Before there was Gideon v. Wainwright or an Oregon public defender, there was Irvin Goodman. From the late 1920s until his death in 1958, Goodman represented communists, union leaders, a Soviet naval officer charged with espionage, immigrants facing deportation, Black defendants facing the death penalty, and many others who encountered an often uncaring and biased court system.

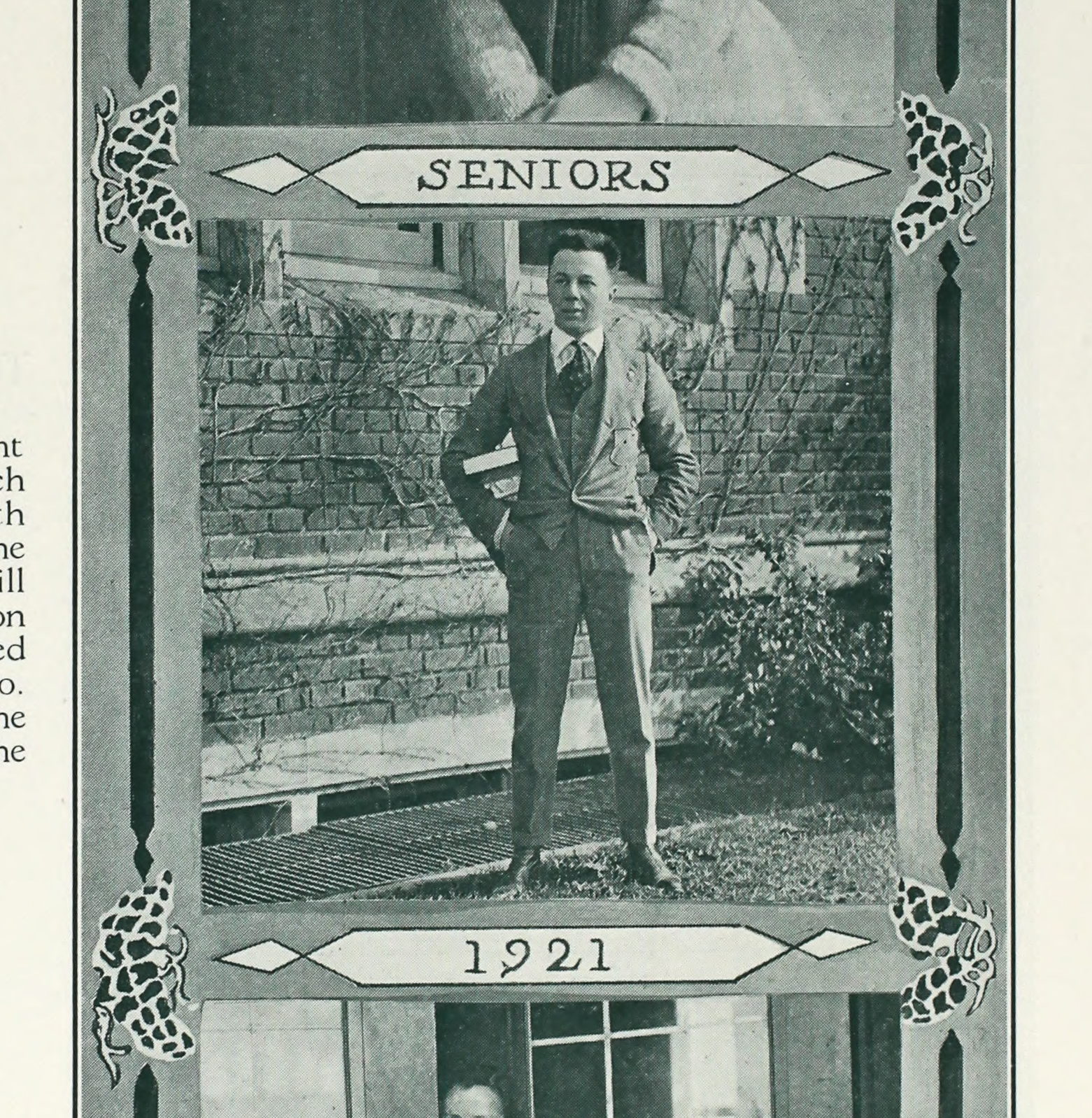

Born in Portland in 1896, Goodman grew up in Chehalis, Washington. One enduring mystery is his birth name. On a high school report card, his high school diploma, and the 1918 University of Washington student directory, he is Isey M. Goodman. But in the 1921 yearbook for Reed College, where he transferred in his junior year, he was Irvin Martin Goodman. On legal documents, such as draft records, he is "Irvin."

