The presidential election of 1860 was a turning point in Oregon political history. Oregon had become a state in 1859, and it was the first national election in which Oregonians participated. The election also increased the visibility of the Republican Party in the state and introduced far-western residents to Abraham Lincoln.

Americans generally and Oregonians specifically faced similar challenges in the months immediately before November 1860. The newly created Republican Party had done well in its first run for the White House in 1856, with explorer John C. Frémont as its candidate, but the party was uncertain about a new candidate until Lincoln won the nomination in May 1860. At the same time, the Democrats were fractiously divided over slavery. Unable to compromise on the issue, they had nominated two candidates: John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky, as the Southern Democratic who favored slavery, and Stephen Douglas of Illinois, standing for Northerners who supported popular sovereignty—a policy that allowed newly organized territories to decide on slavery. Unable to support the platforms of either major party, others joined the Constitutional Union Party and stood for John Bell of Tennessee. These four candidates and their parties divided Oregonians, as they did other Americans.

But there were differences in Oregon. Most Oregonians were Democrats in the 1840s and 1850s, and they were now being introduced to Republicans—a party formed in 1854 made up of an anti-slavery coalition that included Whigs and Free-Soilers. At first, the upstart Republicans in the state, although lacking a strong state leader, hoped to capitalize on the badly divided Democrats. The split in the Democrats loomed large, especially after the Salem Clique and Hard Democratic leader Asahel Bush, who supported popular sovereignty and took an antislavery stance, broke from the titular Soft Democrat spokesman Joseph Lane. Lane had dominated Oregon politics during the 1850s and was now the vice-presidential candidate for Breckinridge and the Southern, pro-slavery wing of the Democratic Party.

Oregon political parties followed national platforms, with a few local differences. The national Republican platform called for government-supported internal improvements, including homesteads and railroads, and called for no expansion of slavery into western territories. The fragmented Democrats offered a pro-slavery stance for the Breckinridge Southerners and the popular sovereignty platform for the Douglas Democrats. Those national platforms found favor in Oregon, but the differences lay in the willingness of more than a few Republicans to compromise in order to attract disillusioned Democrats and to capitalize on Lane’s declining popularity because of his support for slavery and possible secession.

Oregon Republicans found their needed political cheerleader and general in Edward D. Baker, a longtime friend of Lincoln’s who had recently led unsuccessful Republican organizing efforts in California. Invited to Oregon, Baker arrived in early 1860. An energetic campaigner and dynamic speaker, he crisscrossed the state, whipping up support for Republicans and making it clear that he would work with popular-sovereignty Democrats.

Baker's dynamic leadership and his willingness to court Douglas Democrats was a key to rising Republican strength. In the nineteenth century, when state legislatures elected U.S. senators, candidates had to pay special attention to members of the state legislature. In September, Baker and Douglas supporters, illustrating their acceptance of "fusion" as a pragmatic, acceptable policy (that is, gaining votes from both parties), urged the state legislature to name one senator from each party, which it did by selecting Baker from the Republicans and James Nesmith from the Hard Democrats. As Lane dropped from the scene—he was not even renominated to return to the U.S. Senate—Baker's star was quickly rising. The policy of fusion was not replicated on the national scene.

News about Lincoln as a possible presidential candidate came, early on, from three of his longtime friends who had moved to Oregon. Baker quickly spoke of Lincoln as a strong, electable leader. Even more enthusiastic was Anson G. Henry, Lincoln's personal doctor who had moved to Oregon in 1852. Henry was involved in bringing Baker to Oregon and pushed continually for candidate Lincoln. Simeon Francis, editor of the Sangamo Journal in Springfield, Illinois, arrived in late 1859 and immediately touted Lincoln in the Oregonian as a first-rate candidate. Once Lincoln won the Republican nomination, his name recognition in Oregon quickly accelerated.

