The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense (BPP) was founded in October 1966 in Oakland, California, by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, two young Black men who met at Merritt Junior College. The party was their response to centuries of disenfranchisement of Black people in America and routine police violence in local Black neighborhoods. The BPP’s ten-point platform lists their goals of equality in the realms of employment, housing, and education, along with freedom for political prisoners and an end to police brutality.

In April 1968, when Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, Black people across the nation took to the streets in grief and anger. In Portland, where the public disturbance was minor compared to the riots in Chicago and other cities, about twenty disillusioned young Black people began meeting to study the writings of Malcolm X and the Little Red Book of quotations from China’s chairman Mao Tse-Tung.

In June 1969, one of the members of the study group was beaten and jailed. Upon his release on bail, Kent Ford held a press conference on the steps of the Portland police station at Southwest Third and Oak. “If they keep coming in with these fascist tactics,” he announced, “we´re going to defend ourselves.” With this public pronouncement, members of the original group, now down to about half a dozen, retooled themselves as a chapter of the BPP. Technically, no chapter could be founded without the blessing of Huey Newton, and Ford traveled to California later that year to secure official approval. The chapter opened an office on the southeast corner of Northeast Cook Street and Union Avenue (present-day Martin Luther King Boulevard), the first of four locations.

By the end of that year, the Portland Panthers had started a Children´s Breakfast Program at Highland United Church of Christ—where they fed up to 125 children each morning before school—as well as the Fred Hampton Memorial People´s Health Clinic, extending free medical care five evenings a week at 109 North Russell to anyone of any race. In February 1970, the BPP opened a dental clinic at 2341 North Williams. When their medical clinic was condemned and razed to accommodate a planned expansion of Emanuel Hospital, the chapter moved their Monday and Tuesday night dental practice to the Kaiser dental clinic at 214 N Russell and their medical clinic to the former dental clinic space on North Williams.

“It felt good,” Oscar Johnson recalls. “We were doing something. We had the respect of the community.” New members were attracted to the social programs, and the Portland chapter grew, though it never exceeded fifty members, about a third of whom were women. Original members included Johnson, a former U.S. Marine; Percy Hampton, who joined while still at Jefferson High School; Tommy Mills, a decorated Vietnam War vet; Joyce Radford, who volunteered for the medical clinic; Sandra Ford, whose work at the medical clinic launched her in a new career; and Kent Ford, captain of the Portland chapter, who had turned down a college scholarship in order to support his mother and siblings in Richmond, California. At the time of Ford's much-publicized arrest, he was running a crew that sold candy door-to-door and sending money home.

Meanwhile, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover declared the BPP a threat to national security. In August 1967, he issued an internal memorandum directing the FBI´s counter-intelligence program to “expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit or otherwise neutralize” the party. The result nationally was the assassination or incarceration of many party members, including Fred Hampton and Geronimo Pratt. Many former Panthers remain in prison or exile today.

Despite the persecution, BPP chapters—forty to forty-five of them—sprang up in major cities across the nation, including one that opened in Eugene, Oregon, in 1968 and operated for over a year. Portland BPP members were tracked by the FBI and characterized by the two major newspapers as criminal; yet they were spared the violent attacks party members suffered in other cities, perhaps because so many local dentists, doctors, and nurses—nearly all of them white—helped with their social programs. George Barton, a neurosurgeon, was their first volunteer physician, and Gerry Morrell was their first volunteer dentist. As head of Community Outreach for the Multnomah Dental Society, Morrell persuaded many others to join him.

The Portland chapter lasted a decade, finally closing the medical clinic in 1979. “We decided we just couldn´t keep going,” says Sandra Ford, a founding member who worked in the health clinic as a medical assistant. Those who volunteered in the social programs remember their work with pride, and former Portland Panthers are still stopped on the street by children whom they fed in the breakfast program.

-

![Fred Hampton People's Free Health Clinic on N. Russell St., Portland.]()

Fred Hampton People's Free Health Clinic.

Fred Hampton People's Free Health Clinic on N. Russell St., Portland. Courtesy Lewis & Clark College

