Thomas Dryer, the first editor of the Oregonian, named the Salem Clique, whom he described in the Oregonian on March 13, 1852, as “political hacks and BAR-ROOM BRAWLERS—who have disgraced themselves, the territory, and the people by their miserable policy.” Historians largely adopted Dryer’s judgment, and their accounts of Oregon territorial politics during the 1850s recognize the influential role of the Clique, often judging that role to be detrimental, if not criminal.

The Clique

The Salem Clique was made up of a group of young men who, attracted by the prospect of farmland and prosperity, emigrated to the Oregon Territory in the late 1840s and early 1850s. In Oregon, they found a semi-colonial governmental structure, where voters—that is, white men—elected territorial legislators and the United States president made executive and judicial appointments. The one territory-wide position that voters chose was delegate to Congress, who represented the territory’s interests but had no voting privileges—similar to today’s lobbyists.

The delegate in 1850 was Samuel Thurston, an ambitious Democrat whose concerns about his political future were agitated by local efforts to organize the Whig Party and the plan for a Whig newspaper in Portland. Determined to have a Democratic newspaper in Oregon City, the territorial capital, Thurston recruited Asahel Bush, a twenty-six-year-old Democrat with newspaper experience who agreed to move to Oregon and establish a newspaper to be named, at Thurston’s insistence, the Oregon Statesman. Thurston also charged him with organizing the Democratic Party in the territory. Bush arrived in Oregon City in September 1850, and the Statesman published its first issue on March 28, 1851.

Bush soon met the men who would form the Salem Clique. Matthew Deady had arrived in Oregon Territory in 1849, having studied law and passed the Ohio Bar. He was elected in 1850 to the territorial assembly, where as a member of the Judiciary Committee he codified the territory’s laws. He got Bush elected clerk of the assembly and then public printer. James Nesmith emigrated to Oregon in 1843 as part of the Great Migration. He studied law, passed the bar, and in 1845 became a judge for the Provisional Government. In 1849, his success in the California gold fields made him a wealthy man, and he returned to Oregon and settled in Polk County. Lafayette Grover, like Bush, had been recruited to Oregon by Thurston. He settled in southern Oregon, where he was clerk of the U.S. District Court. Also in Bush’s orbit was Reuben Boise, whom he had known in Massachusetts when he studied law with Boise’s uncle. Boise had a farm in Polk County and opened a law office in Salem.

Others who joined Bush’s circle included George Curry, Benjamin Harding, Delazon Smith, Fred Waymire, Orville Pratt, and Stephen Chadwick. Each was a Democrat with an interest in politics. Coming together in the territorial capital, where several of these men were members of the assembly or the judiciary, they developed a symbiotic relationship with Bush and the Statesman: they funneled information to the editor, and he supported their policies and political aspirations.

Early Dilemma

Early in the Clique’s association, Bush faced a dilemma. Joseph Lane had been appointed territorial governor by President James Polk in 1848, although he had lost the position the next year when Zachary Taylor became president and replaced Lane with a Whig. Lane was popular and well-respected, and he caught Bush’s attention when he returned to Oregon in 1851. Talk soon surfaced that he was running for delegate.

Given his obligation to Thurston, Lane’s candidacy was a quandary for Bush, one that was resolved by Thurston’s death while traveling from Washington, D.C., to Oregon to campaign in the coming election. Bush quickly endorsed Lane for Oregon’s delegate and became his champion. Not all of the Clique supported Lane, however, and Deady was decidedly critical of him. Nevertheless, Lane won the election. The connection with Lane proved beneficial to the Clique, particularly when it came to government grants and appointments to government positions. Meanwhile, the Oregon Democratic Party organization began to take shape, with James Nesmith chosen as its chair. In 1852, at Deady’s urging, the territorial government moved the capital to Salem, a change expected to favor Democrats. Bush and the Statesman followed.

Oregon Becomes a State

As the territory moved toward statehood, a major question was whether Oregon would be a slave or a free state. The Provisional Government had already banned slavery and excluded Blacks from the territory, but the Clique was divided on the issue. Lane was an advocate of slavery, as were Matthew Deady, Delazon Smith, and Joe Lane. But Bush firmly opposed slavery in Oregon, although out of pragmatic rather than principled concerns. He advised: “The only real questions are, is the introduction of slavery into Oregon practicable? And will it prove profitable?” However it would be decided, Bush made one thing clear: “The people of Oregon are eminently National in their sentiments and attachments, and whether she enters the Union slave or free, she will be a conservative National State, and in every emergency will stand by the Union and the constitution as they are, with the compromises upon which they were formed and upon which they rest.”

It took four elections until Oregon Territory voters supported statehood and called for a constitutional convention. Meeting on August 17, 1857, forty-four of the sixty delegates were Democrats, including Deady, Chadwick, Grover, Smith, Boise, and Waymire. Members of the Salem Clique chaired six of the eleven standing committees, and Deady was elected president. Delegate Thomas Dryer, the Whig editor of the Oregonian, regularly wrote that the Clique had predetermined the provisions of the constitution. He compared them to Hannibal, Nero, Robespierre, Judas Iscariot, and Benedict Arnold, “but none of these have ever attempted a political tyranny equal to that of the Salem inquisitors, self-christened and self called ‘the democracy of Oregon.” In fact, the members of the Clique were not at all in agreement about what ought to be in the constitution, and the records of their debates document their many differences.

Eventually, the convention adopted Lafayette Grover’s suggestion that the questions of slavery and the admission of Blacks to Oregon would be left to voters. The delegates wrote one provision against slavery and one allowing it, and they composed one provision allowing Black immigrants and another excluding them. Bush wrote in the Statesman on October 16, 1857: “A Constitution is itself but a compromise. In its adoption by a convention, or its ratification by the people, a contrariety of sentiment is expected to exist...[but] the minority must yield to the views of the majority.” The Clique campaigned in favor of the constitution, which voters approved by a comfortable margin. Voters opposed slavery and the admission of Blacks by even greater margins.

When the petition for statehood reached Congress, the rejection of slavery in Oregon’s constitution triggered opposition from Southern lawmakers, fearful that admitting a free state to the Union would set a precedent and give Northern states more votes in the House and Senate. The Senate finally approved admission in May 1858, and the House followed in February 1859. Bush ascribed the delay to Lane’s intervention, claiming that he wanted to wait until he could be certain of a Senate seat. With that, their close relationship ended. At the same time, Deady had decided to support Lane, largely because of their shared position on slavery. Delazon Smith, the other Clique member most committed to slavery, also embraced Lane.

