The fur trade was the earliest and longest-enduring economic enterprise that colonizers, imperialists, and nationalists pursued in North America. It significantly shaped North American history, especially from 1790 until 1840, when the trade played a dramatic and critical role in the Oregon Country, which included present-day Oregon and Washington and portions of Idaho, Montana, and British Columbia. Beginning with the maritime exploration and commercial expeditions of James Cook, George Vancouver, and Robert Gray, from 1776 to 1792, and ending with the United States' geopolitical domination of Oregon by 1850, the Oregon Country was transformed from what had been known as Indian Country to a territory of the United States. It was fur traders who explored the region, developed relations with the resident Native nations, and inadvertently opened the floodgates of emigration on the Oregon Trail that enabled the United States to gain control of the Pacific Northwest south of the 49th parallel.

The North American Fur Trade

Beginning well before 1600, the North American fur trade was the earliest global economic enterprise. Europeans and, later, Canadians and Americans, hunted and trapped furs; but success mandated that traders cultivate and maintain dense trade and alliance networks with Native nations. Native people provided furs and hides as well as food, equipment, interpreters, guides, and protection in exchange for European, Asian, and American manufactures.

Indicative of its deep time span and remarkable continuity, the North American fur trade and the Indian trade were essentially indivisible from roughly 1540 until 1865. A primary object of the terrestrial fur trade was beaver, the soft underfur of which was turned into expensive and sought-after beaver hats. During the 1540s on the St. Lawrence River, Jacques Cartier traded European goods, such as axes, cloth, and glass beads, to Indians who waved beaver furs on sticks from the shoreline, a sign that they had already engaged in trade with Europeans. In time, the same protocols and rituals, and the same sorts of goods, enabled the commercial and social interactions of New France’s Governor le Compte de Frontenac with Huron allies in 1690, Sir William Johnson with Mohawk clients of the British Empire in the 1750s, and the Hudson’s Bay Company’s John McLoughlin with Pacific Northwest Natives in the 1830s.

An unbroken chain spanning three centuries, the trade left multiple legacies, including the foundations for national Indian policy throughout North America. Although the trade was primarily a profit-driven enterprise, the interests of North American fur traders and their governments intersected at critical points from the 1820s through the 1840s. In quest of “soft gold” (beaver, otter, and other lightweight and highly valuable fine furs), which created fortunes large and small for lucky entrepreneurs, the fur hunters’ rosters included capable explorers who expanded the fur trade’s theater of operations and also shed light on western geography. Traders drafted many useful maps and wrote reports meant to help their governments secure geopolitical objectives. Similarly, by providing quarters, protection, and aid to scientists and artists at isolated trading posts, fur traders supported the study of Native Nations and natural history.

Indians and the Fur Trade

The trade deeply affected Native peoples' lives, for better and worse. Proximity to and alliances with traders reshaped the contours of Native politics and power across North America. Diversity characterized fur traders’ society everywhere: nowhere in North America was a society more multilingual and multicultural. Fur traders married and had children with Native women, creating the Métis people. Indians' lives were permanently altered as they gradually became dependent on guns, knives, axes, blankets, kettles, and the panoply of other useful and attractive goods acquired through the fur trade. As a result, some Native craft traditions, such as elaborate beadwork, flourished, while others, such as pottery-making, were almost forgotten. Along with other newcomers and colonizers, fur traders also became vectors for deadly diseases, such as smallpox, that greatly reduced Native populations, though no evidence suggests that traders deliberately infected Indians with diseases.

Indians became unwitting participants in a global economy as they shifted from subsistence to market hunting and operated within a debit-credit system devised by fur trade accountants. As the number of game animals diminished, Native people became more reliant on outside food sources. By about 1870, through treaties and the establishment of the reservation system, Native subsistence bases had practically collapsed, and Indians could no longer survive on the natural products of their own land. Still, the fur trade and Indian trade offer a deep-time continuity that is unmatched in North American history. One of the final historical episodes in which the fur trade played a leading role took place in the Oregon Country from 1790 to 1848.

The Early Pacific Northwest Maritime Fur Trade

British interest in the Oregon fur trade originated with the late eighteenth-century maritime expeditions of British naval officers James Cook and George Vancouver. Great Britain set out to create a vast global empire, using the tools of conquest, colonization, and commerce. The royal navy's expeditions of "discovery" and trade advanced British interests everywhere, including the practically uncharted regions of the North Pacific Ocean. Captain James Cook's Third Voyage to the Pacific in the 1770s took him to the Pacific Northwest Coast, where he encountered Native Nations such as the Haida, Tlingit, and Nootkans. After Cook was killed in Hawai'i, his associate George Vancouver continued to explore and chart the Northwest Coast. Commercial traders soon followed, exchanging copper, weapons, liquor, and varied goods for sea otter pelts. Natives also acquired syphilis, gonorrhea, and other diseases from the seafarers who sojourned on the Oregon Coast.

The United States’ geopolitical interest in the region dates to May 1792, when Captain Robert Gray’s Boston vessel, Columbia Rediviva, breasted the deadly sandbars at the mouth of a river he named Columbia. Gray’s arrival at the harbor near present-day Astoria established the first American claim to the Oregon Country. Like his predecessors, Gray traded with Nootkans and other coastal nations for sea otters to be sold in China, where the pelts fetched enormous prices and were mainly used to trim garments for the elite. Such activities initiated what became known as the China Trade, which was at first a subsidiary component of the fur trade. Over time, however, the trade developed into a much more elaborate commerce and became a tool to force China to open its markets to an expanded trade with Europe and the United States. The sea-based trade, however, was necessarily limited in scope, and eventually land-based traders would greatly expand the Oregon fur trade.

