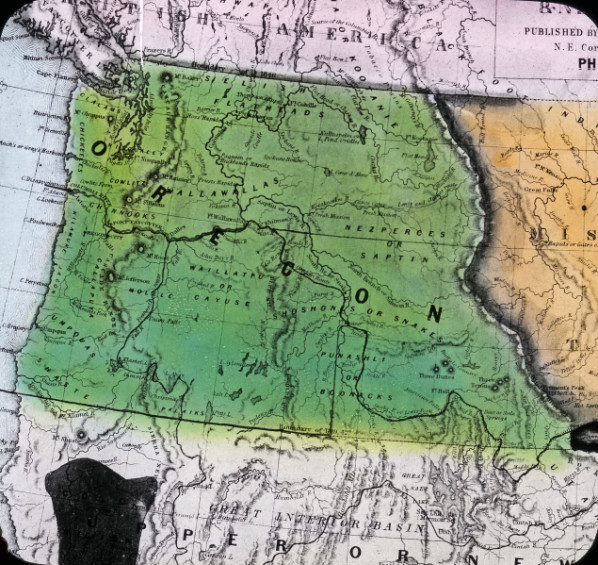

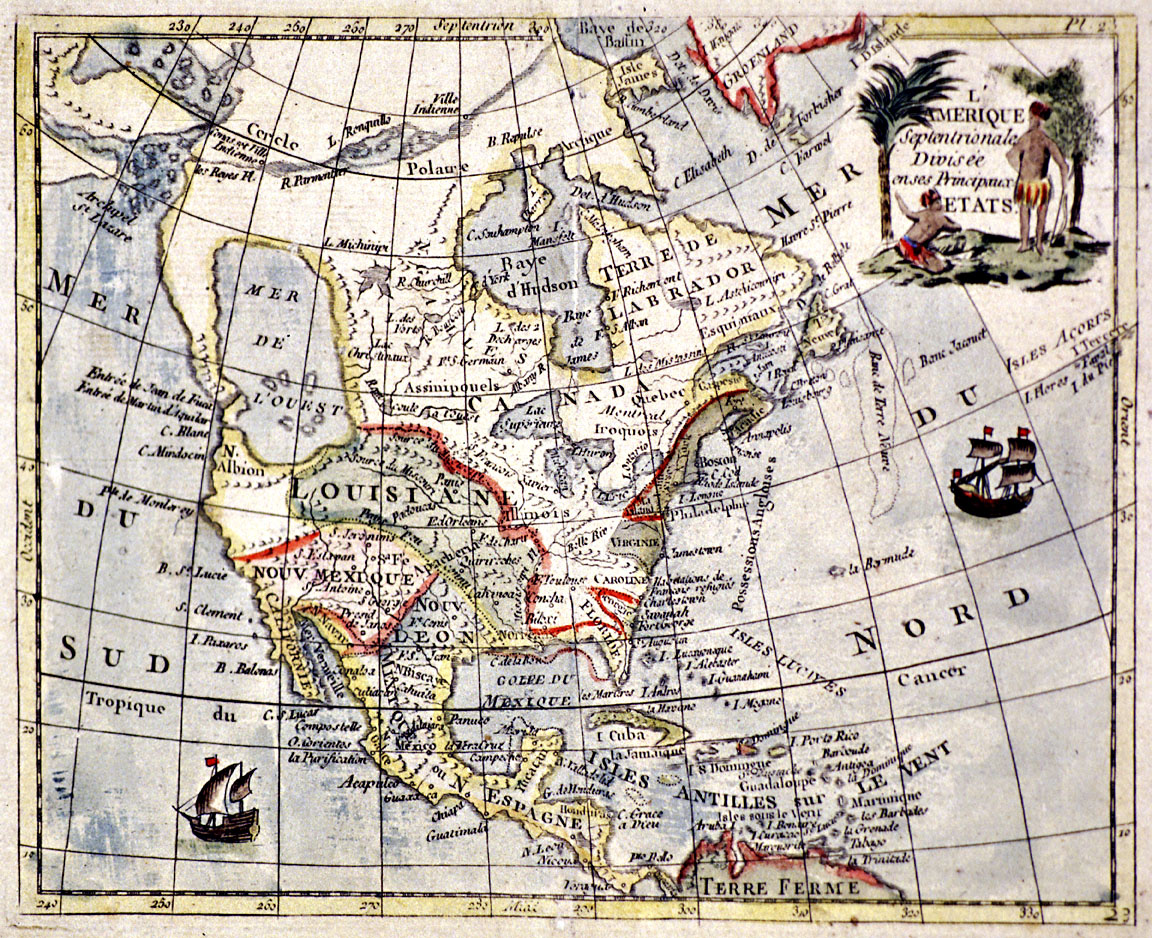

“The Oregon boundary question,” historian Frederick Merk concluded, “was a diplomatic problem involving a kernel of reality and an enormous husk.” The eventual existence of the states of Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and Montana depended on solving the so-called Oregon Question, a three-decade dispute between Great Britain and the United States. The disagreement pivoted on the nations’ competing claims to a vast territory between the Pacific Ocean and the Continental Divide, bounded by latitudes 54°40' N and 42° N (the present-day southern border of Alaska with British Columbia and the Oregon-California state line).

