Firebrand. Activist. A modest man. Ron Herndon has been described as all three. A long-time activist for minority rights and educational opportunities, especially in Portland, he was a founder of the Portland chapter of the Black United Front, the director of Albina Head Start, and the president of the National Head Start Association.

Born on December 18, 1945, in Coffeyville, Kansas, Ronald D. Herndon was reared by his grandparents, who emphasized the importance of education. In the small, segregated community of his home town, Blacks helped one another. “I saw this effort to bring about change,” he recalled. “All the adults pushed you to do well in school, despite obstacles.” A basketball scholarship helped Herndon through junior college, and in 1965 he entered Volunteers in Service to America, working as a community organizer in Michigan, New Jersey, and New York.

A Rockefeller scholarship to Reed College took Herndon to Portland in 1968. Reed was “just as racist as any institution I had encountered in my previous twenty-three years,” he said, and he spent his two years there “in protest, constant protest.” He and other members of the Black Student Union, for example, demanded that Reed establish a Black studies program, and students occupied a floor of the administration building in December 1968. By the following spring, Reed administrators and faculty had agreed to establish a Black Studies Center.

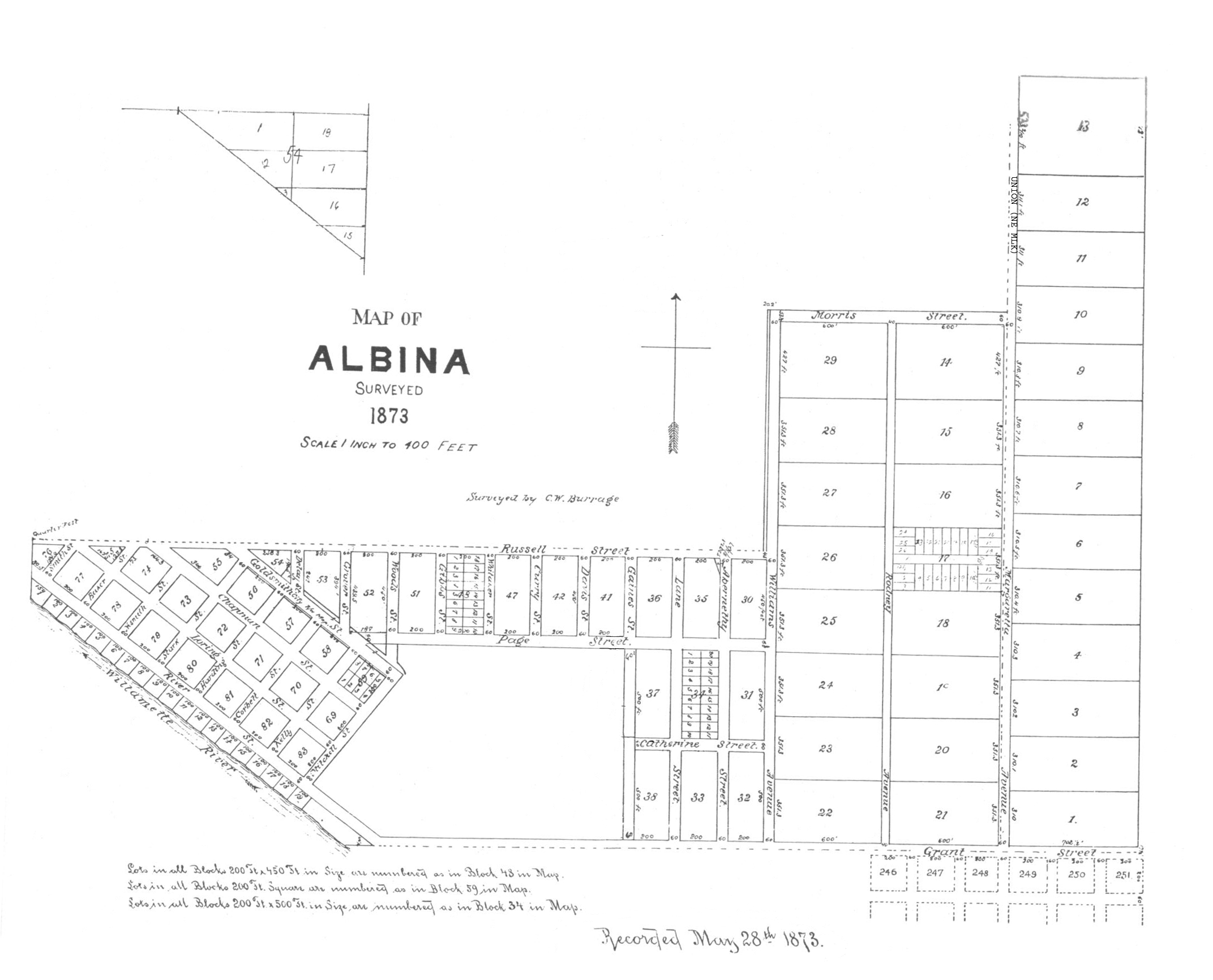

After Herndon graduated from Reed with a degree in history in 1970, he and fellow Reedies Joyce Harris and Frank Wilson co-founded the Black Educational Center, a private school on Northeast Morris Street designed to serve the academic and cultural needs of Black children. BEC grew from a summer program to a full-time school, offering kindergarten through fifth-grade instruction. It closed in the late 1990s.