Spain, Russia, Britain, and the United States made assertions of sovereignty over Oregon and its coastal fur trade. By 1790, a rapidly declining imperial Spain had no alternative but to abandon its northernmost coastal outposts from northern California to Washington and turn its attention to securing Mexico, the heartland of its North American holdings. Maritime traffic on the Oregon Coast, however, continued to grow. Inspired by Dane Vitus Bering's expeditions (1725-1741) under the Russian flag, the Russian-American Company was founded in 1799. From sealing stations established around New Archangel in Alaska, it expanded southward. By 1822, the company operated two posts in Mexican California at Bodega Bay and Fort Ross (or Russ) on the Russian River, but simultaneous United States and British treaties with the Russians in 1824 directed the Russian-American Company sea otter hunters to remain north of 54°40'.

Over Land to the Pacific

The London-based Hudson’s Bay Company and the Montreal-based North West Company were the most important British and Canadian fur-trading outfits in nineteenth-century North America. They developed nearly identical structural and social hierarchical systems, reflecting the fur trade’s special character in North American history. Chartered in 1670 by King Charles II to his cousin, Prince Rupert, the Hudson’s Bay Company had a land grant that included most of Canada west of Ontario. Heavily capitalized, politically well-connected, and with monopoly trade rights throughout the land whose waters drained into Hudson Bay, the “Great Company” essentially owned most of present-day Canada. The company ignored the Far West until about 1800, but would eventually enter the contest for the Oregon Country.

Originating in the late 1770s, the North West Company—whose operatives were called Nor'Westers—became the HBC’s chief competitor by developing an elaborate network of river routes, trading posts, and portages south of Rupert's Land to transport furs and trade items between Montréal and the Pacific Northwest. Both companies also competed against American fur traders. Following the American War for Independence, United States and British fur traders continued to serve national interests, especially with reference to Native-white relations and assertions of geopolitical claims. Between 1783 and 1865, however, the United States lacked the capability to project meaningful military power—or enforce federal laws—in the Far West.

Emulating their northern rivals, American fur traders developed large-scale organizations and maintained the systems of interethnic and social relations and functional communitarian law that was common throughout fur country. John J. Astor’s innovative New York-based American Fur Company and Pierre Chouteau Jr.’s fur trade operations at St. Louis, Missouri, exemplified a new style of business organization that advanced the early republic’s economic frontiers, while retaining familiar patterns established by traders who had served the colonial regimes of British North America and New France.

In 1819, Spain, under diplomatic pressure from the United States, signed the Adams-Onís Treaty (also called the Trans-Continental Treaty), clarifying the southern and western boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase and further eroding Spanish jurisdiction north of Yerba Buena (present-day San Francisco). Mexico won independence from Spain just two years later, but Mexican officials thereafter devoted most of their attention to securing Alta California and the rest of northern Mexico from internal disorder as well as from potential United States intervention. The Pacific Northwest became a fruit ripe for the plucking.

The Contest for Oregon Heats Up

British claims under the so-called right of discovery would be strengthened by Alexander McKenzie and other Nor’Westers, whose trading posts lay like a string of beads from Kaministiquia (Fort William on Lake Superior in Ontario) to Fort George (formerly Fort Astoria). In 1793, McKenzie, a Canadian Nor’Wester, became the first non-Native known to reach the Pacific Ocean by an overland route.

