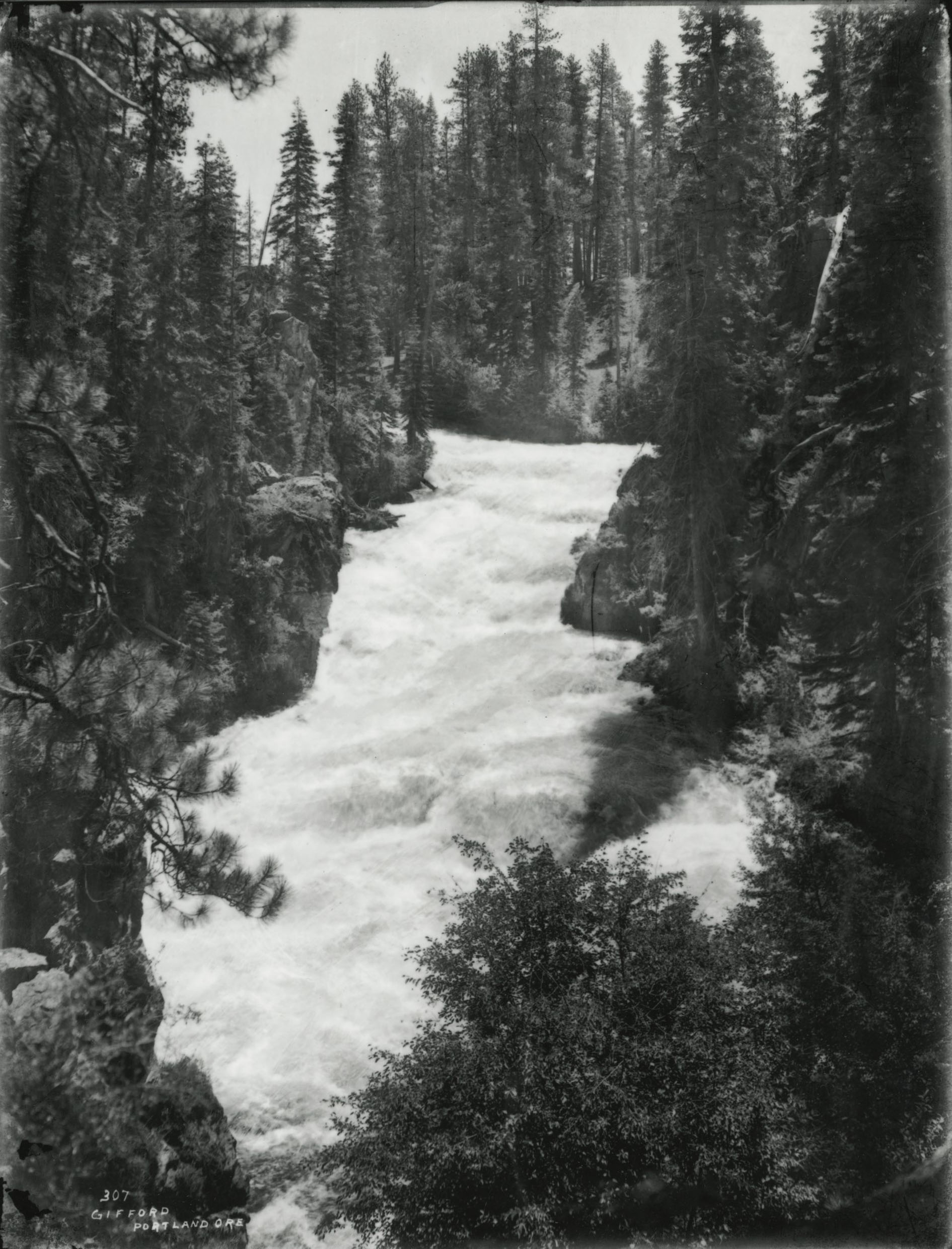

From its headwaters on Steens Mountain, the Donner und Blitzen River winds northwest for 78 miles through public lands and a variety of ecosystems to its termination in Malheur Lake. The river drains over 200 square miles through deep, glacially carved mountain valleys and the marshy Blitzen Valley, collecting water from numerous tributaries. The watershed supports more than 250 species of wildlife, including redband trout and Malheur mottled sculpin, and provides water for agriculture, ranching, and recreation operations in southeastern Oregon. Commonly referred to as the Blitzen River, the Donner und Blitzen possesses outstanding characteristics that led to its national designation as a wild and scenic river. Today, thousands of recreational visitors use the river each year for fishing, birdwatching, and camping, through adjacent land managed by federal and state land management agencies.

The Donner und Blitzen has played an important role in the lives and cultures of Indigenous people for millennia, and more than a dozen riverine archaeological sites indicate over 8,000 years of human association with the river. Regional tribes—including the Burns Paiute, the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, and the Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribes—remain connected to the river, and tribal members regularly use nearby traditional resource areas for activities that include hunting, fishing, gathering berries and edible roots, and collecting grasses for basketry.

