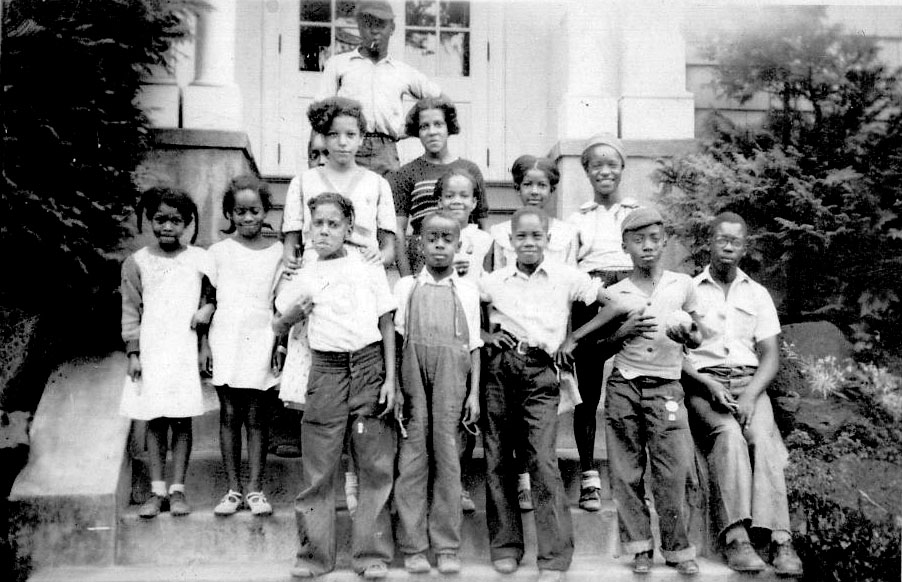

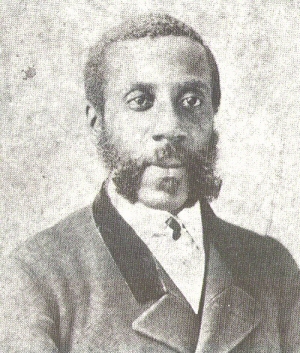

From his arrival in Oregon in about 1864 until his death in 1914, James Beatty was a highly regarded member of Portland’s African American community. A businessman and respected property owner, he was a leader in community affairs, an activist and an advocate for civil rights.

Born on October 16, 1830, in Shaker, Kentucky, James William Beatty was the third of ten children. His mother, Lydia Ann Rowe, was born in Culpepper County, Virginia, the daughter of white slaveholder James H. Rowe and one of his slaves, Frances “Fannie” Anderson. James’s father, Adam Beatty, was a farmer and “free person of color.” By the mid-1840s, the family had settled in Hanover, Indiana, where Adam died in 1849, leaving a farm and personal estate of about $2,200—over $72,000 in 2020 dollars. On January 8, 1850, nineteen-year-old James Beatty and fifteen-year-old Mary Laurinda Jane Smith of Louisville—both “free persons of color”—were married by Martin John Spalding, Bishop of Louisville and later Archbishop of Baltimore.

In Hanover, the newlyweds attended a local school and farmed next to James’s mother and siblings. In 1851, Indiana prohibited Black immigration and required resident Blacks to register, but neither James nor Mary registered. Perhaps James’s share from his father’s personal estate—about $88, or $3,000 in 2020 dollars—provided what the couple needed to leave Indiana. By the early 1860s, they were living in Victoria on Vancouver Island.

The Beattys settled in Portland in about 1864, but what drew them to Oregon is not clear. Few Blacks lived in the state—only 318 by 1870—and Oregon had a poll tax (1862) and an anti-miscegenation law (1862). It was also the only free state admitted to the Union with a constitutional Black exclusion clause. But the Beattys were undeterred and consistently challenged the injustice of legal and cultural scripts for race and gender in Oregon.

The couple was enterprising and persevering. James started a whitewashing and kalsomining business, did general jobbing, and had a market for “fish, oysters and game.” He was a janitor, house mover, and sewer contractor and eventually described himself as “a landlord.” Mary was a dressmaker and offered rooms in their residence, first on Salmon Street and later on Yamhill.