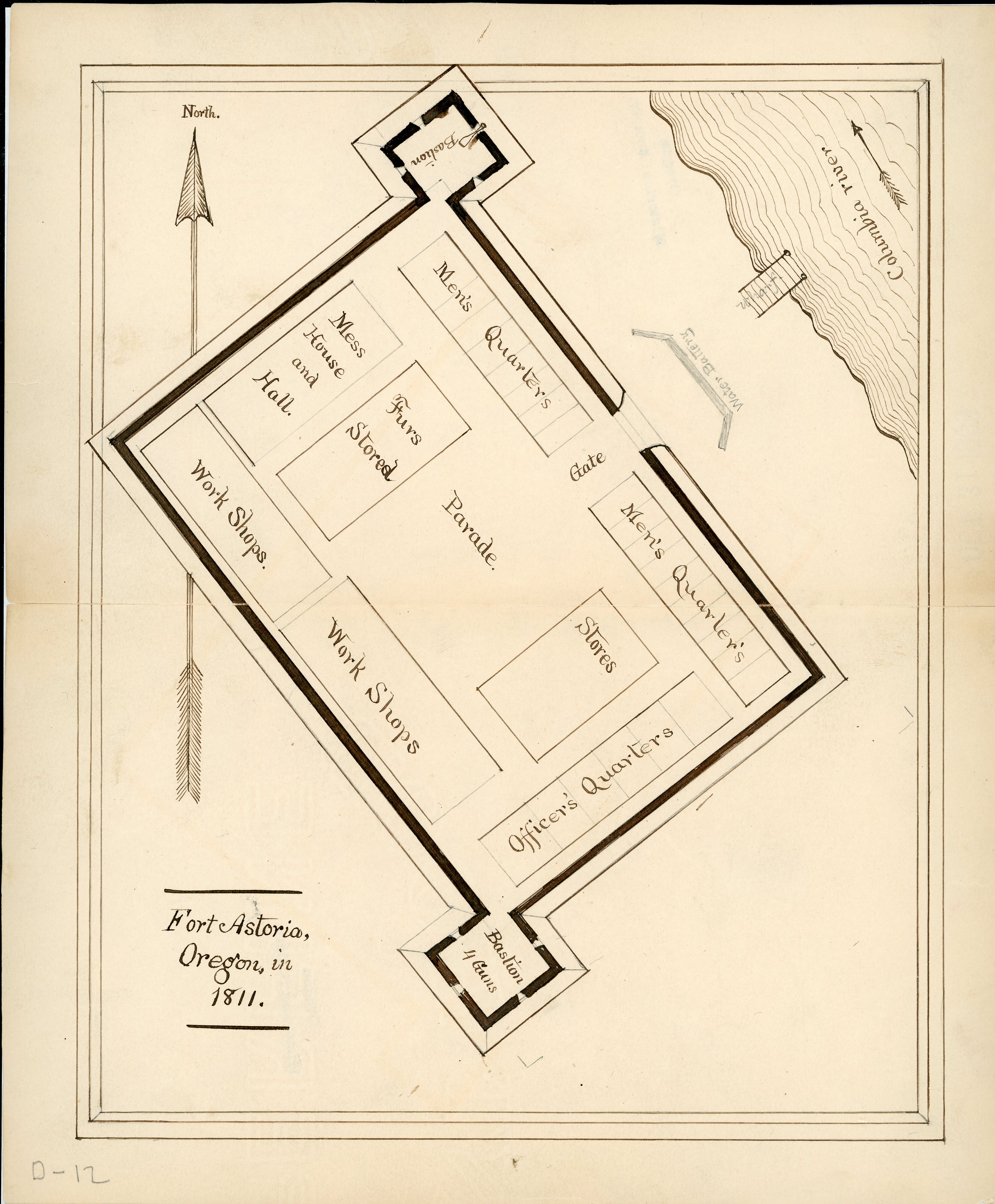

In 1808, two years after Lewis and Clark’s return to St. Louis, John J. Astor chartered his American Fur Company, and in 1810 he chartered a subsidiary unit, the Pacific Fur Company. By land and sea expeditions, Astor’s company established an American foothold at Fort Astoria in 1811. But the infant trading post became a casualty of the War of 1812. After forcing its sale, the North West Company continued to operate the trading post under a new name, Fort George. For the next dozen years, only British-Canadians traded in the interior of the Oregon County.

By 1820, Great Britain and the United States had become the chief rivals for control of the Oregon Country and its coastal and interior fur trade. In 1821, Parliament forced the amalgamation of the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company, after years of costly and disruptive conflicts that included the murder of a leading HBC official. Augmenting and refining the Nor’Westers’ trade regime, the newly expanded Hudson’s Bay Company seemed likely to seize sovereign control over the Oregon Country, as well as its fur and Indian trades, and leave the weaker United States floundering in its wake.

Unlike American fur trade outfits, the Hudson’s Bay Company directly and actively advanced Great Britain's territorial aspirations. When Lewis and Clark's Corps of Discovery returned to St. Louis in 1806, they announced that the vast fur resources of the Far West offered the most readily exploitable products. Significant numbers of American fur hunters, however, did not begin to investigate the plains and Rockies until well after the War of 1812.

In 1796, the United States Congress had created a subsidized "factory system" of federally operated Indian trading posts in an effort to regularize the Indian and fur trade, prevent abuses, and keep peace along the frontier. The factories, as they were called, were located mainly along the Mississippi River at the western frontier of settlement. More than a dozen years of continual, well-funded lobbying by John J. Astor and other influential fur traders persuaded Congress to dismantle the much-hated "monopoly" (which it never was) in 1821 and open the western trade to all comers. By 1822, numerous keelboats and pirogues began to ply the Missouri and other western rivers as the Americans based in St. Louis launched a “fur rush” into the Far West.

While the British Canadians worked westward and consolidated their grip on the Pacific Slope, a small but significant number of American fur hunters began to probe the Oregon Country. Apart from furs and Indian nations, some eagerly sought the mysterious River of the West, or Rio Buenaventura, which was supposed to provide an easy water passage from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Coast. No such passage existed, but two hundred years of searching for it produced much knowledge about western American geography.

From New Mexico, the Upper Missouri, and the Platte River came a few hundred Mountain Men, including Joseph Meek, Robert “Doc” Newell, Nathaniel Wyeth, Ewing Young, and Jedediah S. Smith, seeking profits and adventure in “the Ouragon.” American entrepreneurs active in Oregon included the firm of Smith, Jackson & Sublette (1826-1830), Captain B.L.E. Bonneville (1832-1835), Nathaniel J. Wyeth (1832-1837), and a handful of fur company employees whose expired company contracts made them “free trappers,” or independent hunters.

Jedediah S. Smith, a New Yorker, enlisted in William H. Ashley and Andrew Henry’s 1822 Rocky Mountain trapping expedition. By 1825, he had entered a partnership with William Ashley; Smith bought him out a year later, creating Smith, Jackson & Sublette. From 1824—when Smith identified the transcontinental significance of South Pass in Wyoming—until 1828, he and others explored and harvested furs in California and the Oregon Country.

For about two years Smith’s brigade alternately shadowed and dodged their HBC rivals, the Snake Country Brigades (1818-1830), dispatched from Fort Vancouver under the supervision of Alexander Ross and, later, Peter Skene Ogden. The Snake Brigades were ordered to implement the company’s policy of creating a “fur desert” in Oregon to dissuade American interlopers, and intensive trapping from 1818 to 1830 severely reduced beaver populations. Nonetheless, from the 1820s on there was increasing interest among Americans to acquire Oregon as a territory.

The contentious competitors occasionally threatened one another, and the Americans persuaded some formerly bound Hudson’s Bay Company men to desert their employers, but no bloodshed marked these interactions. Still, intensive competition in Oregon meant that HBC engagés (similar to indentured servants) sometimes bargained for higher wages or deserted because the American traders promised lower prices for trade goods. Precise numbers are furtive, but it is reasonable to assume that the combined fur harvest of the HBC men and the Americans working the Snake Country in the 1820s accounted for twelve to sixteen thousand beaver skins annually, along with many mink, otters, muskrats, martins, and other furs. With beaver fur approaching its highest nineteenth-century market value, Oregon furs sold in London for about five dollars a pound.