Competition between the two nations over the region dated to the 1780s, when control of the sea otter trade was a primary issue; but the War of 1812 marked the onset of the “diplomatic problem”—the Oregon Question. The “husk” of the issue comprised thirty years of political wrangling between Great Britain and the United States, which often reflected as much about each nation’s domestic politics as it did the political future of Oregon.

Residue of War

Negotiated in late 1814 and ratified by the U.S. Senate in 1815, the Treaty of Ghent ended the War of 1812 between Great Britain and the United States. The treaty provided that “all territory, places, and possessions whatsoever, taken by either party from the other, during the war…shall be restored without delay.” In Oregon Country, that requirement created confusion over which properties owned or developed by citizens of each nation justified the proscribed restoration.

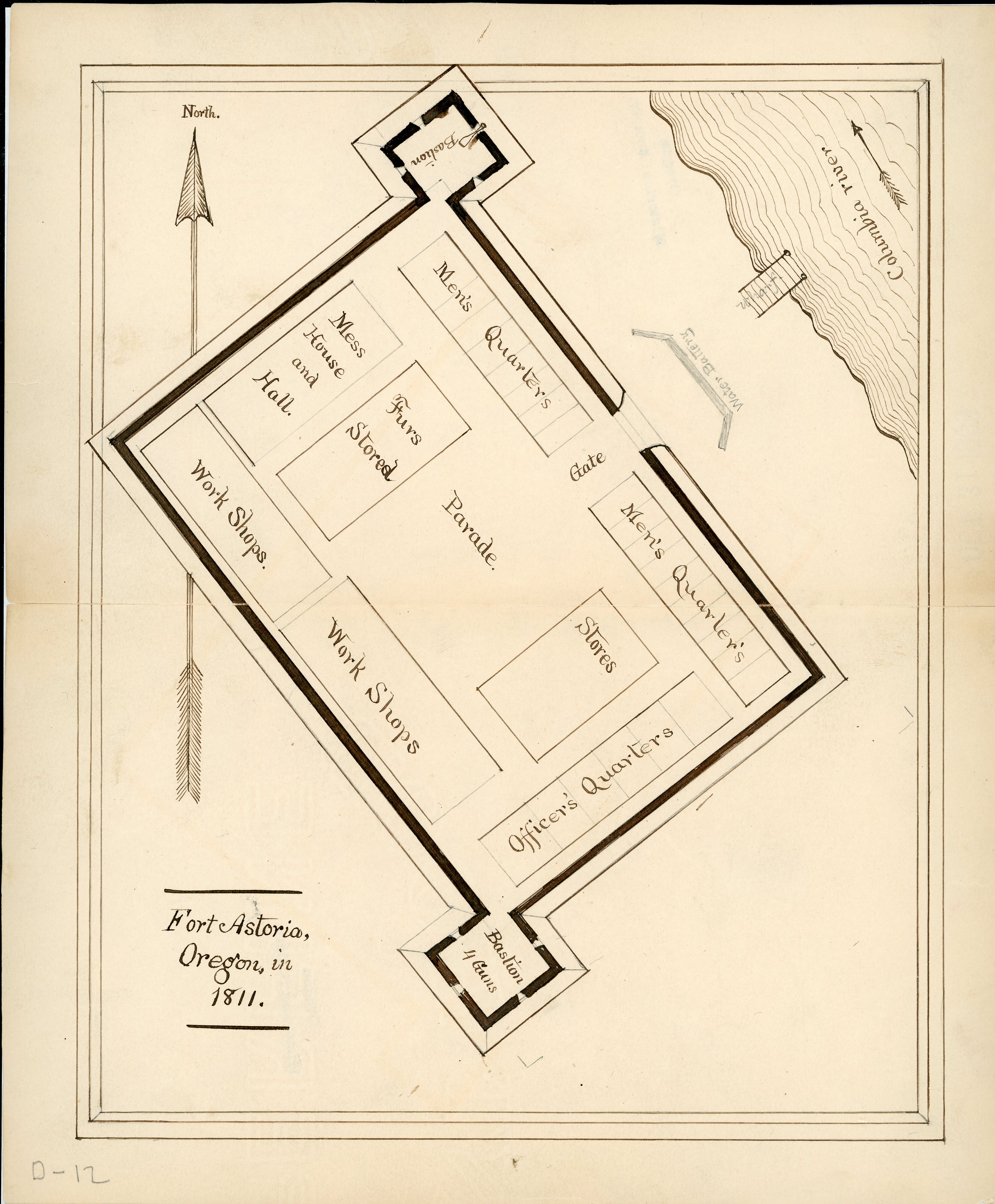

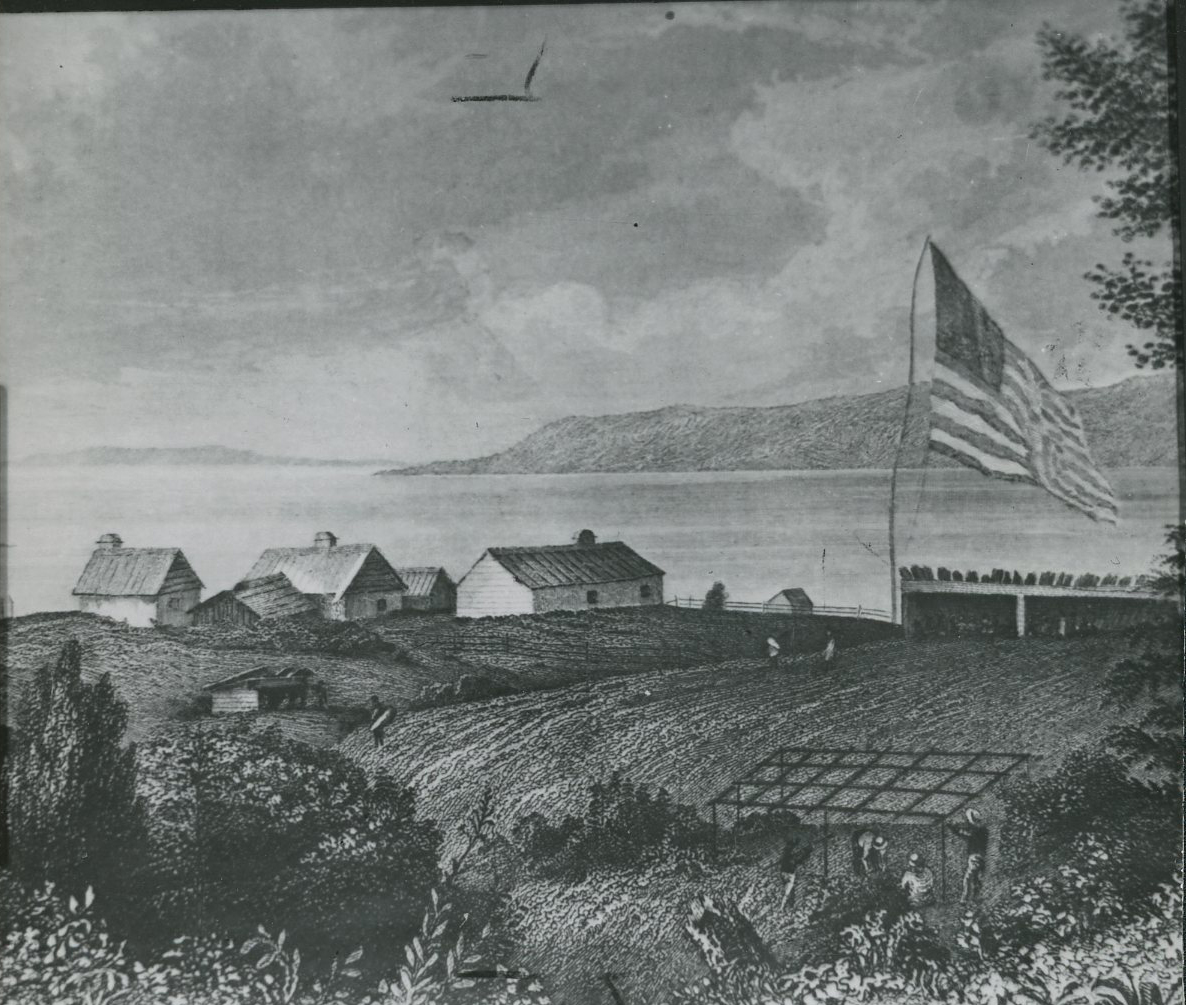

The ownership of Fort Astoria at the mouth of the Columbia River was a particular puzzle. The fort had been created in 1811 by the Pacific Fur Company, an American firm, but sold two years later to the North West Company, a British concern. Although Fort Astoria was not a spoil of war, Britain had sent a warship during the War of 1812 to seize the fort, only to find that it was already in British hands. Nonetheless, the ship’s captain ran the Union Jack up the fort’s flagpole, thereby establishing a purported post-war claim. If the fort had passed from American to British hands as a consequence of the war, the 1814 treaty suggested that it should revert to the United States. But the exchange had been between private corporate firms, so the fort fell outside the agreement’s purpose.

The issue of Astoria was unmentioned at Ghent. At the London Convention of 1818, where diplomats addressed post-war economic and political issues, the two nations considered Fort Astoria but found it a relatively minor issue. Still, they discussed the competing claims to Oregon: Britain underscored the extensive maritime exploration by George Vancouver in 1792, while the United States offered the discovery of the Columbia River by Robert Gray, also in 1792. Stymied and under little pressure to resolve the issue, the diplomats pushed off a final agreement to future discussions and agreed to a joint occupation of the Oregon Country for ten years.

The joint occupation bilateral treaty agreement provided that citizens of both nations could occupy the Oregon Country. “It is agreed,” Article III specified, “that any Country that may be claimed by either Party on the North West Coast of America, Westward of the Stony Mountains, shall, together with its Harbours, Bays, and Creeks, and the Navigation of all Rivers within the same, be free and open, for the term of ten Years from the date of the Signature of the present Convention, to the Vessels, Citizens, and Subjects of the Two Powers.”

