Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, established in 1908 by President Theodore Roosevelt, lies in the Great Basin landscape of eastern Oregon, thirty-five miles south of Burns in Harney County. With nearly 188,000 acres of wetland, riparian, and upland habitats on the Pacific Flyway, Malheur is a key migratory stopover habitat for millions of birds. Before the refuge was established, commercial hunting and habitat loss from drainage and reclamation had devastated waterbird populations in North America. The restoration of Malheur’s wetlands in the 1930s served as a state and national model for avian conservation. In addition, fifty-eight species of mammals use the refuge, including fourteen species of bats, mule deer, pronghorn antelope, cougar and bobcats, and Rocky Mountain elk. Archeological sites attest to the richness of Native American culture in the region. Refuge headquarters, for example, is within a key settlement site used seasonally by the Paiute for thousands of years. National historic sites in the refuge include the Sod House Ranch property, built by the nineteenth-century cattle baron Peter French.

The Northern Paiute people lived in eastern Oregon—including on land that would become the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge—for thousands of years until the federal government forced them off their lands in 1872. They were removed and confined to the Malheur Reservation, where a section of the refuge is now located. In 1877, President Ulysses S. Grant ordered the northern shores of Malheur Lake, on the reservation, opened to white resettlement, making it nearly impossible for the Paiute to continue gathering wada seeds (Suaeda calceoliformis), which were important for their survival.

When the Paiutes joined the Bannock Uprising in 1878, retaliation was brutal and swift. Federal troops forced the Paiute survivors to march 350 miles through the snow to the Yakama Reservation, the home of tribes long hostile to them. In 1879, President Grant abolished the Malheur Reservation and restored the remaining lands to the public domain.

California cattle barons such as Peter French moved livestock onto reservation lands after the 1878 uprising, even before the land had been made public. Malheur Lake and the Blitzen River watershed became the center for what was briefly the largest cattle empire in America and what became some of the bitterest battles among cattle barons, Indians, homesteaders, irrigators, ranchers, and environmentalists—all focused on who would control the riparian areas.

Peter French consolidated his holdings until he controlled nearly all the water sources and riparian areas in the Blitzen Valley. Homesteaders also were trying to lay claim to these landscapes, and conflicts soon erupted into violence. In the wake of intensifying competition, cattle barons and homesteaders tried to survive by squeezing as many cattle as possible onto pastures. The result was severe overgrazing, the effects of which still scarred refuge lands decades later.

Tensions between cattle barons and poor homesteaders exploded in the 1890s. After French was shot and killed in the back by a homesteader in 1897, his cattle empire passed into the hands of speculators who subdivided the holdings for sale in small parcels. Promises to dredge the wetlands and irrigate the sagebrush uplands for small farmers soon failed, and the local economy struggled.

In 1905, Oregon conservationists William Finley and Herman Bohlman campaigned to save Malheur Lake from market hunting and further agricultural development to protect what was considered the greatest concentration of ducks, shorebirds, egrets, herons, cranes, and ibises in the Pacific Northwest. With the help of the Audubon Society of Portland, they persuaded President Theodore Roosevelt in 1908 to establish Malheur Lake Bird Reservation on unclaimed government lands encompassed by Malheur, Mud, and Harney Lakes “as a preserve and breeding ground for native birds.”

The new refuge, however, did not include the rivers that fed the lakes. During droughts, Malheur Lake shrank, and poor homesteaders moved onto the drying lakebed. Decades of legal disputes followed over ownership of the refuge lands. In 1934, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the lands belonged to the wildlife refuge, but tensions over contested ownership simmered well into the twenty-first century.

As Malheur Lake dwindled, Finley and Portland Audubon realized that they needed to acquire water rights to the Blitzen River to protect the refuge. The Federal Emergency Relief Program eventually released funds for the purchase, and on September 25, 1934, the owners of the former French ranchlands agreed to accept $675,000 from the federal government for 65,000 acres of the Blitzen River valley, including the water rights.

Three Civilian Conservation Corps camps operated on the Malheur Refuge from 1935 until 1942. More than a thousand young men worked at the camps, providing essential labor for wetland restoration and habitat improvement.