Democratic divisions, more than Lincoln's rising popularity, determined the outcome of the presidential election in November, with the margin of his victory smaller in Oregon than it was nationally. In the country as a whole, Lincoln won 1,865,908 votes (39.8 percent), Douglas 1,380,202 (29.5 percent), Breckinridge 848,019 (18.1 percent), and Bell 590,901 (12.6 percent). Lincoln's win in Oregon was closer, with 5,344 votes (36.2 percent), but Breckinridge followed closely with 5,074 (34.4 percent) and Douglas with 4,131 (27.9 percent). Bell was obviously out of the running, with only 212 votes (1.4 percent). The two divided wings of the Democrats totaled about 9,200 votes in Oregon, nearly 4,000 more than Lincoln received. Even Lincoln confirmed that he had won the Oregon election by "the closest political bookkeeping that I know of."

Lincoln's narrow victory was followed by four years of policies that most Oregonians supported. His railroad, homestead, and agriculture legislation, as well as his diligent pursuit of victory in the horrendous Civil War, won over voters. As the Union Party candidate in 1864, his margin of victory was even greater than four years earlier. In his second election, Lincoln won support from 55 percent of the nation's voters.

The contest of 1860 should be remembered as one of Oregon's most important elections. Oregonians helped bring in a popular president, initiated Republican state control that continued for several decades, and introduced Oregonians to the national political process.

-

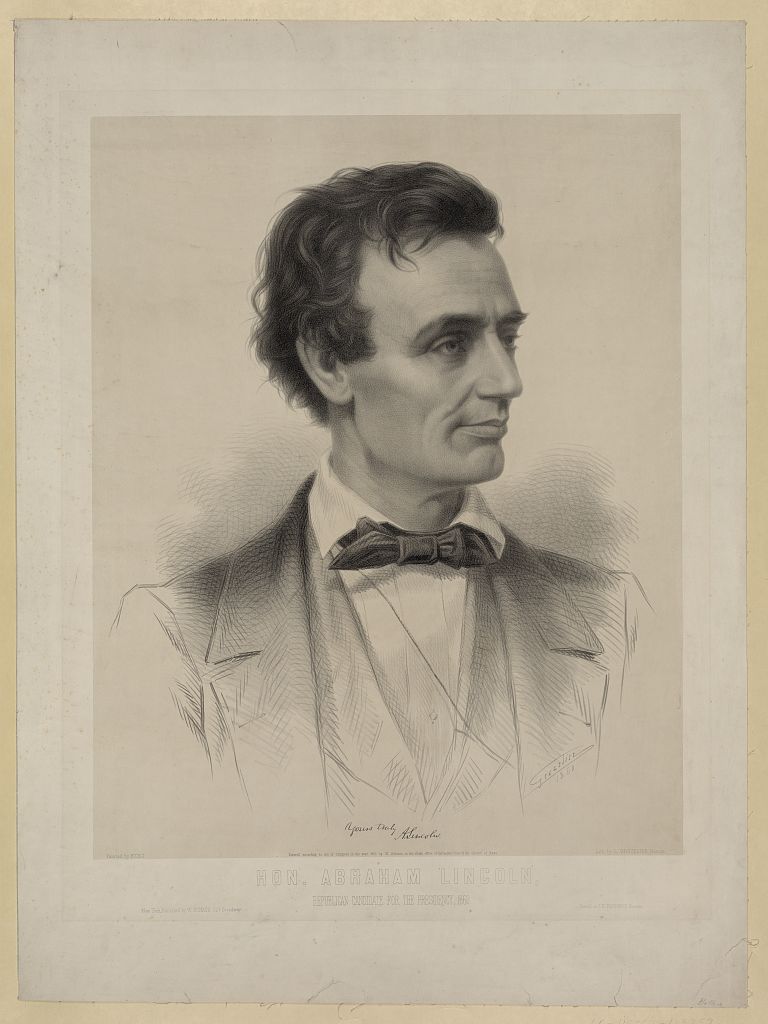

![]()

Hon. Abraham Lincoln, Republican candidate for presidency, 1860.