Joint Occupation of Oregon

In application, the joint occupation agreement allowed a relatively free and open development of the region, essentially a ten-year opportunity to pursue commerce. The idea of sovereignty did not enter into the agreement.

The British acted first by expanding its fur trade interests after 1821 through the activities of the Hudson’s Bay Company. This alarmed some American officials and prompted U.S. efforts to resolve land and economic claims before the end of the agreement in 1827. Representative John Floyd of Virginia—who counted William Clark, Pacific Fur Company men, and Sen. Thomas Hart Benton (a vocal promoter of expansion) as friends—introduced legislative bills in 1821 and 1824 that advocated the establishment of an American port of entry at Astoria and the application of all national revenue laws (the levying of import duties). Floyd’s bills failed to pass, but the desire to expand the nation to Oregon remained popular among expansionists in Congress for two decades.

By 1825, British and American negotiators resumed discussions in London, aware that the joint occupation agreement had only two years to run. Britain hoped to deny the American demand that the forty-ninth parallel mark the nations’ division of territory in the Pacific Northwest by suggesting British control of Puget Sound and American ownership of minor port locations on the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Albert Gallatin, representing the United States, offered Britain navigation rights on the Columbia River as compensation for American control of all land south of the forty-ninth parallel.

Politicians in both nations rejected all proffered divisions of Oregon. On August 6, 1827, after eight months of negotiation, the diplomats settled for renewing the treaty for an indefinite term and a proviso that either nation could terminate the agreement with one year’s notice.

The ambition by political powers to control and own Oregon ignored the ownership and occupation of the region by Indigenous peoples. Native property rights would not become an issue until Americans pursued ownership of lands in the 1850s, years after the solution to the Oregon Question. From the outset of their joint occupation, however, both nations viewed Oregon as a legitimate target of their imperial ambitions, generally understood as commercial. But by the 1830s and early 1840s, American political interest in the region had begun to focus on colonization, first as an expression of expansionist politics and second as a means of overwhelming Britain’s early advantages under terms of the joint occupation agreement.

By 1842, Britain’s valuation of its investment in Oregon had waned, partly the result of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s declining fur trapping in Oregon Country and the opening of Chinese ports to British commerce, which redirected British strategic interests in the Pacific. Britain’s changing opinion coincided with a tide of American migration to the Oregon Country and a broad support for missionaries, especially Protestants, working to convert Indigenous peoples in the region, which added cultural purpose to the acquisition of the territory.

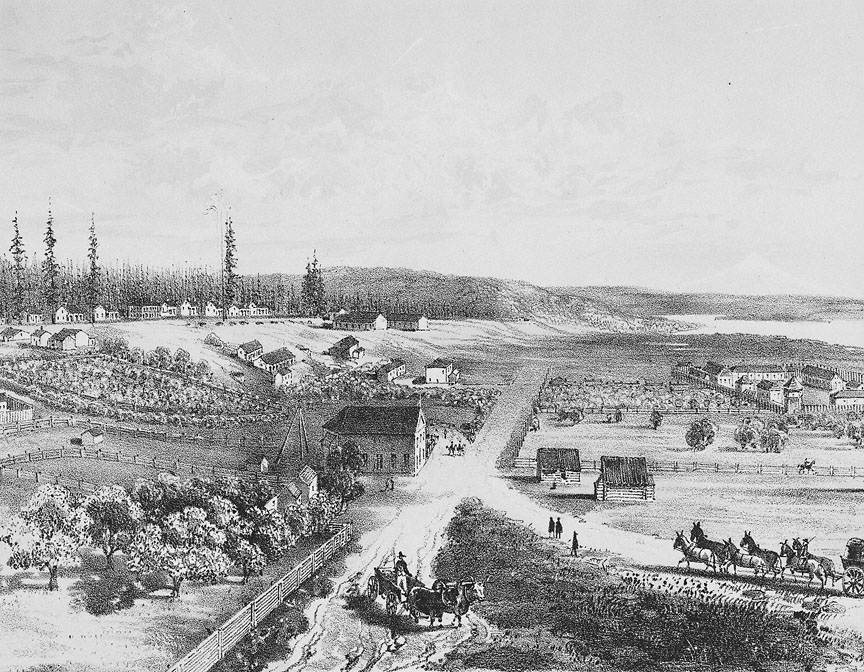

Migrants to Oregon began petitioning Congress as early as 1838, when missionary Jason Lee delivered a plea by Willamette Valley residents for protection and inducements for settlement in Oregon. In 1839, Thomas J. Farnham, who had led a group of resettlers to Oregon from Peoria, Illinois, was instrumental in compiling a petition to Congress requesting the extension of American laws to Oregon. And in 1843, Robert Shortess circulated a petition urging Congress to pass laws that would secure American rights in Oregon.

The Peoria and Shortess petitions criticized the Hudson’s Bay Company and abetted an anti-British sentiment among politically active resettlers in the Willamette Valley. Oregon Trail migrants, who came in increasing numbers after 1841, created a provisional government in 1843, a preemptive set of laws and regulations that had no standing in law and provided no economic basis of support for the proclaimed polity. “In a word,” historian Robert Loewenberg wrote, “the provisional government was utopia,” a paper state with no taxes or responsibilities to the nation. The resettlers clearly wanted the benefit of U.S. government support, but they had no political leverage, save getting politicians to take up their cause and solve the Oregon Question.

