When Postmaster General James Farley jokingly toasted the " Soviet of Washington" in 1936, he included Oregon among the remaining "47 states" for good reason: the influence of socialism on Oregon politics was marginal. But in the State of Washington, Farley ranted, the Democratic Party had adopted a platform that the Communist Party welcomed as the "first United Front" in North America. Washingtonians had elected leftists to the legislature and Congress, provided widespread public power to the people, supported a populist pension movement, and pioneered cooperative health care. Oregon did not follow Washington’s lead. While its northern neighbor approved public utility districts by popular vote in 1930, for example, Oregon did not allow such “socialistic” innovations until 1978.

But what is socialism? Most practicing socialists define classical or traditional socialism as an approach to economic organization based on public ownership of the major sectors—the “commanding heights”— of a planned, not a “free,” economy. In a socialist system, capital investment decisions are made through a public political process based on human and environmental priorities. Karl Marx and others offered socialism as an alternative to capitalism, a system based on private ownership of the means of production. In a capitalist system, investment decisions are made by private owners based largely on the expected effect on their profits.

The ideology of classical socialism similarly offers alternatives to capitalist values. Its adherents believe that equality and peace among humans and with nature require that human relations are based on cooperation rather than the competition and individualism that is rewarded under capitalism. Socialist ideology considers human history to be the history of class conflict, which in the capitalist era means that the interests of owners of the means of production are fundamentally opposed to the interests of those they employ.

While there have been movements in Oregon dedicated to replacing capitalism with classical socialism, its main influence on Oregon history has come from components of a socialist economy and ideology rather than a complete vision of socialism. This essay will treat classical socialism separately from the history of movements based on some of those components.

In Oregon, the early Socialist, Socialist Labor, and Communist Parties were exponents of the standard Marxist version of socialism in the twentieth century. None have measurable influence on the politics or economy of the state in the twenty-first century.

Classical Socialism in Oregon

The doctrinaire Socialist Labor Party, founded in 1897 and led by Marxist Daniel DeLeon, a professor at Columbia University, was the first socialist party in Oregon. The party insisted on a disciplined organization that would lead a revolutionary working class to overthrow capitalism. Its lively Astoria meeting hall at 1796 Exchange Street was preserved as a museum after its final meeting in the 1950s and until recently, when the last of them died, a group of elderly members met monthly at Portland's Central Library to protest the distortions of socialism rampant around them.

