Matthew Paul Deady was a lawyer, politician, and judge in the Oregon Territory. When Oregon became a state in 1859, Deady was named Oregon's first U.S. district court judge, and he sat at the federal court in Portland until his death more than three decades later.

Born in Talbot County, Maryland, on May 12, 1824, Deady was the oldest of five children. His father was a poor Irish immigrant who earned a living as a schoolteacher. The family lived in Maryland, Virginia (present-day West Virginia), and Ohio until Deady's mother died of tuberculosis in 1834. Deady then lived with his grandfather in Baltimore and worked at his grocery store until the family was reunited in Ohio two years later.

At the age of sixteen, Deady left home and apprenticed to a blacksmith, but a term at the Barnesville Academy inspired him to pursue a more intellectual vocation. He taught school briefly, and by 1846 he was studying law under William Kennon, Sr. He earned admission to the Ohio State Bar a year later.

Deady arrived in Oregon Territory in November 1849, and by March 1850 he was arguing his first case in an Oregon court. That summer he won election to the territorial legislature, where he compiled the first book of Oregon laws and befriended General Joseph Lane. Through Lane's influence, President Franklin Pierce appointed Deady to the territorial supreme court in 1853, and he took the office the following year.

In August 1857, a convention met in Salem to frame a state constitution, and Deady was elected its president. The delegates chose not to settle the question of slavery, and put it to a popular vote. While the people of Oregon voted for a free state, Deady defended slavery and ran for state supreme court in 1858 on a pro-slavery ticket. He won the election, but accepted President James Buchanan's appointment to the federal bench instead. He then campaigned vigorously for Joseph Lane during the 1860 campaign, fearing Lincoln was too radical. Secession changed his outlook and he became a Republican during the Civil War, but he never repudiated his defense of slavery.

Deady's attitude toward slavery and his abhorrence of Southern rebellion derived from his reverence for the law. In later years, that same reverence led to Deady's steadfast protection of Chinese immigrants against white hostility. In case after case, he cited the precedent of treaties between the United States and China over state and local laws designed to oppress and harass Chinese immigrants. These rulings may have reflected an evolution in Deady's views, as evidenced by his 1882 decision in On Yuen Hai Co. v. Ross: "The statute...is not only contrary to the treaty with China, but to the dictates of natural justice."

Deady also showed an inclination toward "natural justice" in other areas of the law. In admiralty cases, he repeatedly rendered decisions that favored ordinary seamen and small merchants against exploitative or negligent officers and shipping companies. He showed a similar skepticism toward terrestrial corporations,consistently rendering decisions against companies he believed were threatening the public interest. In Gilmore v. Northern Pacific Railroad Company (1884), for instance, he rejected the "fellow servant rule," which nineteenth-century corporations had used to escape liability for workplace injuries by laying the blame on a particular employee or supervisor. Deady instead felt the company should be held accountable for the safety of its workers.

When it came to land disputes, however, Deady was more inclined to a strict interpretation of the law. He tended to favor holders of legal title over settlers who had purchased murky titles in good faith, and many of his decisions were overturned by Circuit Court Judge Lorenzo Sawyer, who emphasized "intrinsic justice." But not all of Deady's land-law rulings resulted in inequitable outcomes. In Pennoyer v. Neff (1878), for instance, Deady ruled in favor of Marcus Neff, who had been out of the state when his lawyer John H. Mitchell took possession of his land claim in lieu of payment for legal services. Deady concluded that Mitchell's half-hearted attempts to contact Neff had been insufficient, and the U.S. Supreme Court later affirmed Deady's conclusion in a landmark decision.

Deady single-handedly codified the state's laws in 1864 and 1872, cementing the reputation he had earned as "Oregon's Justinian" during the territorial period. Moreover, he drafted several of the state's statutes himself, including the law governing corporations and the incorporation act for the City of Portland.

Despite his responsibilities and accomplishments as a jurist, Deady found his salary insufficient to cover his expenses, in part because the paper money paid by the federal government during and after the Civil War was not worth its face value. To supplement his income, Deady became a correspondent for the San Francisco Bulletin in 1863. His talents as a writer of more than legal opinions are showcased in his 1868 essay for Overland Monthly, "Portland-on-Wallamet." He wrote, "Among the fir-clad hills and broad rich valleys of Oregon, the bucolic instinct still lingers," a statement as true today as it was in his lifetime.

Even with all his paid responsibilities, Deady found time for charitable works. He helped organize the Library Association of Portland, participated in the outreach activities of Trinity Episcopal Church, and served as president of the University of Oregon Board of Regents for twenty years. The University of Oregon's Deady Hall (1876)—the first structure built on campus and still in use—was named for him in 1893.