Goodman entered the pre-law program at Reed, majoring in sociology, and was part of the debate team. He also played the violin, which he played throughout his life despite a hearing impairment. After graduating from Reed in 1921, he enrolled at Northwestern College of Law (now Lewis & Clark Law School), clerking at the Meier & Frank department store to pay his tuition. While in law school, he argued two cases before the Multnomah County District Court and was associated with the law firm Manning and Harvey. He graduated from Northwestern in 1923.

While at Reed, Goodman had written that when he was growing up he observed police officers hitting prisoners and “decided [his] practice would involve only cases of social justice.” By 1932, he was known as the leading radical lawyer in Portland. As the local attorney for International Labor Defense (IDL), widely considered an arm of the Communist Party USA, he represented laborers and union organizers charged with, among other crimes, criminal syndicalism, a law used to target members of the Communist Party.

It was also in 1932 that Gus Solomon—who would become a U.S. District Court judge in 1950—accepted Goodman’s invitation to collaborate, which resulted in the informal partnership of Goodman, Levinson & Solomon. A rift between the Oregon branch of the ACLU and IDL emerged during the 1934 maritime strike, when the ACLU tried to convince unions to distance themselves from communist factions. By the late 1930s, Solomon had aligned himself with the ACLU, while Goodman had aligned himself with the IDL. The firm closed its doors in 1938 when Goodman ran for Multnomah County district attorney, a race he lost. Years later, Leo Levinson recalled that “we decided we must separate because the arguments were getting pretty tense sometimes in the office.” At about the same time, Goodman met Ora Kirshner, a librarian at the University of Oregon Medical School (now Oregon Health and Sciences University). They married in 1940.

