Located some three-miles east of Astoria, Oregon, the Tongue Point Naval Air Station—named for the one-mile-long tongue-shaped peninsula that it once occupied—was commissioned in December 1940, making it the first of several primary and auxiliary naval air stations established in Oregon during World War II. As of late 2025, the repurposed installation is home to a Job Corps campus.

Jutting northward from the Oregon side of the Columbia River, Tongue Point’s prominent shape and location drew the attention of both Natives and EuroAmericans. According to historian Silas B. Smith, the Chinookan name for the peninsula is Secomeetsiuc. Lt. William Broughton, from the George Vancouver expedition, dubbed it Tongue Point in 1792, referring to it as “a remarkable projecting point…on the southern shore, appearing like an island.”

The feature’s commanding position near the river’s central channel led the Canadian fur-trading North West Company to establish fortifications there in 1814, hoping to create a “Gibraltar of the West.” For reasons unclear, however, the station was abandoned for Fort George (formerly Fort Astoria).

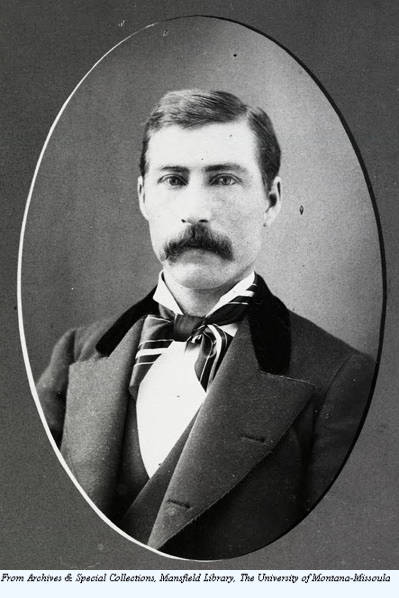

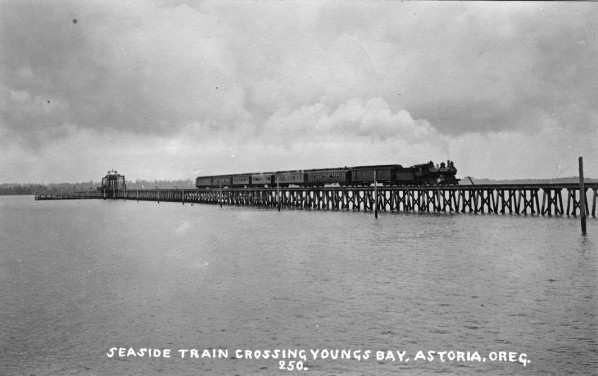

By the late nineteenth-century, Tongue Point had become an important location along lumberman A.B. Hammond’s newly-built Astoria and Columbia River Railroad. The site included a large sawmill that produced a staggering 250,000 feet of lumber per shift. The western side of the peninsula concurrently served as a buoy depot for the U.S. Lighthouse Board.

In the years prior to and during World War I, the U.S. War Department considered Tongue Point for destroyer, submarine, and aviation service. Astoria experienced fewer fog days than comparable installations in San Francisco and Los Angeles, favoring aviation maneuvers. The peninsula was also protected by the Harbor Defense Command of the Columbia River (consisting of Forts Stevens, Canby, and Columbia), and the point’s position upriver from the Columbia Bar provided a degree of safety from naval gunfire.

Enticed by the economic growth and prestige that could come with a naval installation, Clatsop County residents voted in 1921 to purchase Tongue Point for $100,000 from seven different owners, including Hammond and the Columbia Land Company. The land was then donated to the U.S. Navy, which dredged and constructed a series of piers on the peninsula’s east side to create a submarine base. Work halted, however, when congressional funding ran dry and Navy Secretary Curtis Wilbur, after visiting Astoria in summer 1925, soured on any further development at Tongue Point.

