First organized in 1779 by a small group of Canadian fur traders based in Montreal, the North West Company dominated the North American fur trade west of the Rocky Mountains from 1813 to 1821, outpacing the Hudson’s Bay Company west across the Rocky Mountains to the Columbia River and supplanting the Pacific Fur Company in the Oregon Country. Ambitious in its global trade aspirations, the North West Company leveraged a decentralized structure, made efficient through short-term agreements with merchants, supply houses, and economically empowered field officers. A failure to establish direct trade with China and other challenges, however, limited the company’s opportunity for profit, and the North West Company merged with the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1821.

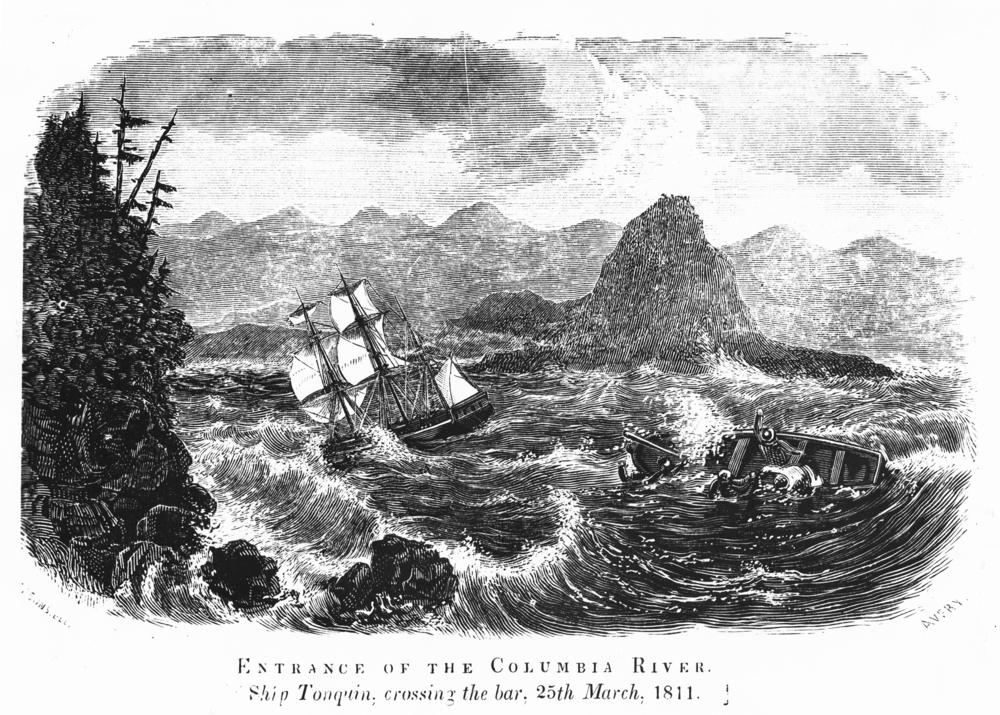

North West Company trader, explorer, and surveyor David Thompson reached the upper Columbia River in 1807, eager to outdistance the Hudson’s Bay Company and partner with the American traders who were inspired by the reports of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. He established Kootenae House as the first fur trading post in the Columbia River basin. Subsequent ventures into the region established additional posts, including Kullyspell House, Saleesh House, Fort Kootenay in 1809, and Spokane House in 1810. In 1811, when Thompson explored the lower Columbia from Kettle Falls “to open out a Passage for the Interiour Trade with the Pacific Ocean,” he encountered John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company at Fort Astoria. The partnership failed to materialize, so for two years the rivals would scratch out a wary coexistence in the Oregon Country, competing directly and cooperating occasionally.

With the War of 1812 threatening the British seizure of American assets, the North West Company’s John George McTavish arrived at Fort Astoria with an offer to purchase all Pacific Fur Company holdings. In October 1813, Pacific Fur Company partners at the fort agreed to sell “all establishments, furs, and stock” in the Pacific Northwest to the North West Company. Many Pacific Fur Company employees became Nor’Westers.