Party Politics and the Collapse of the Clique

The first Oregon legislature gathered in May 1859, with twelve Democrats, three Republicans, and one Independent in the Senate and twenty-nine Democrats and four Republicans in the House. The Clique’s influence was limited by divisions in the Democratic Party, divisions that reflected a resentment of the group’s power. The opposition, whom Bush labeled “Softs,” was led by A. L. Lovejoy and was, for the most part, from Portland.

Much to Bush’s dismay, the legislature chose Lane and Smith as Oregon’s first United States Senators. They would serve for only a year, until the 1860 election. Meanwhile, Lane’s connection with President James Buchanan gave him some control over presidential appointments and federal patronage in Oregon, what Bush called “a stupendous corruption fund, by means of which he hopes to control the democratic organization and keep himself in the United States Senate.”

The 1860 presidential campaign revealed the fracture in the national Democratic Party. Unable to agree on a candidate at its convention, Northern delegates nominated Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas; the Southern faction nominated John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky for president and Joseph Lane for vice-president. The election divided the Clique, with Bush strongly supporting Douglas and condemning Lane as “the tail of a treasonable ticket” and Deady declaring that he would vote for Breckinridge and Lane. In the June 26, 1860, Oregon Statesman, Bush was harsh in his evaluation of the Republican nominee, Abraham Lincoln: “As a stateman, Mr. Lincoln takes rank—nowhere....Of all the candidates who were before the Convention, there is not one who is not his superior in ability.”

Meeting in September, the Oregon legislature included an eighteen-member Douglas faction and a seventeen-member Breckinridge faction, which gave the thirteen Republicans the balance of power. The Douglas Democrats and the Republicans compromised to choose James Nesmith for one Senate seat and Republican Edward Dickinson Baker for the other. Both opposed slavery. Despite Bush’s opposition, nine Democratic newspapers endorsed Lane. Oregon was the only Northern state to favor Breckinridge over Douglas, while Lincoln got more votes than either. The Clique’s power had collapsed.

Lane announced his intention to “urge the democrats of Oregon to adopt the Constitution of the Confederate States as their platform.” Despite his efforts, Oregon remained in the Union, an outcome that journalist Leslie Scott later attributed to the influence of Asahel Bush and James Nesmith.

-

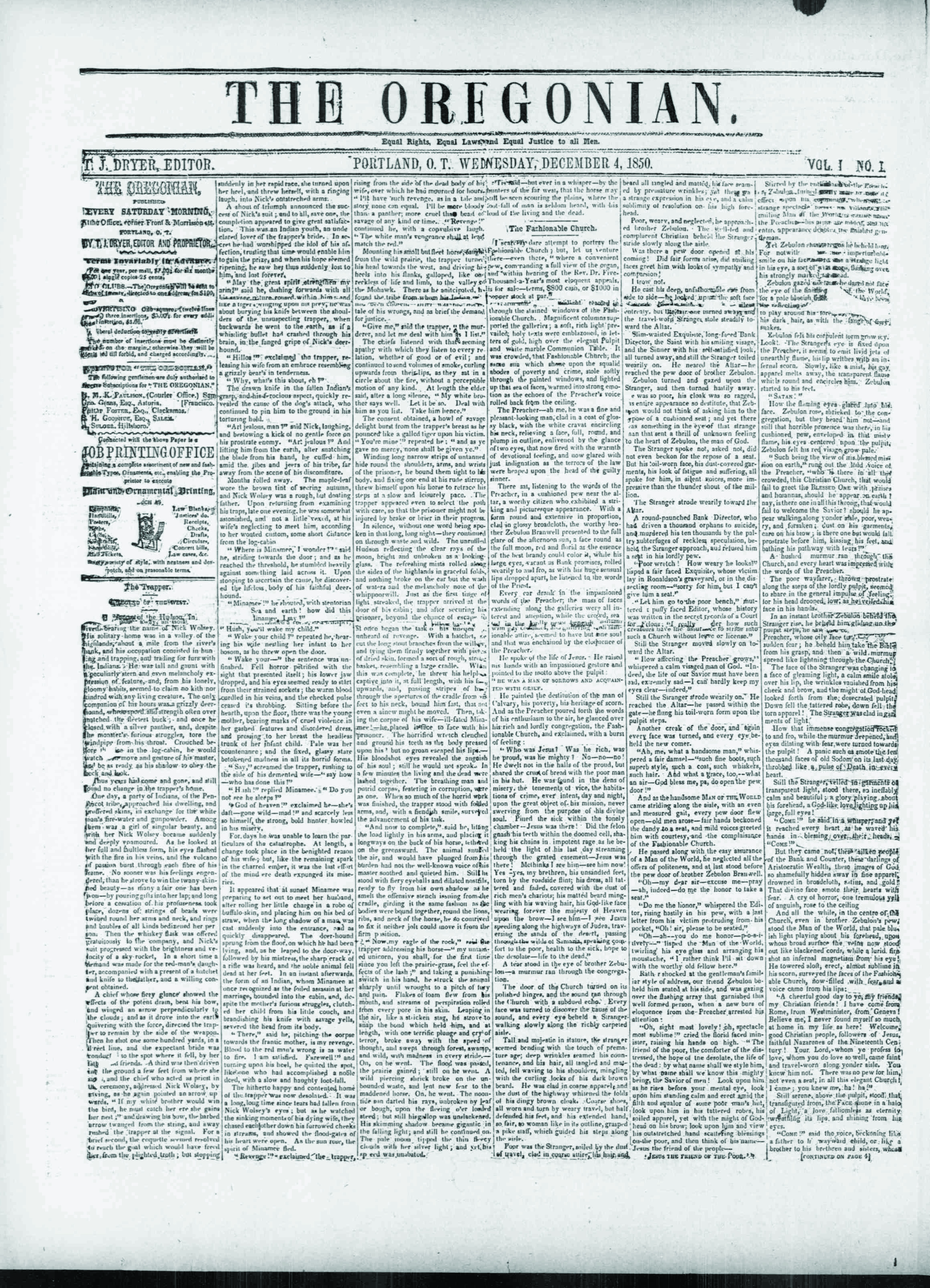

![]()