In Britain, support for acquiring Oregon had little connection to resettlement and came primarily from commercial interests who saw value in Puget Sound harbors and trade. British imperialists also supported the acquisition of Oregon, but because they tended to champion nearly any expansion of Britain’s Empire, their advocacy proved to be mercurial. On the other side of the matter, there was opposition in both nations to acquiring Oregon, especially if it involved force of arms or another war.

Nonetheless, American expansionist politicians beat a drum for Oregon. “In the campaign of 1844,” historian Norman Graebner wrote, “the Oregon issue, from its inception a diplomatic and therefore an executive problem, became a weapon in a struggle for domestic political power.” James K. Polk, the Democratic candidate for president, embraced expansion and defeated nationalist Henry Clay, the Whig candidate. Contrary to references in U.S. history textbooks, the political slogan “54-40 or Fight” (a reference to the southern boundary of Russian Alaska) was never used in the campaign, although by late 1845 it had become a popular rallying cry for expansionists. While the idea of expansion to Oregon did not decide the 1844 election, resolutions in Congress in 1843 had called for an “all of Oregon” expansion of the Republic, and some proponents offered up the 54°40' parallel as a goal. Despite some saber-rattling, the resolution of the Oregon Question came through diplomacy.

A Diplomatic Solution

The Oregon Question never faded from discussion among British and American diplomats, particularly after the first wave of resettlers migrated to the Willamette Valley over the Oregon Trail in the early 1840s. Lingering territorial disputes between Britain and the United States over the boundary between Maine and Canada harkened back to 1783 and included commercial claims between nationals of each nation. Solving those disputes and the prospect of resolving the Oregon issue prompted the two nations to convene another treaty discussion in 1842. Alexander Baring (Lord Ashburton) represented Britain, and Secretary of State Daniel Webster spoke for the United States.

The negotiations took place in Washington, D.C., beginning in April and concluding with the Webster-Ashburton Treaty in August 1842. The treaty reaffirmed the forty-ninth parallel as the U.S.-Canada border, from Lake of the Woods to the Rocky Mountains; established a permanent border between Maine and New Brunswick; and solved problems in criminal extraditions between the two countries. But the negotiations did not resolve the Oregon Question.

The British began negotiations by suggesting a division of Oregon along the Snake River that was far more beneficial to its interests than earlier proposals. Meeting resistance from Webster, the British diplomats fell back to their previous demand for the Columbia River as the international boundary. For his part, Webster ignored Britain’s suggestions and tried a new approach, suggesting a grand solution that involved cessions from Mexico. The British considered Webster’s proposal a bit fantastic and held firm on the Columbia River line. In the end, the diplomats kicked the can down the road and made no mention of Oregon in the treaty.

The Webster-Ashburton Treaty was a compromise, and though criticized as lackluster, it suggested a tempering of attitude by diplomats of both nations and an avoidance of hostilities. Polk’s election, however, energized the expansionists. Popular opinion supported the forty-ninth parallel boundary, with many expansionists demanding acquisition of territory to 54°40' N and threatening war. Both nations retreated to positions they had held in 1827. By the end of 1845, according to Merk, the Oregon Question had “relapsed into a dangerous state of diplomatic deadlock,” a situation that required attention at the highest level.

In early January 1846, the Times of London editorialized on the Oregon issue, revealing a political pivot from its earlier hawkish attitude: “That there are men in America who long for a war with Great Britain [over Oregon] is, we fear, no less true than that there are men in this country to whom a war with the United States would be by no means unwelcome. But we would fain express a hope that the statesmen of the Republic are no more amenable than the Ministers of England to the influence of the most violent or the most thoughtless among their countrymen.”

The Times concluded that the two nations “are of one family” and argued for diplomatic resolution and an end to talk of war. The editorial helped push Britain to give up its insistence on the Columbia River boundary and in effect deflated the talk of war in the United States. “The war spirit has talked itself hoarse and feeble,” Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner wrote in February 1846, “and the conscience of the nation is awakening.”

In early 1846, the political atmosphere in Britain and the U.S. had become amenable to new negotiations. Representatives began talks in London in March that quickly produced a treaty resolution to the Oregon Question. The compromise agreement extended the international boundary at the forty-ninth parallel into Puget Sound and left Vancouver Island in British hands (the international water boundary in the Sound was not resolved until 1872). The Oregon Treaty met with approval by the U.S. Senate, and plenipotentiaries signed it in Washington, D.C., on June 15, 1846, ending thirty-eight years of Anglo-American disputation.