Deady's health began to fail in the summer of 1892, and doctors eventually concluded he had suffered a stroke. Through sheer force of will he continued to hold court through the winter. He died on March 24, 1893.

Deady had presided over the federal court in Oregon since it joined the Union, and his hand in state law and politics reached back further still. For influence in the state's development, few men or women may ever rival Judge Matthew Deady.

-

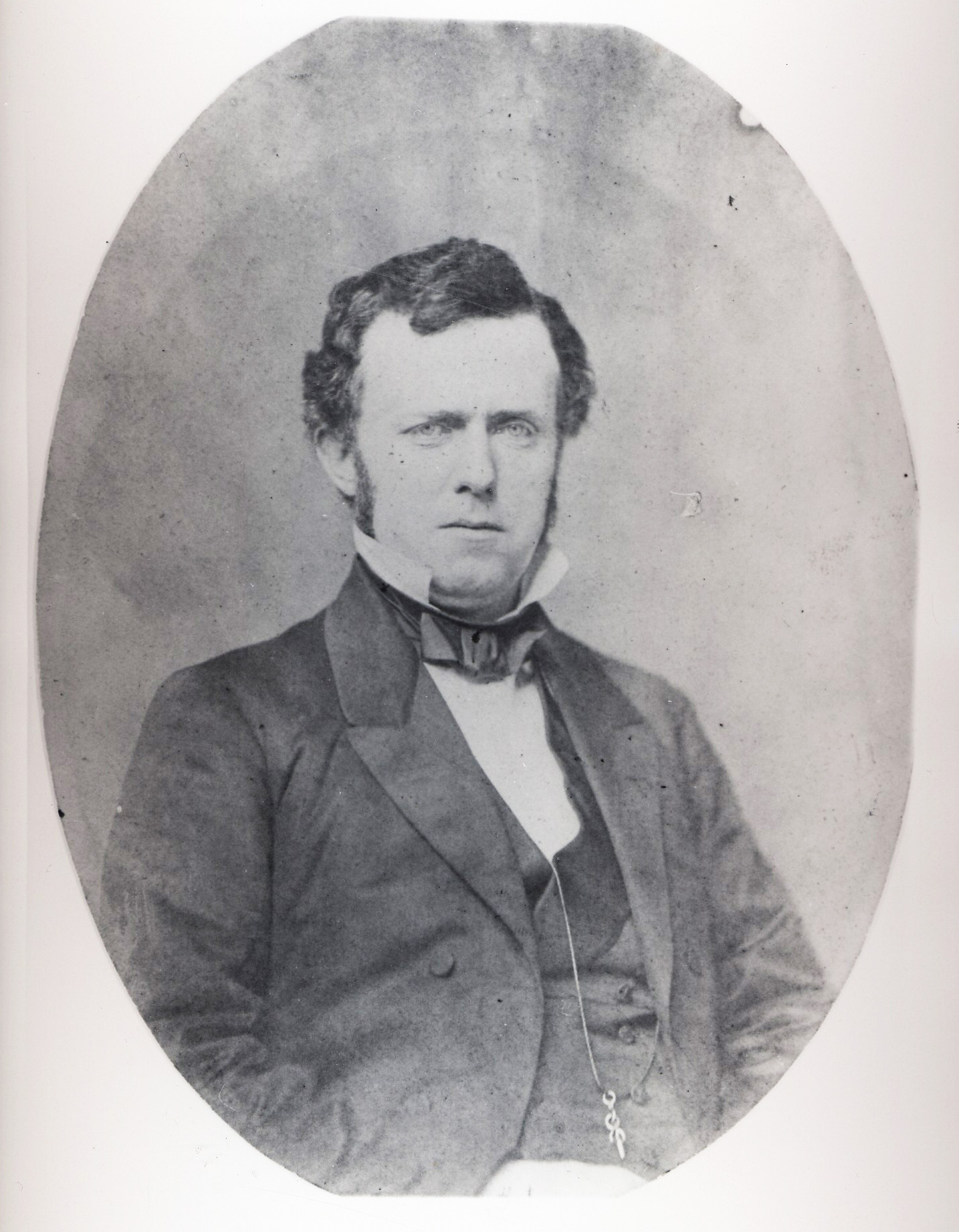

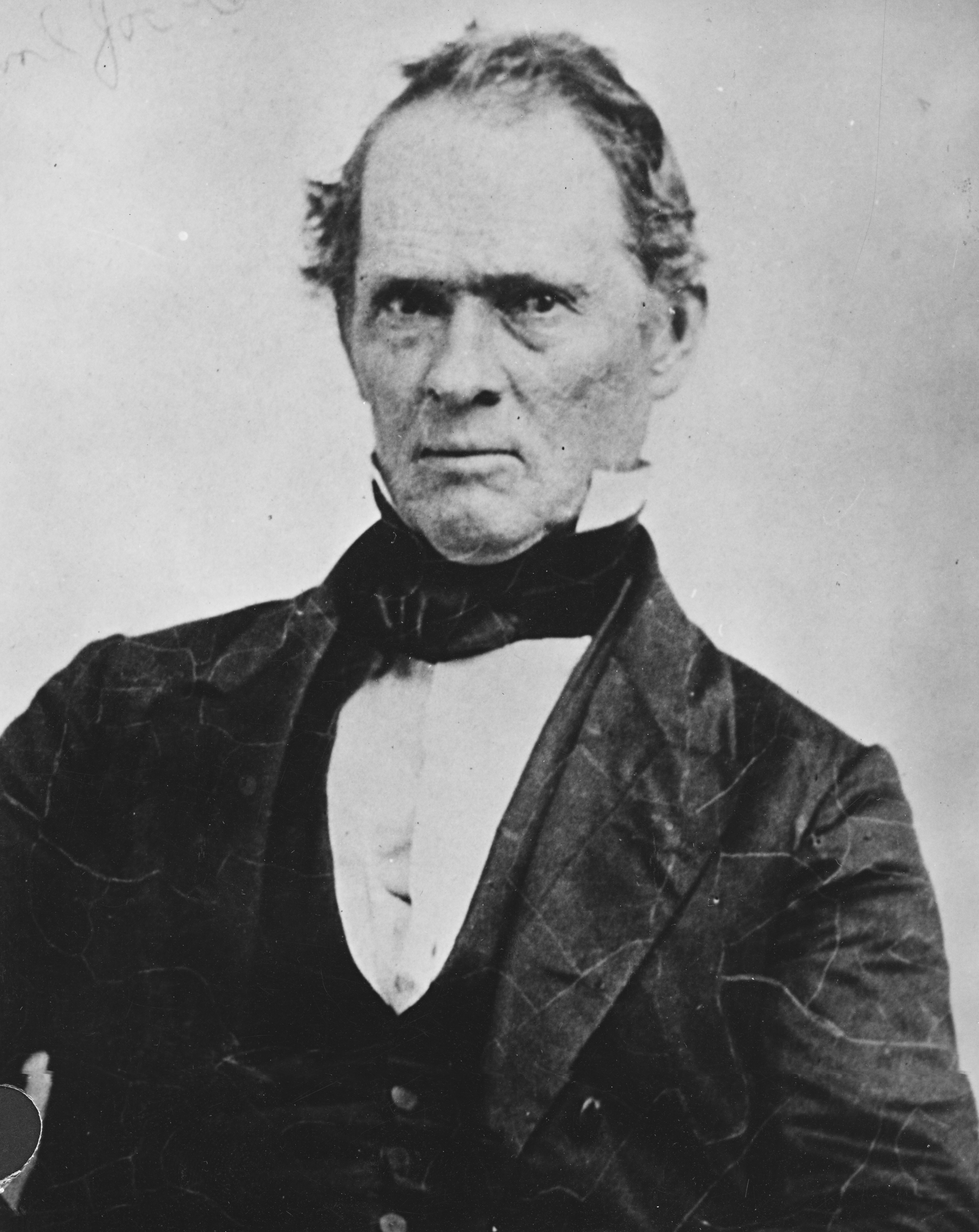

![Matthew P. Deady at age 35, about 1859.]()

Deady, Matthew P., OrHi 63119.

Matthew P. Deady at age 35, about 1859. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Libr., OrHi 63119