Samuel Thurston.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 020665

-

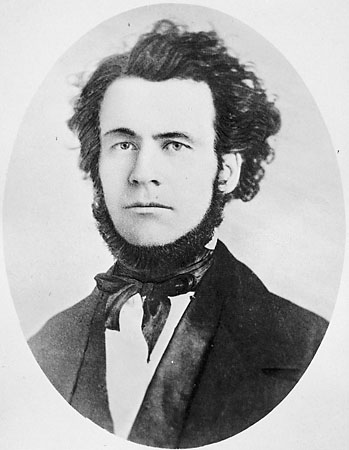

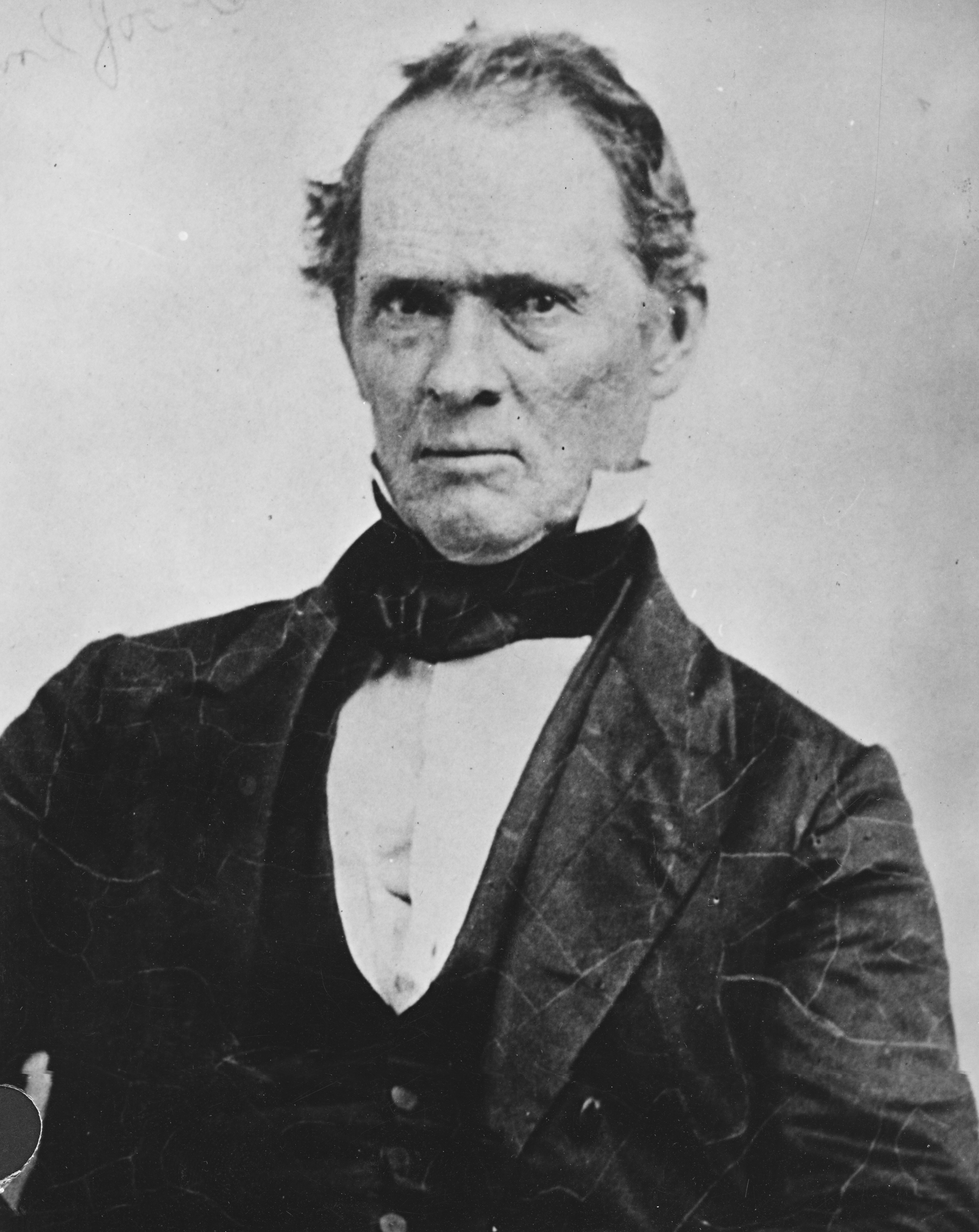

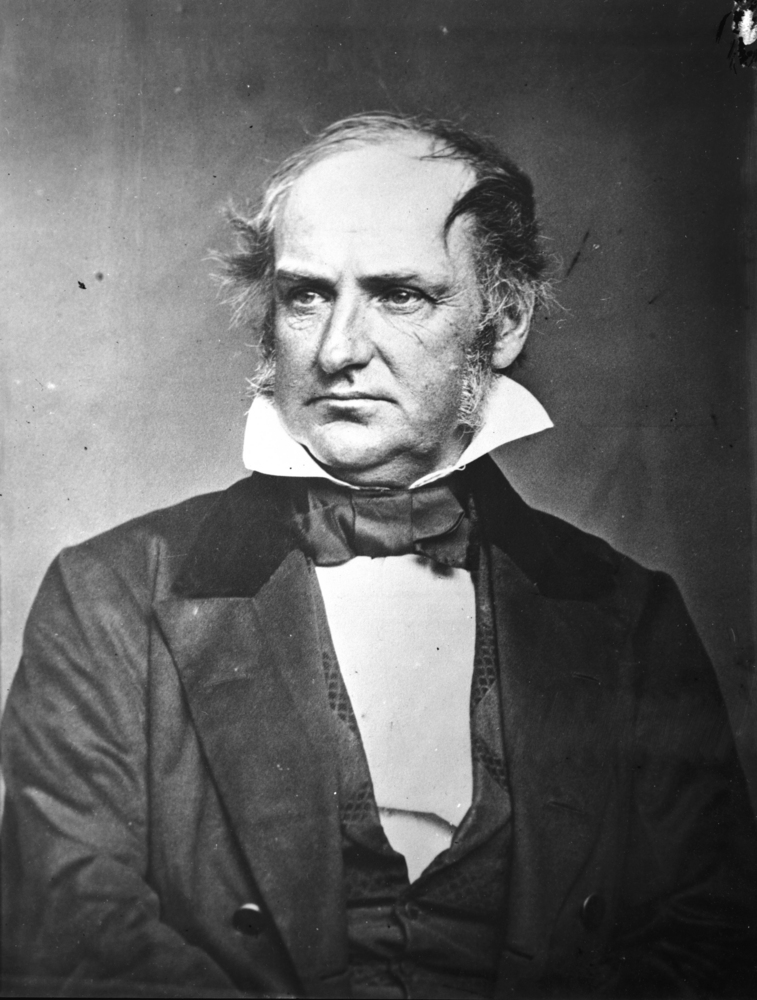

![Asahel Bush]()

Asahel Bush.