The river’s modern name is its second of military origin, stemming from U.S. Army incursions that began in 1860. On a campaign against Northern Paiutes that August, Major Enoch Steen reported encountering “a bold mountain stream” possessing “remarkable beauty,” which he named the New River. The name was published on the 1860 U.S. Topographical Engineers’ map of eastern Oregon and was listed on maps as late as 1870.

Capt. George B. Currey and his detachment of volunteers in the First Oregon Cavalry, traveling from Camp Alvord to Harney Lake in June 1864, found themselves waylaid by a “deep, sluggish creek” south of Malheur Lake. They were forced upstream in search of a ford, which they found near a muddy tributary. “At the moment we reached the banks of this stream,” Currey reported, “a loud clap of thunder sounded over our heads, from which incident we named the stream ‘Thunder River.’ The smaller stream, for the sake of euphony, we called ‘Blitzen River’,” he added, applying the German word for lightning, which often accompanies thunder. An explanation for Currey’s use of German has yet to be found, though one historian attributes it to “the well-read colonel remember[ing] his German lessons.” On his return to Camp Alvord, Currey trekked to the headwaters of what he called Thunder Creek, where he observed “several small lakes and valleys.”

Subsequent nineteenth-century maps identify the river as New, Thunder, and Dunder und Blitzen, the last an apparent combination of Currey’s names for the main river and its tributary and the words dunder and donner, which derive from the Dutch and German words for thunder. By 1879, Dunder und Blitzen had become mapmakers’ standard, and the name appeared in an interpretation of Currey’s report in Hubert Bancroft’s History of Oregon (1888). Donner had replaced Dunder on maps by century’s end. The U.S. Geographic Names Information System listed the river’s name as Donner und Blitzen on November 28, 1980.