In 1975, Herndon was named director of the Albina Ministerial Alliance Head Start Program. Under his leadership, Albina Head Start expanded from serving 126 children and families in 1975 to over 1,000 at twenty-five sites in 2020. The program became a “single-purpose Head Start grantee with a community-based board of directors” in 1993; it began serving families with infants and toddlers in 2000. Herndon also created a program that trains substitute teachers, many of them parents of Head Start children and employees of the program. Herndon built on his local success by serving as president and board chair of the National Head Start Association from 1991 to 2013.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Portland school district established busing policies to achieve desegregation in the schools. The unfortunate result was that about two-thirds of the students bused were Black. Black students from the King School area, for example, were bused to forty-two different schools, “effectively desegregated, perhaps,” the July 3, 1979, Oregonian reported, “but unfairly isolated.”

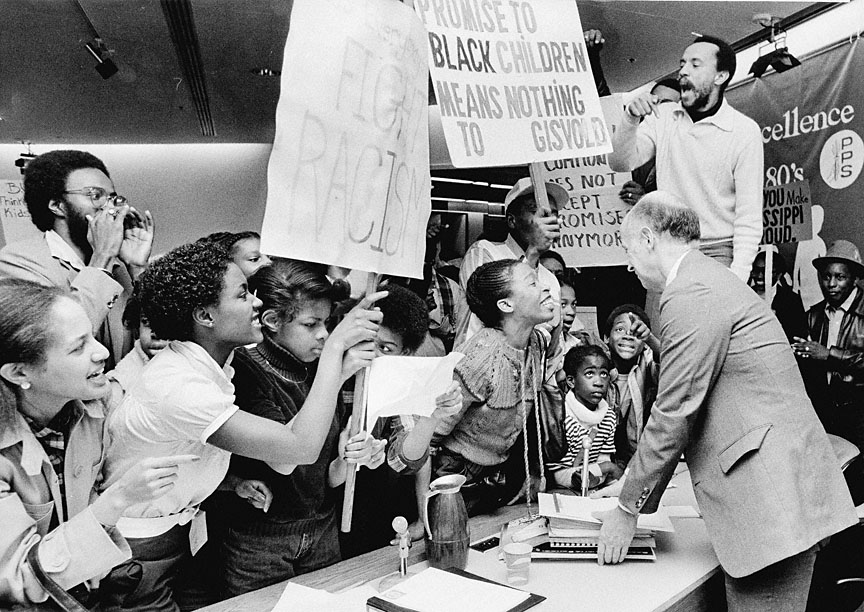

In 1978, Herndon and Rev. John Jackson, the pastor of Mt. Olivet Baptist Church, organized the Portland chapter of the Black United Front to force the school board to change its racist busing policies. The next year, an administrative ruling by the Office of Civil Rights in the Department of Health, Education and Welfare concluded that Portland’s busing program did not constitute illegal discrimination. The BUF called for a boycott of schools and the dismissal of the district superintendent. In 1980, the BUF and other concerned community members negotiated a seven-point plan for desegregation, which included an end to busing to achieve desegregation.

