In United States v. Tom, the Oregon Territorial Supreme Court questioned the principle of federal supremacy over American Indian affairs in the territory and attempted to establish a standard that, at least in this case, would require Oregon courts to consider the interests of the “white population.” The case provides evidence of the state of mind of white settlers and their leaders during the region’s legal transition from joint occupation to a status as a U.S. territory.

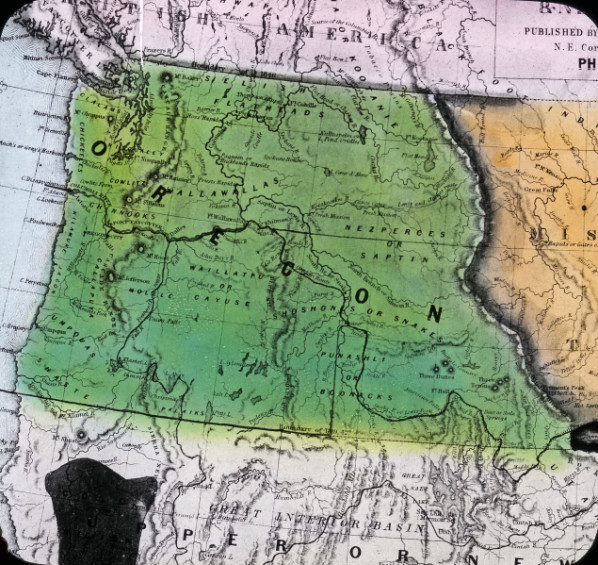

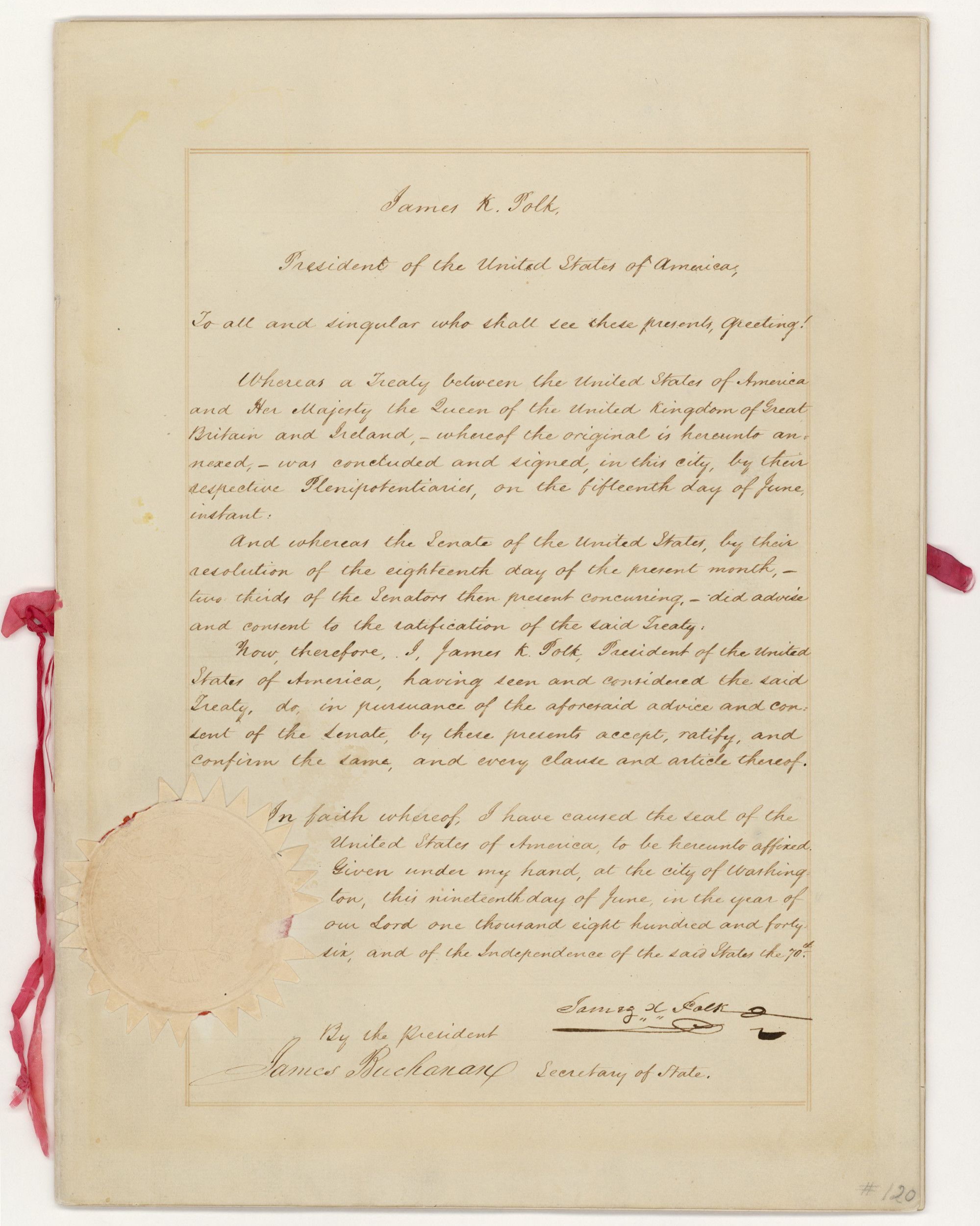

In 1834, Congress passed the Trade and Intercourse Act, Section 20 of which prohibited the sale of “spiritous liquors and wine” in “Indian Country.” At the time, the United States jointly occupied the Oregon Country with Great Britain, and it was not until the Oregon Treaty was signed in 1846 that the U.S. acquired dominion over the region. Two years later, in 1848, Congress established Oregon as a federal territory. The question of Native sovereignty was unclear until 1850, however, when Congress extended federal law over Oregon Territory and required land cessions from tribes to guarantee land titles to non-Natives.

United States v. Tom originated when the U.S. government in 1853 indicted a Native man named “Tom” for selling “a gill of brandy,” valued at twenty-five cents, to another Indian (the indictment did not mention the tribal/national identity of the buyer or seller). Tom’s attorney, D. Logan, moved to quash the indictment on the grounds that Oregon Territory was not “Indian Country” when the 1834 prohibition law was enacted and that the United States did not have jurisdiction to charge Tom. The Clackamas County district court adjourned the case until the territorial supreme court could consider the motion.

The court overruled the motion and upheld the indictment. In his majority opinion, Chief Justice George Henry Williams argued that Congress had not intended to apply federal law west of the Rocky Mountains at the time of the 1834 statute, and he agreed with Tom's counsel that Oregon was not included in the “Indian Country” set out in the