Asahel Bush Oregon Historical Society Research Library ba017992

-

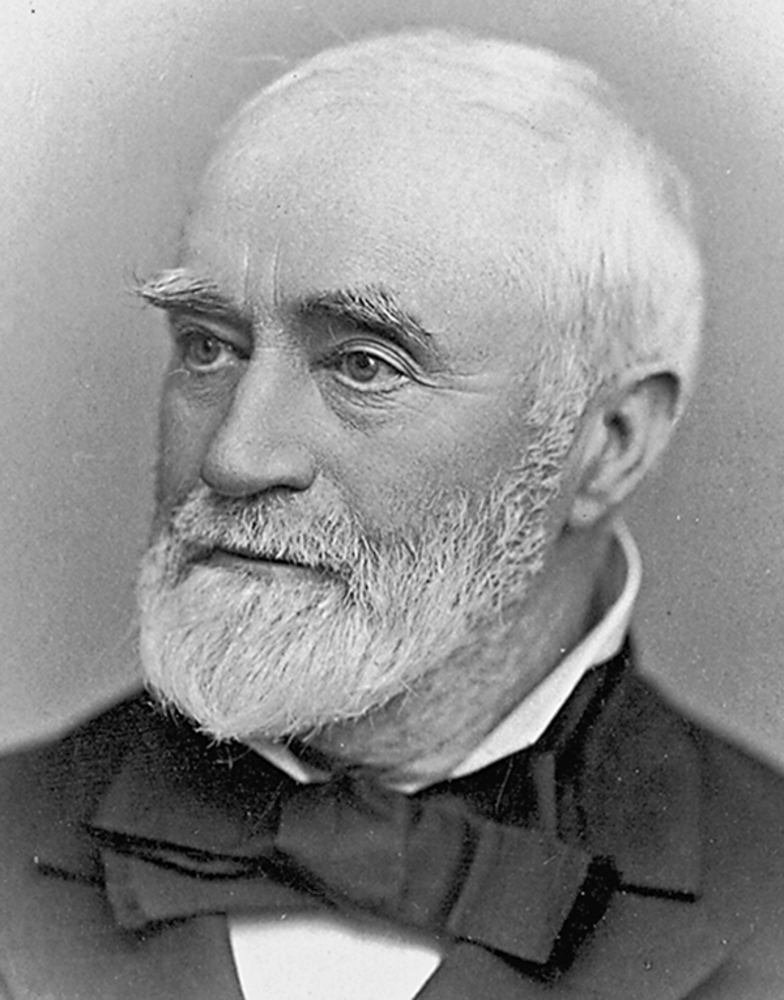

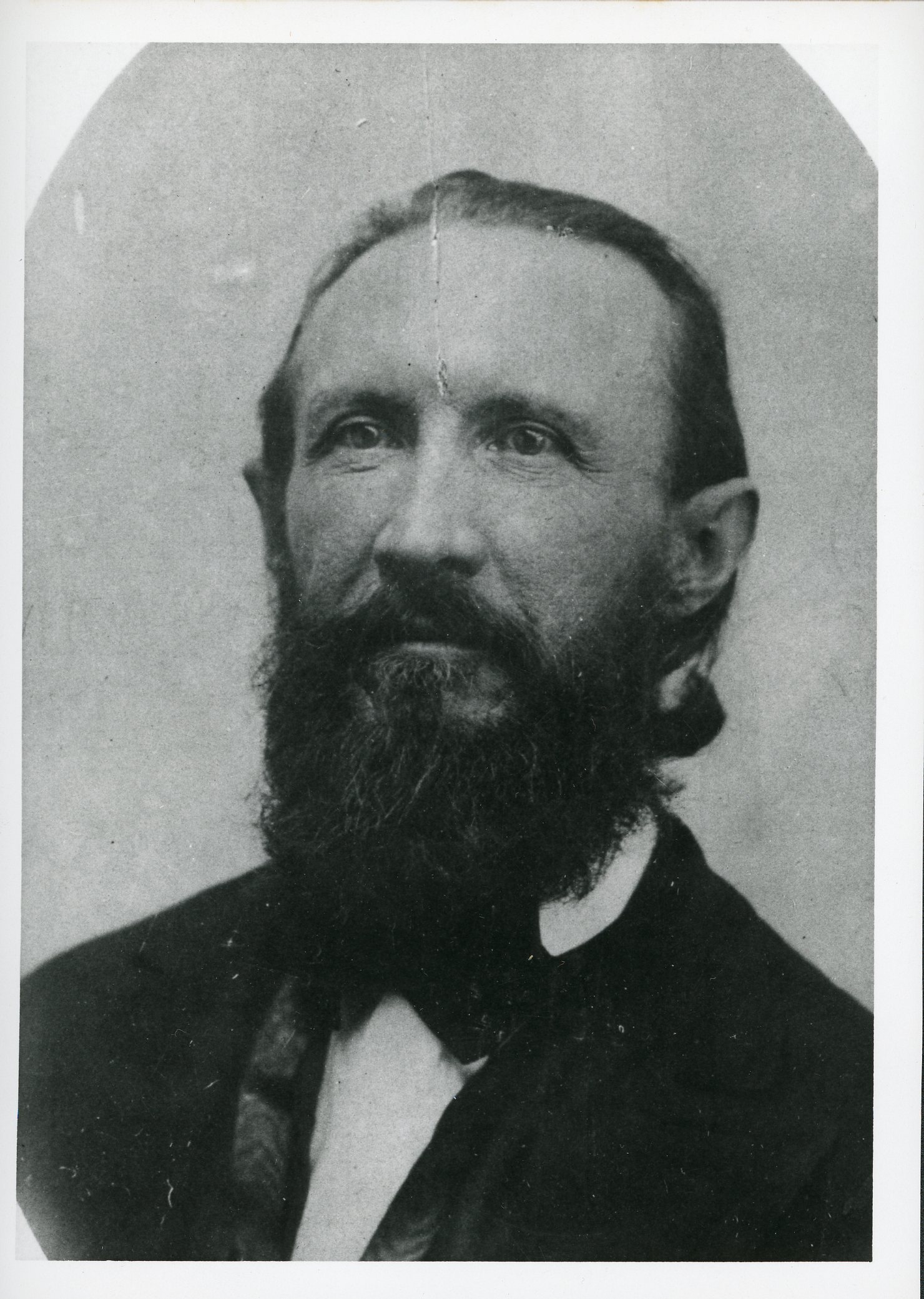

![Matthew P. Deady at age 35, about 1859.]()

Deady, Matthew P., OrHi 63119.

Matthew P. Deady at age 35, about 1859. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Libr., OrHi 63119