-

![Map of Oregon Territory, 1848]()

-

![John B. Preston, General Land Office]()

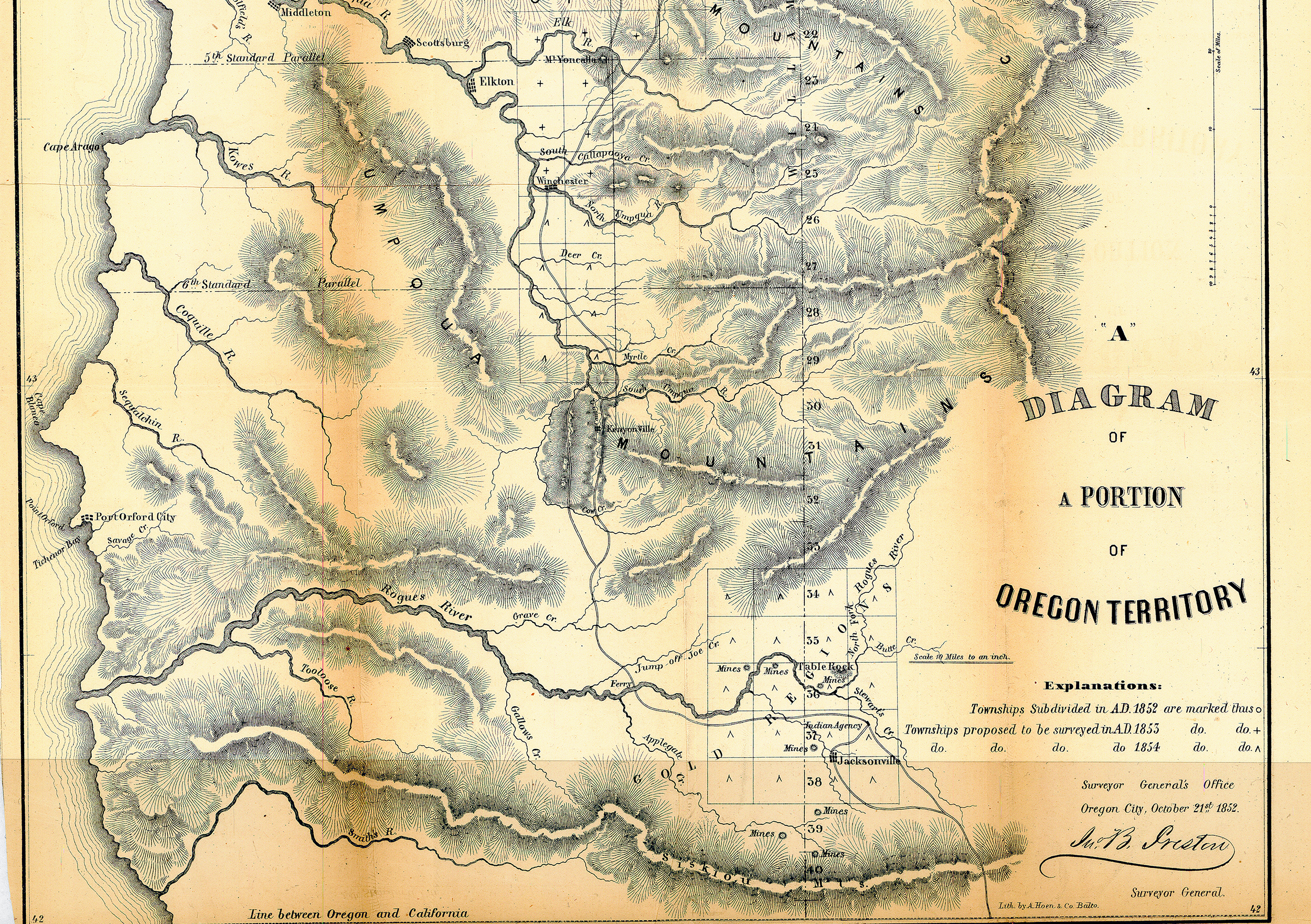

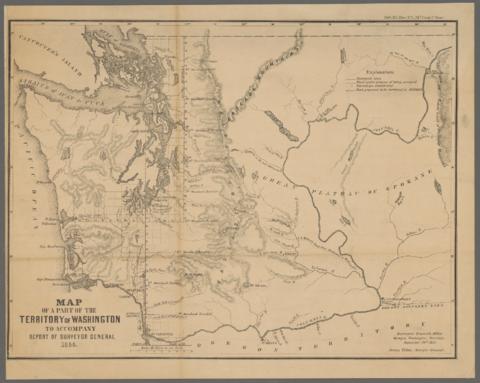

"A Diagram of a Portion of Oregon Territory," 1852.

John B. Preston, General Land Office Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb013635

-

![Note: this map was made before Oregon became a territory in 1848. The title is a general description rather than a legal designation.]()

