America’s introduction to the lucrative Pacific Northwest Coast fur trade occurred on August 10, 1788, when the sloop Lady Washington, under Captain Robert Gray, traded with local people for sea otter skins just north of Yaquina Bay. Four days later, Gray and his eleven-man crew entered Tillamook Bay flying the American flag, the first recorded American landing on the coast. The Columbia Rediviva under Captain John Kendrick carried the furs to Macao and Canton as part of the China trade.

Sea otters (Enhydra lutris), the largest of the otter species, are adapted to forage, play, sleep, and give birth in a marine setting without being on land. Where other marine mammals have insulating layers of blubber, the sea otter’s insulation and buoyancy depend on water-resistant, ultra fine, lustrous, dark underfur with long white-tipped guard hairs that give it a frosted appearance. The animals rub and pat their fur meticulously to cleanse it, blowing into and aerating it with a churning paw motion. Trapped air bubbles help provide vital insulation. They originally ranged around the North Pacific coast, from the Kuril Islands north of Japan to the west coast of Baja.

With a lifespan of from fifteen to twenty years, sea otters forage inshore waters that are dominated by the giant kelp that clings tenaciously to the sea floor. Kelp strands reach as far as 200 feet upward to the sea surface to provide a forest-like cover for sea otters and their prey. Sea otters daily consume a quarter of their body weight. Their diet includes crabs, clams, abalone, mussels, sea urchins, octopuses, and bottom fish such as lingcod. The single sea otter cub can be born at any time of the year, and almost all births take place at sea. The mother embraces and grooms her cub attentively for the year it is dependent on her.

The smallest of marine mammals—males average sixty-eight pounds and females forty-eight pounds—sea otters at one time had the world’s most valuable pelt. Eighteenth-century Russian traders, who called otter pelts “soft gold,” worked from outposts in Alaska. They pressed Aleut men who owned lath-frame and sealskin-covered kayaks into service beginning in the 1760s, creating a highly lucrative and exclusive trade with China. In time, Russian ships with Aleut hunters ranged the length of the West Coast. British, French, Portuguese, and American ships joined the trade when Captain James Cook's third expedition made it known that there was money to be made in trade with Natives for sea otter pelts, their sale to China, and a return home with silk, tea, fine chinaware, porcelain, and exotic woods.

Sea otter furs, worn as robes or blankets, served as a medium of exchange and status for Native people. At the time when Captain Gray sailed over the Columbia River bar to trade with the Chinook people, for example, one pelt was worth five iron chisels, and four pelts were traded for one sheet of copper or for a quantity of beads, preferably blue.

By 1790, an estimated 250,000 sea otter pelts worth $50 million had been taken from coastal waters; and by 1867, when Russia sold Alaska to the United States, otters were near extinction. By 1911, both sea otters and northern fur seals were given protection under an international treaty signed by Great Britain (for Canada), Russia, Japan, and the United States. The Aleutian Islands were declared a National Wildlife refuge in 1913, and the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 reinforced their protection in U.S. waters.

Because of such efforts, rafts of remnant sea otters began a slow recovery on the Aleutian Islands, the Alaska Peninsula, and California’s Big Sur coast. Southeast Alaska, British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon coastlines remained devoid of sea otters until a collective effort at reintroduction was undertaken in 1967 on Amchitka Island in the central Aleutians, where the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was holding deep drilling tests. The AEC built four holding pens with circulating seawater and cold storage for squid and rockfish to feed the sea otters. Wildlife biologists from Alaska, Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia brought commercial fishing gill nets to tangle-trap sea otters in the dense kelp beds, and an AEC-chartered C-130 Hercules cargo plane brought the sea otters to release areas.

A century after being hunted to extinction on the Oregon Coast, the first release of twenty-nine sea otters arrived at Cape Blanco Coast Guard airstrip on July 18, 1970. They were transferred to a temporary floating sea cage at Port Orford for observation and towed to Orford Reef kelp beds for release the next day. An additional sixty-four sea otters were released in 1971 at Port Orford and Simpson Reef off Coos Bay. The reintroduction was not successful, and Oregon’s sea otters faded away over a nine-year period. Recent sightings of sea otters may be transient males from California or Washington’s Olympic coastline. One of the greatest current concerns for the stability and return of sea otters is the threat of oil spills at sea.