During the 1930s, Japanese expansion into the western Pacific spurred a rededication to national defense. Concerns over the unprotected beaches from Coos Bay to Grays Harbor breathed new life into the Tongue Point project. The base’s strongest champion was the Columbia Defense League, formed in 1934 by a group of politicians, business leaders, and boosters to bring attention to the Columbia River estuary’s strategic importance and vulnerability to attack.

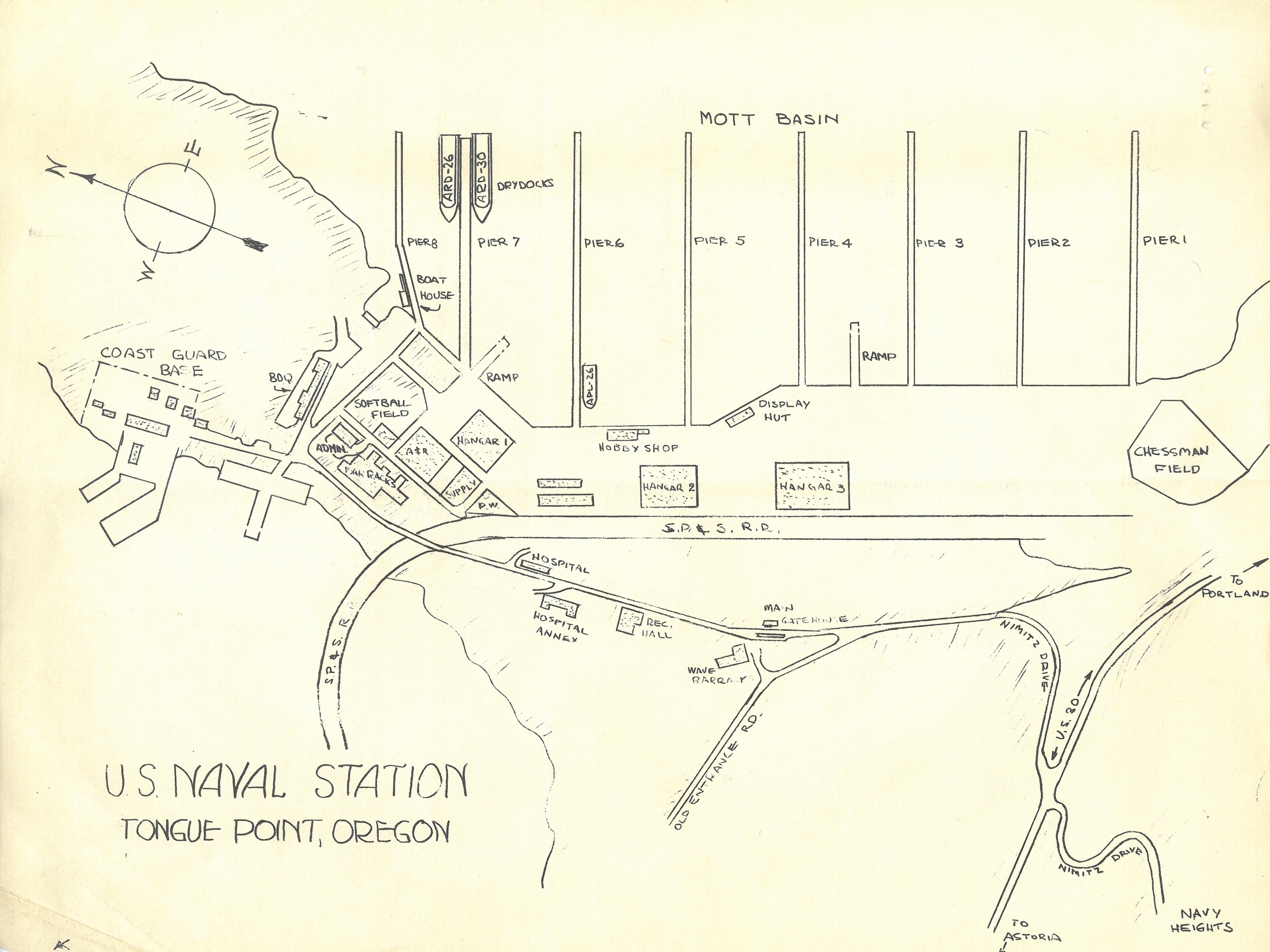

Tongue Point Naval Air Station was finally dedicated on August 31, 1939, just one day before Germany invaded Poland. With a budget of $1.5 million, the Navy began construction on hangars to support up to thirty-six PBY Catalina seaplanes, three seaplane ramps, barracks and officers’ quarters for 3,000 personnel, and additional finger piers along Cathlamet Bay. As the Navy transitioned from seaplanes to ground-based aircraft for patrolling, it considered extending Tongue Point into the Columbia River for runway space. Instead, it was faster and cheaper to improve the Clatsop County Airport, nearly seven miles to the southwest. The upgrade was completed in 1942 for $4.6 million. Naval aviators trained and flew patrols out of the revamped airport while sailors at Tongue Point were instructed in radar, ordnance, communications, supply, and aircraft repair. By spring 1944, Tongue Point, Clatsop County Airport, and Moon Island Airport at Hoquiam, Washington, all fell under the designation "Naval Air Station Astoria."

But for one report of a Japanese balloon bomb sighting and the June 1942 shelling of nearby Fort Stevens, the shooting war never got close to Tongue Point. Among the installation’s most notable wartime contributions was the training of aviators and flight crews for fifty new Casablanca-class escort carriers built at Vancouver’s Kaiser Shipyards and finished in Astoria. These “Baby Flat Tops”—smaller versions of the Navy’s Essex class carriers—went on to serve at Leyte Gulf, Lingayen Gulf, Okinawa, and Iwo Jima.