-

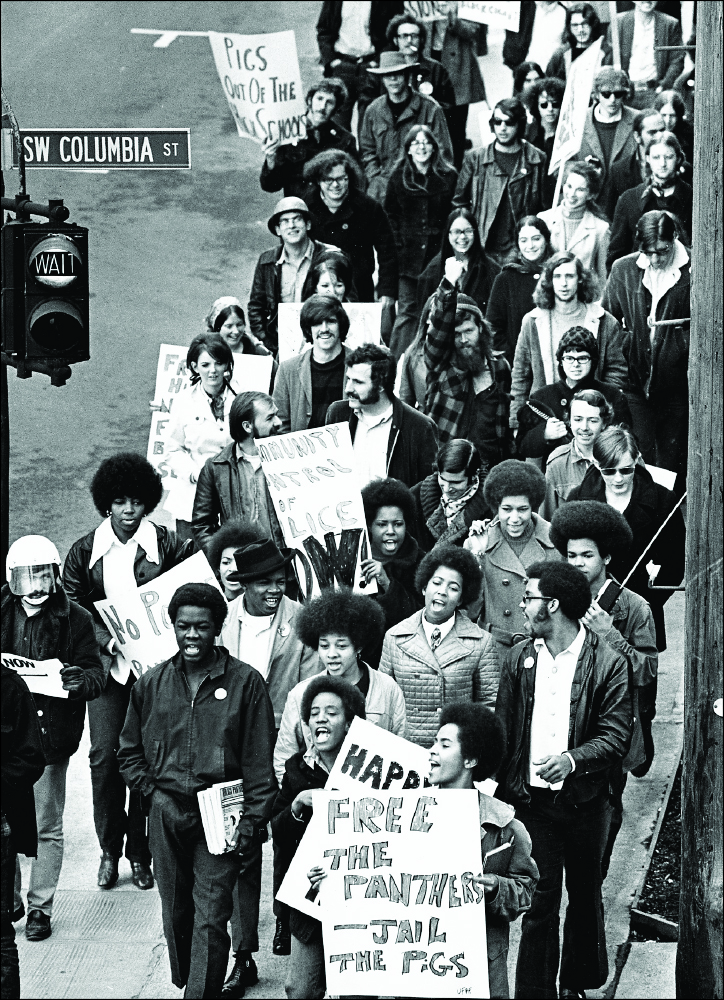

![]()

Demonstration calling for police reform, 1970, in downtown Portland.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, Oregonian, bb007217

-

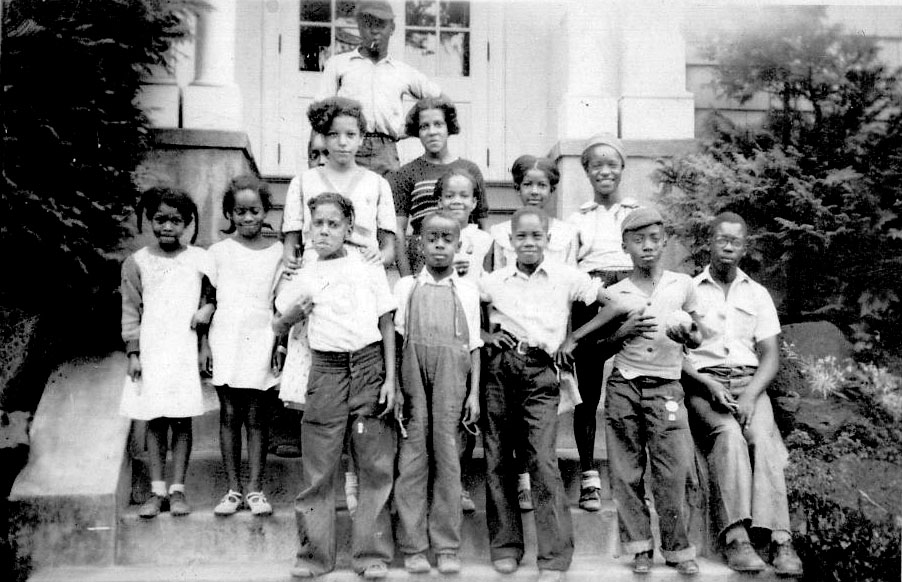

![Children at the Black Panthers' free breakfast program, 1971. Kent Ford sits with the children.]()

Children at the Black Panthers' free breakfast program, 1971.

Children at the Black Panthers' free breakfast program, 1971. Kent Ford sits with the children. Courtesy Portland Oregonian

Related Entries

-

![Beatrice Morrow Cannady (1889–1974)]()

Beatrice Morrow Cannady (1889–1974)

Beatrice Morrow Cannady was the most noted civil rights activist in ear…

-

![Black People in Oregon]()

Black People in Oregon

Periodically, newspaper or magazine articles appear proclaiming amazeme…

-

![DeNorval Unthank (1899-1977)]()

DeNorval Unthank (1899-1977)

In 1929, Portland was a city deeply divided. Its small population of Af…

-

![Edwin C. (Bill) Berry (1910–1987)]()

Edwin C. (Bill) Berry (1910–1987)