-

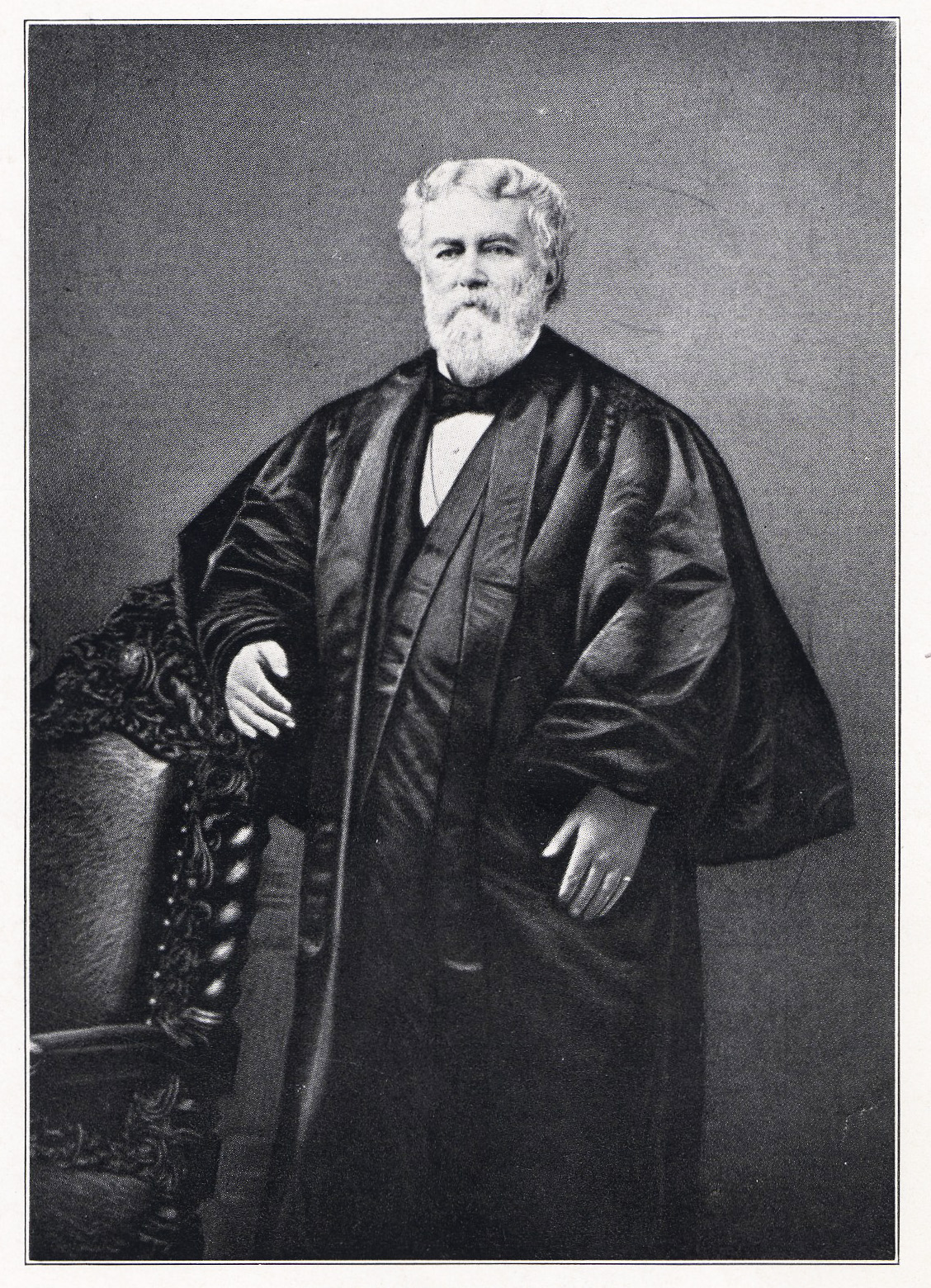

![Matthew P. Deady.]()

Deady, Matthew P, in robes, OrHi 77105.

Matthew P. Deady. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Libr., OrHi 77105