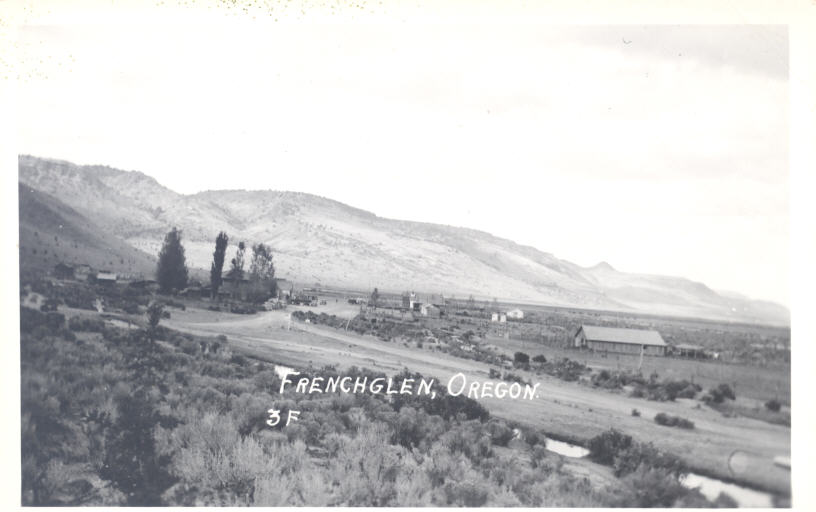

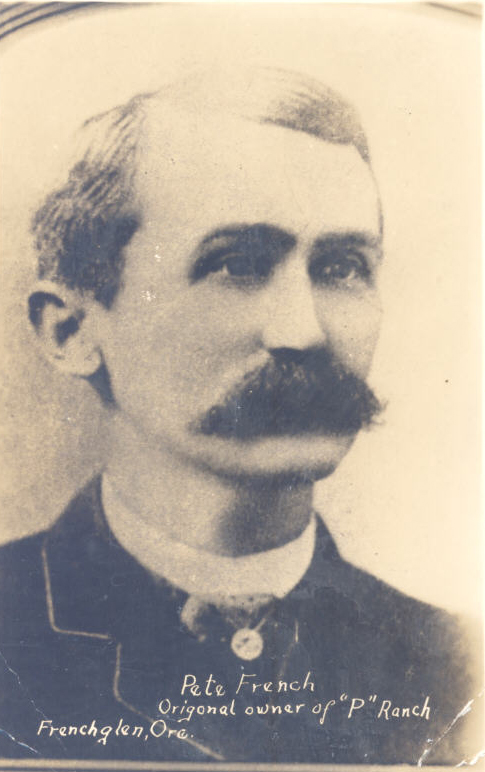

Human alteration of the river began in 1872 with the arrival of John William “Pete” French, who established the P Ranch along the river’s lower course through what became known as the Blitzen Valley. French and his employees dug several ditches to drain the river’s wetlands—a hazard to rangeland cattle—and to increase grassland for grazing, and he ultimately fenced many miles of the river’s banks. Both the P Ranch and the Riddle Brothers Ranch on the Little Blitzen are National Historic Districts and are listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

Dissolution of the P Ranch in 1897 began to refocus land use in the Blitzen Valley from ranching to agriculture, especially hay farming, which demanded more of the river. By 1904, the Census Bureau reported that the Donner und Blitzen provided water to 53 farms irrigating 34,701 acres through 25 systems, whose main canals and ditches totaled 54 miles. Establishment of the Malheur Lake Bird Reservation by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1908 included the lake only. By 1910, subsequent development—centered on a 40-mile-long canal—had drained over 80,000 acres of swampland in the Blitzen Valley. In May 1935, the Eastern Oregon Livestock Company sold 64,000 acres of the Blitzen Valley to the federal government for what would become the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, formalizing federal ownership of forty-five miles of the river’s banks.

The river’s name is not its only unique feature. Another is its high-altitude headwater region. Studies suggest that snow high on Steens Mountain and in its canyons routinely delays the watershed’s peak drainage until May and June, later than all other area sub-basins, to a period optimum for fledging of nesting species and the production of grasses for grazing animals.

The Donner und Blitzen inspired artists, including Frederic Remington, who reportedly lodged at the P Ranch, and Childe Hassam, who camped along the river for two months in 1908, producing 40 works of art, several of which were first exhibited at the Portland Art Museum later that year.

Completion of the Steens Mountain Loop Road in 1962 by the Bureau of Land Management opened recreational access to the upper river and its tributaries, and the 1972 designation of the Steens Mountain Recreation Lands increased access to the river’s fishing, hiking, backpacking, and camping opportunities.

