Walla Walla Council of 1855." American Indian Culture and Research Journal 17, Number 3, (1993): 81-100.

Trafzer, Clifford E. “Legacy of the Walla Walla Council, 1855." Oregon Historical Quarterly 106, Number 3, (Fall 2005): 398-411.

Trafzer, Clifford E. and Richard D. Scheuerman. Renegade Tribe: The Palouse Indians and the Invasion of the Inland Pacific Northwest. Pullman: Washington State University Press, 1986. Reprint, The Snake River Palouse and the Invasion of the Inland Pacific Northwest, 2016.

Trafzer, Clifford E., editor. Indians, Superintendents, and Councils: Northwestern Indian Policy, 1850-1855. Landham, Maryland: University Press of America, 1986.