Courtesy Library of Congress, LC-DIG-pga-00380

-

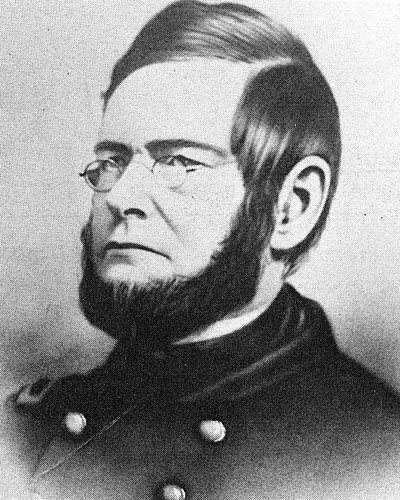

![]()

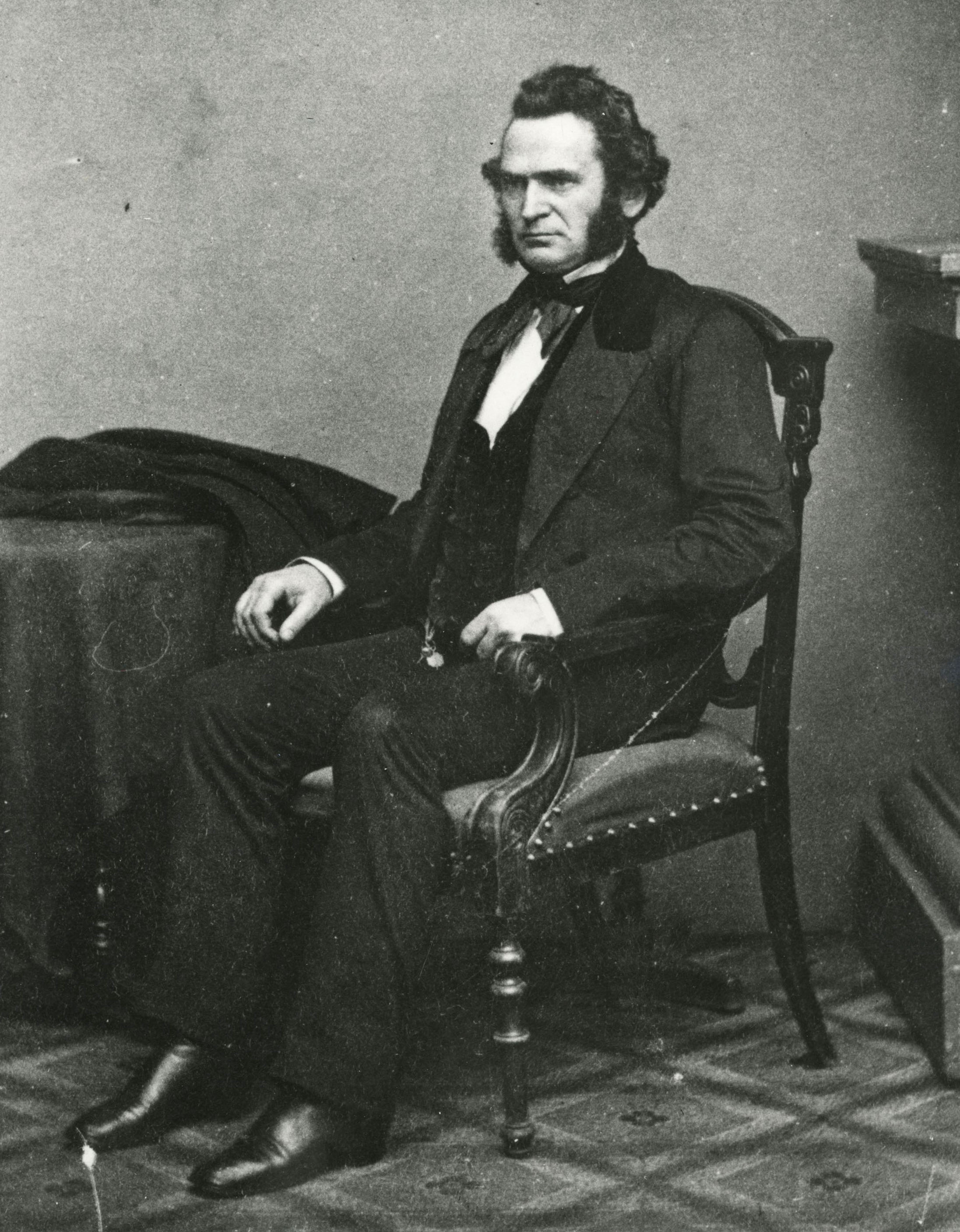

Edward Dickinson Baker.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb004278