John Scharff, a local rancher who was manager of the Malheur Wildlife Refuge from 1935 to 1971, transformed local suspicion of the refuge into acceptance, largely by providing grazing leases on refuge land. Yet challenges remained, particularly when carp destroyed much of the waterfowl habitat in Malheur Lake by disrupting the ecosystem of plants and insects migratory birds rely on. Carp impacts have reduced migratory bird productivity over 90 percent, and the refuge research program focuses on understanding how invasive carp have affected aquatic health and developing ways to work with private landowners to control carp throughout the basin.

During the 1990s, the Burns Paiute Tribe, ranchers, environmentalists, and federal agencies began working across the boundaries that divided them, collaborating on innovative programs to reduce carp, restore waterfowl habitat, and use grazing as a management tool, while also giving ranchers more flexibility. In 2005, Refuge Manager Chad Karges co-founded the High Desert Partnership, which brought together ranchers, environmentalists, county officials, the Burns Paiute Tribe, and federal and state officials to plan for the future of the refuge. In 2013, those efforts resulted in a landmark conservation plan for the Malheur Refuge that has become a model for other regions.

The refuge gained international attention in January 2016 when armed insurrectionists occupied it, decrying federal control over Western lands. The group called on local ranchers to help them cast out the federal government, yet a majority of the local community supported the refuge. The forty-one-day occupation cost the federal government over $9 million and shut the refuge visitor center to the public for more than sixteen months.

Collaborative processes that brought together ranchers, tribes, environmentalists, and local community members continue to make the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge a showcase for efforts to incorporate local concerns with protection for wildlife.

-

![]()

Herman Bohlman scaring gulls, Malheur Lake, 1908.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrgLot369_FinleyA2070

-

![]()

White-faced Glossy Ibis, Malheur Lake, 1908.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrgLot369_FinleyA2132

-

![]()

Office of Malheur National Forest Building.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries, C.C. Hall Photo Album

-

![]()

Map of the Malheur Indian Reservation, 1879.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Map 132

-

![]()

Family of Bannock Indians, 1872,.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 45440

-

![]()

Oregon Journal, 1937, on Malheur Migratory Bird Refuge.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries, Finley

-

![]()

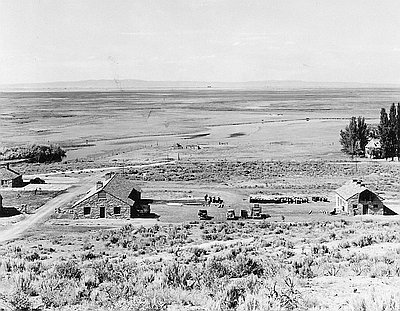

Sod House Ranch, Harney County, built by Pete French.

Courtesy University of Oregon Libraries

-

![]()

Flock of pelicans and gulls, Malheur Lake, 1908.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrgLot369_FinleyA2278

-

![]()

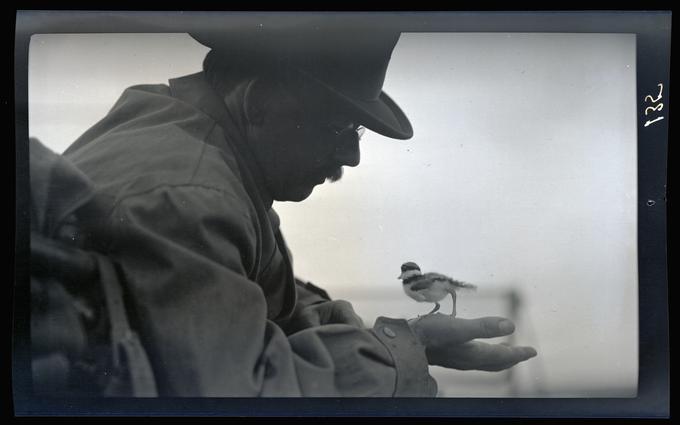

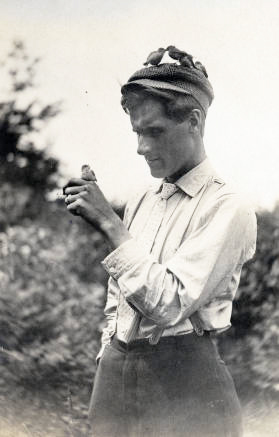

Dallas Lore Sharp holding a killdeer, Malheur Lake, 1912.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrgLot369_FinleyB0135