-

![]()

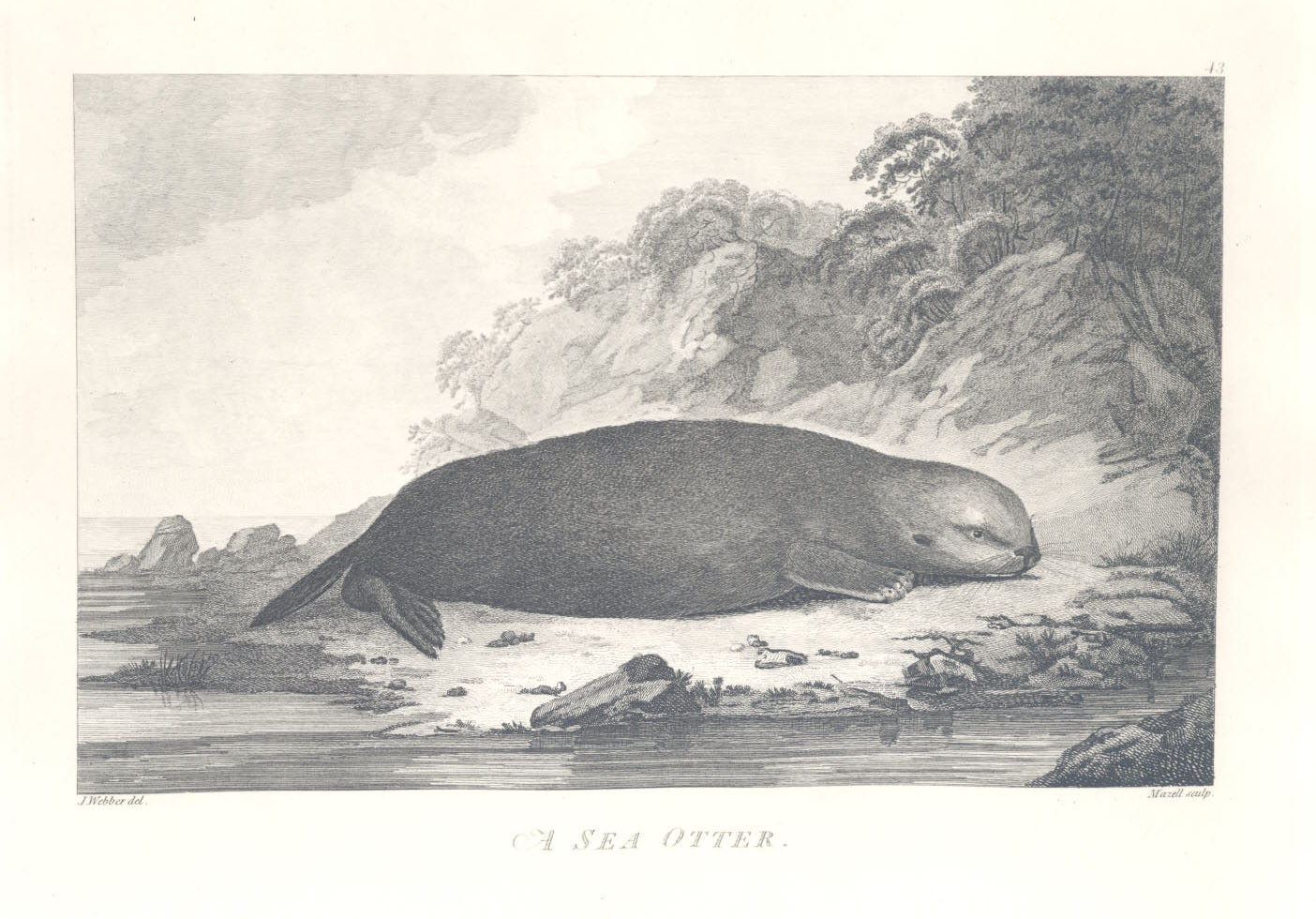

Sea otter, illustration from Cook's voyage .

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi3559

-

![]()

Sea otter, illustration from West Shore magazine.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi39207

Related Entries

-

![Fur Trade in Oregon Country]()

Fur Trade in Oregon Country

The fur trade was the earliest and longest-enduring economic enterprise…

-

![Robert Gray (1755–1806)]()

Robert Gray (1755–1806)

On May 11, 1792, Robert Gray, the first American to circumnavigate the …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Ogden, Adele. The California Sea Otter Trade, 1784-1848. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1941.

Scammon, Charles M. The Marine Mammals of the Northwestern Coast of North America. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1968.