Bill Berry, a leader in the Urban League for nearly thirty years, was the first director of the organization’s Portland chapter, established in 1945. At the time, Portland had experienced an influx of African Americans who had taken wartime jobs in the Kaiser shipyards. After the war ended, the loss of those jobs left hundreds with no income and few places to live, as whites sought to reestablish earlier racist policies and practices in the city. Some of the most important contributions of the Urban League under Berry’s leadership centered on housing and creating employment opportunities for Black residents.

Edwin C. Berry, known as Bill, was born in 1910 in Oberlin, Ohio, one of five children whose father, John, was a lawyer and whose mother, Kittie, was a domestic worker. John Berry died when Bill was only six years old, an event that threw the family into poverty. After finishing high school, Berry attended Oberlin College and Duquesne University. He completed his graduate degree in Sociology at the University of Pittsburg and by 1937 had begun a job with the Urban League as a group work secretary in Pittsburgh.

In 1945, Berry was hired as the first director of the Urban League chapter in Portland. He could not have moved to Portland at a more critical time, as white business leaders in the city were primarily interested in pushing Blacks out of Oregon. In 1942, the Kaiser Company had hired thousands of shipyard workers and had collaborated with the federal government to construct Vanport Village, a large multiracial housing project, for them to live in. By 1945, the Black population in nearby Portland had increased from fewer than two thousand people to over twenty thousand, and Portland was considered “one of the most discriminatory cities North of the Mason Dixon Line,” according to E. Shelton Hill, who became executive director of the Urban League in 1959.

Berry’s Urban League office took on issues that included housing restrictions based on race, union and labor discrimination, police hostility, and the legacy of anti-Black public policies. Then, in 1948, the Columbia River flooded and destroyed Vanport, which meant that Portland had to absorb five thousand displaced Black residents. Many whites in the city preferred a return to the pre-war racial status quo, but a small multiracial group of city leaders, anticipating the national post-war momentum that would blossom into the Civil Rights movement, believed that the Urban League in Portland could be a key player in addressing postwar racial tensions.

Berry set to work on racial policy changes that would have a significant effect on Portland. The League first tackled employment, which resulted in the state legislature passing the Fair Employment Practices Act of 1949, designed to set legal penalties for racial discrimination in the workplace. Oregon adopted the kind of Civil Rights legislation that would be a hallmark of the later Civil Rights movements of the 1950s and 1960s.

In 1950, Portland was one of the first cities in the nation to adopt a public accommodations law that outlawed Jim Crow practices that were common throughout the country. In the next general election, however, Portlanders voted to rescind that law. In 1953, the legislature—with the urging of the Urban League, the NAACP, and other advocates—made Jim Crow laws illegal in Oregon, a year before the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on Brown v. Board of Education. The Fair Housing Law, which made discrimination in the sale, purchase, and rental of homes illegal, was adopted by the Oregon legislature in 1957. Berry and his team at the Portland Urban League were making significant progress as the rest of the country was just embarking on the early stages of the Civil Rights movement.

In 1956, Berry accepted a position as executive director of the Chicago Urban League. Martin Luther King Jr. subsequently identified Chicago as the focal point of his northern campaign against racist practices, and he aligned with Berry, the Urban League, and other Chicago Civil Rights organizations and advocates to highlight the problems in that city. In 1961, the Chicago Urban League won a fourteen-year battle for the passage of the Fair Employment Practices law in Illinois and worked to desegregate Chicago public schools.

Bill Berry died in Chicago on March 14, 1987. He and his wife Betsy had married in 1956 and had raised five children. Betsy Berry—an activist at the Chicago Urban League, an ESL teacher, and a volunteer who served the homeless—died in 2019 at the age of ninety-nine.

