The Portland Hotel (originally called the Hotel Portland), a project initiated by Henry Villard and the Northern Pacific Railroad, was designed in 1882-1883 and constructed in 1888-1890. The hotel established a new standard in elegance for accommodations in Portland and introduced patrons and local architects to the latest architectural trends in New York and Boston.

When Villard assumed control of the still-incomplete Northern Pacific in 1879, he set high standards for the projected buildings connected to the railroad. He commissioned architects McKim, Mead & White of New York City to design a large, upscale hotel to accommodate guests arriving after long trips on the transcontinental trains. The hotel would stand on the block immediately west of the Pioneer Courthouse and the post office. Unable to persuade Portland's business leaders to form a company to build the hotel, Villard initiated it as a project of the Northern Pacific Railroad.

Work began on the Portland Hotel in 1883-1884, and Charles F. McKim, William R. Mead, and McKim’s office assistant William M. Whidden made several trips to Portland to check on construction. (Some have claimed that Stanford White was involved, but the firm's business records make it clear that he was not). In 1884, however, Villard was forced to resign the presidency of the Northern Pacific, and all the architectural projects connected with the railroad, including the hotel, were halted.

The unfinished walls became a refuge for transients and muggers, and Portland civic leaders and businessmen formed a syndicate in 1888 to finish building the hotel. By this time, McKim, Mead & White were too busy to take on the job, so the Portland sponsors got in touch with William Whidden, who had worked on the original designs. Whidden persuaded his friend, Ion Lewis from Boston, to join him in a partnership in Portland. They completed the hotel in 1888-1890, making only minor changes to the original design.

With an H-shaped plan and 326 guest rooms, the Portland Hotel was electrically illuminated throughout. It rose six stories to high-hipped roofs dotted with dormers. Particularly distinctive were the towers nestled in the corners of the recessed entrance court. Above the lower walls of rough, dark, basalt masonry blocks, the upper brick walls were surfaced with picturesque pebble-dash stucco, with window openings and other trim outlined in cut brick and terra cotta, the same materials later used by Van Brunt & Howe for Union Station (1893-1896).

The Portland Hotel was decidedly different from other contemporaneous buildings in Portland. Described by the Oregonian in 1890 as “the finest, largest and best” hotel in the Pacific Northwest, it became the preferred location for presidents, politicians, business leaders, and celebrated social figures. For several generations, the hotel was “the center piece of the city’s upper- and upper-middle-class social life.” Its scale of operation and costly construction initially had made it unprofitable for investors, but its grandeur and superb dining rooms made it a center of social events for many years.

With subsequent new buildings designed by Whidden & Lewis, including City Hall and the Portland Public Library (destroyed just after 1911), Portland architecture changed, passing from the awkward roughness of a frontier town to the stylistic maturity of an urban metropolis. The twenty-year time lag between architectural developments in the East and Portland disappeared. Marion Dean Ross, an architectural historian at the University of Oregon (1947-1978) described Portland architecture, after the impact of McKim, Mead & White and their protégés Whidden & Lewis, as moving from “an interesting provincial and vernacular character to a more studied correctness.”

After 1913, the Portland Hotel was outstripped in elegance by the new Multnomah and Benson Hotels. By the mid 1940s, the fading doyen fell on hard times. Meier & Frank bought the building in late 1944, and it was demolished in 1951 for parking space. Nevertheless, the urban centrality of the building site continued to assert itself, and by the early 1970s plans were underway to transform the site into Portland’s "public living room," Pioneer Courthouse Square, a project realized from designs by Willard Martin in 1981-1984. The brick paving of the plaza recalls the brick of the hotel, and on the northeast corner of the plaza are some of the wrought-iron decorative fence panels that defined the Portland Hotel’s grand entry court.

-

![]()

The Portland Hotel.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib. OrHi11935

-

![]()

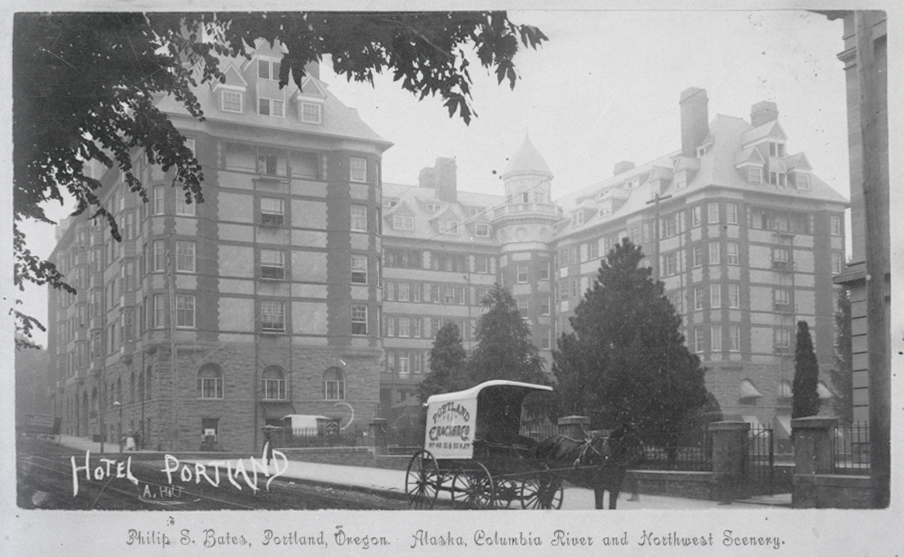

The Portland Hotel (photo by Philip S. Bates).

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib. OrHi11104

-

![]()

The Portland Hotel in about 1910.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb008496

-

![]()

The Portland Hotel in the 1930s (photo by Walter Boychuk).

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb008481

-

![]()

The Portland Hotel in about 1895.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib. OrHi51412

-

![]()

A postcard of the Portland Hotel in about 1900.

Courtesy Lipschuetz and Katz

Related Entries

-

![Henry Villard (1835-1900)]()

Henry Villard (1835-1900)

Henry Villard gained national significance as a journalist, advocate of…

-

![Pioneer Courthouse Square]()

Pioneer Courthouse Square

In the heart of downtown Portland, Pioneer Courthouse Square fulfills i…

-

![Whidden and Lewis, architects]()

Whidden and Lewis, architects

From 1890 to 1910, the Whidden and Lewis firm dominated architectural d…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Gohs, Carl. "There Stood the Portland Hotel." The Sunday Oregonian Northwest Magazine, May 25, 1975, 8-11.

Nicoll, G. Douglas. “Stanford White and the Portland Hotel: A Case Study in Historical Mutation.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 99:3 (Fall 1998), 336-345.

Nicoll, G. Douglas. “The Rise and Fall of the Portland Hotel.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 99:3 (Fall 1998), 298-331.

Roth, Leland M. McKim, Mead & White, Architects. New York: Harper & Row, 1983.

Villard, Henry. Memoirs of Henry Villard: Journalist and Financier, 1835-1900. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co., 1904.