-

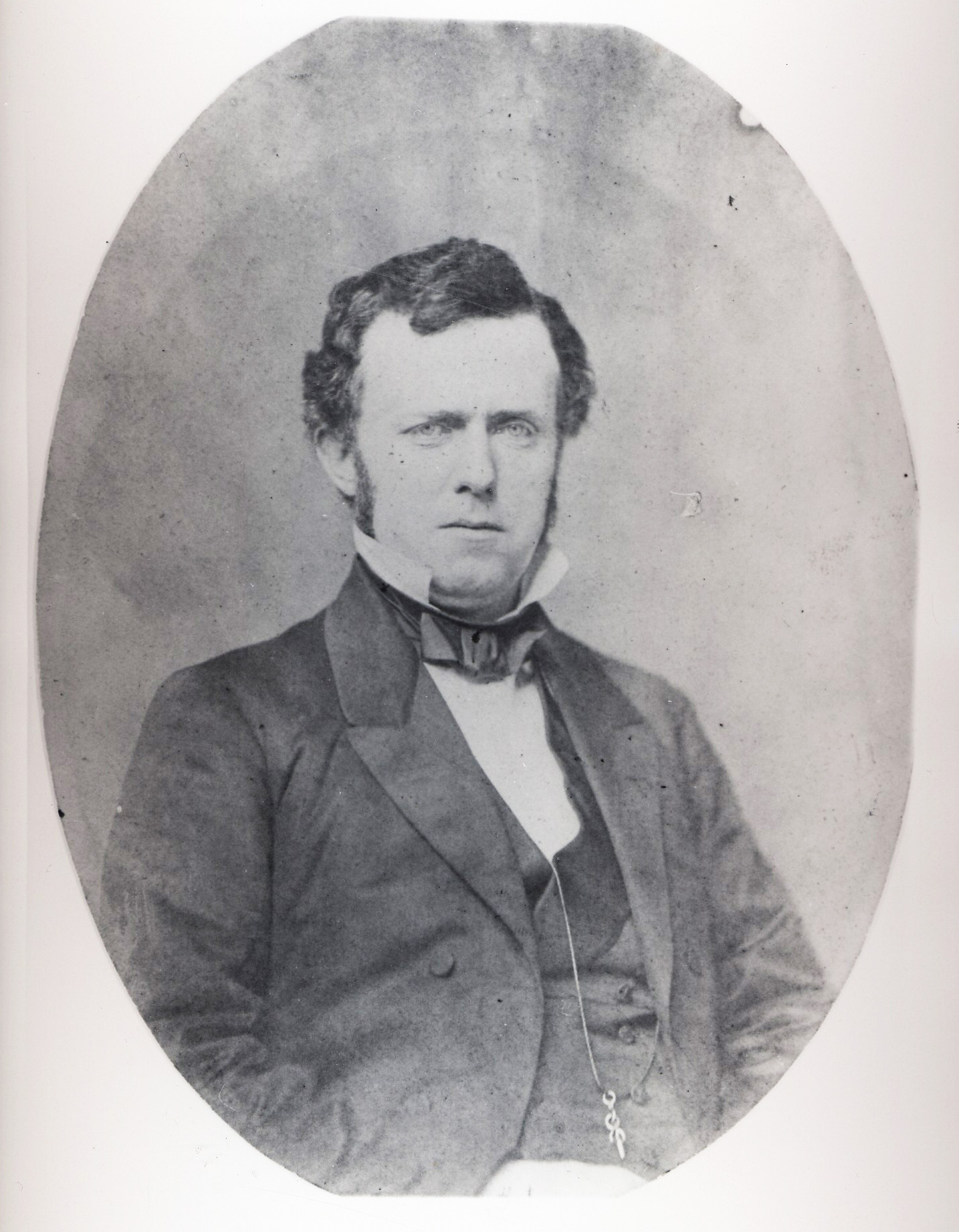

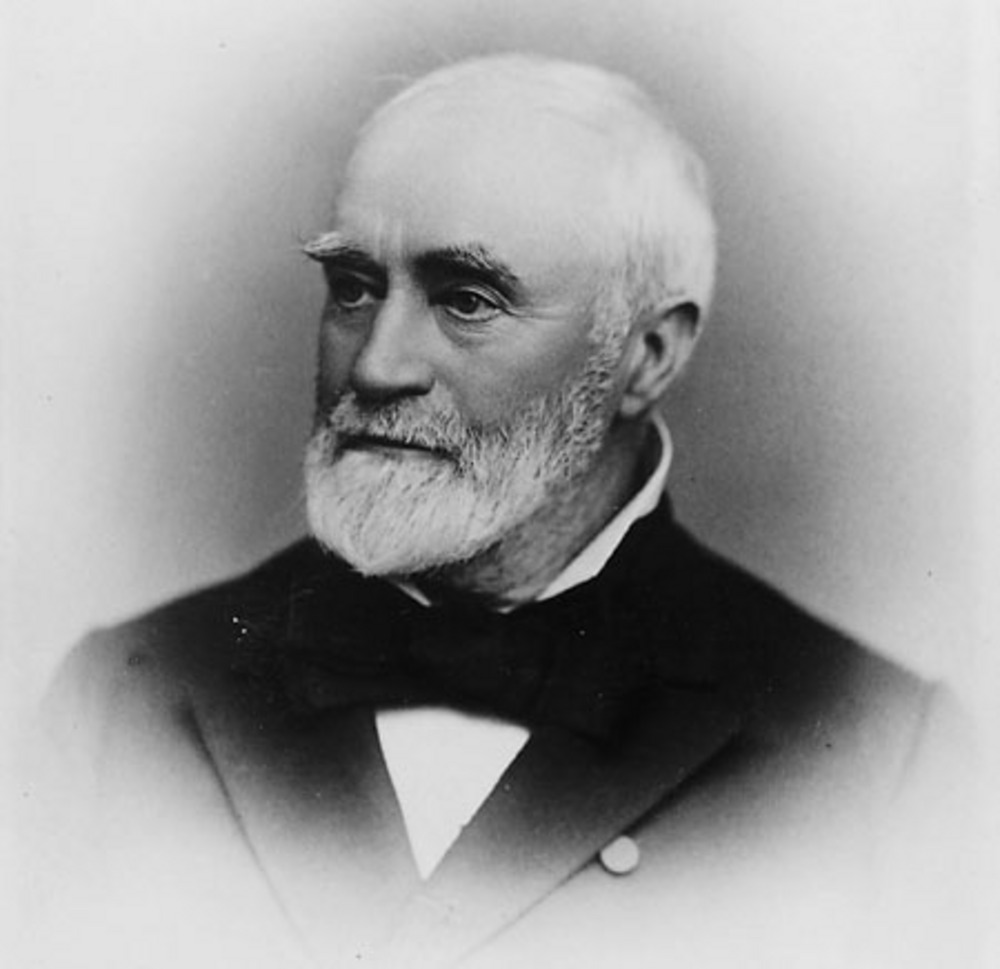

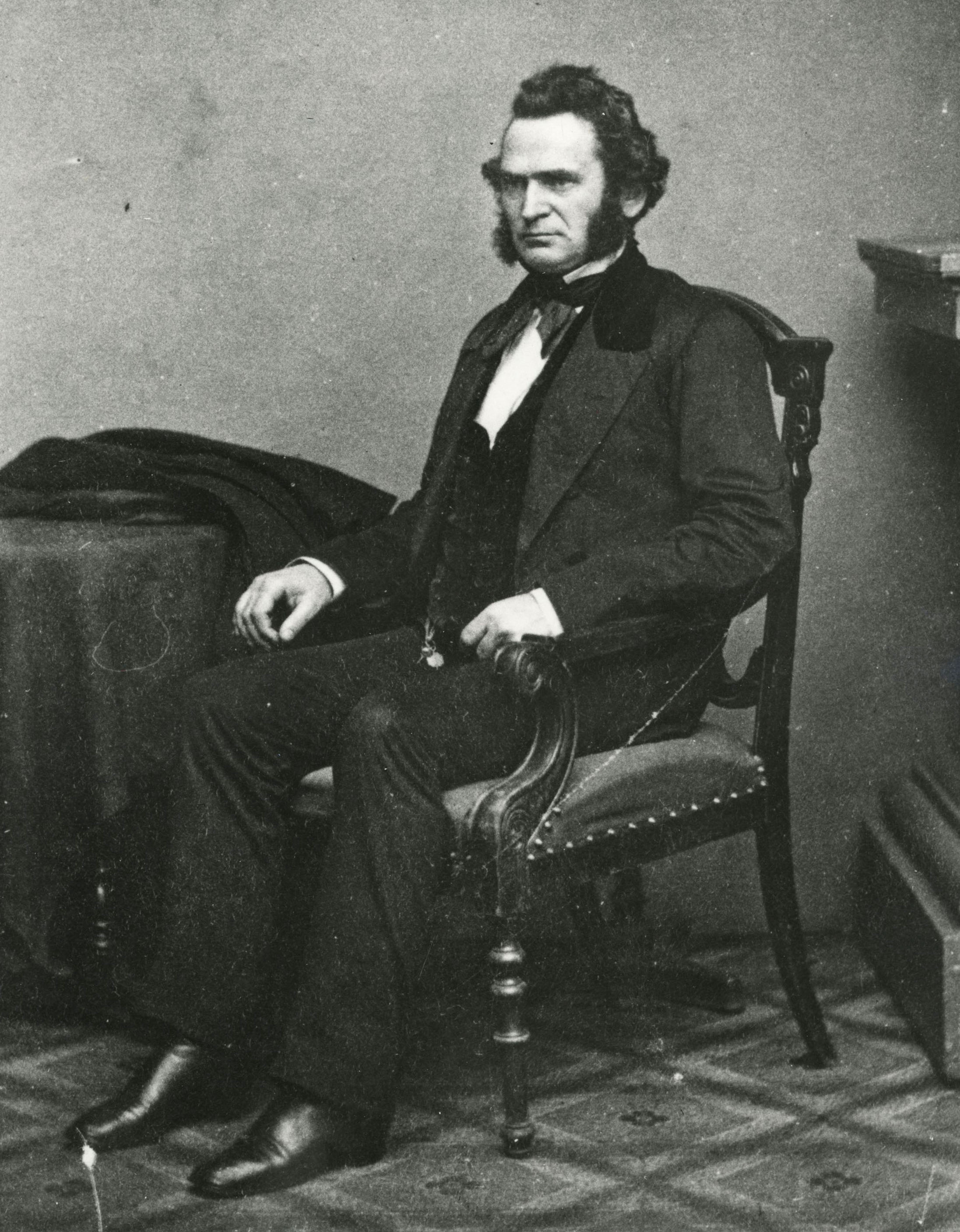

![]()

James Nesmith.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 67445, photo file 797b

-

![]()