-

![]()

Urban League President, Bill Berry shakes hands with Rose Festival princess, Ruth Fong.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library CN 008049

-

![]()

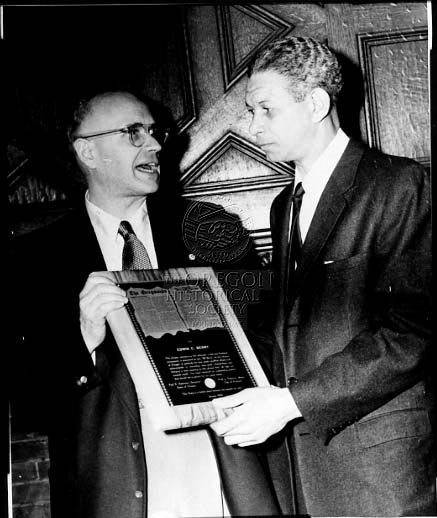

U.S. Senator, Richard Neuberger presents plaque to Bill Berry in appreciation of his service with the Urban League, 1956.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library CN 000772

-

![]()

Bill Berry counsels a student, 1950.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries -

![]()

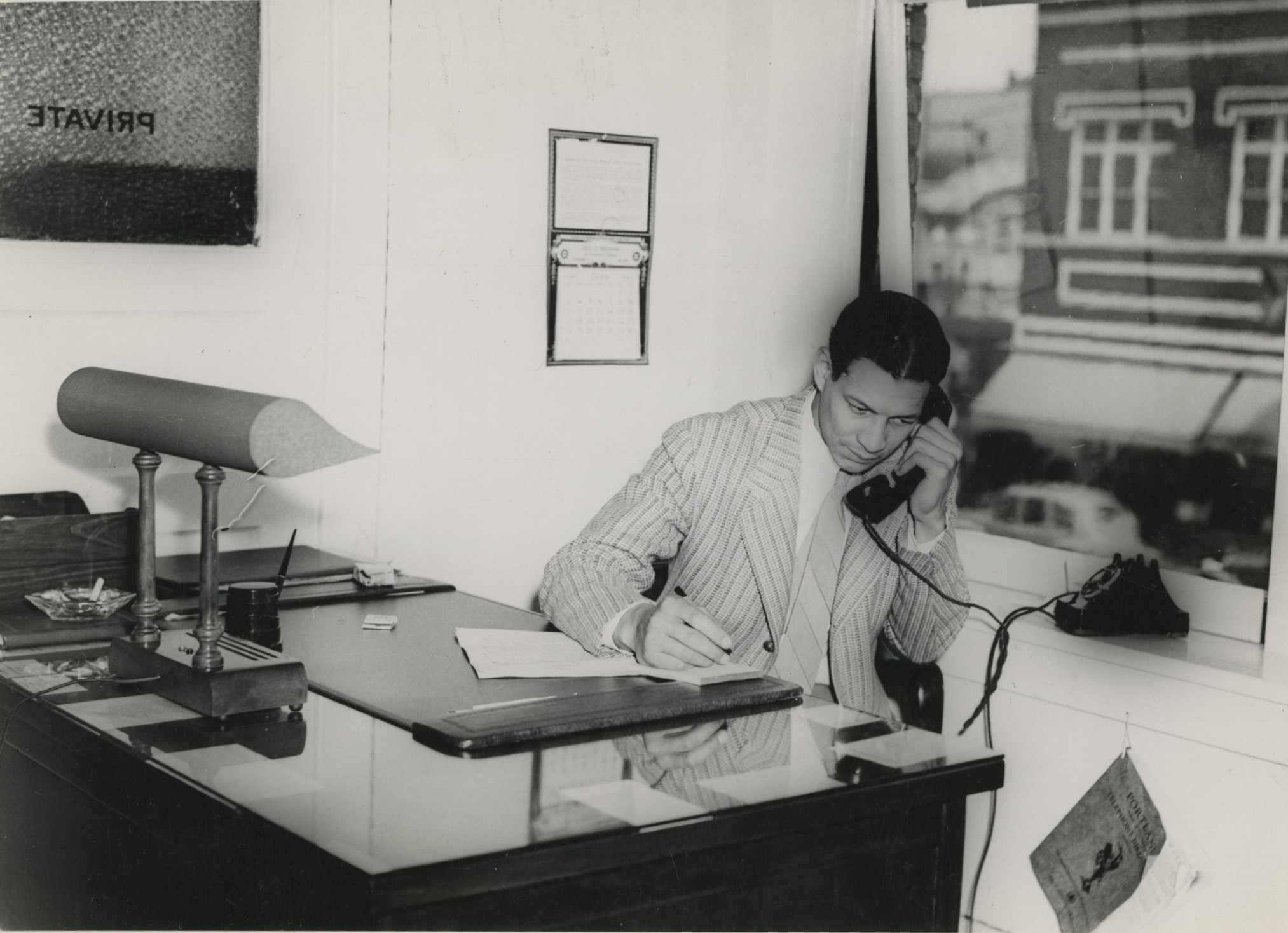

Edwin "Bill" Berry in his Urban League office.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Orhi26047

-

![]()

Bill Berry, Gov. McKay, and Tom McCall, 1949.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries -