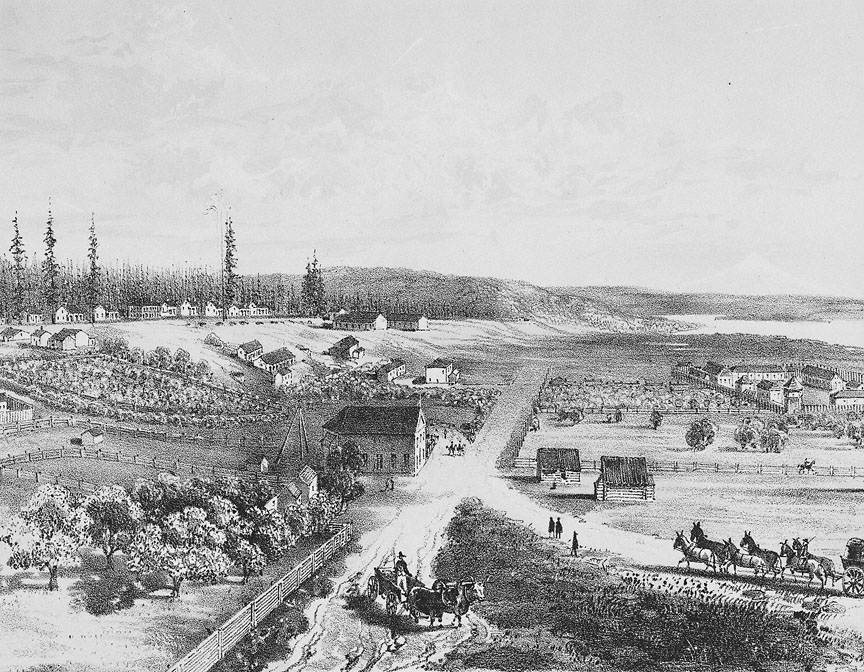

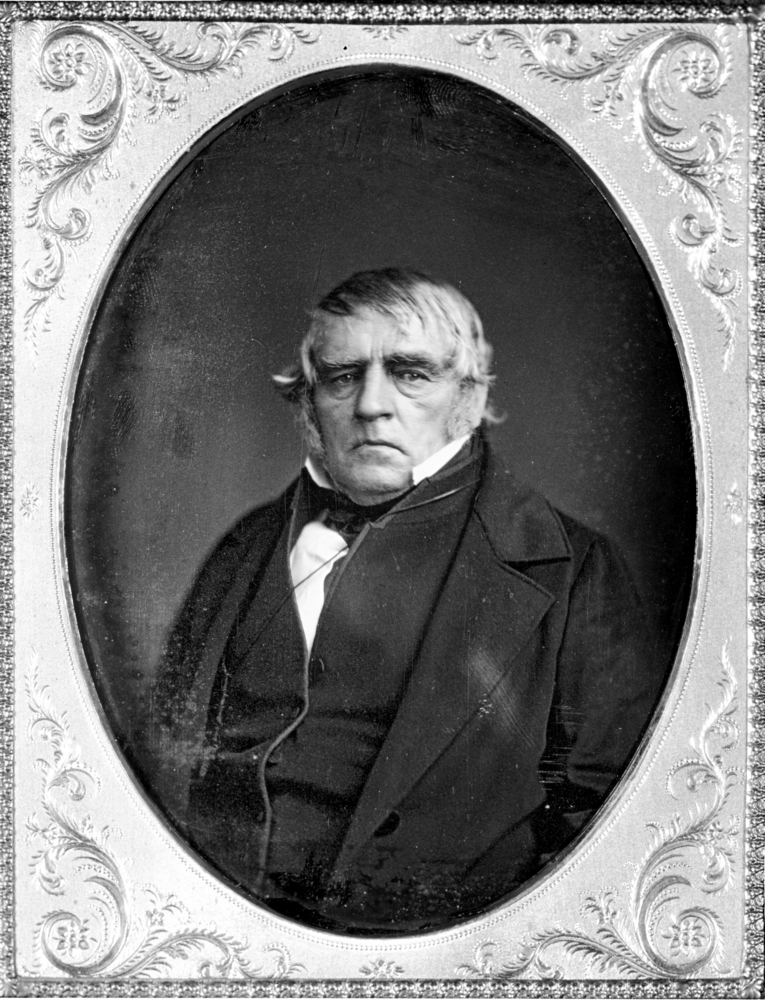

From 1825 through the 1830s, several hundred fur hunters from both the United States and Canada prowled the interior Pacific Northwest, harvesting peltry. The chief factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s headquarters for its Columbia District in Fort Vancouver (1825-1850) exercised considerable regional authority until 1850. Company policy dictated that traders must never antagonize Indians and, prior to the Americans’ arrival, the HBC generally preserved peace and enjoyed a good reputation among Native people. As American farmers flocked to Oregon after 1840, the company’s influence over the trade and Indian-white affairs began to wane.

Fur traders’ caravans also brought the first missionaries to the Oregon Country. By 1835, United States-based missionaries, including Catholics (such as Pierre Jean DeSmet and Nicholas Point) and Protestants (such as Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and Jason Lee), were building mission stations in present-day Oregon, Idaho, and Washington. After 1840, the Whitman mission at Waiilatpu served mainly as a rest and recruitment stop for American emigrants en route to Oregon. Trail traffic boomed, and by 1846 several thousand non-Natives resided in Oregon. Oddly, a probate case involving the contested estate of Ewing Young, a former beaver trapper, inspired citizens to create an ad hoc provisional government (1843-1846), which initiated a movement for statehood. The newcomers eroded the Indians’ resources, taking land and harvesting animals, and introduced much discord.