Subsequently, Fort George (the North West Company’s renamed Fort Astoria) became the company’s headquarters and depot for the Columbia Department, which was expanded to include Willamette Post (1813) in the Willamette Valley and the Pacific Fur Company’s Fort Okanagan. The North West Company then employed the Pacific Fur Company’s system of supplying upriver posts with annual trade goods and necessities ("the outfit") and sending the annual collection of trapped and traded furs ("the returns") to Fort George and then to London. The route between Fort George and Fort St. James, known as the Columbia Brigade Route, linked with the Fort William Brigade Route at Fort McLeod, thereby connecting the Oregon Country to Montreal. Plans to connect directly to markets in Canton, China, never came to fruition.

Despite the absence of competition, the North West Company “fell greatly short” of financial expectations. Reasons included the inability to connect directly to markets in Canton due to East India Company control, conflict with Native people resulting in loss of furs, and what company officer Alexander Ross called “apathy and want of energy” and “extravagance” involving imported goods and provisions. The agricultural potential of the Willamette Valley also tempted Nor’Westers away from company employ. Reorganization in 1815 did little to increase the company’s success, but it did initiate the employ of seasonal trapping parties—called brigades—that traveled into the Willamette and Umpqua River Valleys and to California and the Snake River Country in search of furs.

In 1818, the establishment of Fort Nez Perce signaled the commitment of the North West Company to trap in the Snake River region, which HBC later embraced as a "fur desert" policy that aimed to trap out the furs and thereby deter American interest west of the Rocky Mountains. Snake Country expeditions after 1821 trekked the harsh winter landscape of present-day eastern Oregon, Idaho, and Nevada for nearly thirty years, trapping out fur-bearing animals at a furious pace.

One result of the North West Company’s quest for profit was a diverse workforce. French Canadians made up the majority of the company's employees. In addition, not only did the company continue the Pacific Fur Company’s practice of hiring native Hawaiians, but it also employed Canadian Iroquois to serve “in the double capacity of canoe-men and trappers” throughout the region. In 1819, North West Company personnel named the Owyhee River after two Hawaiian trappers who were killed there by Indians.

After years of conflict, the North West Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company merged in 1821. Key to the merger was the North West Company’s John McLoughlin, who organized the company’s recalcitrant wintering partners in 1819 and opened secret talks with the HBC. The new Hudson’s Bay Company adopted the North West Company’s efficient field organization, including employing a governor to serve as an administrative middleman between field officers and a governing committee and creating classes of officers (chief factors and chief traders) who earned shares of the company’s annual gains. Several Nor’Westers, including McLoughlin and Peter Skene Ogden, became prominent HBC employees.

Two former North West Company employees later wrote popular narratives of the early fur trade that helped bring Oregon to new audiences in North America and abroad: Adventures on the Columbia, by Ross Cox (1831), and The Fur Hunters of the Far West: A Narrative of Adventures in the Oregon and Rocky Mountains, by Alexander Ross (1855).

-

![Sketch by H. Warre]()