-

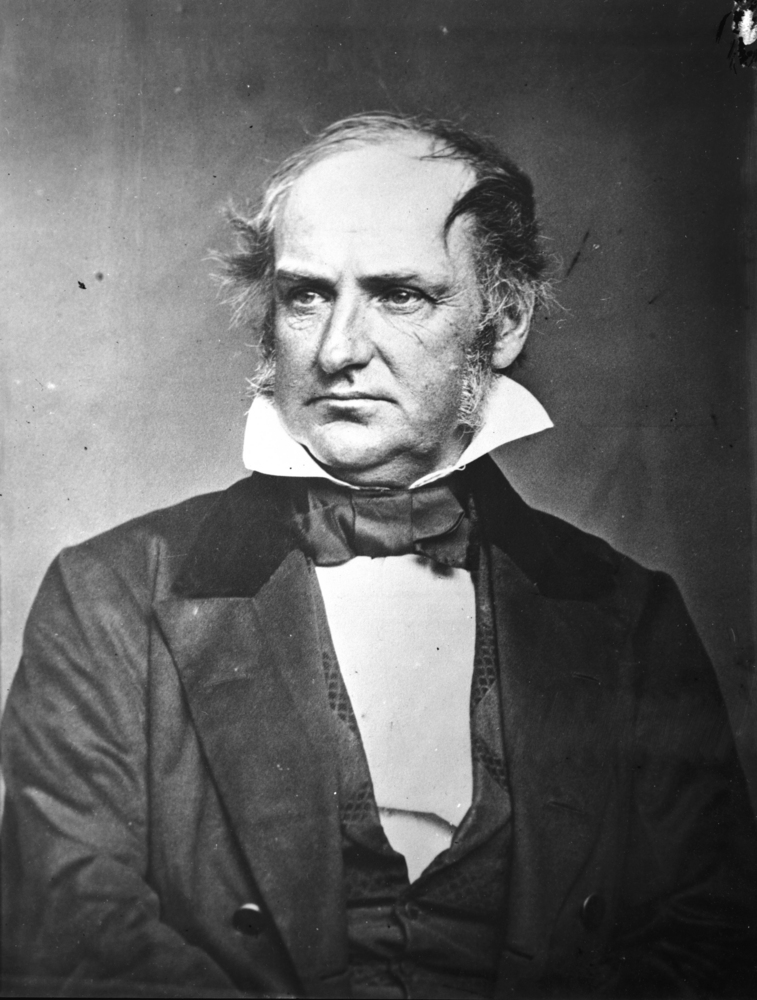

![]()

Dr. Anson G. Henry.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi9152, photo file 489