In November 1847, angry members of the Cayuse Nation killed the Whitmans and a dozen others at Waiilatpu. In a final demonstration of its power, the Hudson’s Bay Company negotiated the safe release of many survivors of the attack. But HBC dominance of the region was at an end. Spurred to action by the Whitman disaster, Congress created the Oregon Territory in 1848. Since the 1830s, retired Hudson’s Bay Company employees, other fur-men, and their mixed-ancestry families had lived in the Willamette Valley, primarily in French Prairie and Oregon City. But American farmers soon flooded into the Willamette Valley and elsewhere, permanently disrupting the old company’s trade and life for all of the region’s inhabitants. An 1855 U.S. Pacific Railroad Surveys Report lithograph depicts a quite tame-looking Fort Vancouver, surrounded by farms, fields, buildings, and orchards. All of these things emblemized Oregon’s dramatic transformation since 1825. In the emigrants’ view, Oregon had become “civilized.”

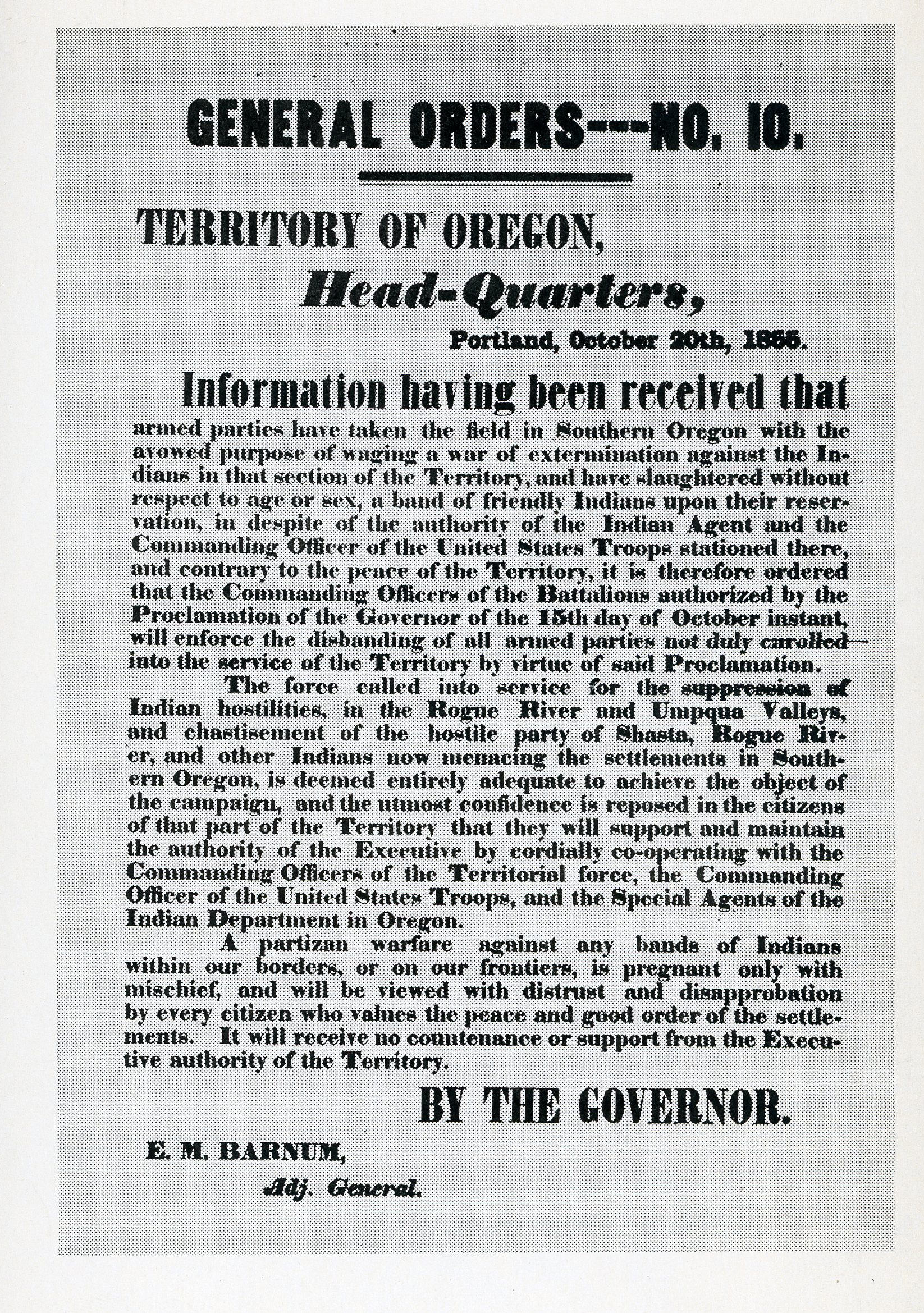

Territorial status brought down the curtain on the old-time fur trade in Oregon, and Indian-white relations rapidly degraded from bad to worse. Intermittent violence had occurred since the 1780s, but as whites—especially gold miners—expropriated Indian land throughout southern Oregon, violent confrontations escalated, resulting in the Rogue River Wars of 1855-1857. Oregon militiamen rounded up and killed several hundred Indians, then seized their lands through forced treaties.

The End of the Fur Trade Era

By the time Oregon achieved statehood in 1859, military sutlers and civilian entrepreneurs had supplanted the fur men and their trading posts, and the U.S. government had asserted an exclusive legal right to control Natives’ lives through the Office of Indian Affairs (later renamed the Bureau of Indian Affairs). The brief era of the Mountain Men was long over, and Indians faced impoverished and terribly uncertain futures. Fur hunting and fur sales continued in limited form for several more decades and is now highly regulated.