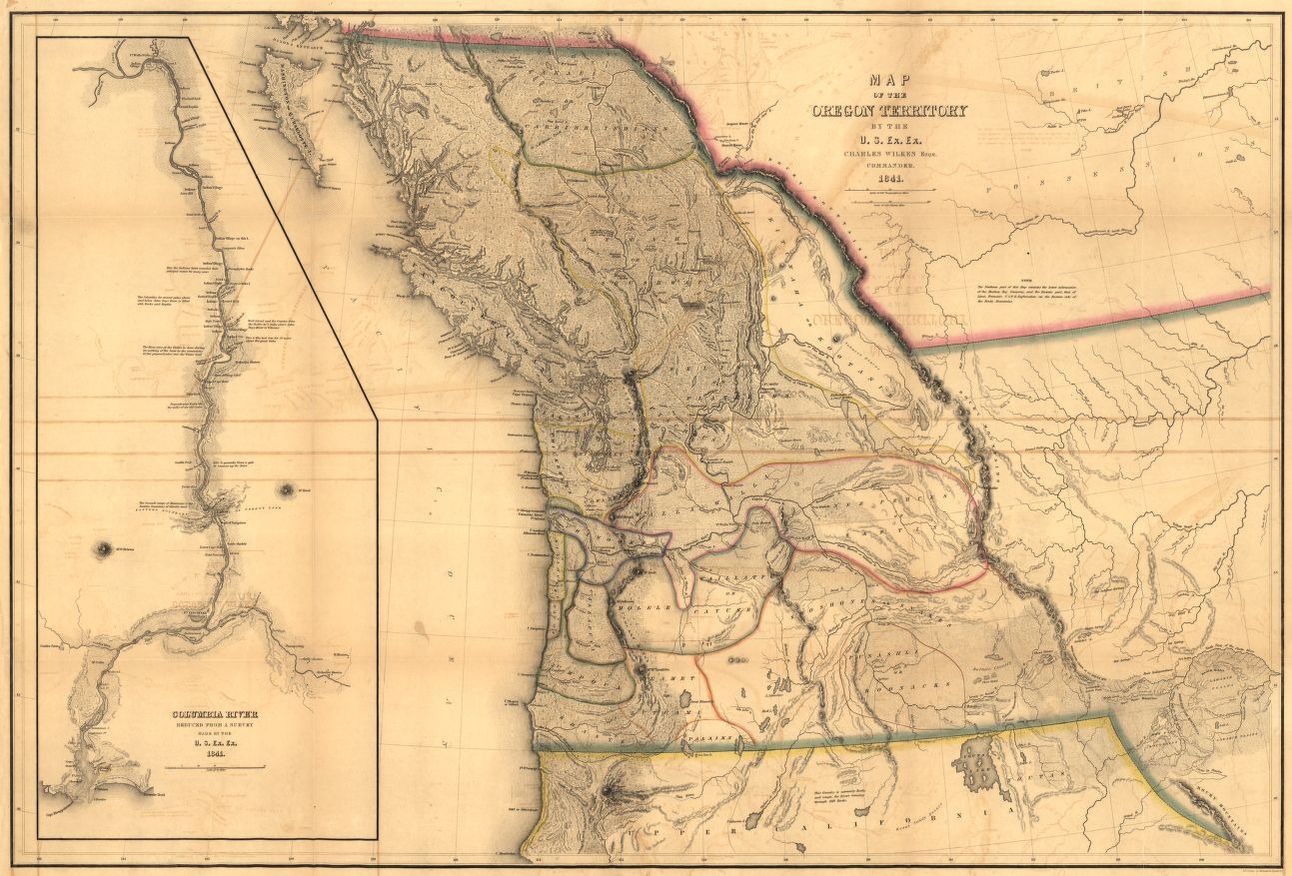

'Map of the Oregon Territory,' by Charles Wilkes and James Young, 1844.

Note: this map was made before Oregon became a territory in 1848. The title is a general description rather than a legal designation. Courtesy Library of Congress

Related Entries

-

![Astor Expedition (1810-1813)]()

Astor Expedition (1810-1813)

The Astor Expedition was a grand, two-pronged mission, involving scores…

-

![Cartography of Oregon, 1507–1848]()

Cartography of Oregon, 1507–1848

The cartographic history of Oregon as a place in the Pacific Northwest …

-

![Creation of Washington Territory, 1853]()

Creation of Washington Territory, 1853

On August 14, 1848, Congress created Oregon Territory, a vast stretch o…

-

![Fort George (Fort Astoria)]()

Fort George (Fort Astoria)

Fort George was the British name for Fort Astoria, the fur post establi…

-

![Fur Trade in Oregon Country]()

Fur Trade in Oregon Country

The fur trade was the earliest and longest-enduring economic enterprise…

-

![George Vancouver (1757-1798)]()

George Vancouver (1757-1798)

