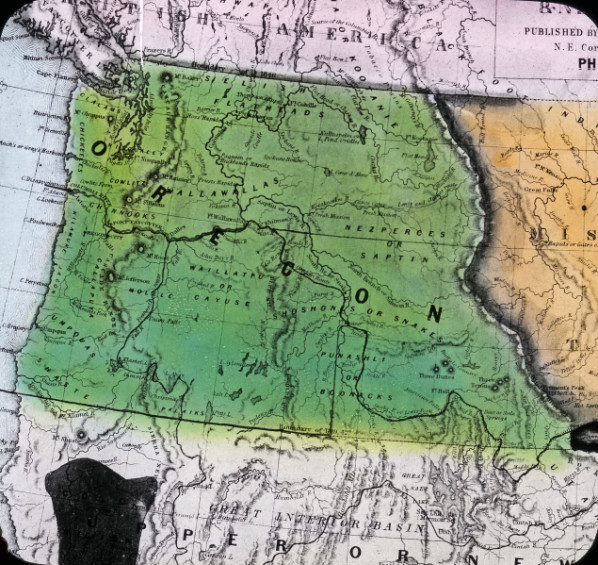

On November 12, 1846, the Oregon Spectator announced that Captain Nathaniel Crosby of the American barque Toulon had arrived from Hawaii, bringing news of the signing of a treaty with Great Britain over the fate of the Oregon Country. Signed in Washington, D.C., on June 15, the Oregon Treaty ended a “Joint Occupancy” of twenty-eight years over an expansive region that stretched from present-day southeast Alaska to the Rocky Mountains on the east and the 42nd parallel on the south. It settled the Oregon Question, the resolution of which portions of the territory each nation could rightfully claim, and it set the 49th parallel as the northern limit of American sovereignty in the Pacific Northwest.

The history of the contending claims made by the two nations on the Pacific Northwest resulted from a bilateral treaty in 1818—part of international settlements of claims subsequent to the War of 1812—which allowed equal opportunity for occupation and economic activities, but not sovereignty. That agreement, originally set for ten years, became the subject of multiple diplomatic discussions after 1827, until geopolitical conditions in the 1840s forced both nations to find a mutual resolution. At stake for Britain was the fate of its powerful Hudson’s Bay Company in the Pacific Northwest and control of Puget Sound ports and navigation on the Columbia River. At stake for the United States was the prospect of an American preemptive attempt at sovereignty through the Oregon Provisional Government in 1843, an illegal government that had grown in importance as thousands of overland emigrants settled in the Willamette Valley.

The question of which national flag would fly exclusively over Oregon was answered in diplomacy, but not before several years of argument and saber-rattling by British and American governments. In 1827, after less than a decade of the joint occupation, neither nation was prepared to create a solution to what became known as the Oregon Question, or how the region would be partitioned. Instead, they left open a future resolution, allowing either party to nullify the previous agreement with a one-year notice. By then, however, the sides had established hard choices and were at odds: Britain had been resolute in demanding that the Columbia River would be the partition line, thereby enclosing agricultural land and Puget Sound in present-day Washington State, while the U.S. argued for partition at the 49th parallel, the established boundary between the U.S. and Canada east of the Rockies, that extended to Puget Sound, with navigation rights shared in the Sound. By 1842, when Britain and the U.S. settled the disputed boundary between Maine and Canada—the Webster–Ashburton Treaty—some hoped the Oregon Question would be included, but both nations ignored Oregon and put off a resolution.

By 1843, American migration to the Oregon Country had increased the pressure to solve the Oregon Question. The next year, President John Tyler changed the debate by extending the American claim potentially to 54° 40’ in present-day Canada, the “all of Oregon” solution. In March 1845, Tyler’s successor, James K. Polk, called the American claim on Oregon “clear and unquestionable.” In July, however, the president offered a boundary at the 49th parallel as a compromise. Britain’s ambassador to Washington flatly rejected it, prompting some British politicians to support using military force to defend their nation’s interests in the Pacific Northwest.