-

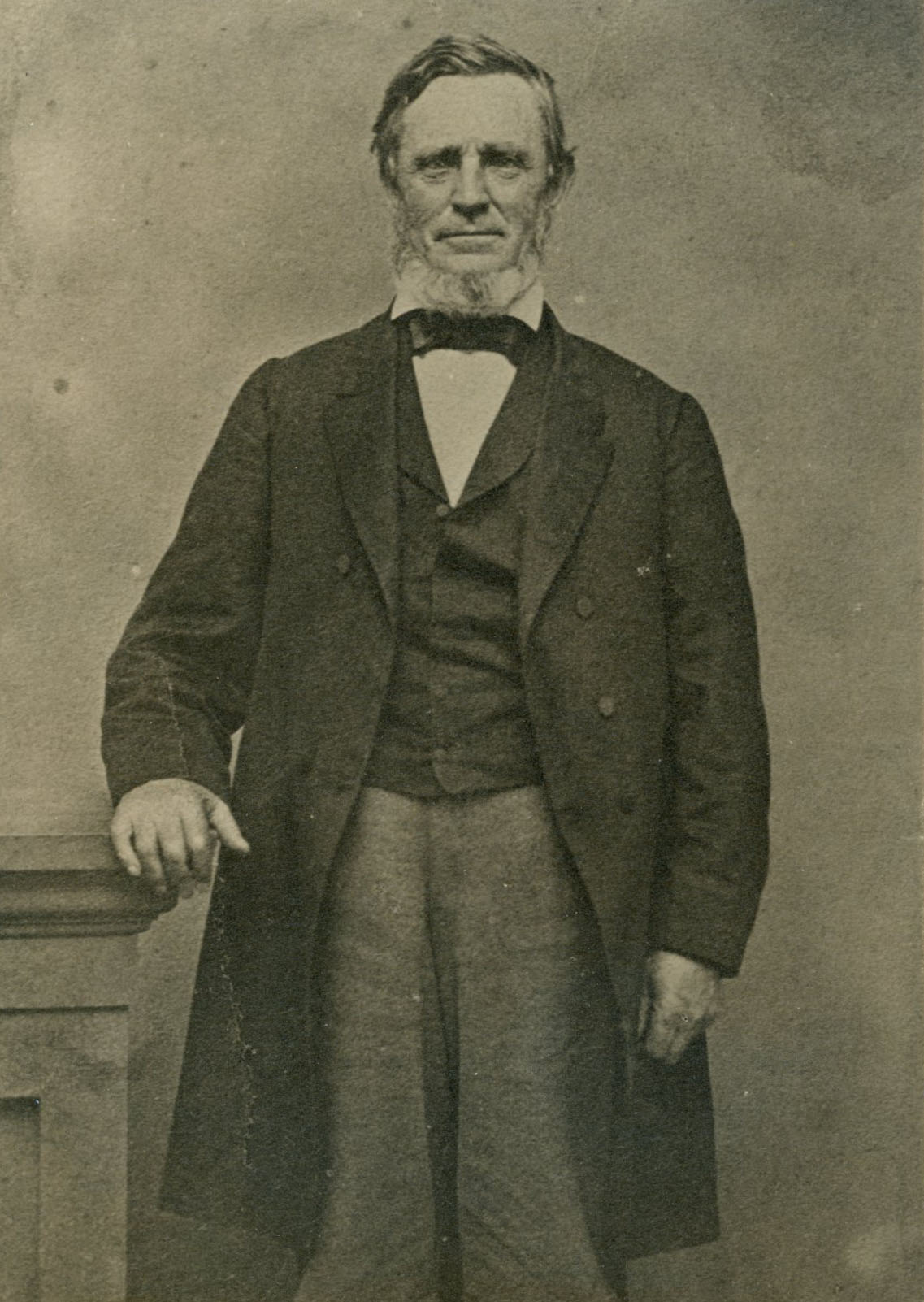

![]()

Francis Simeon.

Courtesy Illinois State Journal Register

-

![General Joseph Lane, ba018668 OrHi 1703]()

General Joseph Lane.

General Joseph Lane, ba018668 OrHi 1703 Credit Oregon Historical Society Research Library

-

![]()

A Portrait of Abraham Lincoln during his presidency..