By the dawn of the twentieth century, western game animal populations had plummeted. As in other states, the beaver population in Oregon reached its nadir by roughly 1900. The Oregon legislature temporarily prohibited beaver trapping from 1899 until 1919, enacted its first conservation measures in 1920, and established a relocation program in 1932. Another moratorium was placed on public beaver-trapping from 1937 until 1951. Since then, the beaver population, like that of other fur-bearers, has increased substantially, and Oregon's Department of Fish and Wildlife now manages the control, relocation, and harvesting of fur-bearers.

From 1992 until 2012, the annual harvests of licensed (and reporting) Oregon hunters and trappers ranged from 2,500 to 5,500 beaver pelts, 2,500 to 20,000 muskrat pelts, and 266 to 578 river otter pelts, along with substantial numbers of red fox, grey fox, martin, mink, badger, and raccoon pelts. Average fur prices have fluctuated considerably since the 1950s, with a general decline in beaver pelt prices. Fetching $12 each in 1955 (approximately $107 in 2016 dollars), they stood at $20 in 2014. Some furs, such as river otters, have remained about evenly valued over time, but bobcat furs began to skyrocket in the 1970s. Worth only $3 each in 1955 (approximately $27 in 2016), they surpassed $100 in 1975 (approximately $430 in 2016) and rose to an all-time high of $493 in 2012.

Conservationists, Native nations, land management bureaus, corporations, hunters, farmers, and politicians collectively shape the state and federal policies that determine the fur-bearers’ future. Among all the states, only New York and Oregon feature flags that prominently display a beaver, an iconic reminder of the continent-wide historical significance of the fur trade.

-

![]()

Sea otter, illustration from West Shore magazine.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi39207

-

![]()

Beaver trap.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Museum, 218

-

![]()

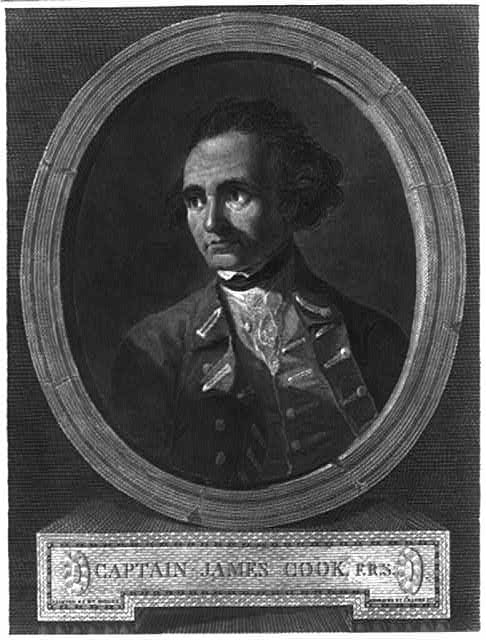

Capt. James Cook, 1777.

Courtesy Library of Congress

-

![]()