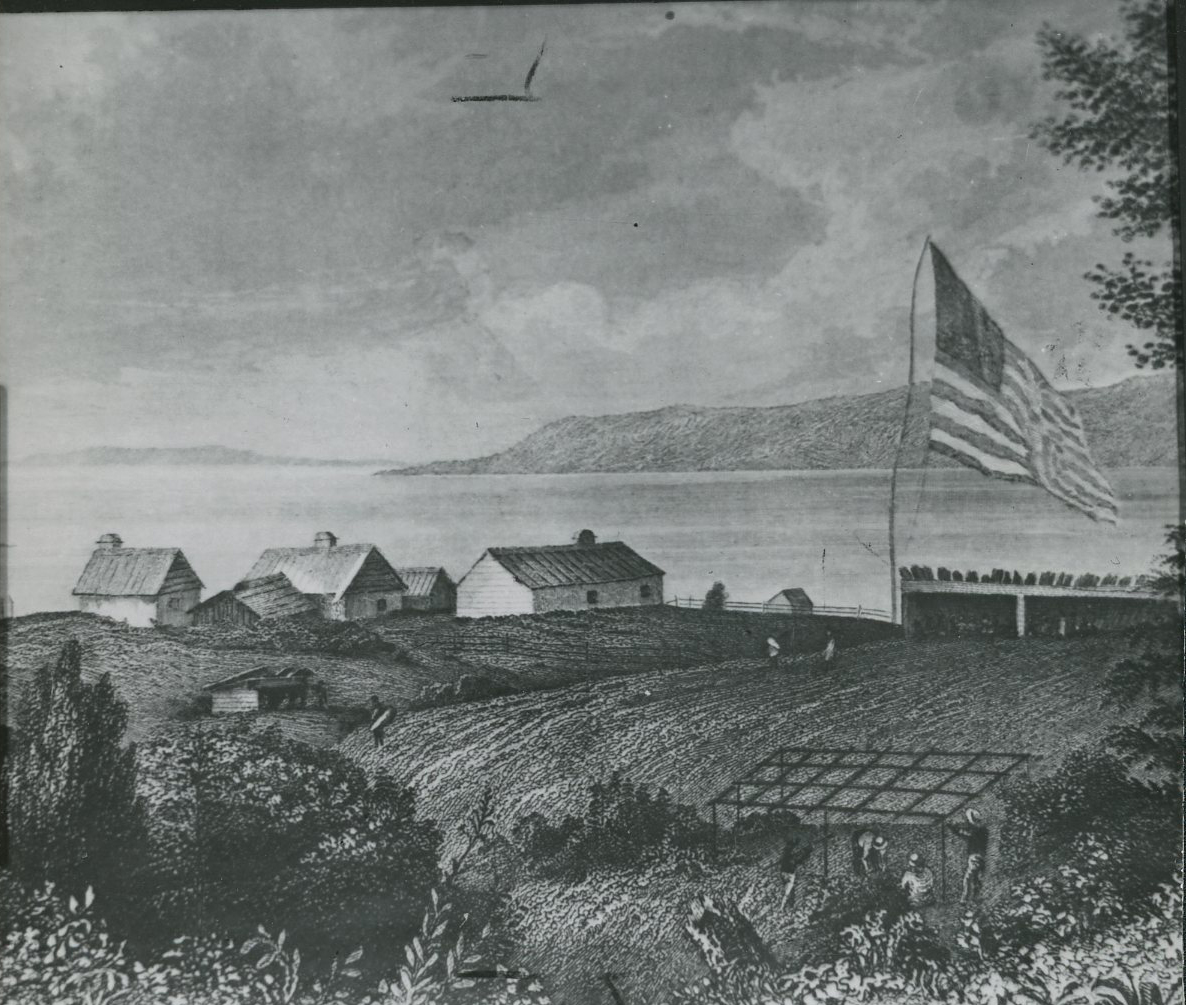

Fort George, 1845.

Sketch by H. Warre Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, 35111

-

![]()