statute. Williams noted, however, that Congress had extended the law over Oregon in 1850 and maintained, without any authority to support his ruling, that Congress had left the territorial government with the power to determine which provisions of the Trade and Intercourse Act would be “applicable.” The question, he wrote, was whether the alcohol regulations in the act had been extended over Oregon by the act passed in 1850 and which body possessed the power to answer that question. Williams held that the Oregon Territorial Supreme Court had the authority to make that determination.

The chief justice then asserted that the appropriate test for the court was whether the provision benefitted “the true interests of the white population.” He concluded that Section 20 was applicable because “defenseless white persons, women and children, are exposed to the violence of drunken savages” and require protection. The prohibition of alcohol in the territory was “a blessing to the Indians, and highly promotive to the safety, peace, and good order of the whole community.” He also declared, in dicta, that federal provisions that prevented immigration or “the free occupation and use of the country by whites” would be repealed. “Whatever militates against the true interests of a white population,” he concluded, “is inapplicable.”

Justice Cyrus Olney, departing from Williams, maintained that the relevant question was whether the Trade and Intercourse Act interfered with the right of territorial residents to import and sell goods, including alcohol. “Whites” possessed “rights of unrestrained traffic with the Indians” that existed prior to the 1834 act, Olney explained, and federal laws that conflicted with those rights “must give way” to “the rights of the whites.” Neither justice noted that it was not a “white” but a Native who had been indicted for the sale. Justice Obadiah B. McFadden argued in his opinion that Congress intended for the alcohol regulations to be applied in Oregon and that it would be in the best interests of the people of the territory, white and Native, for the federal government to enforce the provisions.