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Cartes de Visite, 655B1

-

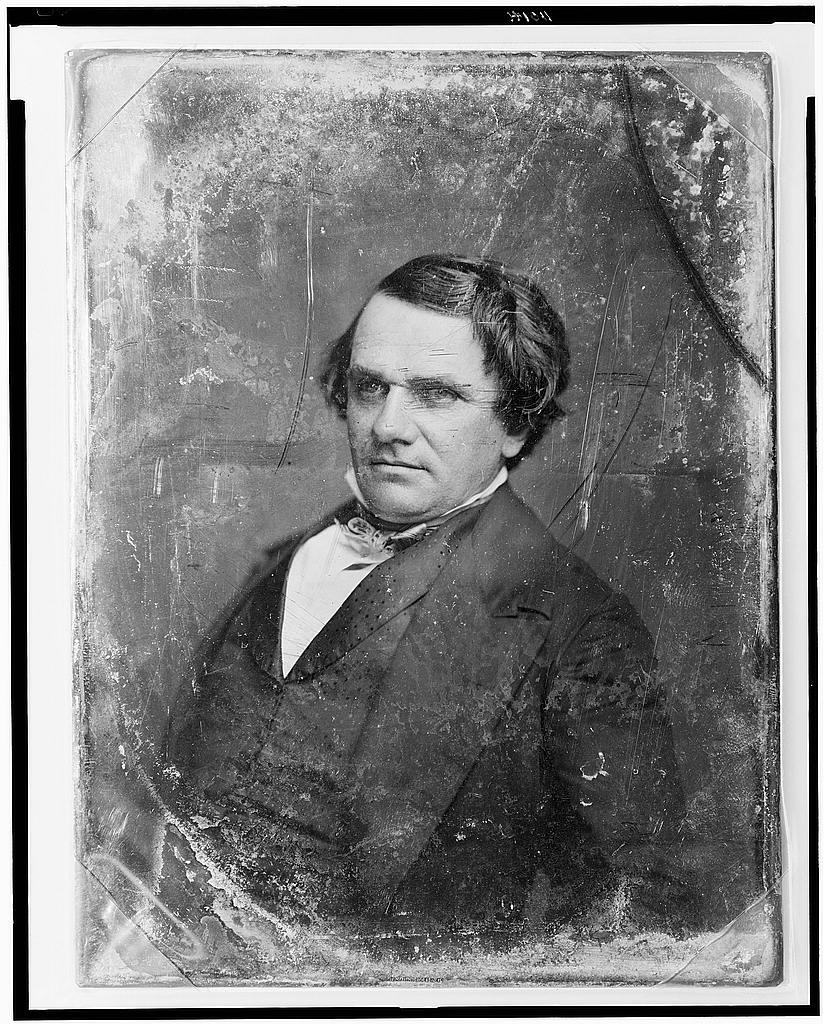

![]()

Stephen Douglas, c.1850s.