On March 4, 1988, Oregon Senator Mark O. Hatfield introduced S. 2148, the Omnibus Oregon Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1988. Cosponsored by Oregon Senator Bob Packwood, it proposed adding forty Oregon rivers, including the Donner und Blitzen, to the national wild and scenic river system. With support from Oregon Representatives Peter A. DeFazio, Ron Wyden, and Les AuCoin, the Mark O. Hatfield Oregon Wild and Scenic Rivers Act became Public Law No. 100-557 on October 28, 1988. The law gave wild status to the 16.75-mile segment of the Donner und Blitzen, from its confluence with the South Fork Blitzen and Little Blitzen, plus segments of five of its tributaries: the Little Blitzen, the South Fork Blitzen, Big Indian Creek, Little Indian Creek, and Fish Creek.

The Steens Mountain Cooperative Management and Protection Area Act, passed in 2000, expanded the river’s wild and scenic status by 14.8 miles through designating new sections of tributaries Mud Creek, Ankle Creek, and the South Fork of Ankle Creek. It also established the 170,024-acre Steens Mountain Wilderness, adjacent to and including the river and its tributaries, and designated a 97,671-acre No Livestock Grazing area, primarily within the river’s watershed. Finally, it created the Donner und Blitzen Redband Trout Reserve for the purposes of conserving, protecting, and enhancing redband trout and providing opportunities for research, education, and recreation in partnership with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Today, much of the river traverses public land managed by the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service and the U.S. Bureau of Land Management.

-

![]()

Donner und Blitzen River, 2016.

Courtesy Bureau of Land Management, photo by Greg Shine

-

![]()

Conversion dam for irrigation on the Donner und Blitzen, Malheur Bird Refuge, 1937.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Journal, Walt Sperling, pf474a

-

![]()

Donner und Blitzen River, 2016.

Courtesy Bureau of Land Management, photo by Greg Shine

-

![]()

Donner und Blitzen River, 2016.

Courtesy Bureau of Land Management, photo by Greg Shine

-

![]()

South Fork Donner und Blitzen Wilderness Study Area, 2016.

Courtesy Bureau of Land Management, photo by Greg Shine

Related Entries

-

![Frenchglen Hotel]()

Frenchglen Hotel

Frenchglen is a small desert community sixty miles south of Burns whose…

-

![John William "Pete" French (1849-1897)]()

John William "Pete" French (1849-1897)

Peter (or Pete) French was a stockman of near-legendary status who ran …

-

![Malheur National Wildlife Refuge]()

Malheur National Wildlife Refuge

Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, established in 1908 by President Theo…

-

![National Wild and Scenic Rivers in Oregon]()

National Wild and Scenic Rivers in Oregon

The world's first and most extensive system of protected rivers began w…

-

![Steens Mountain]()

Steens Mountain

Rising to an elevation of 9,733 feet, Steens Mountain is the highest po…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Langston, Nancy. Where Land and Water Meet. Seattle: Univ. of Washington Press, 2006.

Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, Proposed Resource Management Plan and Final Environmental Impact Statement, Vol. 1, Andrews Management Unit / Steens Mountain Cooperative Management and Protection Area, (Burns, Ore., 1992), 3-37.

Palmer, Tim. Field Guide to Oregon Rivers. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2014.

"Letter of August 18, 1860, Major Enoch Steen to Captain James A. Hardie.” In Oregon Indians: Voices from Two Centuries, edited by Stephen Dow Beckham, 179. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2006.

Clark, Robert. "Harney Basin Exploration, 1826-60." Oregon Historical Quarterly 33.2 (1932): 113-4.

Currey, George B. “Report of Capt. Geo. B. Currey, of Company ‘E,’ O.V.C.” In Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of Oregon, for the Years 1865-6, 41. Portland, Ore. Henry L. Pittock, State Printer, 1866.

French, Giles. Cattle Country of Peter French. Portland, Ore.: Binfords & Mort, 1965).

The War Of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Vol. 50, Part 1. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1897.

“Works of Childe Hassam on Exhibit at Museum of Art.” Morning Oregonian November 9, 1908, 7.