In 1855, George W. Manypenny, the U.S. commissioner of Indian Affairs, asked U.S. Attorney General Caleb Cushing to review the Tom decision. Cushing not only repudiated the decision, but he also belittled Chief Justice Williams’s characterization of the conflict as complicated. “The question is a very simple one,” Cushing wrote, “and cannot be drawn in doubt except by complete disregard of all the rules of statutory construction, and of the whole theory and system of the Government.”

Cushing maintained that Article 14 of the 1848 Organic Act extended all of the laws of the United States over the territory, including the Trade and Intercourse Act of 1834. He described the Oregon court’s applicability standard as a “very strange idea”: “‘Applicability’ in a law has nothing to do with the question whether the persons to whom it is to be applied think it for their interest. That question Congress determines.” Cushing argued that such a rule would make a “singular patchwork of the acts of Congress” and “nullify all the acts of Congress by piecemeal in one-half the States or Territories of the Union, some here and some there, according to the local estimation of their interests on the part of the inhabitants of this or that State or Territory.” He concluded: “Such a doctrine is of course untenable.” The applicability of federal laws, Cushing wrote later in the opinion, did not depend on whether they were “beneficial to the whites”: “To decide that laws are applicable when they please the fancy of those against whom they are passed….would be to abolish law.”

Cushing rejected the Oregon court’s declaration that the territory was not “Indian country,” noting that it was “a part of the United States, west of the Mississippi,” as defined in the Trade and Intercourse Act, and that the question had been settled by the 1850 territorial act. The Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution, he wrote, endowed Congress with “the power to regulate commerce with the Indian tribes,” and the Supremacy Clause made federal statutes the supreme law of the land. Any effort to modify federal law by the territorial government of Oregon or its courts would be null and void.

Cushing concluded by attacking the suggestion that white Oregonians could take Native lands before their Indian title had been extinguished: “This idea is too absurd to admit of reasoned reply. Suffice to say that a white settler has the same right thus to oust the Indians as he has to oust white men, and no more; that is, the right to substitute robbery for purchase, and violence for law.”

There is no record what happened to Tom or the Tom case after Cushing dismissed the Oregon court’s interpretation of how and whether federal law could be applied in Oregon Territory. It is likely, because the 1834 act was upheld in Cushing’s review, federal authorities followed through and convicted Tom of the offense.

-

![]()