Courtesy Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-110141

-

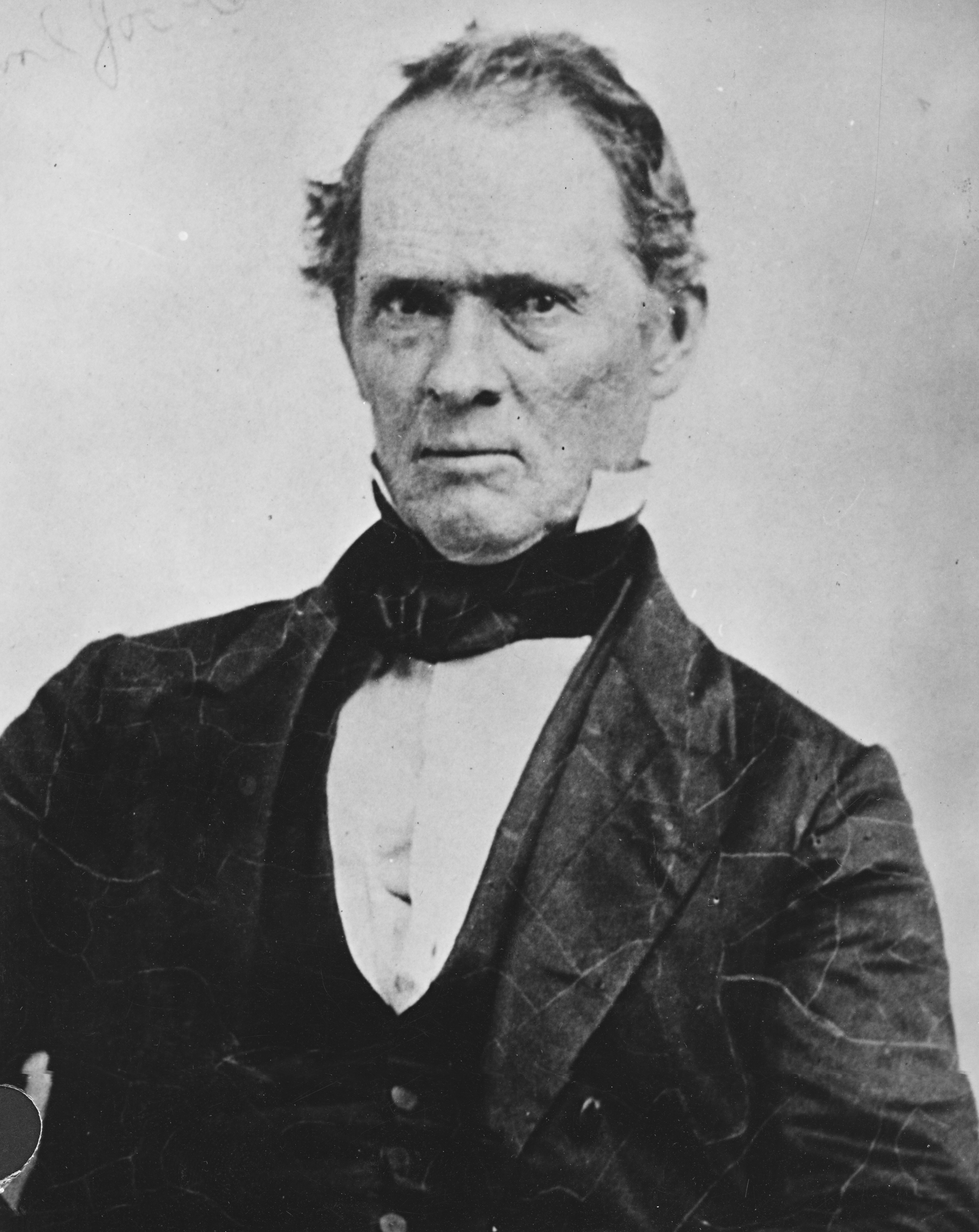

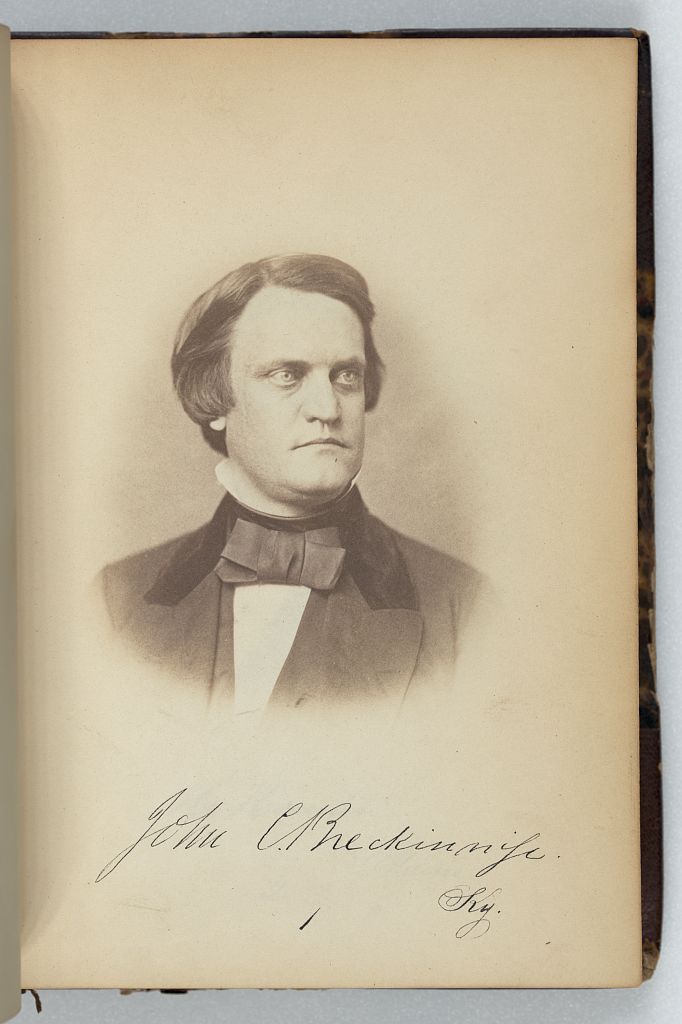

![]()

John Breckinridge, senator from Kentucky, 1859.