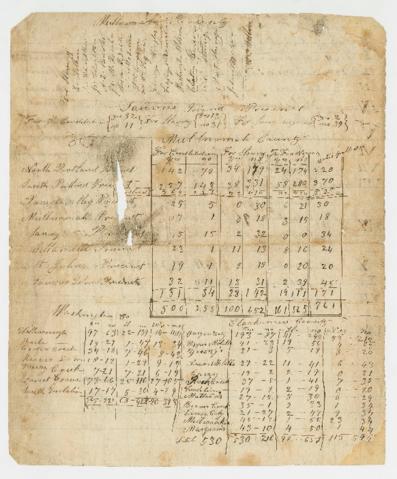

They acquired substantial real estate, both individually and jointly, and sold property to one another. In 1869, for example, James purchased a downtown Portland lot from Oregon Iron Works for $800 (over $15,000 in 2020 dollars); in 1881, after passage of Oregon's Married Women's Property Acts in 1878 and 1880, he sold the same Yamhill Street property, with improvements, to Mary, for $3,000 (about $72,000 in 2020 dollars). As early as 1874, the Beattys had acquired separate properties in Cornelius, Washington County, where they farmed for about a decade. In 1883, James identified himself in the Portland directory as a "farmer and speculator," and the Oregonian described him in 1892 as "the owner of some valuable property."

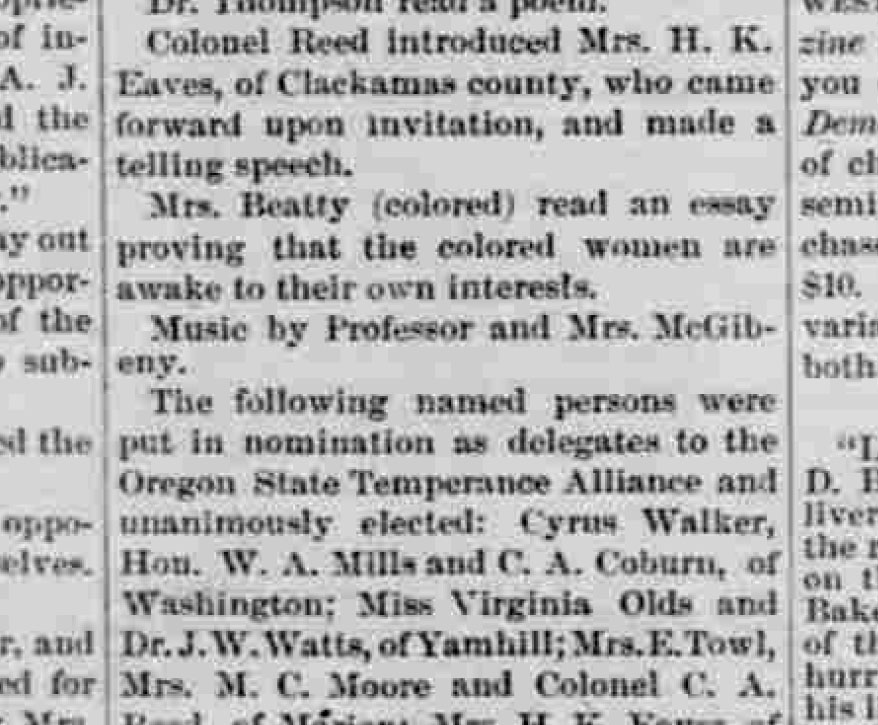

For the Beattys, community involvement and bold leadership were part of responsible citizenship. In 1871, James became a trustee of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, and he subscribed to the Railroad Fund to aid the Willamette Valley Railroad, a project launched in 1874 to connect the Willamette Valley with international shipping at Yaquina Bay. In 1872, he helped found the Republican Campaign Club, and Mary attempted to vote in the presidential election.