Over four years, the October 9, 1984, Oregonian reported, Herndon and the BUF “amassed a formidable array of accomplishments." They advocated for improved minority hiring, a Black consultant to revise curriculum (1981), the relocation of Harriet Tubman Middle School to Eliot School, near Memorial Coliseum (1982), and the hiring of Matthew W. Prophet, the city’s first Black school superintendent (1982).

The BUF also advocated for economic opportunity for Black Portlanders. Herndon approached Nike, for example, about opening a store in northeast Portland, arguing in a Willamette Week interview that “pimping the styles popularized by black kids and black athletes was too much of a one-way deal.” Nike opened a store on Northeast Martin Luther King Boulevard in 1984. It was the company’s first “community store,” where 80 percent of the workers lived within five miles and a portion of the profits was dedicated to local organizations. Nike closed the store permanently in 2023, citing concerns about safety and security.

Herndon’s 1984 partnership with Nike co-founder Phil Knight led eventually to Knight’s contributions, in the early 2020s, of more than $20 million for the purchase and upgrade of at least six buildings in North, Northeast and Southeast Portland for Albina Head Start’s childcare and preschools. In 2025, Herndon said that the funding “solidifies our ability to maintain services going forward in a very uncertain funding environment.”

Herndon remains engaged in issues that affect Black and low-income communities and is a respected spokesperson on current issues. During the Covid pandemic, for example, he and others advocated for a free test site in Portland's Black community. And he spoke out against the nights of violent protest in the city after the murder of George Floyd in 2020, reminding people that those protesters “did not represent the Black Lives Matter movement.” They had “nothing to do with helping Black people,” he told the Skanner.

Herndon received the Gladys McCoy Award in 2016 for “outstanding lifetime volunteer service dedicated to improving the [Multnomah] county community.” Each year, the Black United Fund awards the Ron Herndon Scholarship to help students “pursue higher education at the accredited college or university of their choice.” He also received the First Citizen Award from the Portland Metropolitan Association of Realtors in 2019, and in 2021 he was awarded an honorary degree from Portland State University “to acknowledge individuals who have…performed distinguished public service during their lifetime.” In 2023, an apartment building on NE Alberta Street, part of the Alberta Alive affordable housing complex, was named in Herndon's honor.

-

![]()

Ron Herndon.

Courtesy Black United Fund of Oregon -

![]()

Ron Herndon, standing, protests the PPS Board, 1982.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, OrHi 95005

Related Entries

-

Albina area (Portland)

By the late 1880s, Albina, located across the Willamette River from Por…

-

![Black Panthers in Portland]()

Black Panthers in Portland

The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense (BPP) was founded in October 1…

-

![Black People in Oregon]()

Black People in Oregon

Periodically, newspaper or magazine articles appear proclaiming amazeme…

-

![Gladys McCoy (1928–1993)]()

Gladys McCoy (1928–1993)