-

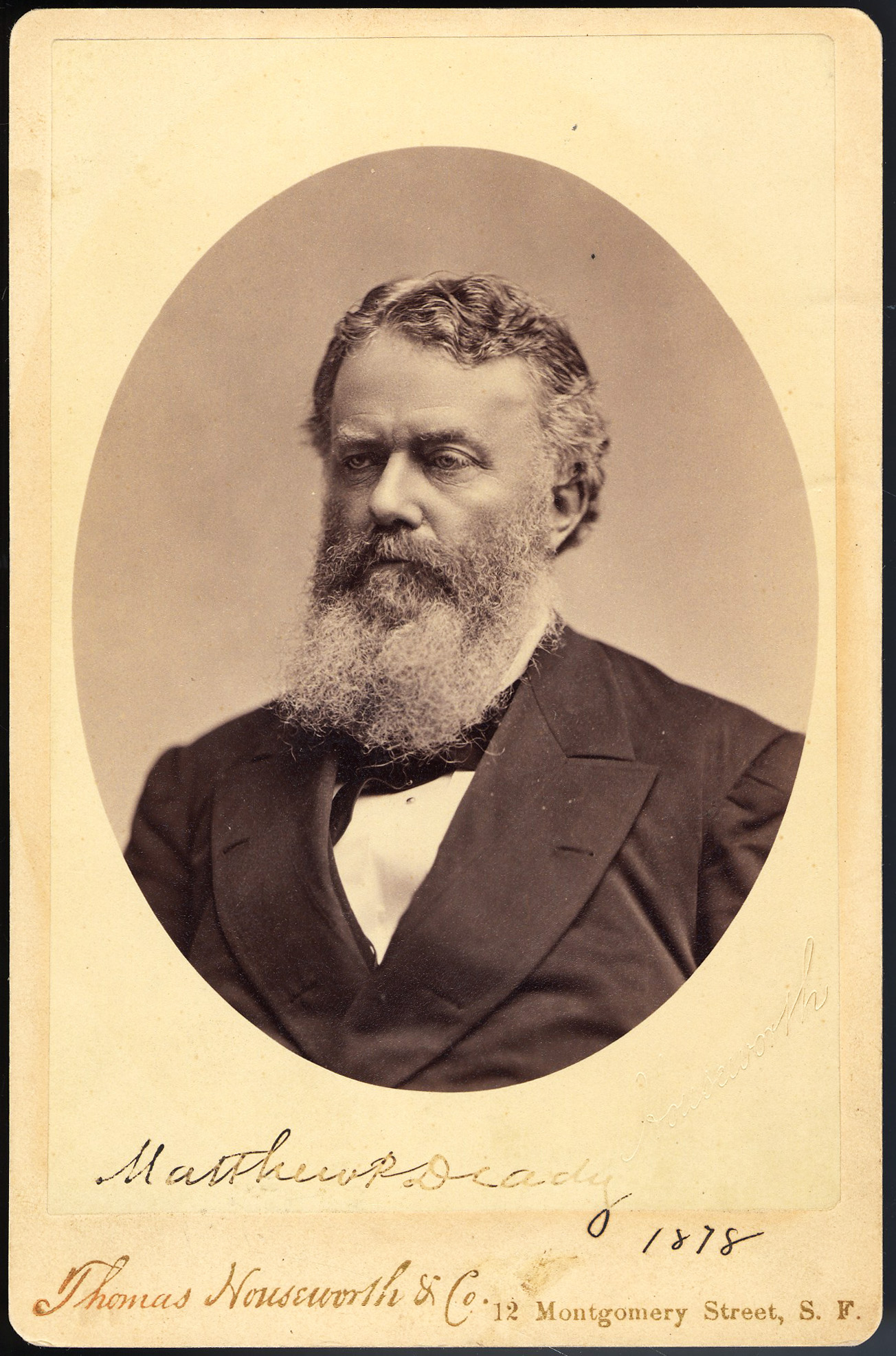

![Matthew P. Deady in 1878.]()

Deady, Matthew P, 1878, OrHi 47403.

Matthew P. Deady in 1878. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Libr., OrHi 47403

-

![Lucy Ann Deady (nee Henderson), wife of Matthew P. Deady.]()

Deady, Lucy Ann, OrHi 59557.

Lucy Ann Deady (nee Henderson), wife of Matthew P. Deady. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Libr., OrHi 59557

-

![Celebrants of Matthew Deady's birthday, Aug. 1886, Yaquina Bay. Matthew Deady is standing far right with beard and cap.]()

Deady, Matthew P, with others, Aug 1886, neg 67021.

Celebrants of Matthew Deady's birthday, Aug. 1886, Yaquina Bay. Matthew Deady is standing far right with beard and cap. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Libr., neg 67021

-

Deady Hall, U of O, ca 1900.

Deady Hall, 1201 Old Campus Ln., Univ. of Oregon, about 1900. Photo Michael E. Shellenbarger, Univ. of Oreg., Architecture & Allied Arts Libr., Visual Resources Collec., pna_07870

Related Entries

-

![John Hipple Mitchell (1835-1905)]()

John Hipple Mitchell (1835-1905)

John Hipple Mitchell was a Portland lawyer and politician whose long ca…

-

![Joseph Lane (1801-1881)]()

Joseph Lane (1801-1881)

Joseph Lane was the first governor of Oregon Territory. A leading Democ…

-

![Trinity Episcopal Cathedral]()

Trinity Episcopal Cathedral

The history of Trinity Episcopal Church, now the cathedral of the Dioce…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Clark, Malcolm. Pharisee Among Philistines: The Diary of Judge Matthew P. Deady, 1871-1892. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 1975 .

Gaston, Joseph. Portland, Oregon: Its History and Builders, vol. 3. Portland, Oreg.: S.J. Clarke, 1911.

Mooney, Ralph James. "The Deady Years, 1859-1893," In Carolyn M. Buan, ed., The First Duty: A History of the U.S. District Court for Oregon. Portland: U.S. District Court of Oregon Historical Society, 1993.