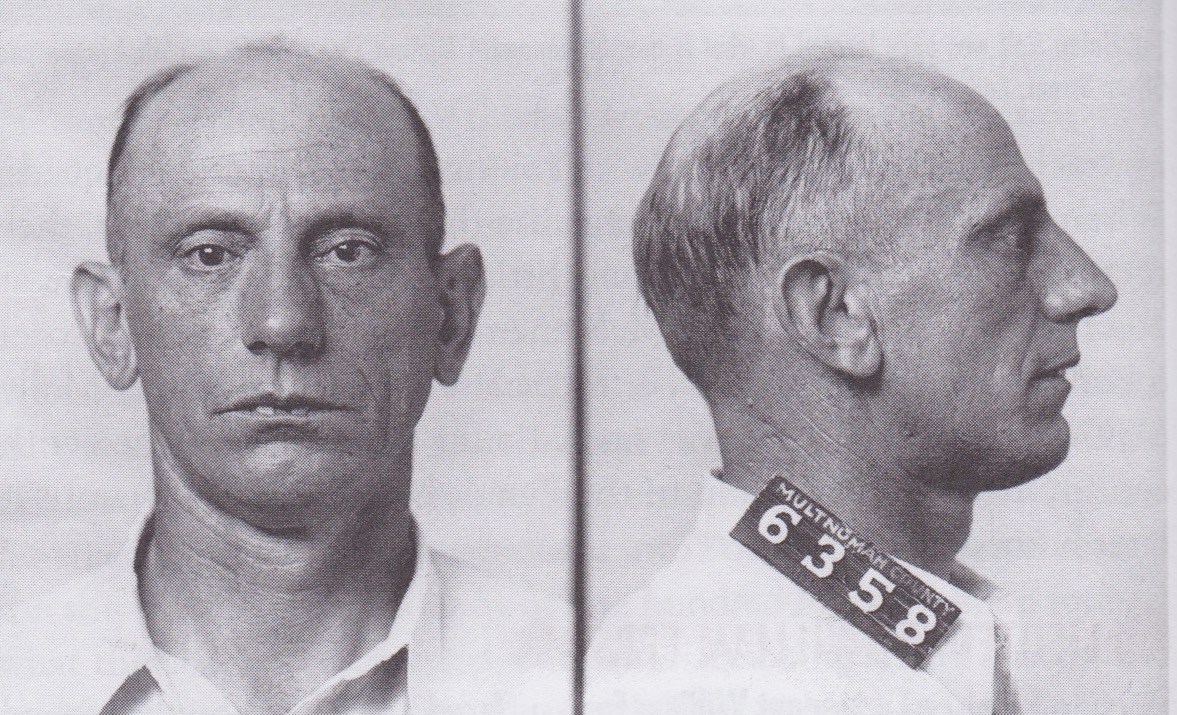

Goodman is best known for his representation of people charged with criminal syndicalism in the 1930s. Many of his clients were immigrant laborers who had joined the Communist Party with the hope of improving their pay and working conditions. Among them was Dirk De Jonge, a communist and World War I veteran who once ran for mayor of Portland. He was convicted of criminal syndicalism in 1935 and sentenced to ten years in prison. In 1937, the U.S. Supreme Court, in De Jonge v. Oregon, reversed his conviction on the grounds that the Oregon criminal syndicalism law violated the constitutional right to assemble. Several years later, at Goodman’s urging, the Oregon Legislative Assembly repealed the law.

Goodman represented Theodore Jordan, a Black railroad worker charged with murdering a white dining-car steward in what became known as the Oregon Scottsboro case. At trial in 1934, Goodman argued that Jordan’s confession had been coerced by a white Southern Pacific detective who had used an electrical device to burn him on the neck. Jordan was convicted and sentenced to death. The Oregon Supreme Court affirmed his conviction, which was set aside thirty years later on the grounds that the confession had been coerced. Goodman also defended a lieutenant in the Soviet Navy, Nicolai Gregorovich Redin, who was charged with being a spy. At the end of a three-week trial in 1946, a jury acquitted him of all charges.

Goodman’s last high-profile case was the murder trial of Sherry and Wei Him (Wayne) Fong, a mixed-race couple charged with murdering a sixteen-year-old Lincoln High School student who babysat for them the night before she disappeared on January 6, 1954. The case made headlines in Portland, with stories about heroin and prostitution, miscegenation and violence, the danger of Chinatown, and the good-looking young soldier who loved the girl. A jury found the Wongs guilty of first-degree murder and sentenced them to death, but the judge set aside the verdict, stating that the prosecution's case offered "no reputable showing of either malice or premeditation." When the state tried the Wongs separately a second time, the judge acquitted Wayne, but Sherry was convicted. After a successful appeal to the Oregon Supreme Court in 1958 and two more trials, however, Sherry was acquitted. Goodman did not represent Sherry Wong in her fourth trial, perhaps because of failing health.

Goodman died on June 30, 1958. “For more than 30 years,” his obituary in the Oregon Journal noted, “he had the reputation as ‘the lawyer who never gives up.’” Oregon Senator Richard Neuberger wrote to Ora Goodman: “Irvin Goodman was a man with a keen sense of social justice, great courage and resourcefulness in the courtroom and with profound compassion for the underdog in life.”

-

![]()

Irvin Goodman, Reed College yearbook, 1921..

Courtesy U.S., School Yearbooks, 1880-2012; Reed College; 1921

-

![]()