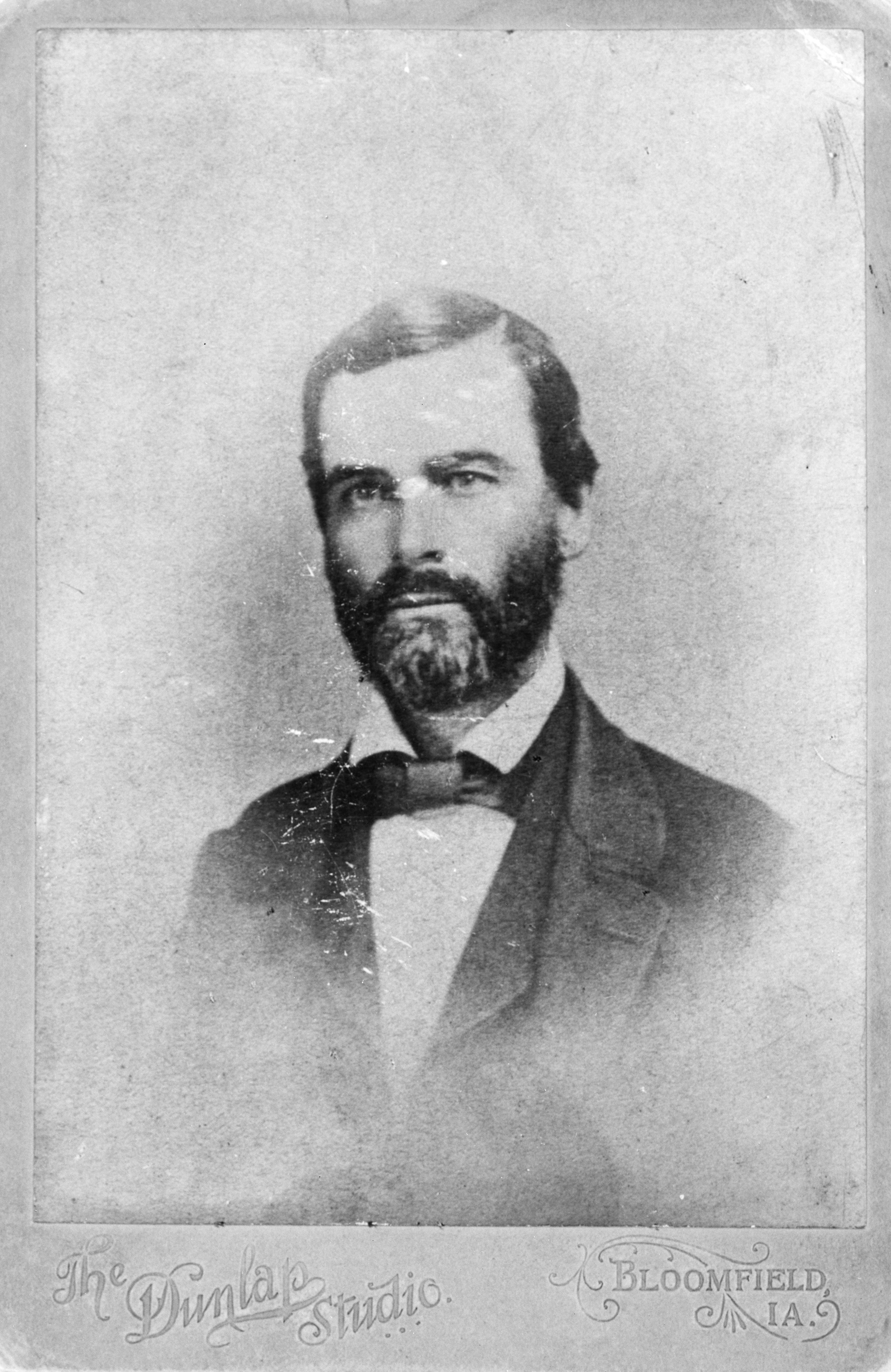

Judge Obadiah McFadden.

Courtesy Library of Congress -

![Cyrus Olney presided at Charity Lamb's trial.]()