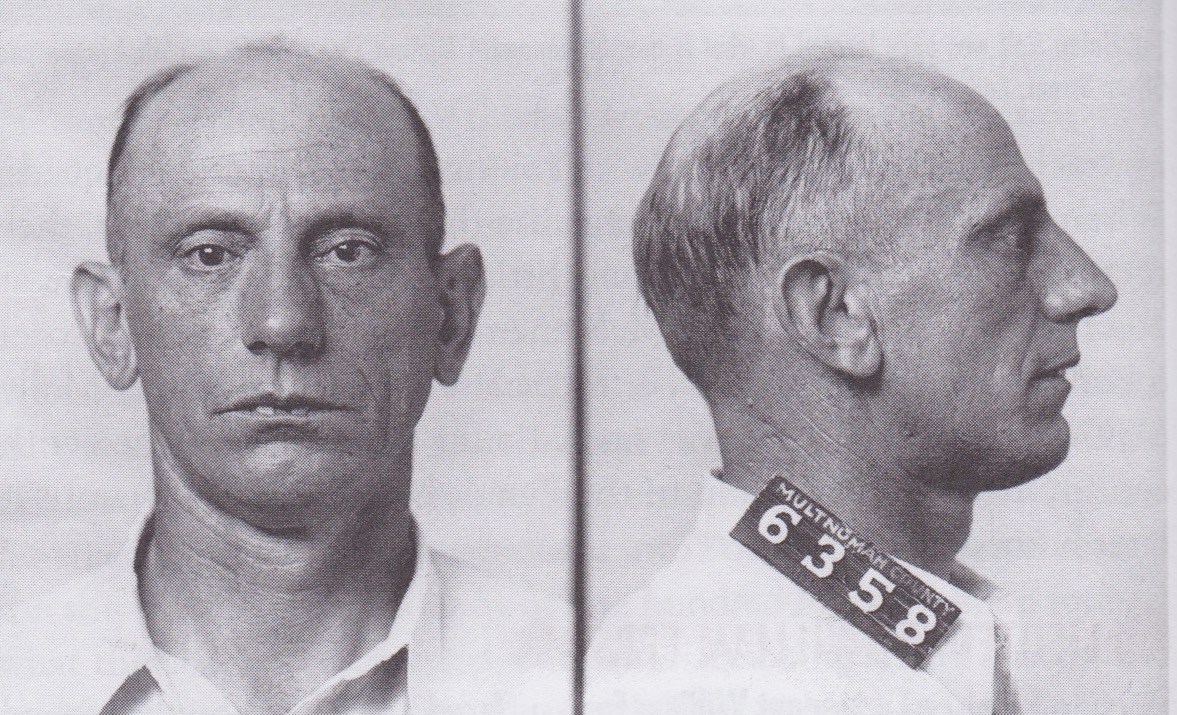

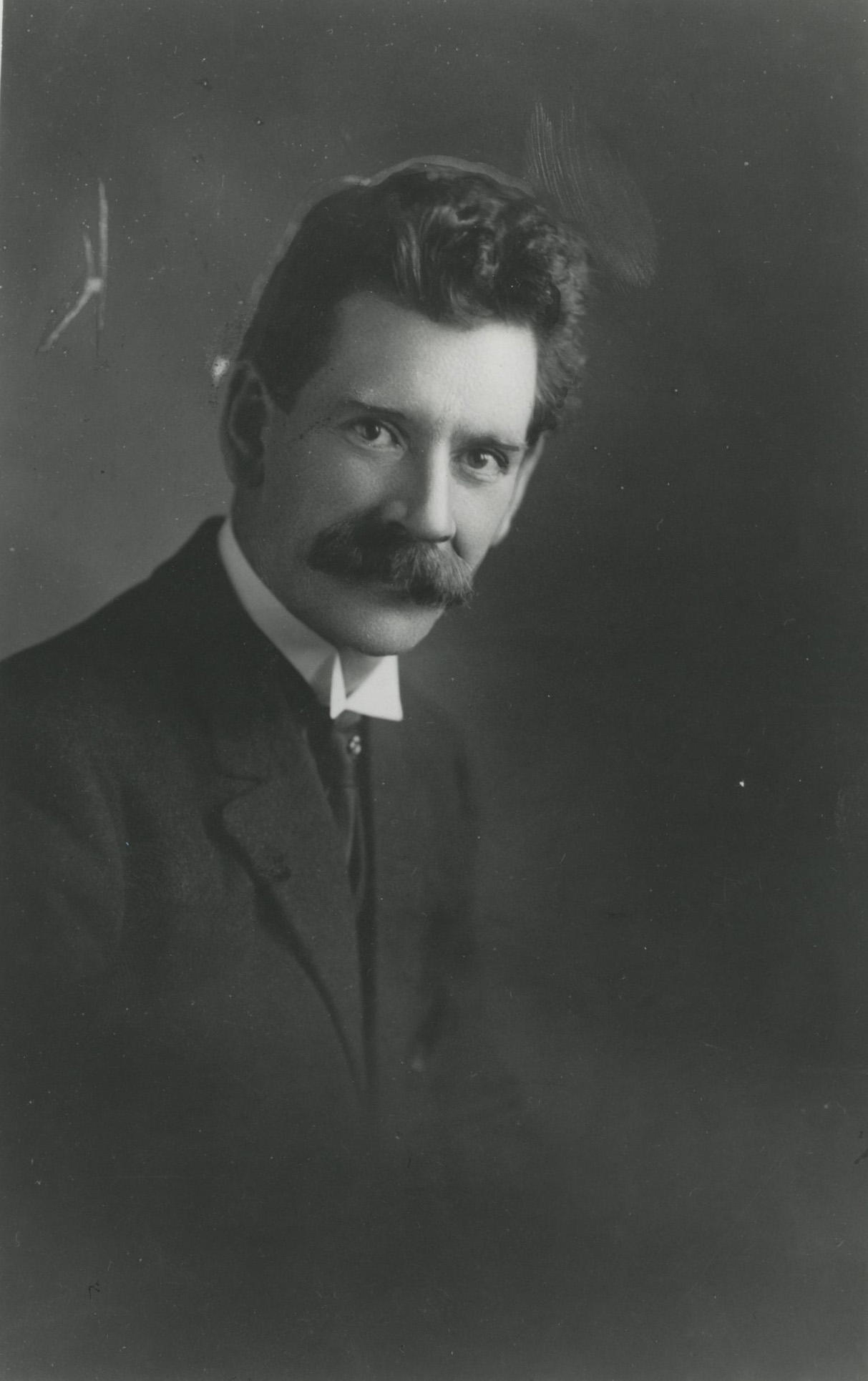

It was through the less doctrinaire but equally militant and uncompromising Socialist Party, led by Eugene Debs beginning in 1901, that classical socialism attained its greatest influence and electoral success in Oregon. Inspired by the Russian Revolution in 1917, two classical socialist organizations appeared in Oregon. The short-lived Portland Council of Workers, Soldiers and Sailors was established by Harry Wicks, a Socialist Party editor. At one of its meetings, the Portland police arrested fifty-six people under the Oregon legislature’s 1919 anti-syndicalism law. Soon after, they arrested six members of the new Communist Labor Party of America, which Portlander John Reed helped found in 1919. Wicks became a Communist Party activist and in 1936 accompanied its vice presidential candidate, James W. Ford, to Portland. Ford was the first African American to appear on a presidential ticket in the United States.

The Communist Labor Party soon became the Communist Party USA. After the suppression of radical political groups in the country during the Red Scare, in the wake of the Russian Revolution and the end of World War I, by the 1930s communists were taking a major role in organizing Oregon workers, including the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) and the International Woodworkers of America (IWA). Although committed to classical socialism, the Communist Party strategy was to prepare the ground for revolution by building working-class unions and promoting racial equality. The party’s opposition to fascism prompted eleven Oregonians to fight for the Spanish Republic in the Spanish Civil War during the 1930s. One of them, William Miller of Dayton, was killed in one of the last battles of the Lincoln Brigade.

Communist leaders in Oregon during the late 1930s until 1948 include Lincoln Brigade veterans Harold Spring, Carl Syvanen, and Earl Payne, as well as Dirk De Jonge, Harry Pilcher, Mark Haller, and Oscar Ruuttila from Astoria's "Red Finn" community. Some of those men and their followers participated in the Oregon Commonwealth Federation, an organization intended to bring liberals and radicals together to remake the state’s conservative Democratic Party.