Courtesy Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsa-26540

-

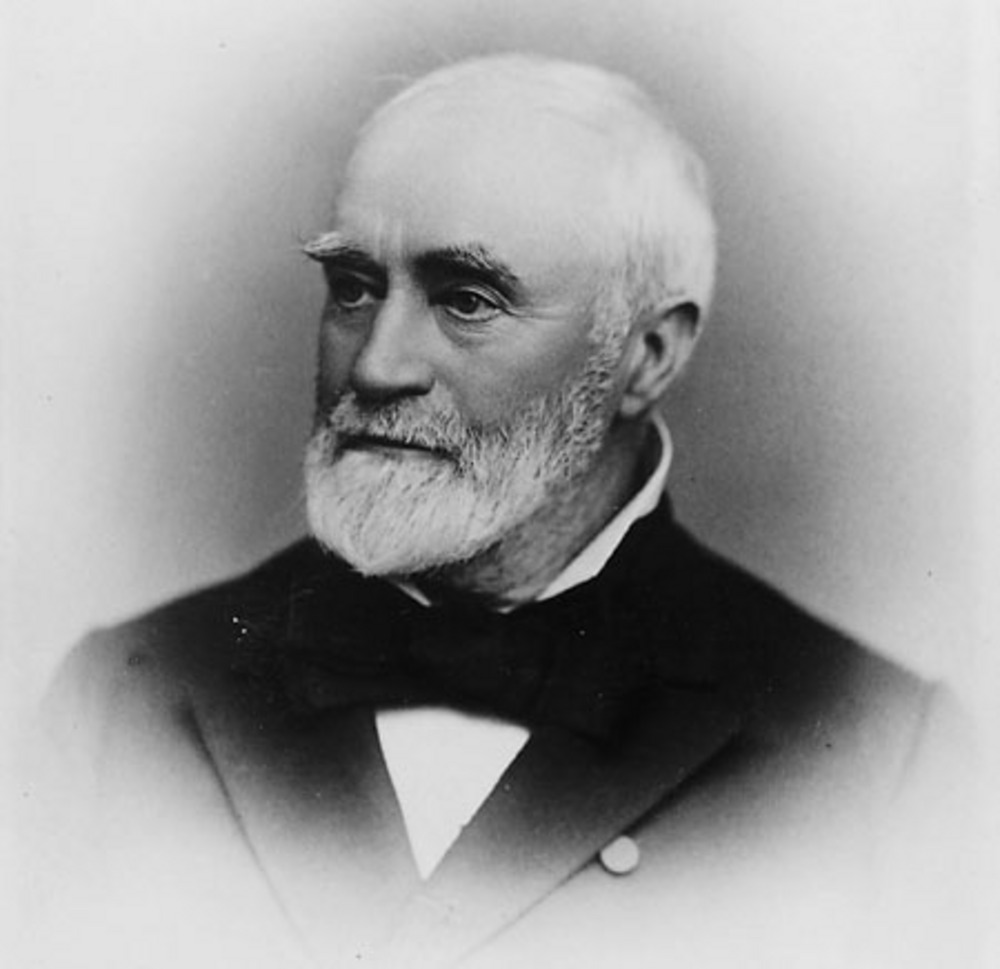

![]()

John Bell, senator from Tennessee, c. 1850s.

Courtesy Library of Congress, LC-USCZ62-110028

Related Entries

-

![Asahel Bush (1824-1913)]()

Asahel Bush (1824-1913)

Asahel Bush was a key figure during Oregon's formative years, using the…

-

![City of Salem]()

City of Salem

Salem, the capital of Oregon, is located at a crossroads of trade and t…

-

![Edward Baker (1811-1861)]()

Edward Baker (1811-1861)

Edward "Ned" D. Baker, who was born in London, England, on February 24,…

-

![James Willis Nesmith (1820–1885)]()

James Willis Nesmith (1820–1885)

James Nesmith was a prominent figure in the Oregon Territory and in Ore…

-

![Joseph Lane (1801-1881)]()

Joseph Lane (1801-1881)

Joseph Lane was the first governor of Oregon Territory. A leading Democ…