Gladys Sims McCoy was one of the first person of color elected to publi…

-

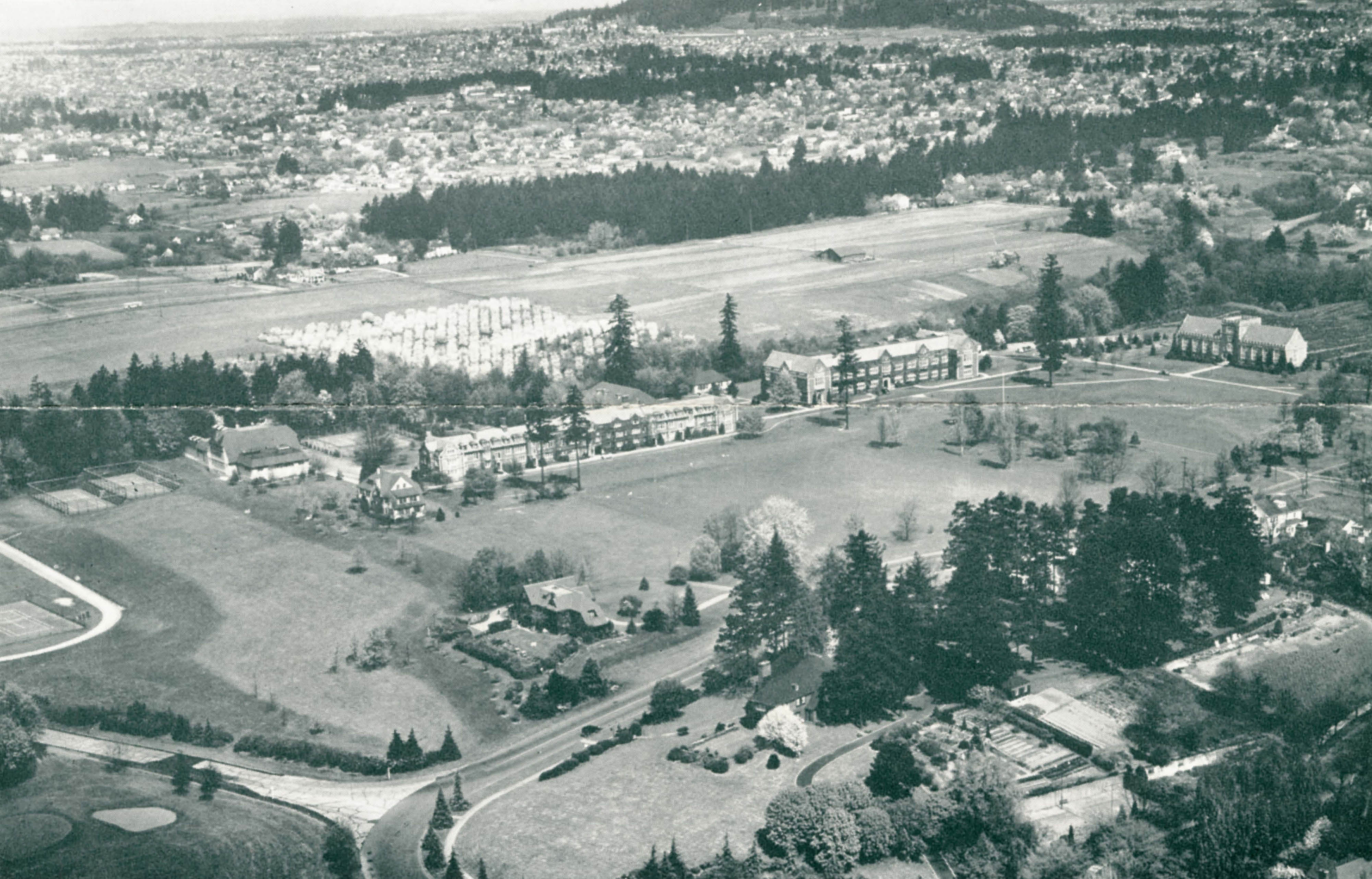

![Reed College]()

Reed College

Situated on 116 acres in southeast Portland, Reed College enrolls nearl…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

“Activist Herndon mulls campaign for governor.” Portland Oregonian, July 5, 1985, B8.

“Harsh discipline asked in T-shirt incident.” Portland Oregonian, April 30, 1985, B1.

"Lifetime Achievement: Herndon receives First Citizen honor." Portland Observer, April 24, 2019.

Feinberg, Paul. "Ron Herndon: The Head Start Activist." UCLA Anderson Blog, February 9, 2016.

"How One Head Start Trailblazer Fought against Racial Inequality." Medium, February 27, 2019.

White, Martin. "The Black Studies Controversy at Reed College, 1968-1970." Oregon Historical Quarterly 119.1 (Spring 2018): 6-37.

Jaquiss, Nigel. "The Firebrand: Ron Herndon." Willamette Week, November 9, 2004.

Johnson, Ethan, and Felicia Williams. "Desegregation and Multiculturalism in the Portland Public Schools." Oregon Historical Quarterly 111.1 (Fall 2010): 6-37.

“Minorities Find Education Is Key to Political Power." Portland Oregonian, October 9, 1984, B2.