George Curry.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 5219

-

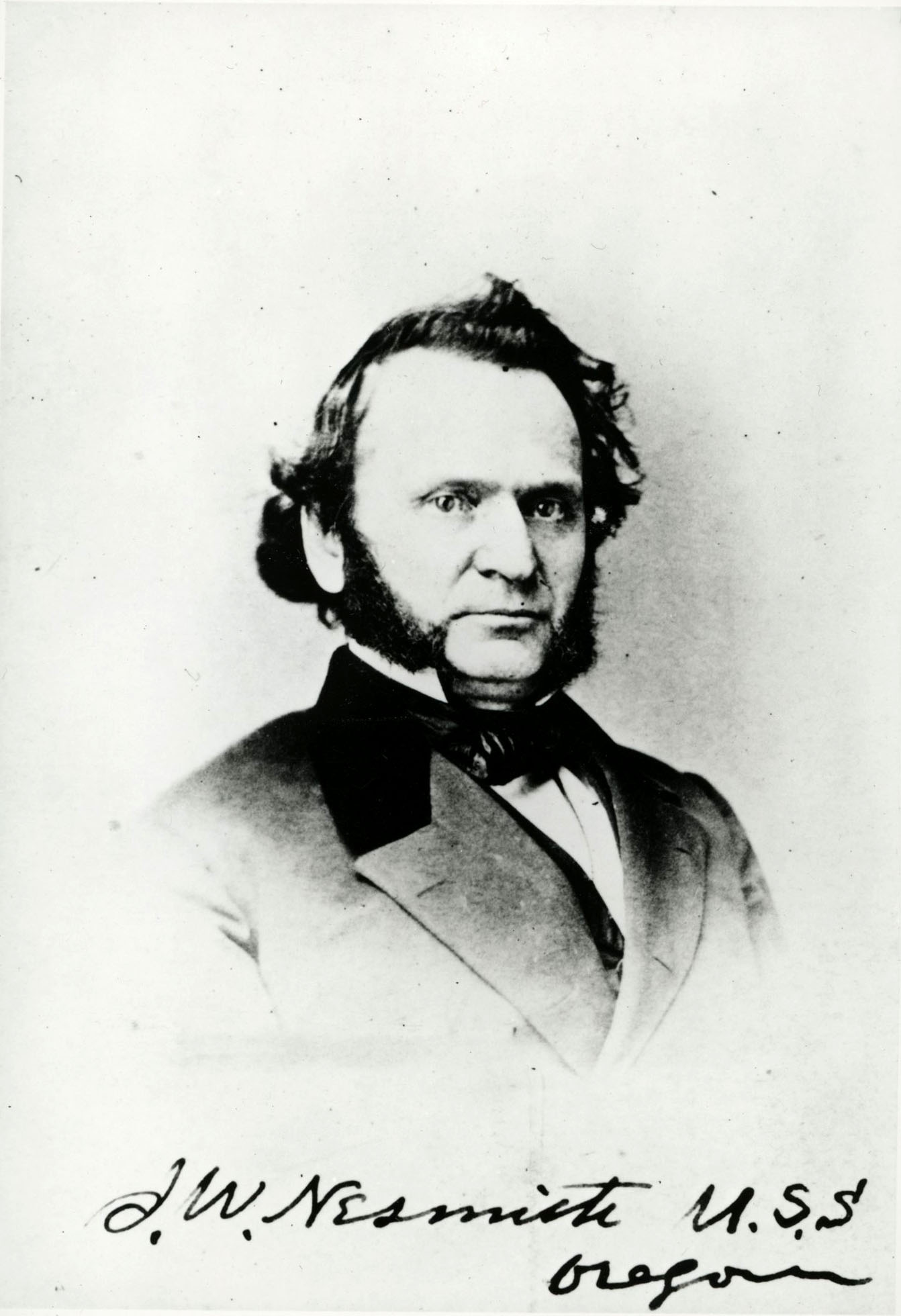

![]()

Delazon Smith as U.S. Senator, 1859.