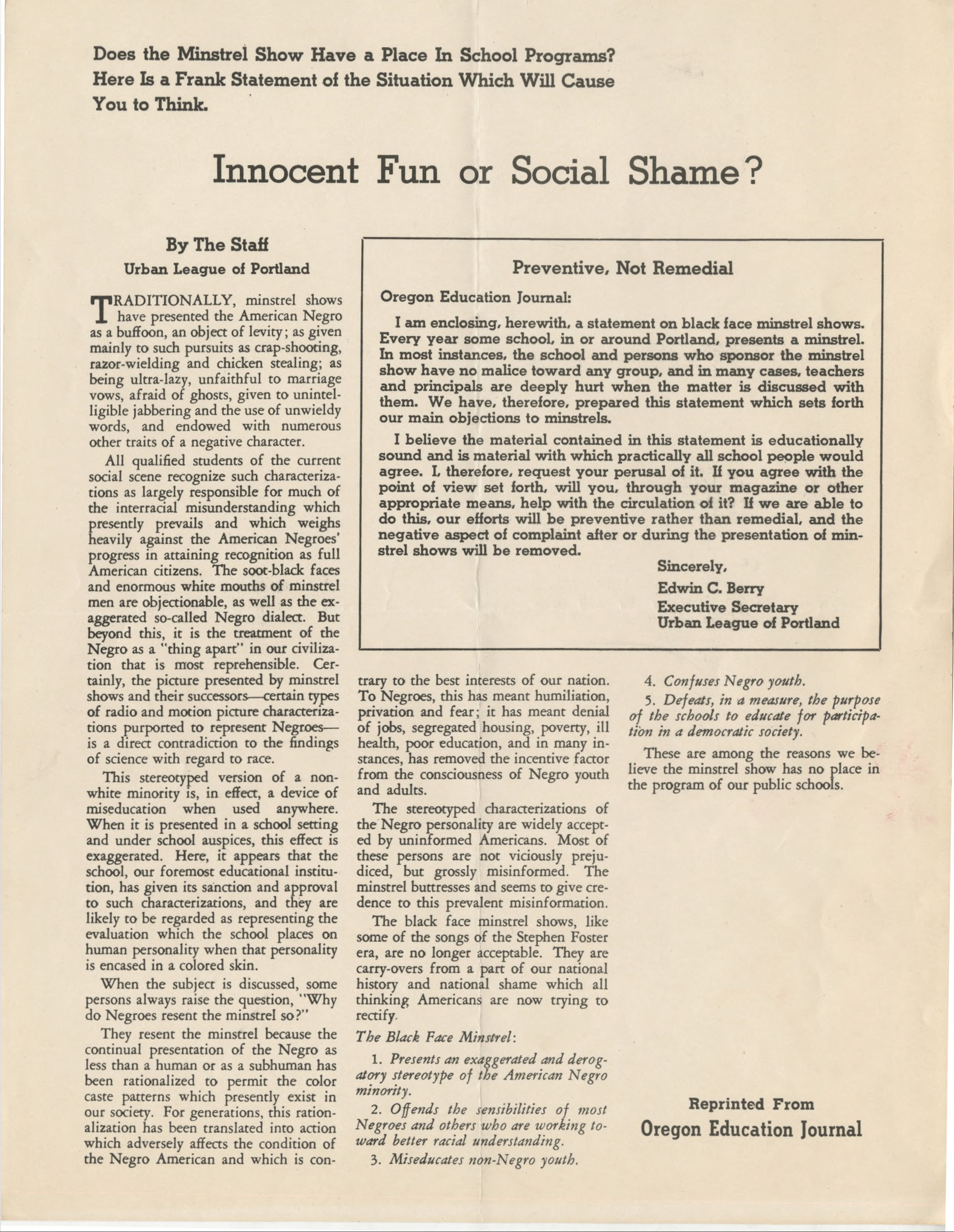

![In this concise document, the Urban League outlines for educators the history of racism in minstrel shows. Many Portland schools staged black face shows, and Exec. Sec. Bill Berry included a personal note to urge an end to such productions.]()

"Innocent Fun or Social Shame?" Urban League of Portland, c. 1950.

In this concise document, the Urban League outlines for educators the history of racism in minstrel shows. Many Portland schools staged black face shows, and Exec. Sec. Bill Berry included a personal note to urge an end to such productions. Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Mss1585_b9f5 -

![]()

8 Years of Interracial Progress: 1953 Annual Report of the Urban League of Portland.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library Mss 1585

-

![]()

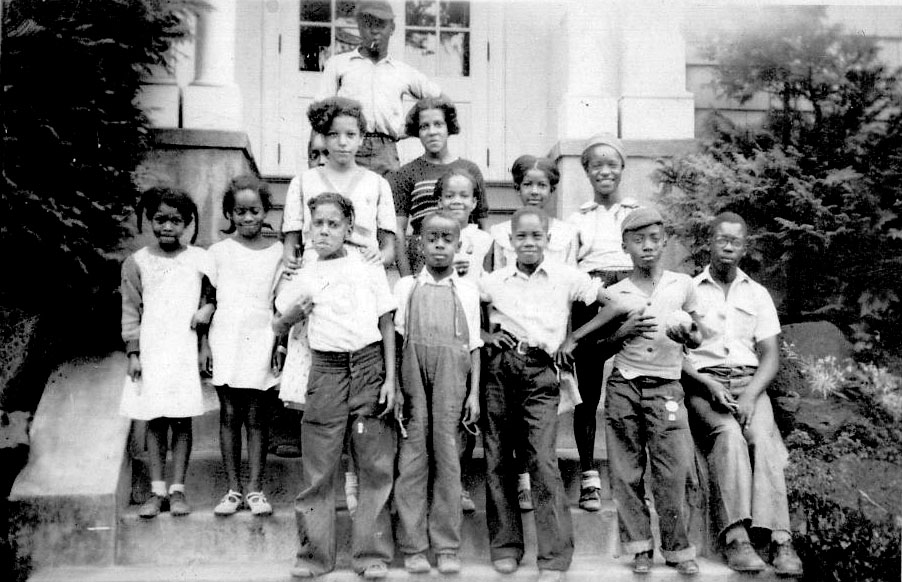

Bill Berry (left) runs an Urban League workshop.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries

Related Entries

-

![Black People in Oregon]()

Black People in Oregon

Periodically, newspaper or magazine articles appear proclaiming amazeme…

-

![Kaiser Shipyards]()

Kaiser Shipyards

During World War II, industrialist Henry J. Kaiser established three sh…

-

![Vanport]()

Vanport

In its short history, from 1942 to 1948, Vanport was the nation’s large…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Bennett, Lerone, Jr. “North’s Hottest Fight for Integration.” Ebony Magazine 31:8 (March 1962): 31-38.

Crimmins, Jerry. “Bill Berry, Ex-Urban League Director, Civil Rights Activist.” Chicago Tribune, May 14, 1987.

Millner, Darrell. On the Road to Equality: A Fifty Year Retrospective. Portland, Ore.: The Urban League of Portland, 1995.

Roose, H. “Edwin C. “Bill” Berry (1910-1987).” Black Past.

“Edwin Berry To Receive 'Man Of The Year' Award.” Chicago Daily Defender, May 27, 1968.

Pearson, Rudy. " ‘A Menace to the Neighborhood’: Housing and African Americans in Portland, 1941-1945.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 102.2 (Summer 2001): 158-179.