Oregon communists and socialists participated enthusiastically in New Deal cultural programs, hoping that the public support of art for the people would express socialist visions. Among them were painters Martina Gangle and Albert and Arthur Runquist, who created murals in Oregon schools and at the University of Oregon, and Ray Neufer, a WPA carpenter who built the armchair for President Roosevelt’s visit to Timberline Lodge in 1937. Oregon established WPA “people’s” art centers in Portland, Gold Beach, Salem, and La Grande, and Portland hosted WPA theater and musical groups whose performances included works by socialist playwrights and composers.

The last significant revival of a socialist-friendly, liberal-labor coalition during the New Deal was the Progressive Party's 1948 campaign, when Peggy Carlson, the widow of Marine General Evans Carlson, ran as the party’s candidate for Oregon’s Second Congressional District. That year, Progressive Party candidates included Estus Curry, an African American community leader in Vanport, and labor leader Francis Murnane, who the Democratic Party nominated for the legislature. All were defeated in the general election, as their former liberal allies capitulated to McCarthyism and denounced them as enemies, including Monroe Sweetland, who had once been a socialist. CIO unions with millions of members were expelled following the 1948 CIO convention held in the Masonic Temple in Portland (now part of the Portland Art Museum).

Oregon Movements Incorporating Socialist Values

Socialist values of cooperation and common ownership were fundamental to the founding of late nineteenth-century utopian agricultural communities, which rejected industrialization and urbanization. In Oregon were Aurora Colony (1878), New Odessa (1886), Nehalem Valley Cooperative (1886), Socialist Valley (1895) in Linn County, and Bellamy (1897). Karl Marx was honored by an Oregon Coast post office at present-day Neskowin in 1904-1907 and the Carl Marx barber shop, which operated on Portland's east side during the early 1930s. Socialist values also inspired some of Oregon's populist agrarian, anti-imperialist, anti-racist, and working-class movements. They were invoked in Portland's first recorded protest by African Americans in 1898, when the local Afro-American League held a meeting to denounce the violent white racist insurrection against the elected city government of Wilmington, North Carolina, when a mob of white men forced the resignation of Black city officials.