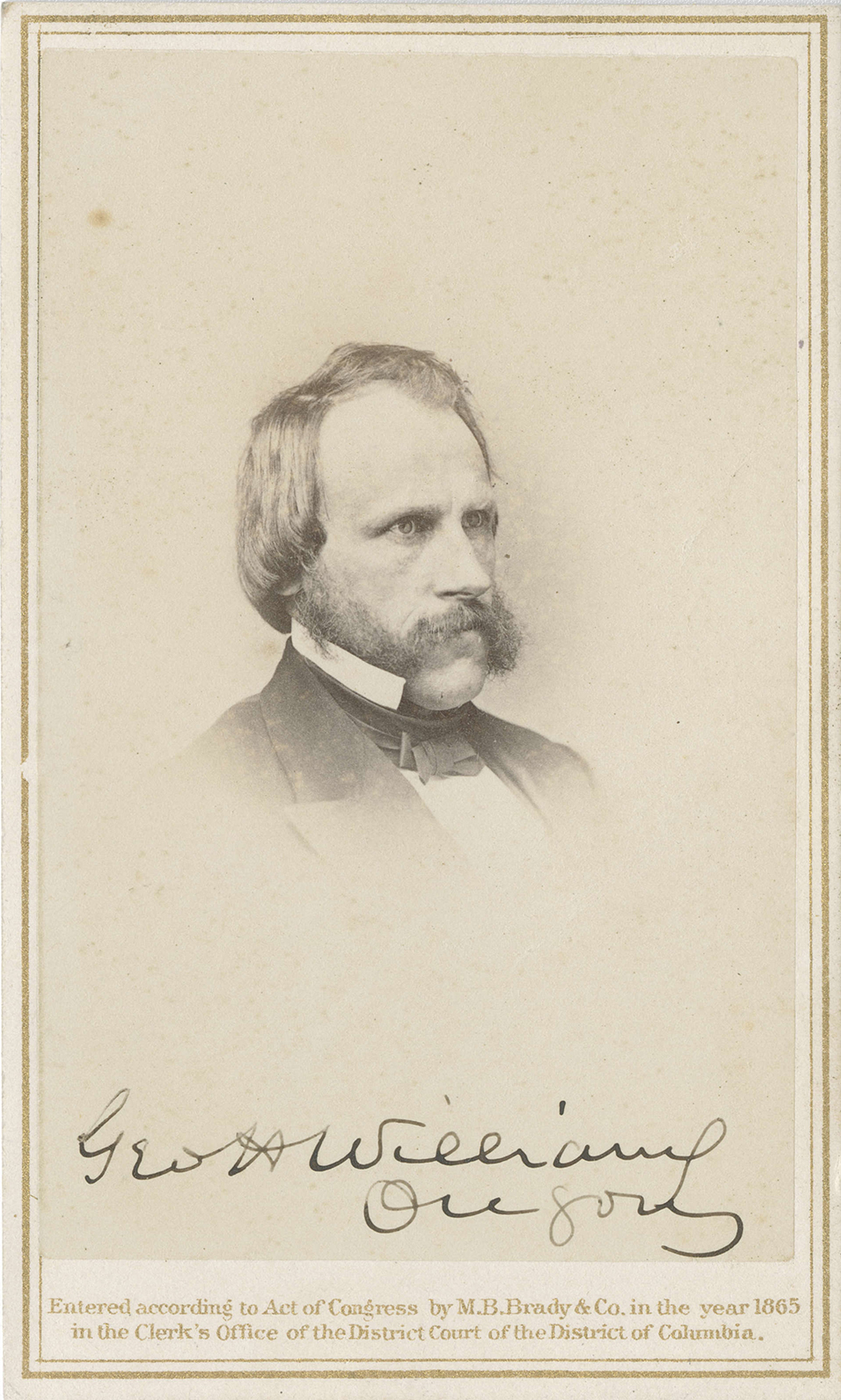

Olney, Cyrus, bb007125.

Cyrus Olney presided at Charity Lamb's trial. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb007125

-

![]()

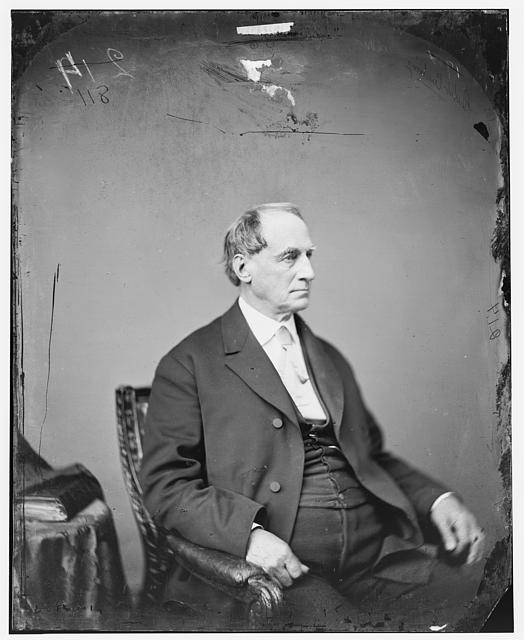

George H. Williams, 1865.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, OrgLot500_1122_A_1 -

![]()

