Before moving to Portland in the early years of the twentieth century, Edward Boyce was reviled in the city’s newspapers. As the first president of the Western Federation of Miners, he had expanded the range, power, and influence of the union, and the Oregonian called him a dangerous degenerate, a dynamiter, an anarchist, and an ex-con. One journalist labeled him a “foul-mouthed blatherskite.” Yet, when he died almost four decades later, not long after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, notice of Boyce’s death was one of the few local front-page stories to compete with news of World War II.

Born on November 8, 1862, in County Donegal, Ireland, Boyce made his way to the United States as a young man. By the early 1890s, he was working as a hard-rock miner in the Northern Rockies, and he was soon involved in attempts to organize miners to gain better pay and working conditions. In 1892, authorities detained Boyce and over a dozen other miners in a Boise, Idaho, jail. After their release, some of the men formed a core of workers who met in Butte, Montana, to charter the Western Federation of Miners (WFM). From its beginnings in 1893 until about World War I, the WFM was at the vanguard of radical labor unions in the United States.

Boyce spent three years organizing for the WFM before becoming its president in 1896. The union struck mines in the Leadville area of Colorado the following year, and Boyce found himself once again detained, ostensibly to protect him from thugs hired by mine owners. Two years later, during a dispute over wages at the Bunker Hill Mine in the Coeur d’Alene region, WFM members dynamited the ore concentrator at the site, killing two men. Boyce always denied having ordered the attack and confided to his journal that the incident would end effective organizing in the region. Idaho Governor Frank Steunenberg and local authorities largely succeeded in suppressing the union in the state, and for the next few years Boyce worked to organize WFM locals elsewhere. He was named editor of the union’s Miners' Magazine in 1900. He was drawn back to the region by a Coeur d’Alene schoolteacher named Eleanor Day.

Boyce and Day married in May 1901. About a month later, a mining claim she had invested in with her father and brother near Burke, Idaho, proved out, striking one of the richest silver deposits in the area and gaining the name Hercules. Boyce declined to run for reelection as WFM president in 1902 and ended his formal relationship with the union. By the time the couple moved to Portland in about 1904, the Hercules Mine was providing monthly dividends of over $2,000 on Eleanor’s share of the stake. The mine continued to produce ore for its investors into the 1920s, and by then the Days controlled about half the shares.

In Portland, the family invested in the Portland Hotel Company, and Boyce became president of the business in 1911, a position he would hold until his death. In 1906, the Boyces purchased a lot in the city’s West Hills and built a house, which still stands.

In 1907, Edward Boyce traveled to Idaho to testify in the trial of three WFM officers—William “Big Bill” Haywood, the general secretary of the WFM; Charles Moyer, WFM president; and miner George Pettibone—who were accused of planning the assassination of Idaho Governor Frank Steunenberg. For a time prior to and during the trial, he was under surveillance by operatives of the Thiel Agency, who had been hired by mining interests. His former colleagues beat the charges, and Boyce returned to Portland to pursue less controversial civic interests.

Over the following decades, Eleanor and Edward Boyce received frequent mention in the society pages of Portland newspapers—Edward traveled with the Royal Rosarians, set out to summit Mount Hood, served on a grand jury, introduced visiting politicians, and hosted U.S. presidents at the Portland Hotel. He also supported the United States’ entry into World War I and stood against the heightened influence of the Ku Klux Klan in Oregon during the 1920s. He put some of his mining background to practical use from 1931 to 1935 as chair of the Oregon Tunnel Commission. He was also chair of the Portland Hotel Association in 1936.

Edward Boyce died on Christmas Eve 1941. Eleanor Day Boyce outlived him by a little over a decade, dying in 1951. Their papers are held by the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture in Spokane.

-

![]()

Edward Boyce on the stand during the Haywood Trial, 1907.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 000252