The earliest March on Washington was led by the 5th Regiment of Coxey's army, which set off from 3rd and Burnside in 1894 and commandeered a train at Troutdale to join Jacob Coxey’s "Industrial Army" in Washington to demand work. Coxey organized on the socialist principle that public money should be used to provide work for the victims of capitalist episodes of boom and bust, but the movement did not envision a socialist future. His "army" expressed a militant but modest demand that Congress authorize money for road construction as an employment program.

The Industrial Workers of the World, basing its appeal on the traditional socialist principle of class war, organized workers in Oregon's timber, mining, and fishing industries to take power from the “bosses.” The IWW rejected electoral politics in favor of direct action—that is, strikes, sabotage, and mass demonstrations. The Wobblies, as they were called, wanted the establishment of One Big Union to unify the working class and replace capitalism through a general strike by all workers of the world. Rather than establishing a traditional socialist state, however, the IWW believed that workers should control the means of production. Together with the Socialist Party, whose presidential candidate received 6 percent of the vote while jailed during the 1920 election campaign, the IWW considered World War I an "imperialist war." Because of its militant opposition to the war, Wobblies were prosecuted and imprisoned under Oregon's criminal syndicalism law. In Florence, Oregon, local vigilantes kidnapped seven Wobblies and forced them and other foreign-born radicals to leave town. Joe Hill, a member of a Portland local who was later executed in Utah, introduced his song "The Preacher and the Slave" at the Portland IWW hall.

The IWW was among the first radical organizations in Oregon to welcome women as leaders, including labor activist Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and physician Marie Equi, who lived together in Equi’s home in Portland during the 1920s. Equi was convicted and jailed for sedition in 1918, after she delivered several anti-war speeches. Flynn later became a national leader of the Communist Party, for which she was imprisoned from 1955 to 1957 under the Smith Act for "advocating the violent overthrow of the US government."

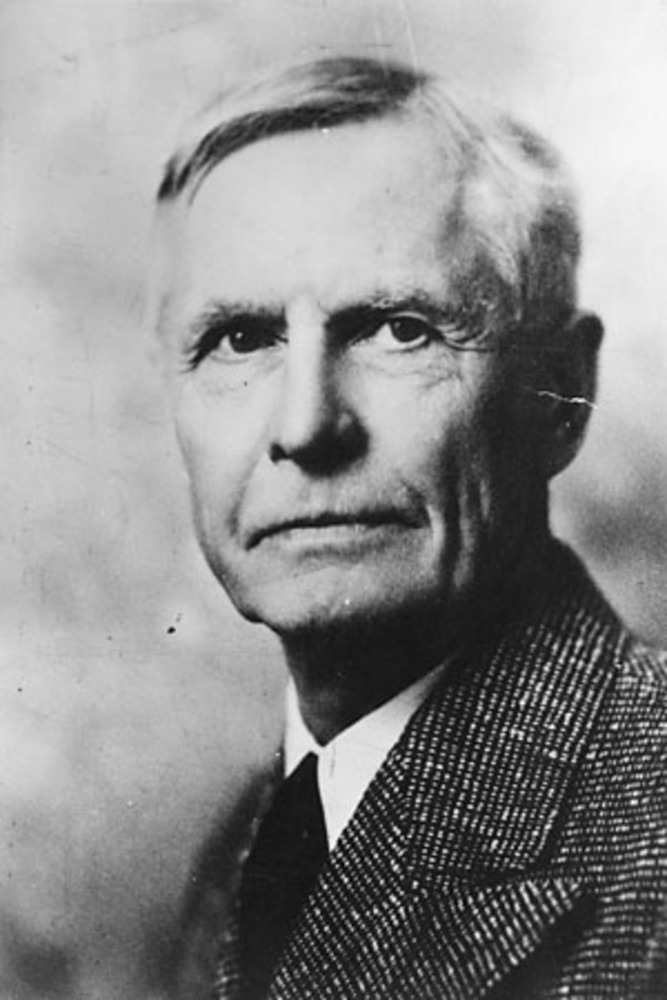

The Populist Party led class-based opposition to so-called eastern monopolists. In 1896, Populist candidates received the support of 48 percent of Oregon voters, all men, almost as many as presidential candidate William McKinley. President McKinley’s invasion of the Philippines in 1898 led to the formation of the Anti-Imperialist League, led by populist William Jennings Bryan. To protest the invasion, C.E.S. Wood, the most prominent dissident of Portland's elite class, declared: "If I were a Filipino, I would fight, fight, fight until the sun was blocked from my eyes." Portland was one of the eight most influential of the League's one hundred branches in 1899.