By early January 1846, political conditions in Britain and the United States began to change once again, and war talk quieted. The London Times editorialized in favor of entertaining the American solution, even as U.S. expansionists bellowed “Fifty-four Forty or Fight” to stiffen Polk’s resolve. Polk had not campaigned on the issue and never used the phrase before winning election in 1844, but he let the threat linger in hopes that his compromise would find favor in London.

During the spring of 1846, economic interest groups in both nations argued for compromise on the fate of Oregon. The Hudson’s Bay Company, for example, moved its regional headquarters to Victoria on Vancouver Island in 1845. In late 1845, some British politicians proposed repealing the restrictive Corn Laws tariffs on agricultural commodities to improve economic conditions. American politicians, especially from the South, hailed the effort, expecting the prospect of selling their produce to England. In May, the repeal succeeded on the eve of treaty discussions on Oregon in Washington, D.C.

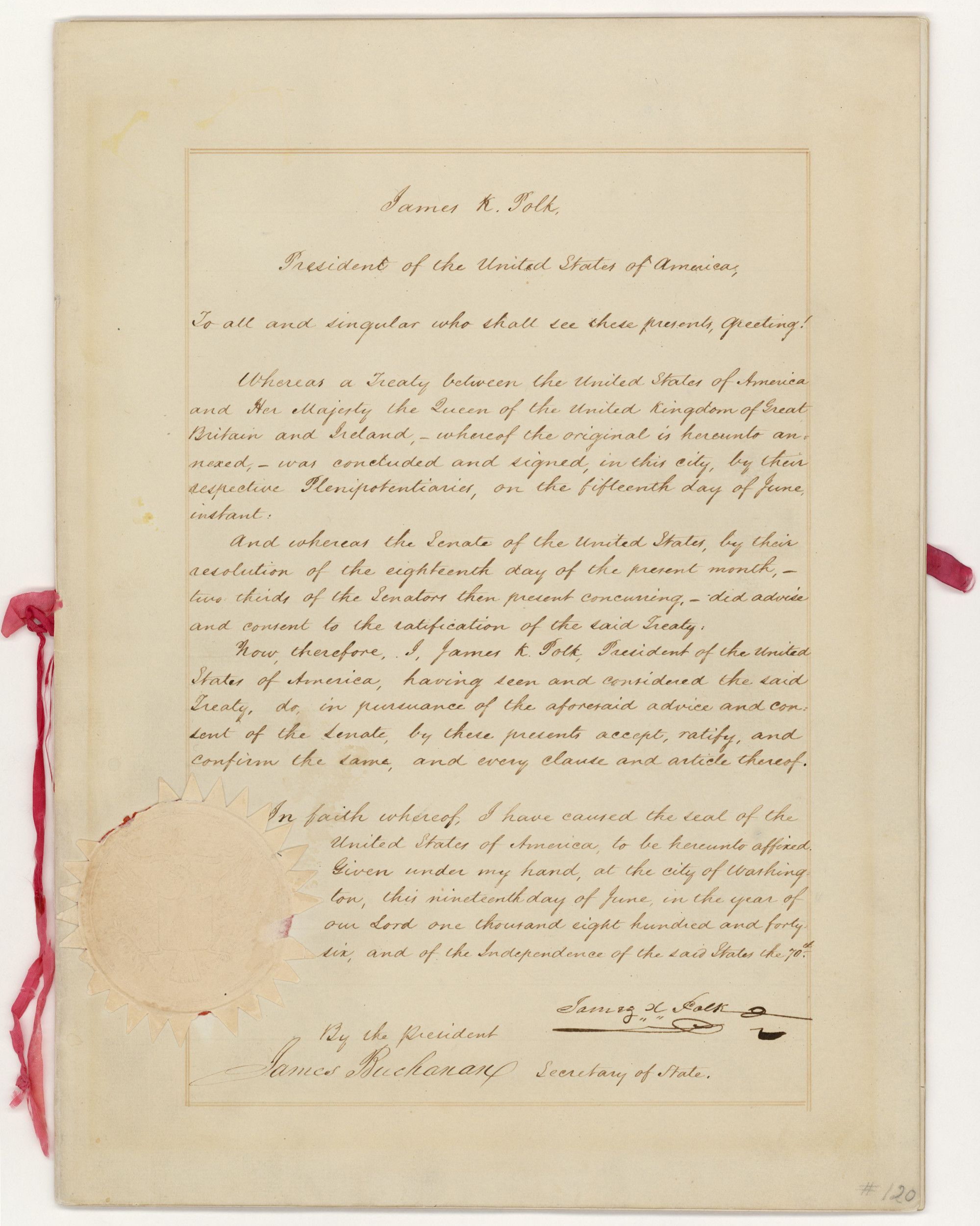

In early June 1846, Secretary of State James Buchanan met in Washington, D.C., with the British ambassador to the U.S., Richard Packenham, each with instructions to find a resolution. The British response to Polk’s final conditions reached the capital city on June 6. Within just over a week the negotiators had finished the treaty, which included four main articles. The first partitioned the Oregon Country at the 49th parallel stretching from the Rockies to the middle of Puget Sound and ensuring common navigation rights in the Sound for both nations. The second article guaranteed open navigation of the Columbia River for the Hudson’s Bay Company and British subjects. Article three provided that property held by HBC and British subjects in the area south of the 49th parallel “shall be respected.” The fourth article protected the agricultural operations of HBC’s Puget Sound Agricultural Company north of the Columbia River. The negotiators signed the treaty on June 15, 1846, and the U.S. Senate approved it on June 18. The British Parliament received the text on June 28 and subsequently approved the agreement.

Two issues were left for future agreements. The value and resolution of claims against HBC property in Oregon became the basis for several legal disputes, all of which were resolved by 1869; and the precise demarcation of the boundary between U.S. and future Canadian possessions in Puget Sound was settled by an international arbitration in 1872.

-

![]()

Oregon Treaty.

Courtesy National Archives -

![]()