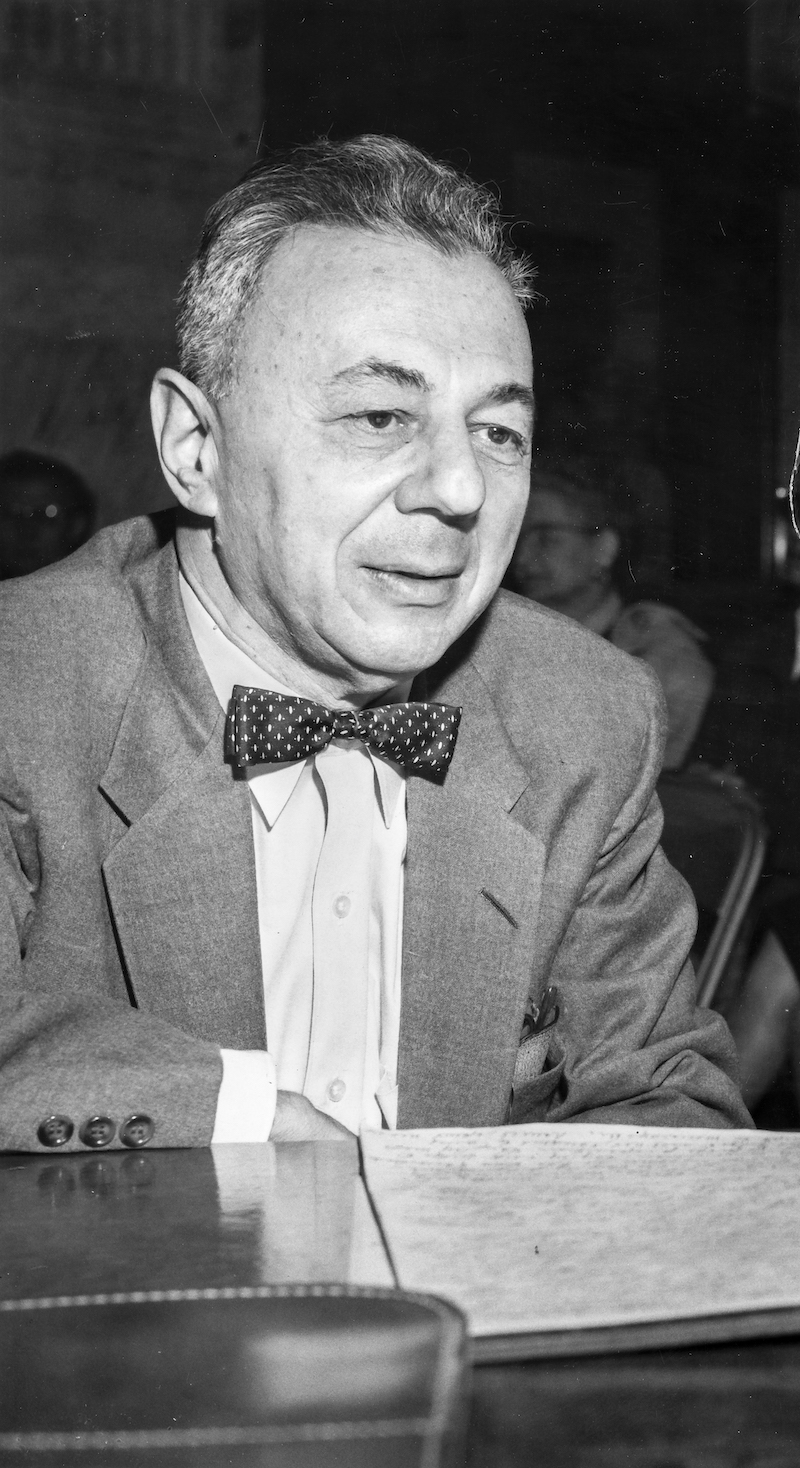

Irvin Goodman.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Library

Related Entries

-

![Criminal Syndicalism Law of Oregon]()

Criminal Syndicalism Law of Oregon

Oregonians were light-headed from days of celebrating the end of World …

-

![Gus J. Solomon (1906–1987)]()

Gus J. Solomon (1906–1987)

Gus J. Solomon, the longest-serving federal judge in Oregon history, wa…

-

![Socialism in Oregon]()

Socialism in Oregon

When Postmaster General James Farley jokingly toasted the " Soviet of W…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Irvin Goodman papers, Mss 1811, Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Portland.

Stein, Harry. Gus J. Solomon, Liberal Politics, Jews, and the Federal Courts. Portland: Oregon Historical Soc. Press, 2006.

Munk, Michael. The Portland Red Guide. Portland, Ore.: Ooligan Press, 2011.