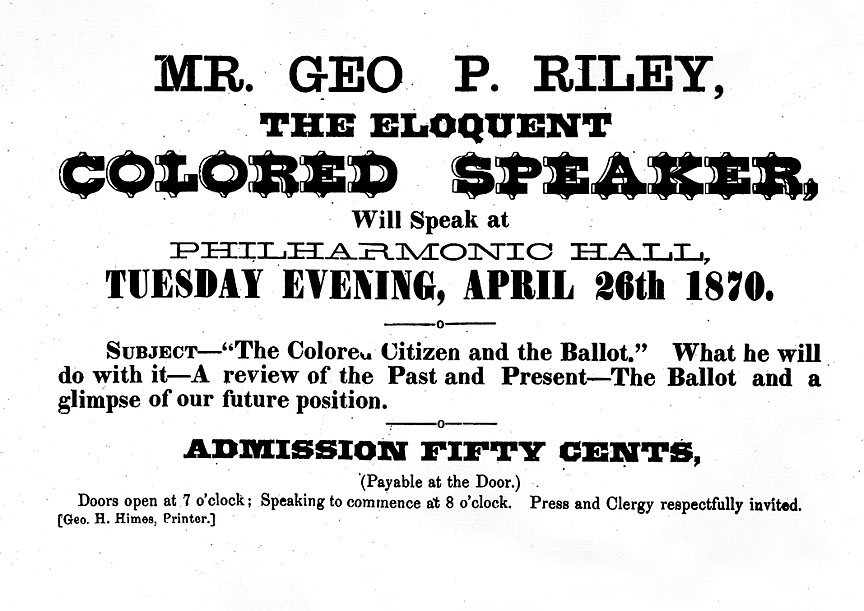

James Beatty was president of Portland’s Grand Ratification Jubilee, held on April 6, 1870, to celebrate the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment. The Jubilee began with a “torch-light procession of colored men” led by an infantry band through Portland to the Multnomah County Courthouse, where Beatty opened the proceedings “in a brief but excellent speech.” Other speakers included Black orator George Putnam Riley, former Governor Addison C. Gibbs, and Brig. Gen. Rufus Saxton. “The whole affair,” the Oregonian observed, “was very creditable to colored citizens.”

Beatty also worked to provide equal employment opportunities for Blacks. The Oregonian reported in August 1892 that James Beatty, “a well-known colored man,” was serving as “an entering wedge to open a way for colored men to get on the police force.” Two years later, the Abraham Lincoln Colored Republican Club, which James had helped found in 1888, lobbied for civil service jobs for Blacks. One of their successes was the appointment of George Hardin as Portland’s first Black police officer (1894–1915) and as deputy sheriff of Multnomah County (1915–1938).

Mary Beatty died on September 28, 1899; the couple had no children. On February 8, 1902, James married Marie Felicia Baron, a forty-four-year-old white woman born in Herbeumont, Belgium. To avoid the criminal sanctions of the 1866 law banning intermarriage, the couple obtained their marriage license in Vancouver, Washington, where they were married by a Catholic priest. They lived at James’s Yamhill address and later, as James’s health was failing, with Clement and James A. Cini, Marie’s daughter and son-in-law. James died on May 5, 1914, and was buried at Greenwood Hills Cemetery, where he and Mary share a gravesite.

James Beatty did not live to witness repeal of Oregon’s Black Exclusion Clause in 1926 or the end of the ban on intermarriage in 1951 or the legislature’s ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1959, but he had lived the history. Even when he was too ill to sign his name, he voted in 1912 by making his mark—an X—on his registration card, a powerful reminder of who he was.

-

![]()

Broadside for a lecture by George P. Riley, 1870.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, OrHi24847

-

![Former Norsk Dansk Methodist Episcopal Church]()

First AME Zion Church on N. Vancouver, 1980.

Former Norsk Dansk Methodist Episcopal Church Courtesy University of Oregon, PNA_06246 mdr06704