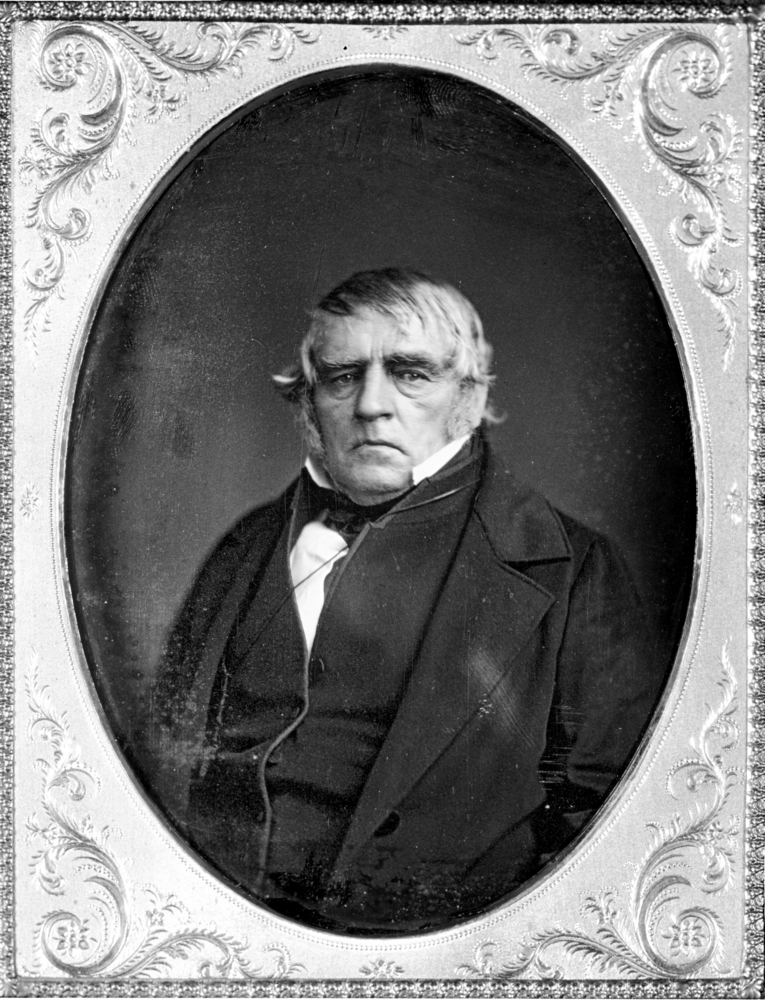

Alexander Ross.

Archives of Manitoba, Ross, Alexander 4 (N21467)

Related Entries

-

![Alexander Ross (1782-1856)]()

Alexander Ross (1782-1856)

Born in the Scottish Highlands, schoolteacher Alexander Ross immigrated…

-

![David Thompson (1770-1857)]()

David Thompson (1770-1857)

British fur agent, surveyor, explorer, and cartographer David Thompson …

-

![Fort George (Fort Astoria)]()

Fort George (Fort Astoria)

Fort George was the British name for Fort Astoria, the fur post establi…

-

![Fur Trade in Oregon Country]()

Fur Trade in Oregon Country

The fur trade was the earliest and longest-enduring economic enterprise…

-

![Hudson's Bay Company]()

Hudson's Bay Company

Although a late arrival to the Oregon Country fur trade, for nearly two…

-

![John McLoughlin (1784-1857)]()

John McLoughlin (1784-1857)

One of the most powerful and polarizing people in Oregon history, John …

-

![Pacific Fur Company]()

Pacific Fur Company

The Pacific Fur Company, employee Alexander Ross wrote in 1849, was “an…

-

![Peter Skene Ogden (1790-1854)]()

Peter Skene Ogden (1790-1854)

More than any other figure during the years of the Pacific Northwest's …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Cox, Ross. The Columbia River. Edited and with an introduction by Edgar I. Stewart and Jane R. Stewart. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1957.

Franchère, Gabriel. Adventure at Astoria, 1810-1814. Translated and edited by Hoyt C. Franchere. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1967.

Gibson, James R. Lifeline of the Oregon Country. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1997.

Keith, Lloyd and John Jackson. The Fur Trade Gamble: North West Company on the Pacific Slope Pullman: Washington State University Press, 2016.

Mackie, Richard Somerset. Trading Beyond the Mountains. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1997.

McArthur, Lewis A., and Lewis L. McArthur. Oregon Geographic Names. 7th ed. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 2003.

Nisbet, Jack. Sources of the River. Seattle: Sasquatch Books, 1994.

Ronda, James P. Astoria & Empire. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990.

Thompson, David. Columbia Journals. Edited by Barbara Belyea. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2007.