In 1932, members of the so-called Bonus Army gathered in Washington, D.C., to demand that Congress honor pensions promised World War I veterans. Their national commander was Sergeant Walter Waters of Burns, Oregon. Waters was not a socialist of any variety, but communist and socialist veterans participated in the march, which prompted the U.S. Army to attack the marchers’ camp at Anacostia Flats. General Douglas MacArthur and Major Dwight Eisenhower led troops in burning down the Bonus Marchers’ encampment.

By the 1930s, the successor to Eugene Deb's Socialist Party was minister and pacifist Norman Thomas. Under his leadership, the party replaced Deb's commitment to a working-class victory over capitalism with an emphasis on mitigating its most extreme ”excesses.” One of Thomas’s supporters was Tom Burns, who ran a clock shop and radical library on Skid Road (West Burnside) in Portland and was known as the "most arrested man" in Portland for his soapbox rants against the local elite.

Over the next decades, membership in the Socialist Party declined. Then, in 2016, presidential candidate Bernie Sanders won the Oregon Democratic primary as a Democratic Socialist. Local chapters of the Democratic Socialists of America were re-energized, and local groups are now active in Corvallis, Bend, Salem, Eugene, and Portland.

-

![]()

Finnish Socialist Club, Astoria, 1922.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi26734

-

![]()

An early issue of the Spirit of the Times, an IWW publication.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Pam331 886142i

-

![]()

IWW poster.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi77728

-

![]()

IWW strike committee, Astoria, 1948.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 85067

Related Entries

-

![Bonus Army]()

Bonus Army

In 1932, with the Northwest lumber industry hit especially hard by the …

-

![C.E.S. Wood (1852-1944)]()

C.E.S. Wood (1852-1944)

C.E.S. Wood may have been the most influential cultural figure in Portl…

-

![Coxey's Army]()

Coxey's Army

One of the periodic economic collapses endemic in America’s economic hi…

-

![Criminal Syndicalism Law of Oregon]()

Criminal Syndicalism Law of Oregon

Oregonians were light-headed from days of celebrating the end of World …

-

![Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)]()

Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW or "Wobblies"), founded in 190…

-

![John "Jack" Reed (1887-1920)]()

John "Jack" Reed (1887-1920)