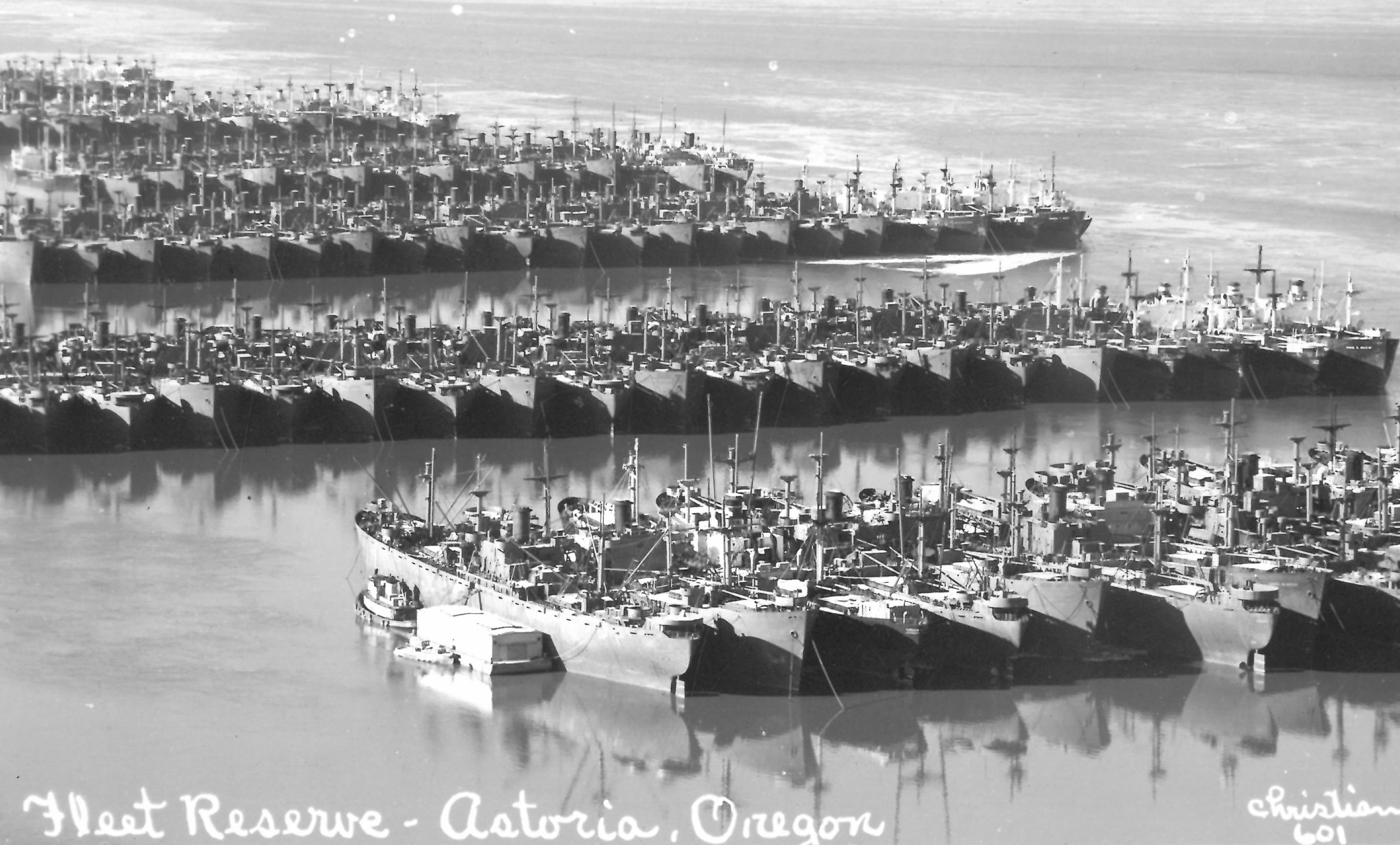

The base’s freshwater port was ideal for long-term moorage, and Tongue Point became responsible at war’s end for activating, maintaining, and deactivating hundreds of ships of the Pacific Reserve Fleet. Civilian contractors came from Portland, Astoria, and Seattle to find work at the installation, most residing at the 368-unit Navy Heights or 102-unit Tongue Point village, both located to the base’s immediate south.

By 1957, the base’s role diminished to stewardship over a handful of ships, and the Navy declared it surplus in 1961. Oregon Representative Walter Norblad lobbied in 1963 to convert the facility to a NASA Electronic Research Center, and Astoria Mayor Harry Steinbock launched a one-person campaign in the 1970s to make Tongue Point home to the Navy’s new Ohio-class ballistic missile submarine. But like so many decommissioned postwar installations, Tongue Point was instead repurposed to civilian use. A Job Corps training center was opened in 1965, graduating thousands of students in various trades, ranging from welding to seamanship. With the Federal Government’s May 2025 order to close Job Corps campuses nationwide and subsequent litigation, Tongue Point station’s status is unclear.

-

![]()

Tongue Point with Cathlamet Bay in the foreground, 1935.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Photo File #59

-

![]()

A Tongue Point-based Curtiss Helldiver soars over the facility in August 1945.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Photo File #59

-

![]()