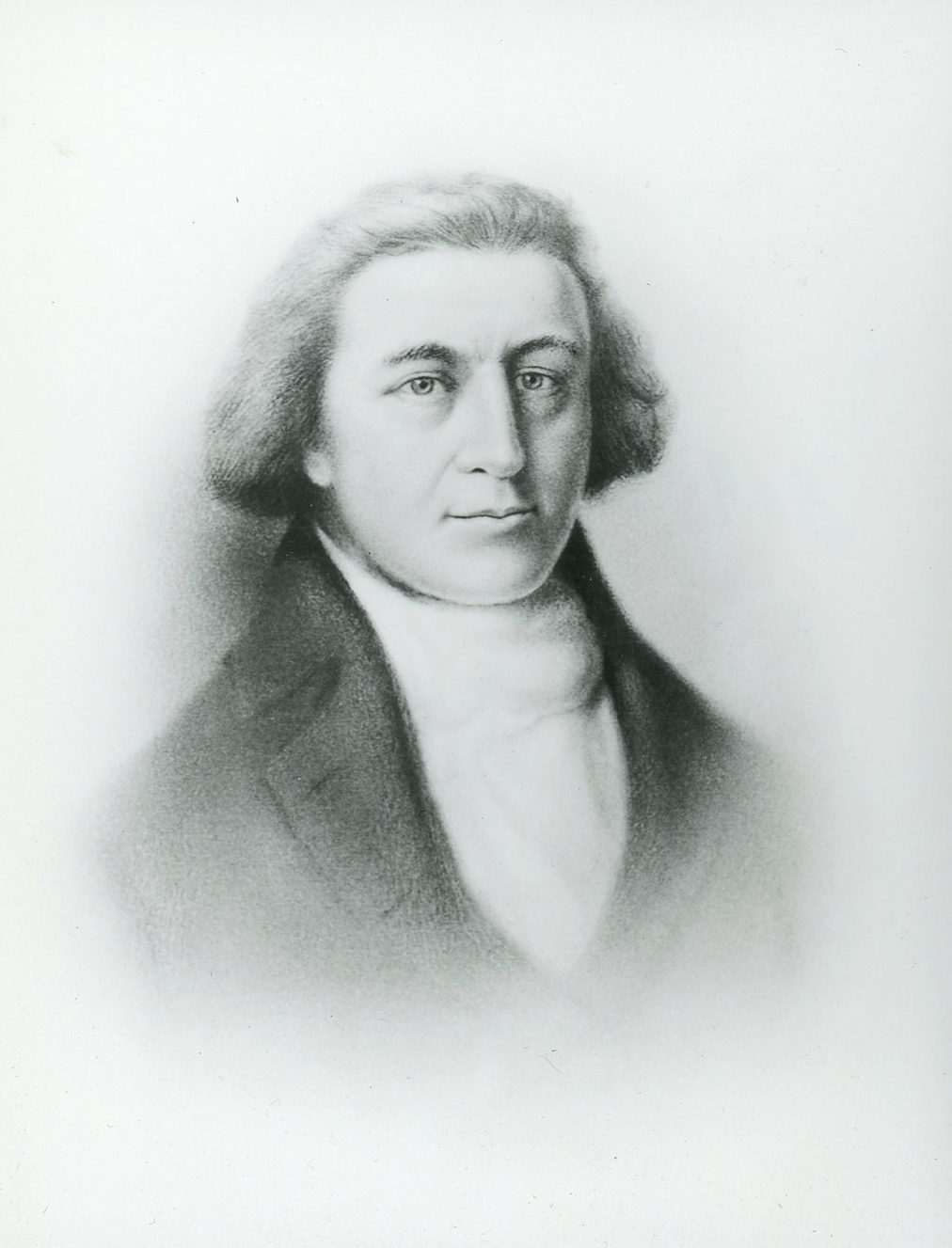

George Vancouver.

Courtesy National Portrait Gallery

-

![]()

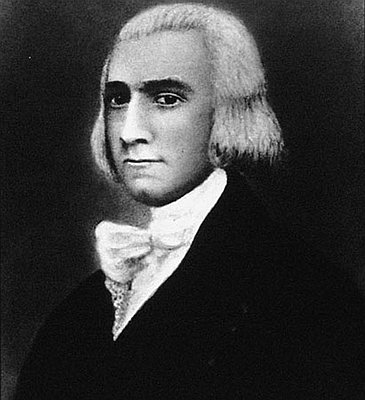

Robert Gray, trader and captain of the Columbia Rediviva.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, 004537

-

![]()

John Jacob Astor, 1877.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi53

-

![]()

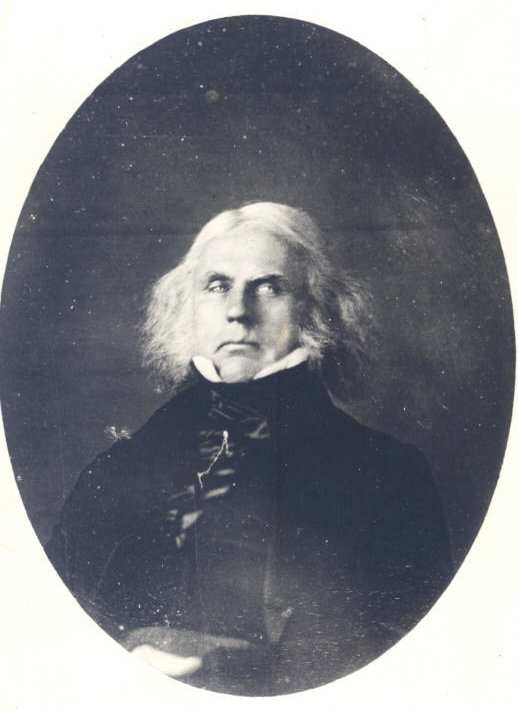

Dr. John McLoughlin.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi73380

-

![]()

Joe Meek.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 012658

-

![]()

Alexander Ross.

Archives of Manitoba, Ross, Alexander 4 (N21467)

-

![Peter Skene Ogden]()

Peter Skene Ogden.

Peter Skene Ogden Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi707

-

![]()