Almost ninety years after his burial on Red Square in Moscow, John Sila…

-

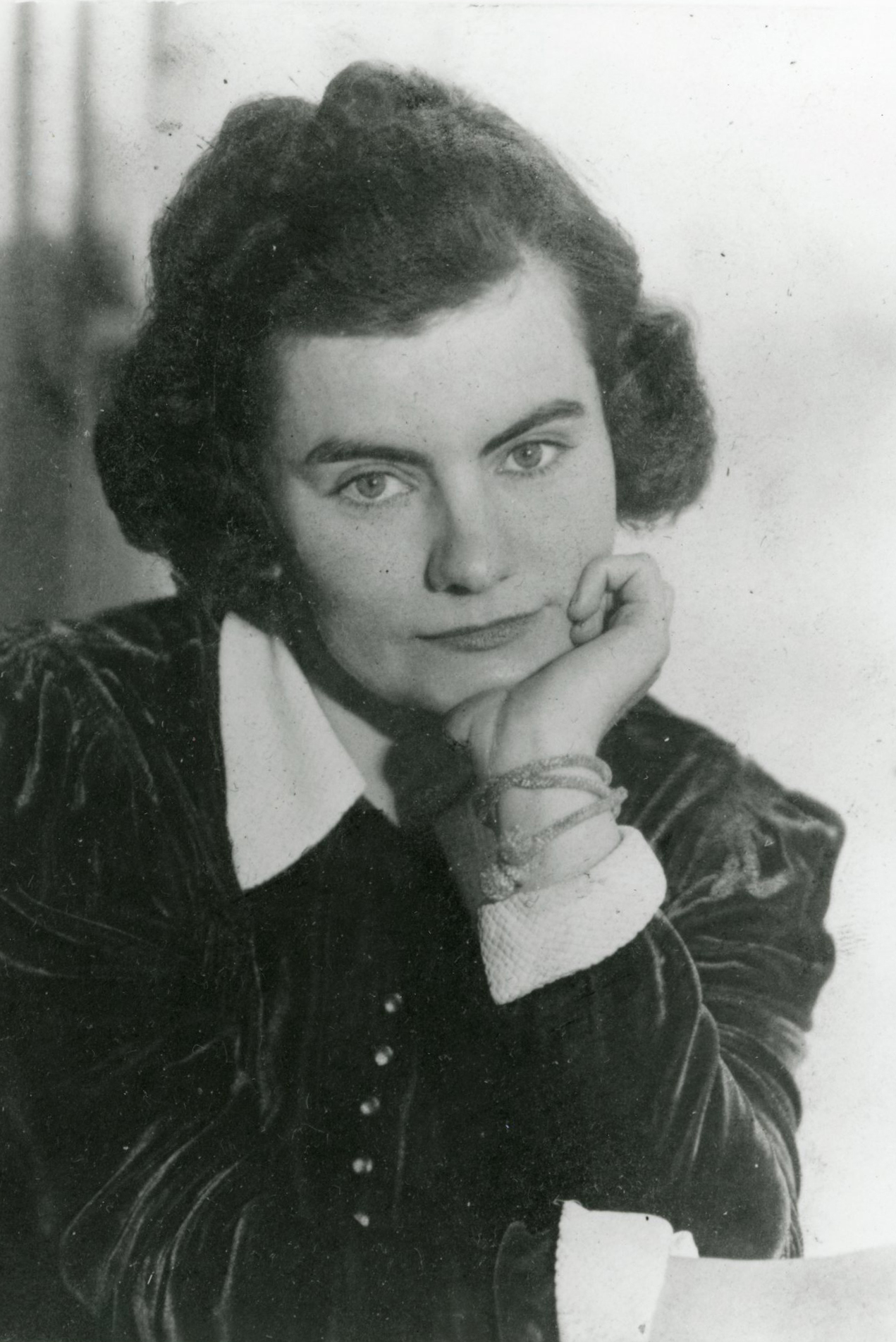

![Julia Ruuttila (1907-1991)]()

Julia Ruuttila (1907-1991)

Julia Ruuttila was a labor and investigative journalist, a poet and fic…

-

Marie Equi (1872-1952)

Dr. Marie Equi was a fiercely independent Oregon physician who was enga…

-

![Martina Gangle Curl (1906 - 1994)]()

Martina Gangle Curl (1906 - 1994)

Martina Gangle Curl was a painter, printmaker, and woodcarver who creat…

-

![McCarthy Era (late 1940s-late 1950s)]()

McCarthy Era (late 1940s-late 1950s)

As Woody Guthrie observed at the dawn of the McCarthy Era in 1947, "Por…

-

![Monroe Sweetland (1910-2006)]()

Monroe Sweetland (1910-2006)

Monroe Sweetland's life embraced the cultural revolution of the 1920s, …

-

![Oregon Commonwealth Federation]()

Oregon Commonwealth Federation

Following the inaugural meeting of the Oregon Commonwealth Federation (…

-

![Populism in Oregon]()

Populism in Oregon

Populism refers to a political discourse that defines the interests of …

-

![Socialist Party of Oregon]()

Socialist Party of Oregon

The Socialist Party of Oregon was founded in 1901, at the same time as …

-

![Thomas Joseph Burns (1876-1957)]()

Thomas Joseph Burns (1876-1957)

In his fifty-two years in Oregon, Tom Burns threw himself into nearly e…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Johnson, Robert D. The Radical Middle Class: Populist Democracy and the Question of Capitalism in Progressive Era Portland, Oregon. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006.

Kopp, James J. Eden within Eden: Oregon’s Utopian Heritage. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2009.

Lepore, Jill. “Eugene V. Debs and the Endurance of Socialism.” New Yorker, February 11, 2019.

Munk, Michael. The Portland Red Guide: Sites and Stories of our Radical Past. 2d ed. Portland: Ooligan Press, 2011.

Murrell, Gary. Iron Pants: Oregon's Anti-New Deal Governor, Charles Henry Martin. Pullman: Washington State University Press, 2000.