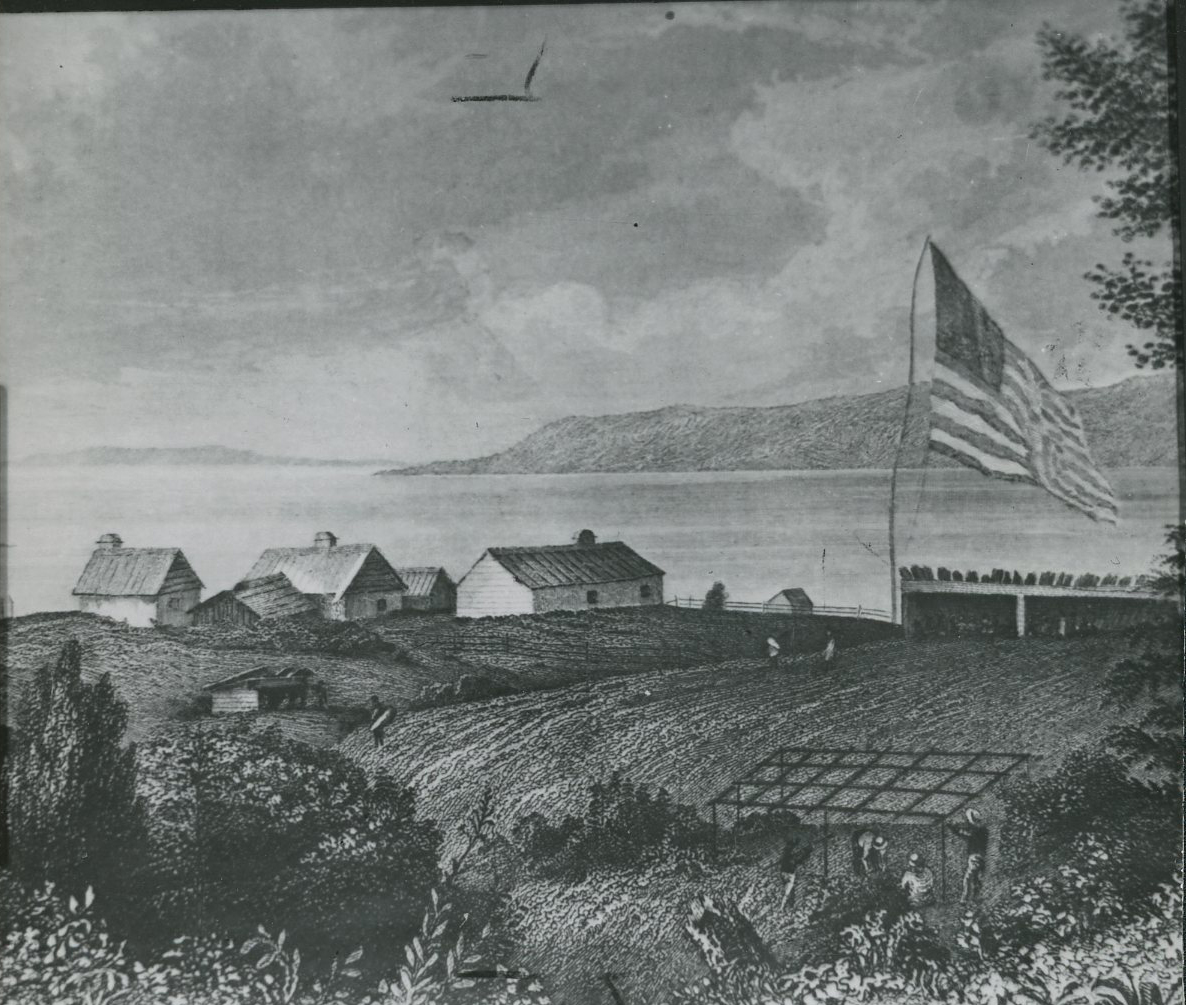

Artistic rendering of Tongue Point in 1883 by Cleveland Rockwell.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Photo File #59

-

![]()

Motor tourists make their way by a still demilitarized Tongue Point, c. 1918.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Photo File #59

-

![The U.S.S. Kalinin eventually came to Tongue Point and then to the war in the Pacific.]()

Escort carrier U.S.S. Kalinin's launch at Kaiser’s Vancouver Shipyard.

The U.S.S. Kalinin eventually came to Tongue Point and then to the war in the Pacific. Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Photo File # 2212

-

![]()

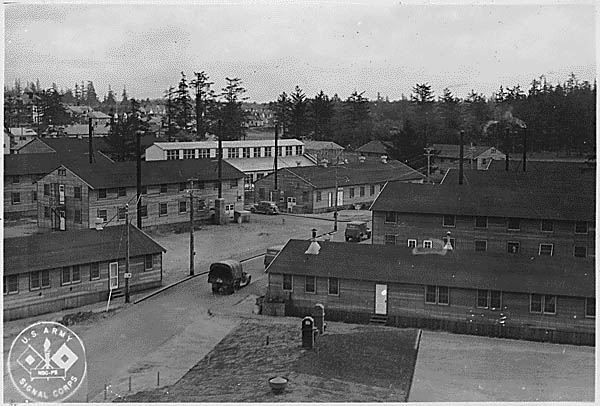

Tongue Point Naval Air Station with Mott Basin in the foreground, 1946.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Photo File #59