-

![]()

A shack on the north side of Malheur Lake, 1908.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrgLot369_FinleyA2188

-

![]()

William, Irene, and Phoebe Finley, mouth of Malheur Cave, 1917.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrgLot369_FinleyD0151

-

![]()

Pelicans and cormorants, Malheur Lake, 1919.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrgLot369_FinleyD0201

-

![]()

Malheur Bird Refuge, 1937.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi91097

-

![]()

White-faced Glossy Ibises over Malheur Lake, 1908.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrgLot369_FinleyA2151

-

![]()

Western Grebe, Malheur Lake, 1908.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrgLot369_FinleyA2025

Related Entries

-

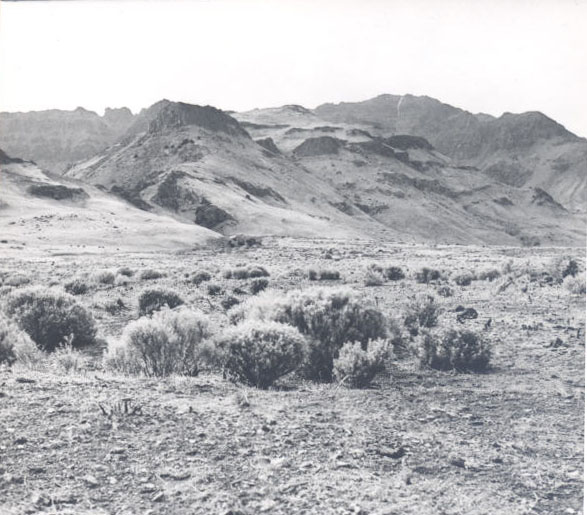

![High Desert]()

High Desert

Oregon’s High Desert is a place apart, an inescapable reality of physic…

-

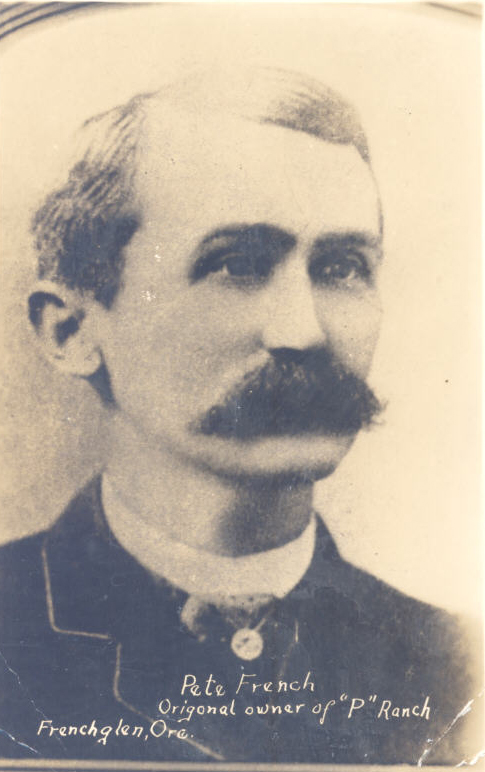

![John William "Pete" French (1849-1897)]()

John William "Pete" French (1849-1897)

Peter (or Pete) French was a stockman of near-legendary status who ran …

-

![William L. Finley (1876–1953)]()

William L. Finley (1876–1953)

Oregon's birds have had few better friends than William Lovell Finley. …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Harney Basin Wetlands Collaborative

Langston, Nancy. Where Land and Water Meet: A Western Landscape Transformed. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003.

Robbins, William. Landscapes of Promise: The Oregon Story 1800-1940. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997.

Malheur National Wildlife Refuge website