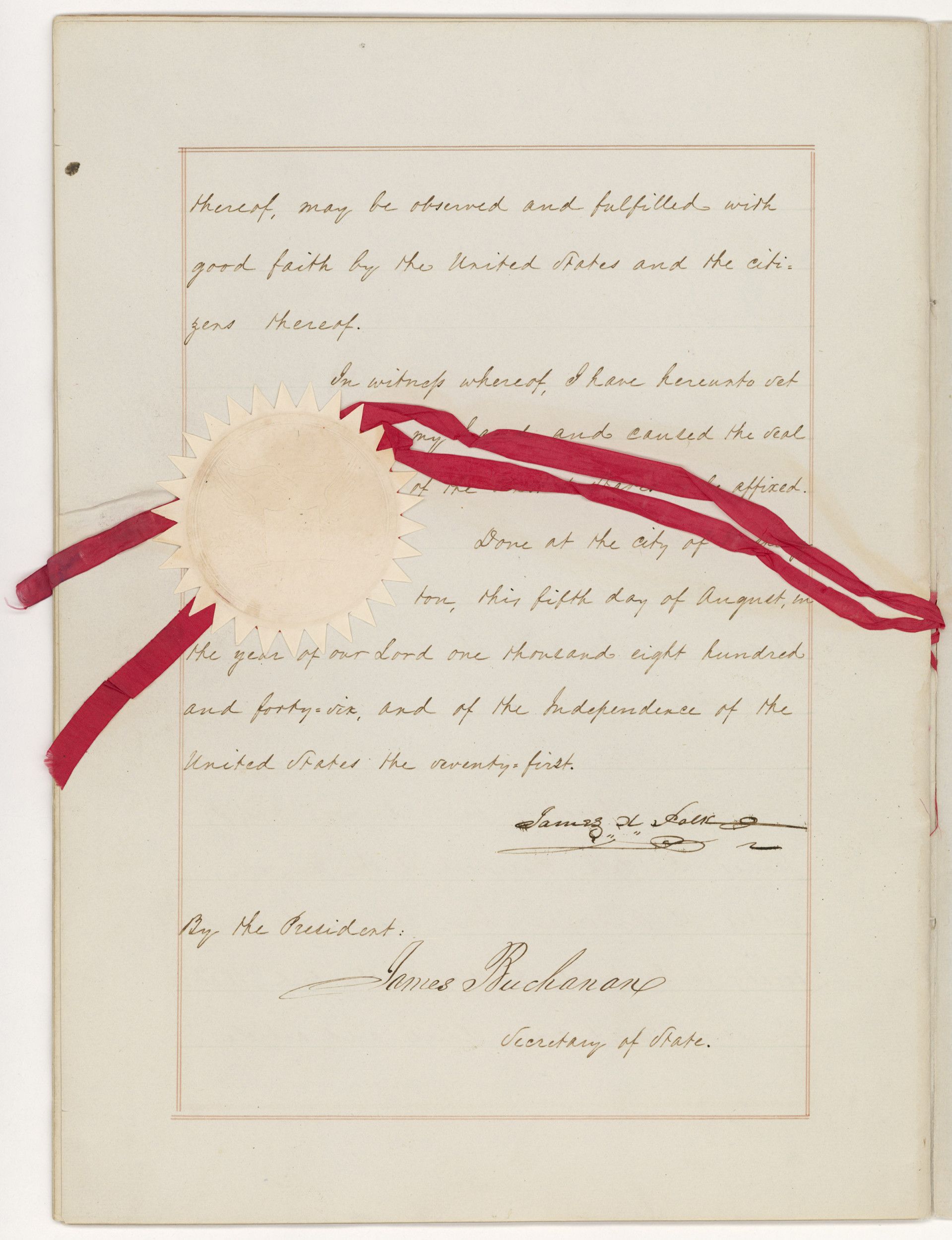

Oregon Treaty.

Courtesy National Archives

Related Entries

-

![Columbia River]()

Columbia River

The River For more than ten millennia, the Columbia River has been the…

-

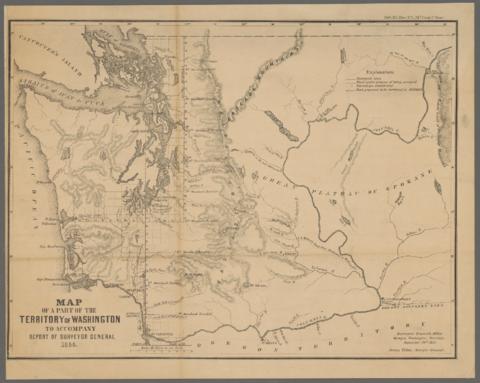

![Creation of Washington Territory, 1853]()

Creation of Washington Territory, 1853

On August 14, 1848, Congress created Oregon Territory, a vast stretch o…

-

![Hudson's Bay Company]()

Hudson's Bay Company

Although a late arrival to the Oregon Country fur trade, for nearly two…

-

![Oregon Question]()

Oregon Question

“The Oregon boundary question,” historian Frederick Merk concluded, “wa…

-

![Provisional Government]()

Provisional Government

The Provisional Government, created in May-July 1843, was the first gov…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Cramer, Richard S. “British Magazines and the Oregon Question.” Pacific Historical Review (November 1963): 369-382.

Horsman, Reginald. Race and Manifest Destiny. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Press, 1981.

Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848. New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 2007.

McClintock, Thomas C. “British Newspapers and the Oregon Treaty of 1846.” Oregon Historical Quarterly (Spring 2003): 96-109.

Martig, Ralph Richard. “Hudson’s Bay Company Claims, 1846-1869.” Oregon Historical Quarterly (March 1935): 60-70.

Merk, Frederick. History of the Westward Movement. New York: Knopf, 1978.

Miles, Edwin A. “’Fifty-four Forty or Fight’—An American Political Legend.” Mississippi Valley Historical Review (September 1957): 291-309.