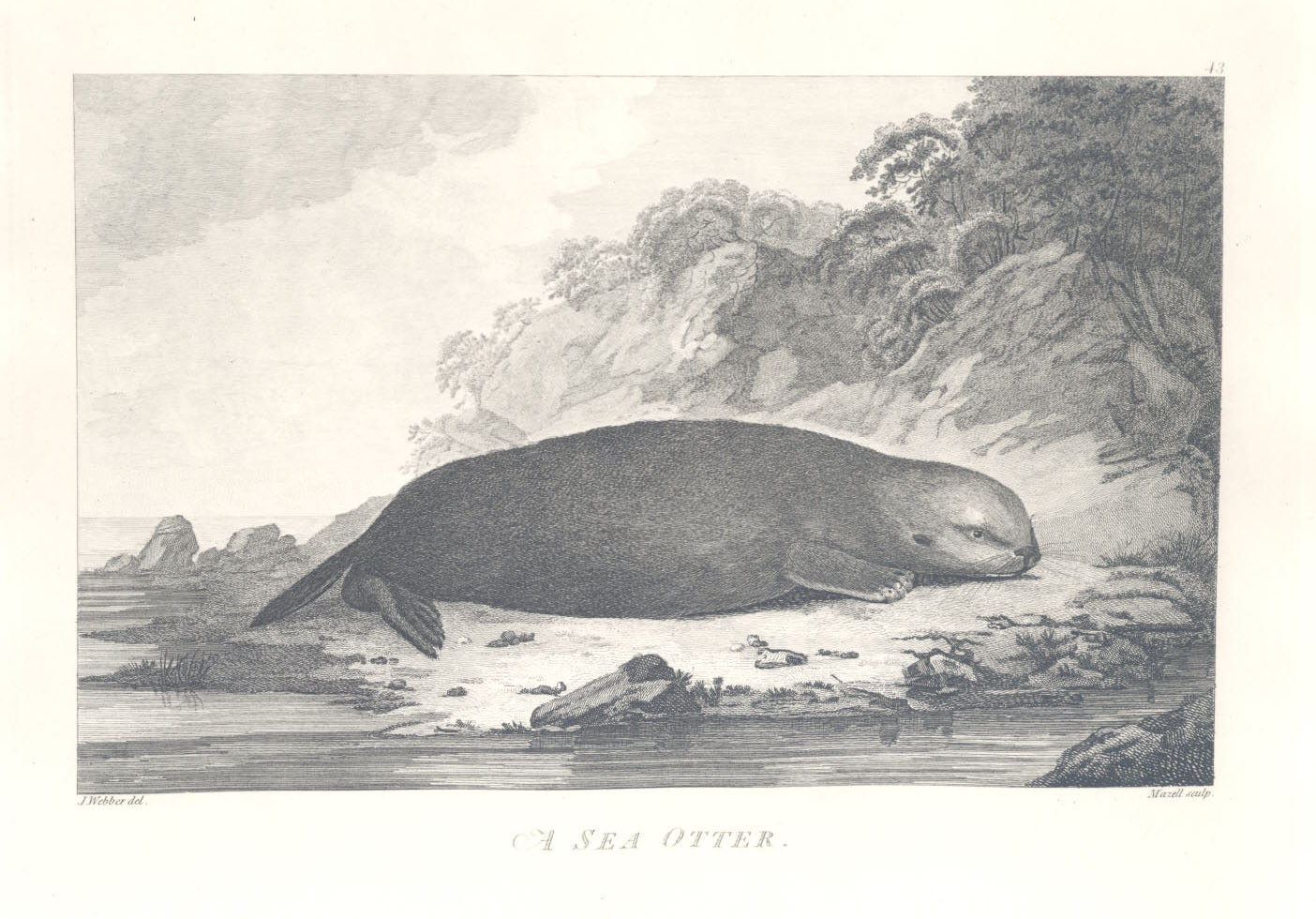

Sea otter, illustration from Cook's voyage .

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi3559

Related Entries

-

![Astor Expedition (1810-1813)]()

Astor Expedition (1810-1813)

The Astor Expedition was a grand, two-pronged mission, involving scores…

-

![Fort Vancouver]()

Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver, a British fur trading post built in 1824 to optimize th…

-

![French Prairie]()

French Prairie

Located in Oregon's mid-Willamette Valley, French Prairie was resettled…

-

![George Vancouver (1757-1798)]()

George Vancouver (1757-1798)

The role George Vancouver played in Oregon history is tangential, yet i…

-

![Hudson's Bay Company]()

Hudson's Bay Company

Although a late arrival to the Oregon Country fur trade, for nearly two…

-

![John McLoughlin (1784-1857)]()

John McLoughlin (1784-1857)

One of the most powerful and polarizing people in Oregon history, John …

-

![Lewis and Clark Expedition]()

Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Expedition No exploration of the Oregon Country has greater histor…

-

![Peter Skene Ogden (1790-1854)]()

Peter Skene Ogden (1790-1854)

More than any other figure during the years of the Pacific Northwest's …

-

![Robert Gray (1755–1806)]()

Robert Gray (1755–1806)

On May 11, 1792, Robert Gray, the first American to circumnavigate the …

-

![Rogue River War of 1855-1856]()

Rogue River War of 1855-1856

The final Rogue River War began early on the morning of October 8, 1855…

-

![Sea Otter]()

Sea Otter

America’s introduction to the lucrative Pacific Northwest Coast fur tra…

-

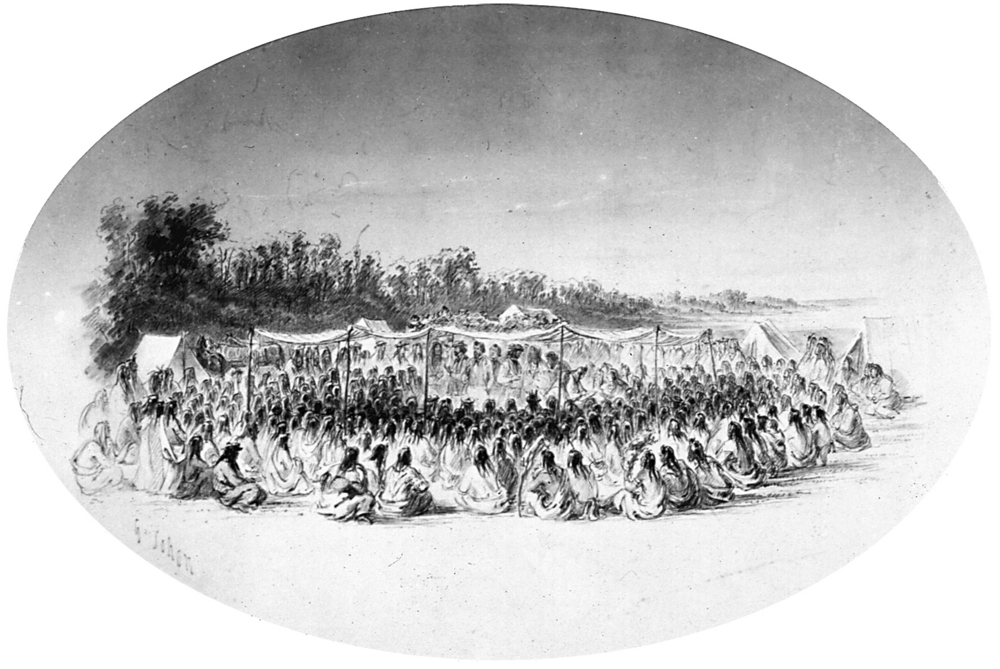

![Walla Walla Treaty Council 1855]()

Walla Walla Treaty Council 1855

The treaty council held at Waiilatpu (Place of the Rye Grass) in the Wa…

-

![Willamette Valley Treaties]()

Willamette Valley Treaties

From 1848 to 1855, the United States made several treaties with the tri…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Howay, Frederick W., ed. Voyages of the Columbia to the Northwest Coast, 1787-1790 & 1790-1793, reprint. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 1990.

Reid, John Phillip. Contested Empire: Peter Skene Ogden and The Snake River Expeditions. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002.

Barbour, Barton H., Jedediah Smith: No Ordinary Mountain Man. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2009.