Courtesy U.S. Senate Historical Office

-

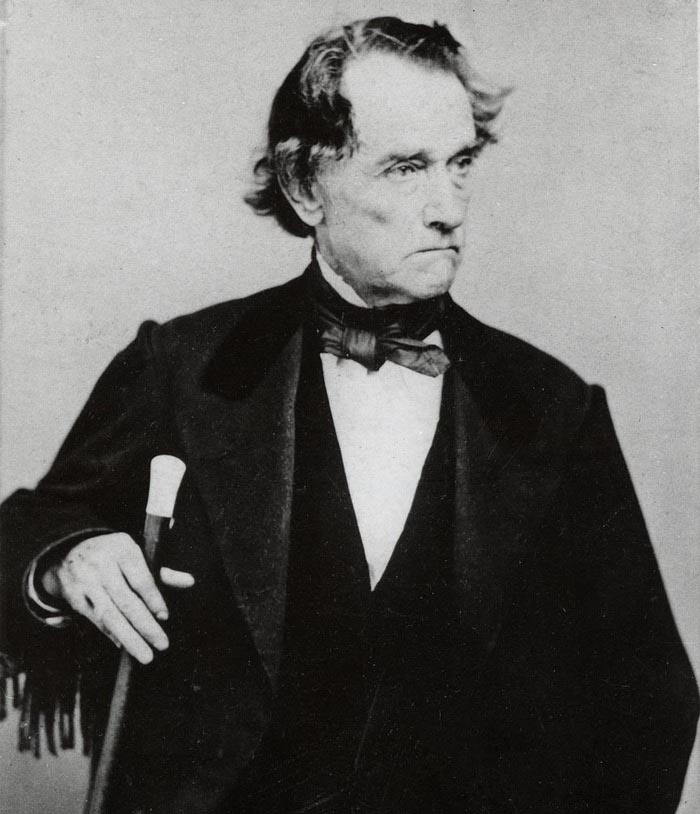

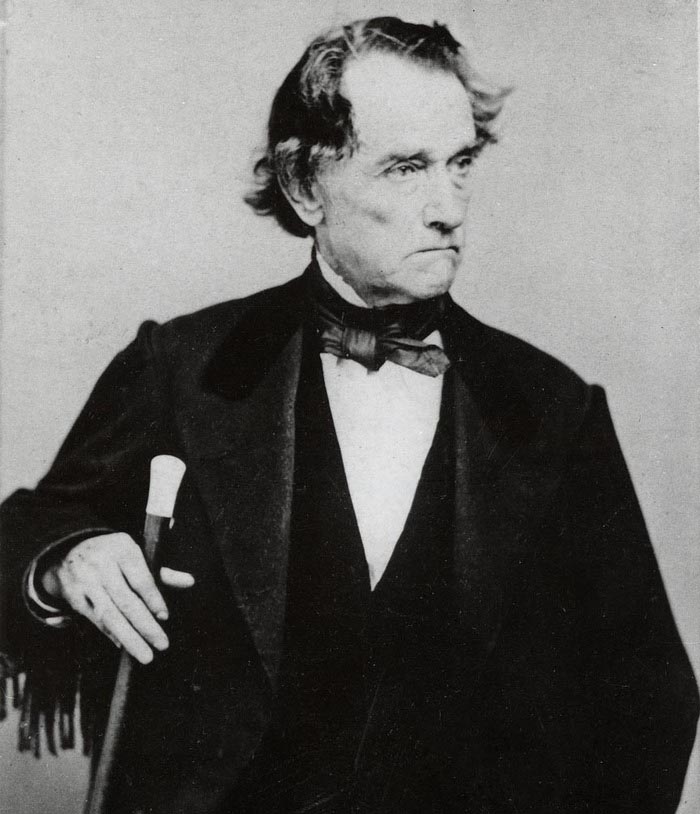

![General Joseph Lane, ba018668 OrHi 1703]()

General Joseph Lane.

General Joseph Lane, ba018668 OrHi 1703 Credit Oregon Historical Society Research Library

-

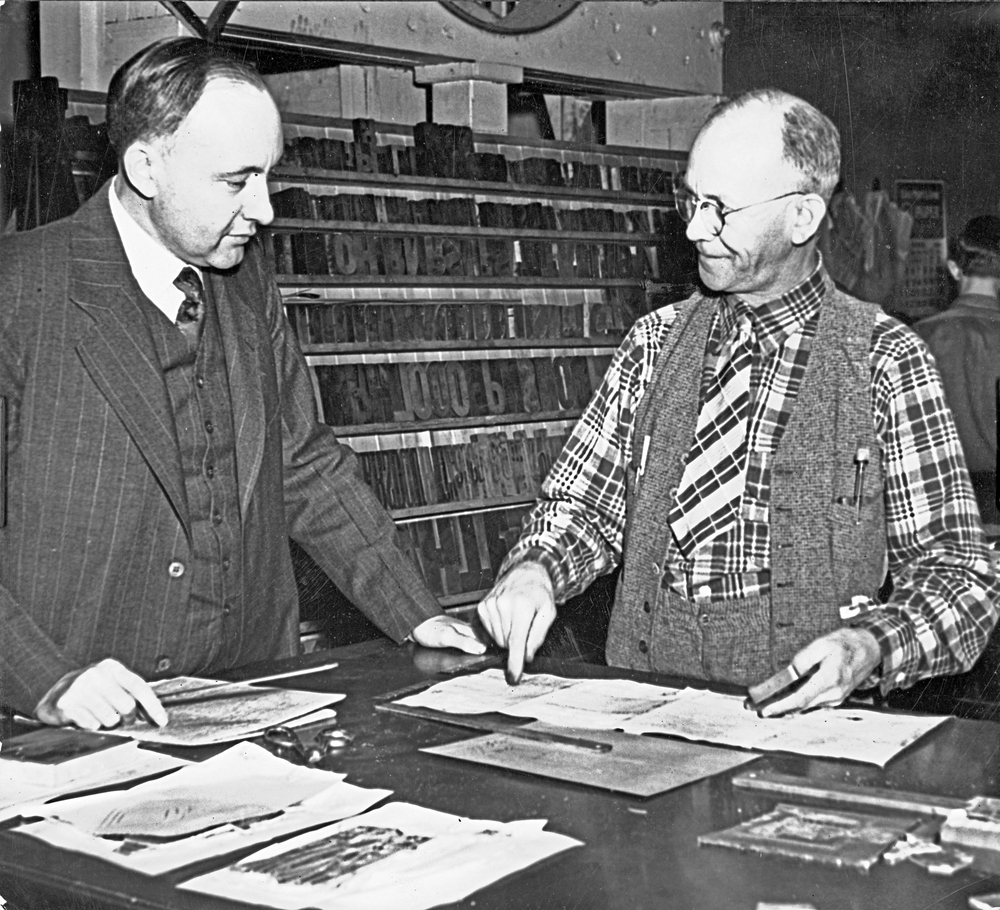

![]()

Thomas Jefferson Dryer.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 9149

Related Entries

-

![Asahel Bush (1824-1913)]()

Asahel Bush (1824-1913)

Asahel Bush was a key figure during Oregon's formative years, using the…

-

![Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon]()

Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon

Oregon's racial makeup has been shaped by three Black exclusion laws th…

-

![City of Salem]()

City of Salem

Salem, the capital of Oregon, is located at a crossroads of trade and t…

-

![Edward Baker (1811-1861)]()

Edward Baker (1811-1861)

Edward "Ned" D. Baker, who was born in London, England, on February 24,…

-

![Election of 1860]()

Election of 1860

The presidential election of 1860 was a turning point in Oregon politic…

-

![George Law Curry (1820-1878)]()

George Law Curry (1820-1878)

A significant figure in the years before Oregon became a state, George …

-

![James Willis Nesmith (1820–1885)]()

James Willis Nesmith (1820–1885)

James Nesmith was a prominent figure in the Oregon Territory and in Ore…

-

![Joseph Lane (1801-1881)]()

Joseph Lane (1801-1881)

Joseph Lane was the first governor of Oregon Territory. A leading Democ…

-

![Matthew Deady (1824-1893)]()

Matthew Deady (1824-1893)

Matthew Paul Deady was a lawyer, politician, and judge in the Oregon Te…

-

![Oregon Statesman]()

Oregon Statesman

Throughout its history, the Oregon Statesman has been a chronicler of O…

-

![The Oregonian]()

The Oregonian

The Oregonian, the oldest newspaper in continuous production west of Sa…

-

![Thomas Jefferson Dryer (1808–1879)]()

Thomas Jefferson Dryer (1808–1879)

Thomas J. Dryer was the first editor of the Portland Oregonian and an a…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Johannsen, Robert W. Frontier Politics and the Sectional Conflict: The Pacific Northwest on the Eve of the Civil War. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1955.

Mahoney, Barbara. The Salem Clique: Oregon’s Founding Brothers, Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2017.

Woodward, Walter Carlton. The Rise and Early History of Political Parties in Oregon, 1843-1868. Portland, Ore.: J.K. Gill, 1913.