-

![]()

Base personnel stand for inspection at Tongue Point Naval Air Station, September 1947.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Photo File #59

-

![]()

Tongue Point Naval Air Station and Mott Basin, November 1949.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Photo File #59

-

![]()

Several navy ships line Tongue Point’s Mott Basin, c.1950.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Photo File #59

-

![]()

Tongue Point Naval Air Station map, 1956 map .

-

![]()

President John F. Kennedy visits Tongue Point in September 1963.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Oregonian Photographs Collection, Org. Lot 1359, Box 29, Folder 29

Related Entries

-

![Andrew B. Hammond (1848-1934)]()

Andrew B. Hammond (1848-1934)

Sensing opportunity following the Panic of 1893, Montana businessman An…

-

![Astoria and Columbia River Railroad]()

Astoria and Columbia River Railroad

Ever since Astoria was founded at the mouth of the Columbia River in 18…

-

![Balloon Bombs]()

Balloon Bombs

The Mitchell Monument marks the spot near Bly, Oregon, where six people…

-

![Columbia River]()

Columbia River

The River For more than ten millennia, the Columbia River has been the…

-

![Fort George (Fort Astoria)]()

Fort George (Fort Astoria)

Fort George was the British name for Fort Astoria, the fur post establi…

-

![Fort Stevens]()

Fort Stevens

One of the three major forts designed to protect the mouth of the Colum…

-

![George Vancouver (1757-1798)]()

George Vancouver (1757-1798)

The role George Vancouver played in Oregon history is tangential, yet i…

-

![Kaiser Shipyards]()