Related Entries

-

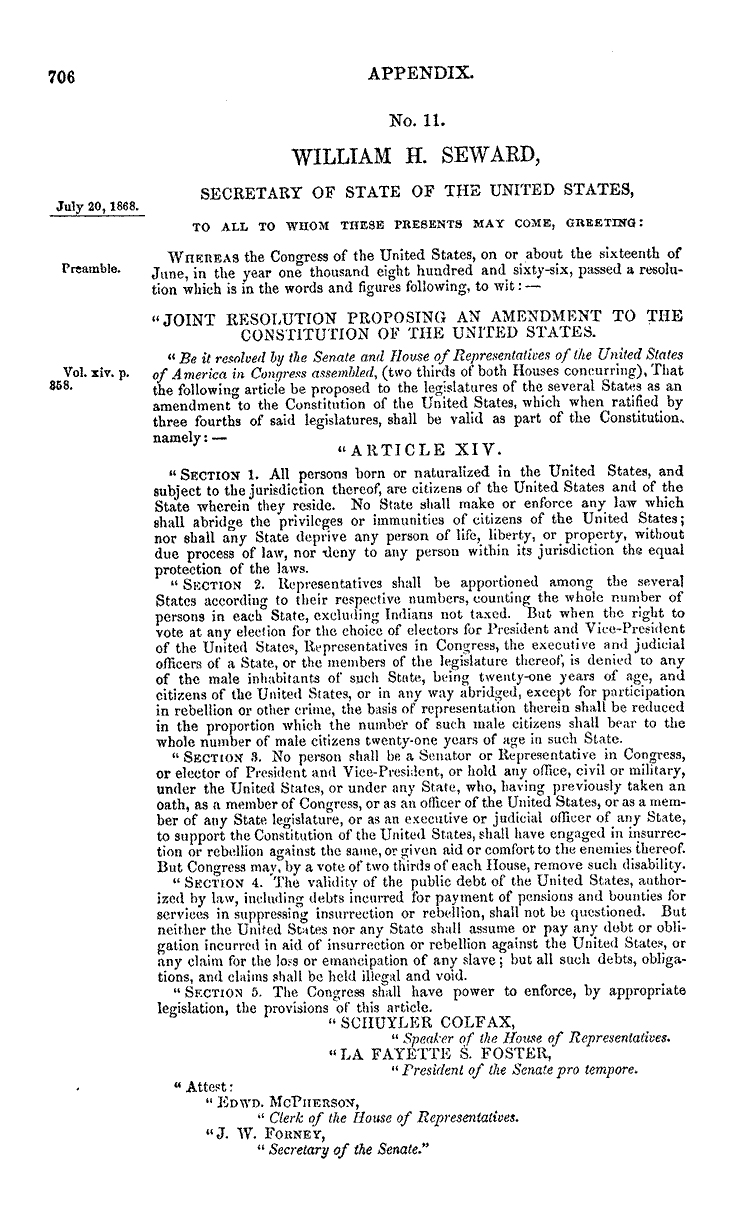

![14th Amendment]()

14th Amendment

The Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution declared that the fed…

-

![15th Amendment]()

15th Amendment

Civil War Reconstruction arguably culminated with the Fifteenth Amendme…

-

![Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon]()

Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon

Oregon's racial makeup has been shaped by three Black exclusion laws th…

-

![Black People in Oregon]()

Black People in Oregon

Periodically, newspaper or magazine articles appear proclaiming amazeme…

-

![First African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church]()

First African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church

First African Methodist Episcopal Zion is Portland's oldest African Ame…

-

![George Putnam Riley (1833–1905)]()

George Putnam Riley (1833–1905)

Identified by the Oregonian as the “Fred[erick] Douglass of Oregon,” Ge…

-

![Mary Laurinda Jane Smith Beatty (1834–1899)]()

Mary Laurinda Jane Smith Beatty (1834–1899)

Mary Beatty, one of the first Black women west of the Mississippi to ad…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

“The Ambition of a Colored Man.” Sunday Oregonian, August 7, 1892.

“Celebration of the 15th Amendment.” Morning Oregonian, April 5, 1870.

“Church Election.” Morning Oregonian, July 7, 1871.

Chused, RIchard H. "Late Nineteenth Century Women's Property Law: Reception of the Early Married Women's Property Acts by Courts and Legislatures." The American Journal of Legal History 29:1 (January 1985): 3-35.

“City—Ratification Jubilee.” Morning Oregonian, April 7, 1870.

Duniway, Abigail Scott. "Married Women's Property Bill." The New Northwest, October 31, 1878.

“The Fifteenth Amendment Jubilee.” Morning Oregonian, April 7, 1870.

“Grand Ratification Jubilee.” Morning Oregonian, April 5, 1870.

Mary L. J. Beatty Estate Record, Multnomah County Record #13611, Case #3855, 1899. Oregon State Archives.

McLagan, Elizabeth. A Peculiar Paradise: A History of Blacks in Oregon, 1788-1940. Portland, Ore.: The Oregon Black History Project and the Georgian Press, 1980.

Nokes, R. Gregory. Breaking Chains: Slavery on Trial in the Oregon Territory. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2013.

Obituary for James W. Beatty. Morning Oregonian, May 7, 1914.

Obituary for James W. Beatty. Oregon Daily Journal, May 9, 1914.

“Ratification of the 15th Amendment.” Morning Oregonian, April 4, 1870.

Richard, K. Keith. “Unwelcome Settlers: Black and Mulatto Oregon Pioneers,” Part l. Oregon Historical Quarterly 84:1 (Spring, 1983): 29-58.

Richard, K. Keith. “Unwelcome Settlers: Black and Mulatto Oregon Pioneers,” Part ll. Oregon Historical Quarterly 84:2 (Summer, 1983): 173-205.

Robbins, Coy E., ed. Indiana Negro Registers 1852-1865. Maryland: Heritage Book, Inc., 1994.

"Women's Property Rights." The New Northwest, April 15, 1880.

"Women's Rights in Law: The Property and Other RIghts of Women in the United States." The New Northwest, January 11, 1878.