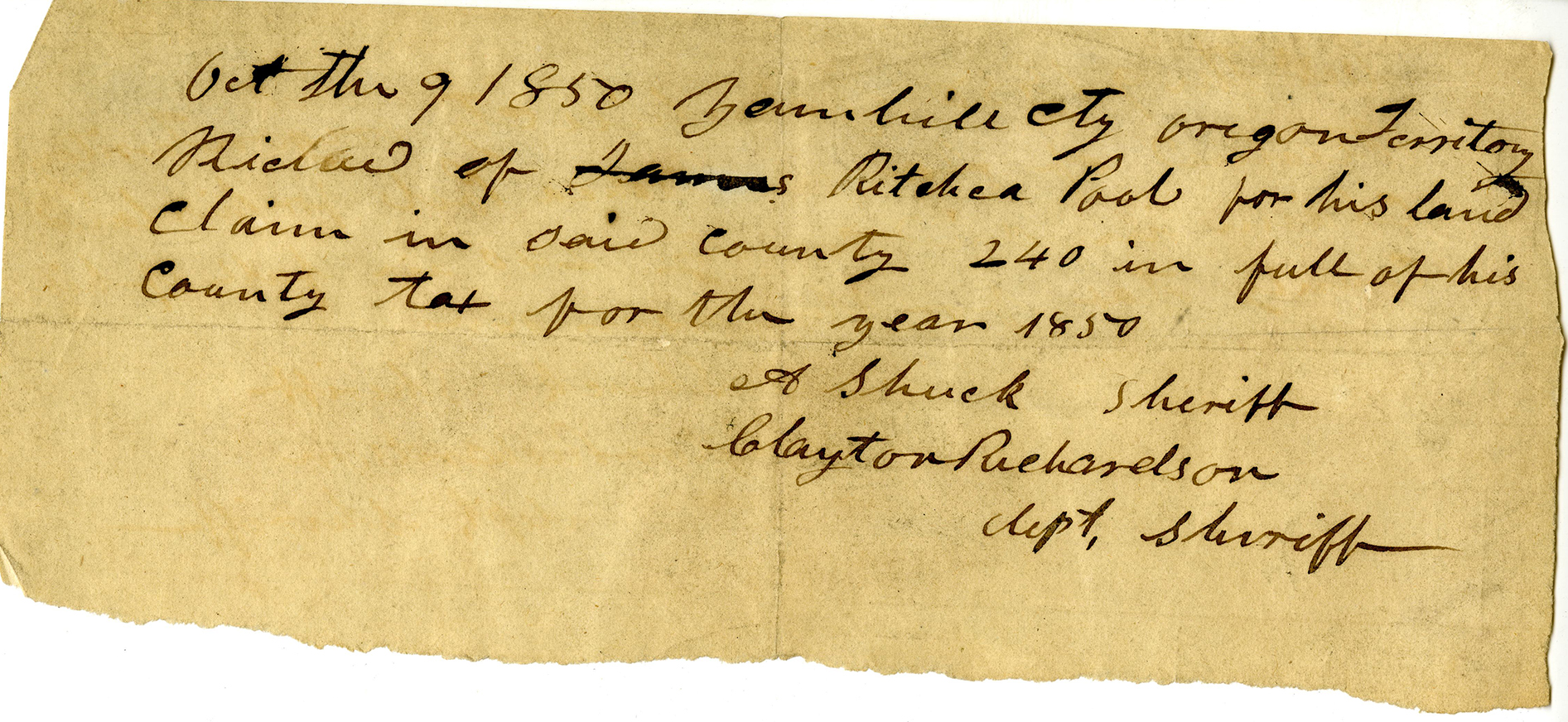

Caleb Cushing.

Courtesy Library of Congress

Documents

Related Entries

-

![George H. Williams (1823–1910)]()

George H. Williams (1823–1910)

George H. Williams was a Democratic politician and officeholder in Oreg…

-

![Oregon Donation Land Law]()

Oregon Donation Land Law

When Congress passed the Oregon Donation Land Law in 1850, the legislat…

-

![Oregon Question]()

Oregon Question

“The Oregon boundary question,” historian Frederick Merk concluded, “wa…

-

![Oregon Treaty, 1846]()

Oregon Treaty, 1846

On November 12, 1846, the Oregon Spectator announced that Captain Natha…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Cushing, Caleb. "Indians in Oregon." Official Opinions of the Attorneys General of the United States 7 (1854-1856): 293-299.

Foster, Hamar and Alan Grove. “‘Trespassers on the Soil’: United States v. Tom and A New Perspective on the Short History of Treaty Making in Nineteenth-Century British Columbia.” BC Studies 138/139 (Summer/Autumn 2003): 51-84.

Harring, Sidney L. Crow Dog’s Case: American Indian Sovereignty, Tribal Law, and United States Law in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge University Press, 1994), 212-220.

Niedermeyer, Deborah. “The True Interests of a White Population: The Alaska Indian Country Decisions of Judge Matthew P. Deady,” New York University Journal of International Law and Politics 21 (1) (Fall 1988): 195-258.

United States v. Tom, 1 Or. 27 (1853), 26-31.