Bill Berry, a leader in the Urban League for nearly thirty years, was t…

-

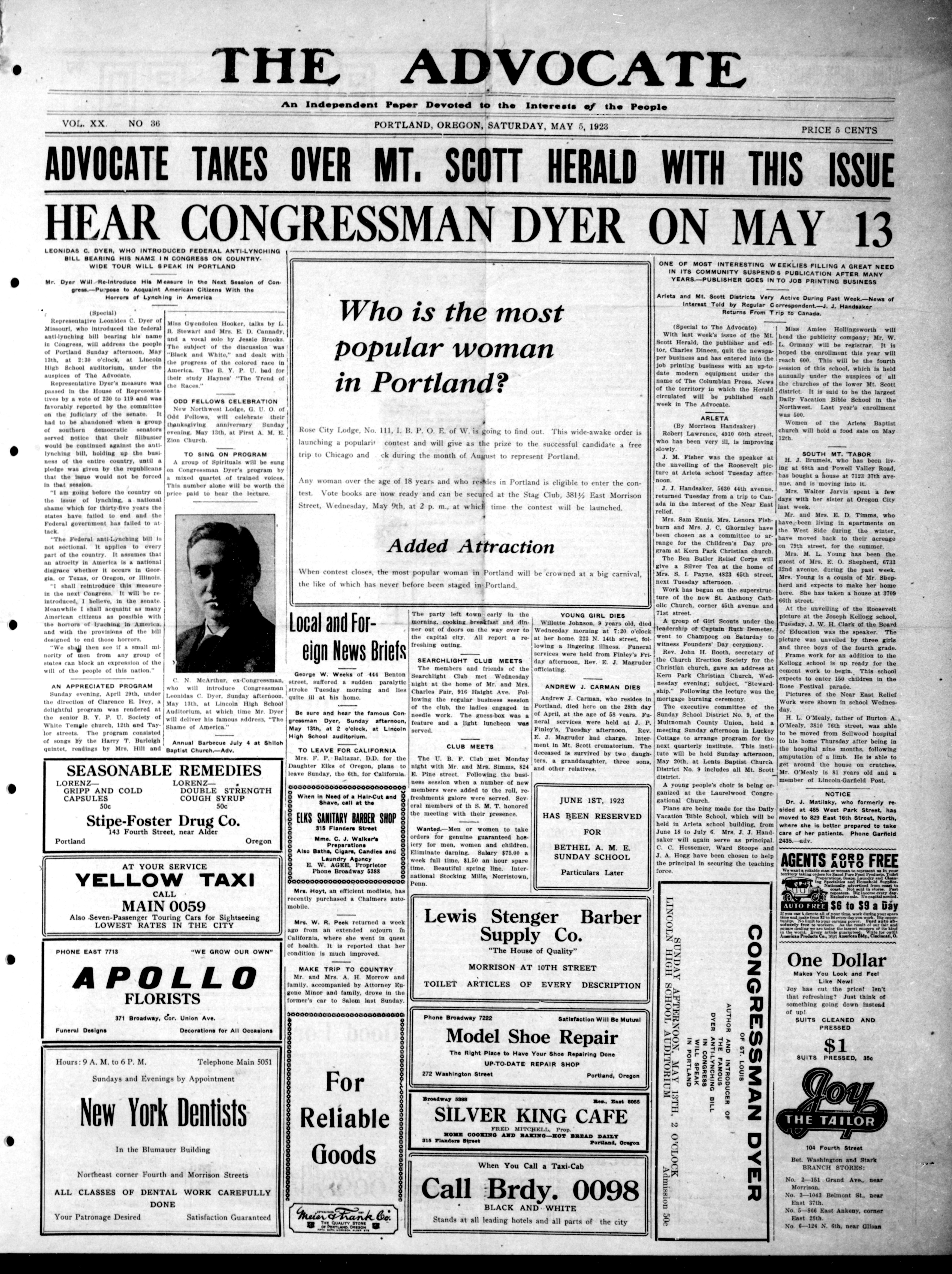

![The Advocate]()

The Advocate

From 1903 until about 1938, the Advocate recorded incidents of racism a…

-

![Vancouver Avenue First Baptist Church]()

Vancouver Avenue First Baptist Church

The history of the Vancouver Avenue First Baptist Church of Portland is…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Bloom, Joshua & Walden E. Martin, Jr., Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013.

Boykoff, Jules & Martha Gies, ¨We´re Going to Defend Ourselves: The Portland Chapter of the Black Panther Party and the Local Media Response,” Oregon Historical Quarterly, vol. 111, no. 3, 2010.

Gies, Martha, “Radical Treatment,” Reed Magazine, Winter 2009.

Koffman, Rebecca, “Ex-Black Panthers recall social activism,” Oregonian, Feb. 28, 2008.

Olsen, Jack. Last Man Standing: The Tragedy and Triumph of Geronimo Pratt. NY: Knopf Doubleday, 2000.

Website of BPP Alumni: www.itsabouttimebpp.com