-

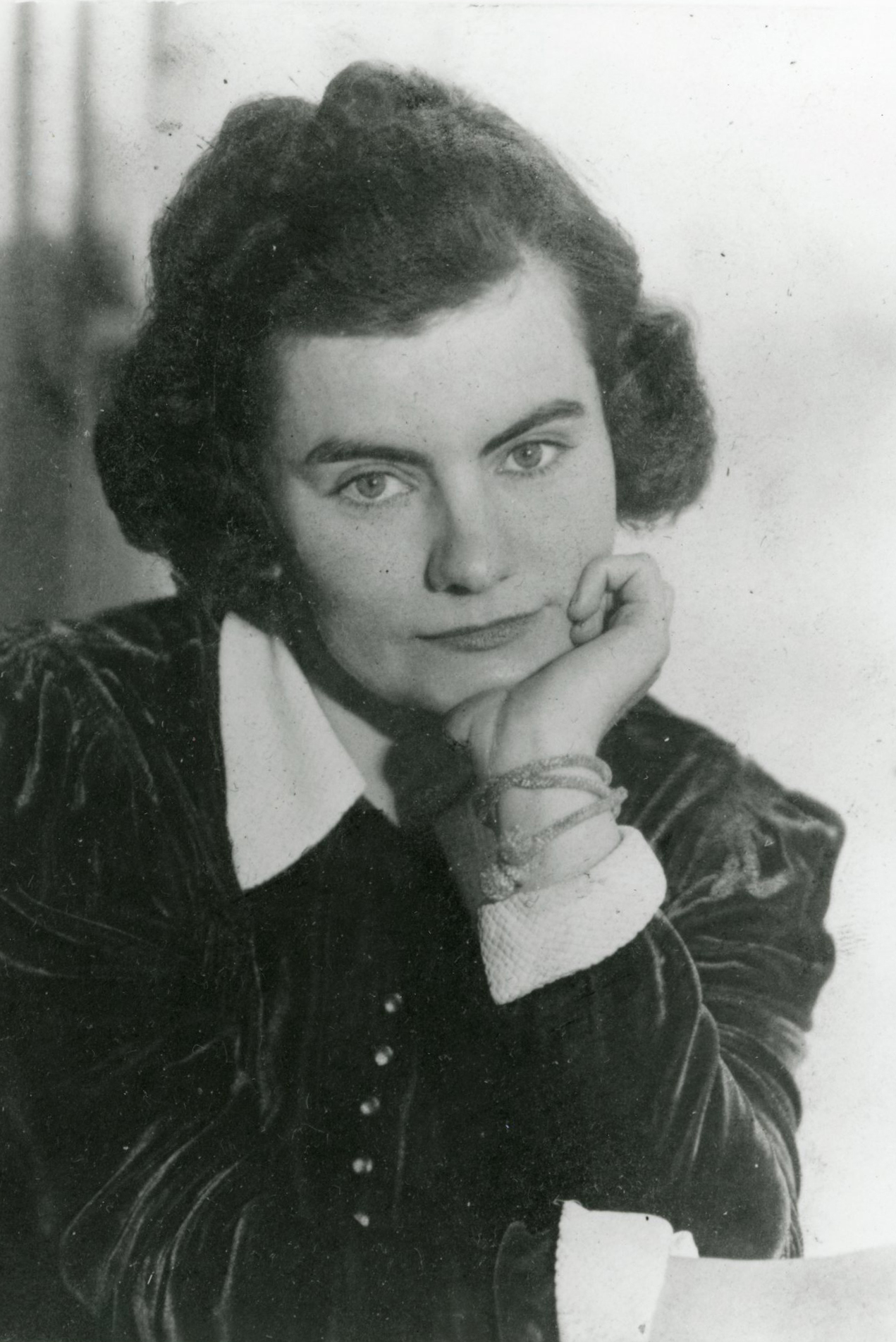

![]()

Ed Boyce, 1903.

Courtesy American Labor Union Journal 1.37 (June 18, 1903): 2 -

![A section of the longer column on Boyce identifying him as a "foul-mouthed blatherskite."]()

"Verification of Crime," Portland Oregonian, February 13, 1900.

A section of the longer column on Boyce identifying him as a "foul-mouthed blatherskite." Courtesy Portland Oregonian

-

![]()

Ed Boyce's obituary appeared on the front page of the Oregonian, December 25, 1941.

Courtesy Portland Oregonian

-

![]()

-

![]()

-

![]()

-

![]()

The Portland Hotel in about 1910.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb008496

Documents

Related Entries

-

![Chromite mining]()

Chromite mining

Chromite is a mineral that contains chromium. It is considered a strate…

-

![Francis J. Murnane (1914–1968)]()

Francis J. Murnane (1914–1968)

Francis J. Murnane was a longshoreman, labor leader, writer, and preser…

-

![Frank T. Johns (1889-1928)]()

Frank T. Johns (1889-1928)

Frank T. Johns of Portland was the Socialist Labor Party (SLP) presiden…

-

![Julia Ruuttila (1907-1991)]()

Julia Ruuttila (1907-1991)

Julia Ruuttila was a labor and investigative journalist, a poet and fic…

-

![Portland Hotel]()

Portland Hotel

The Portland Hotel (originally called the Hotel Portland), a project in…

-

![Socialism in Oregon]()

Socialism in Oregon

When Postmaster General James Farley jokingly toasted the " Soviet of W…

-

![West coast waterfront strike of 1934]()

West coast waterfront strike of 1934

"The most devastating work stoppage in Oregon's history" lasted 82 days…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Lukas, J. Anthony. Big Trouble: A Murder in a Small Western Town Sets Off a Struggle for the Soul of America. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1998.

Henry, Robert William. Ed Boyce: The Curious Evolution of an American Radical. MA Thesis, University of Montana, 1993.

"Notification of Crime: An ex-convict Fills His Magazine with Eulogy of Criminals and Abuse of Decent Men." Portland Oregonian, February 13, 1900.

"Death Claims Edward Boyce." Portland Oregonian, December 25, 1941.