The role George Vancouver played in Oregon history is tangential, yet i…

-

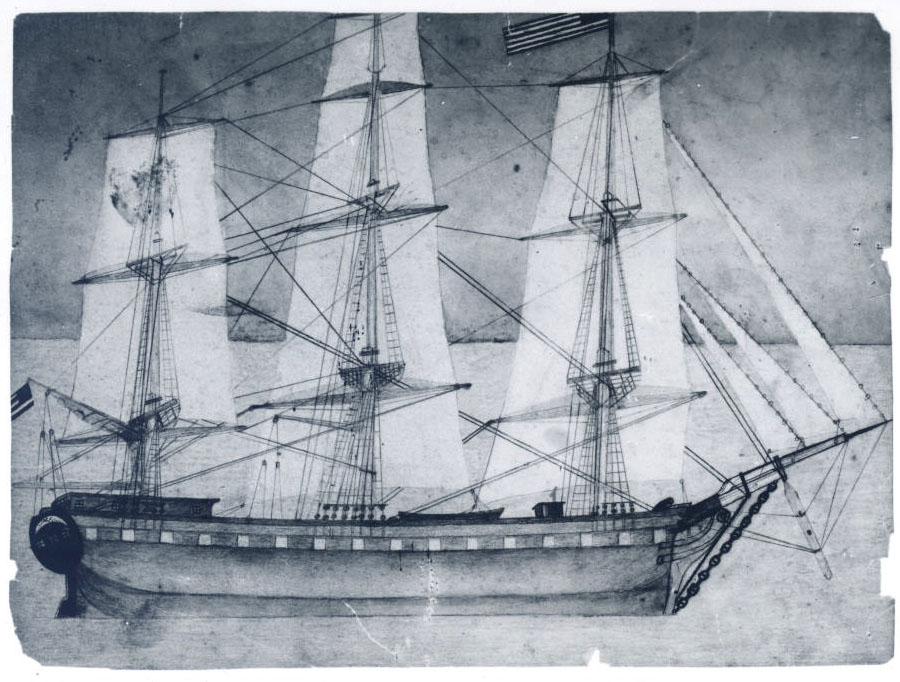

![Great Reinforcement (1840)]()

Great Reinforcement (1840)

One of the signal immigrations to Oregon came by sea in 1840, years bef…

-

![Hudson's Bay Company]()

Hudson's Bay Company

Although a late arrival to the Oregon Country fur trade, for nearly two…

-

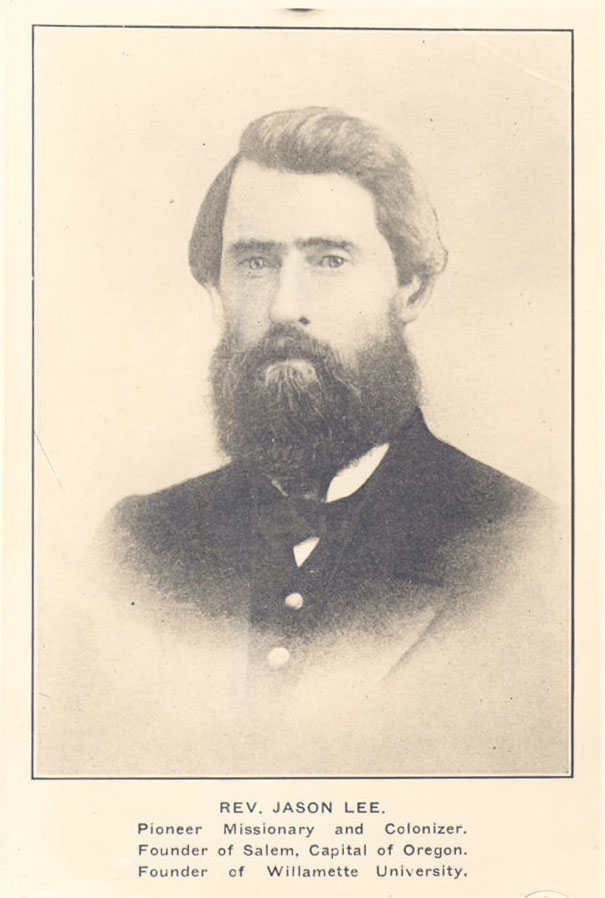

![Jason Lee (1803-1845)]()

Jason Lee (1803-1845)

Few names in the history of early nineteenth-century Oregon are better …

-

![John Floyd (1783–1837)]()

John Floyd (1783–1837)

During his service in the U.S. House of Representatives, John Floyd of …

-

![Provisional Government]()

Provisional Government

The Provisional Government, created in May-July 1843, was the first gov…

-

![Robert Gray (1755–1806)]()

Robert Gray (1755–1806)

On May 11, 1792, Robert Gray, the first American to circumnavigate the …

-

![Thomas Hart Benton and Oregon]()

Thomas Hart Benton and Oregon

As a newspaper editor and then as a United States senator for Missouri …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Ambler, Charles H. “The Oregon Country, 1810-1830: A Chapter in Territorial Expansion.” Mississippi Valley Historical Review 30 (June 1943): 3-24.

“British-American Diplomacy: Convention of 1818 between the United States and Great Britain.” http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/conv1818.asp.

Graebner, Norman A. Empire on the Pacific: A Study in American Continental Expansion. New York: Ronald Press, 1955.

Loewenberg, Robert. Equality on the Oregon Frontier. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1976.

Merk, Frederick. “British Party Politics and the Oregon Treaty.” American Historical Review (July 1932): 653-77.

_____. “The Genesis of the Oregon Question.” Mississippi Valley Historical Review (March 1950): 583-612.

_____. “The Ghost River Caledonia in the Oregon Negotiation of 1818.” American Historical Review (April 1950): 530-51.

_____. The Oregon Question: Essays in Anglo-American Diplomacy and Politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967.

Miles, Edwin A. “‘Fifty-four Forty or Fight’—An American Political Legend.” Mississippi Valley Historical Review (September 1957): 291-304.

Pletcher, David. The Diplomacy of Annexation. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1973.

Schroeder, John H. “Rep. John Floyd, 1817-1829: Harbinger of Oregon Territory.” Oregon Historical Quarterly (1969): 339-41.