Kaiser Shipyards

During World War II, industrialist Henry J. Kaiser established three sh…

-

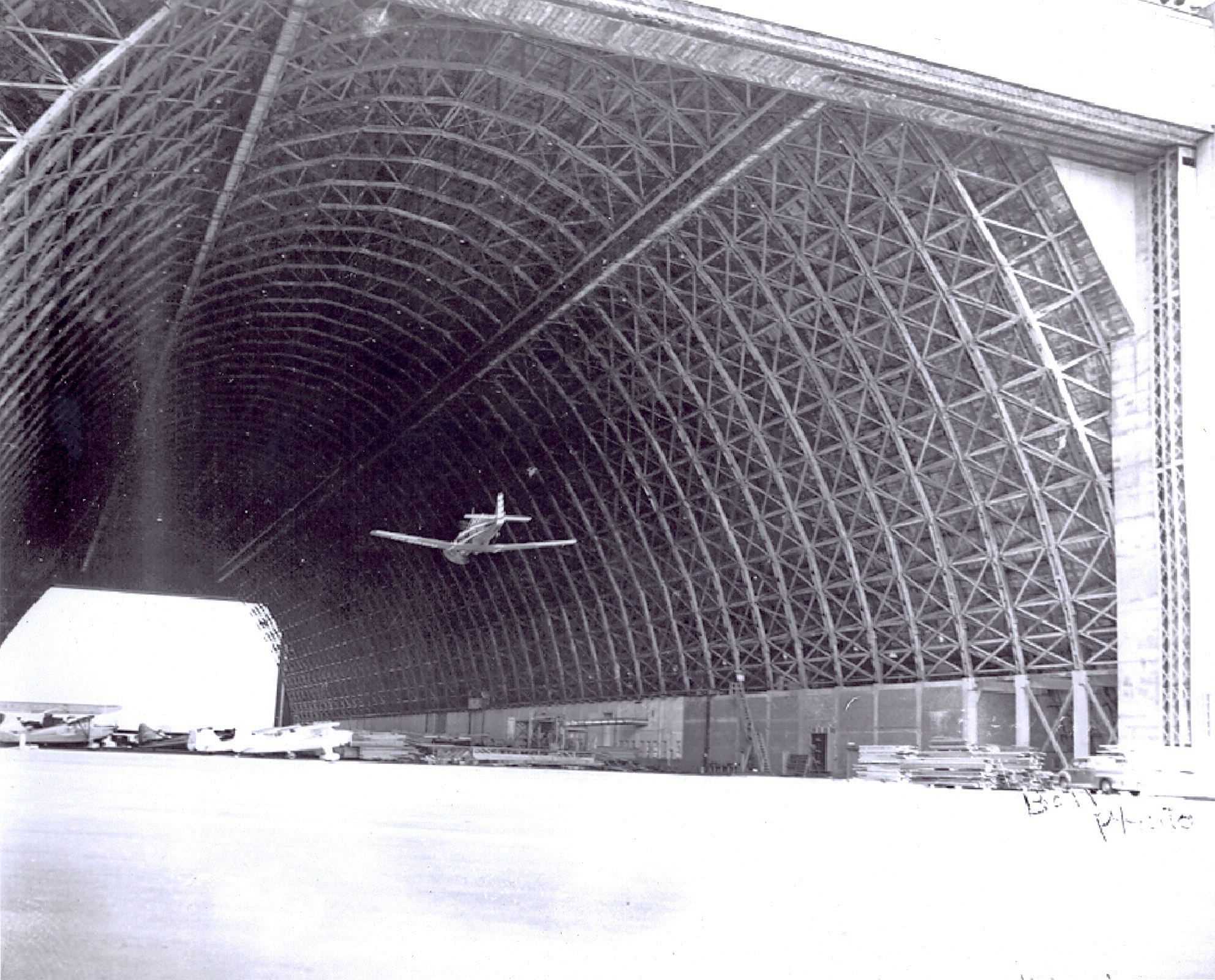

![Naval Air Station Tillamook / Tillamook Air Museum]()

Naval Air Station Tillamook / Tillamook Air Museum

Tillamook is home to the largest free-standing, clear-span wooden struc…

-

![The Beach Patrol in Oregon, U.S. Coast Guard, 1942-1944]()

The Beach Patrol in Oregon, U.S. Coast Guard, 1942-1944

The Beach Patrol in Oregon, which kept watch over the Oregon coastline …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Lyman, H.S. “Indian Names.” Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society 1.3 (September 1900): 321.

Wood, T.B. “Letters of Tallmadge B. Wood.” Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society 4.1 (March 1903): 82.

Simpson, George, and Peter Skeen Ogden, et al. “Secret Mission of Warre and Vavasour.” Washington Historical Quarterly 3.2 (April 1912): 139.

Ruby, Robert H., and John A. Brown. The Chinook Indians: Traders of the Lower Columbia. Norman: Oklahoma University Press, 1976.

Frederick Steiwer Papers, 1903-1938. Mss 1496, Box 8, Folder 15. Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Portland.

“Astoria, Enfete, Has No Middies.” Portland Oregonian, July 21, 1925.

Kann, Steve, and Janet Kann. “World War II Civilian Defense.” Cumtux: Clatsop County Historical Society Quarterly 11.2 (Spring 1991): 31-32.

Dierdorff, John. “Backstage with Frank Branch Riley, Regional Troubadour,” Oregon Historical Quarterly 74.3 (September 1967): 215.

"Tongue Point: Story of the Fleet That Didn’t Come to Stay.” Portland Oregonian, September 16, 1963.

Godson, Susan H. “Astoria, Ore., Naval Air Station, 1940-1946.” In United States Navy and Marine Corps Bases, Domestic, edited by Paolo E. Coletta and K. Jack Bauer. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985.

“U.S. Naval Base at Tongue Point Mighty Fortress.” Albany Democrat-Herald, September 1, 1945.

“Job Corps Cheers Golden Anniversary.” Daily Astorian, February 10, 2015.