The Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) administers and enforces environmental laws pertaining to the air, soil, and surface and ground water and serves as the Environmental Protection Agency’s delegate in ensuring compliance with federal laws such as the Clean Water Act and the Clean Air Act. Created in 1969, the DEQ is an autonomous agency that superseded the Oregon State Sanitary Authority (OSSA).

The Oregon legislature created the DEQ during Tom McCall’s second year as governor (1967-1975), one element of what some journalists called “the most extensive shake-up of state government” in Oregon history. For decades, the state had centralized its oversight of water and air quality and solid waste management. The Oregon State Sanitary Authority (1938) was responsible for water quality, and the Oregon Air Pollution Authority (1951) oversaw air quality; the Air Pollution Authority was made part of the OSSA in 1959. In 1967, McCall led efforts to strengthen the OSSA, and in early March 1969 his legislative allies, including Republican Senator Victor Atiyeh, proposed Senate Bill 396 to separate the Sanitary Authority from the State Board of Health and create a new agency. Overseeing the Department of Environmental Quality would be a five-member, governor-appointed citizen panel—the Environmental Quality Commission—which would establish policies and provide guidance for the agency’s day-to-day work. McCall agreed to the reorganization and signed the bill on June 16, 1969.

The late 1960s in the United States was a time of increased public attention on environmental issues and the need to strengthen environmental laws, and the creation of the DEQ put Oregon at the forefront in translating public sentiment into an effective regulatory and administrative framework. In early 1969, President Richard Nixon named McCall, conservationist Laurance Rockefeller, and aviator Charles Lindbergh to his Citizens Advisory Committee on Environmental Quality to provide input on what became the National Environmental Policy Act. In October 1969, David D. Dominick of the Federal Water Pollution Control Administration called Oregon’s water pollution program among the most progressive and effective in the nation. In effect, Oregon’s environmental laws provided examples for federal legislation such as the National Environmental Policy Act (1970) and the Clean Water Act (1972) and the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (1970).

The first director of the Oregon DEQ was State Sanitary Engineer Kenneth Spies, who replaced the chair of the now-defunct OSSA, John Mosser, in July 1969. In September 1971, the Environmental Quality Commission replaced Spies with L. B. Day, a former legislator and a regional coordinator for the U.S. Department of the Interior with responsibilities for monitoring environmental protection efforts for estuaries. McCall had handpicked Mosser to lead the OSSA in 1967 because he wanted the agency to take a more active approach in ensuring statewide air and water quality, and he chose Day to head the DEQ for the same reason.

Under McCall’s leadership, state officials made progress in pressuring industrial polluters to change their practices. In no small part this was because McCall significantly increased funding for the OSSA and the DEQ. The OSSA’s budget during the final two years of Governor Mark O. Hatfield’s tenure, 1965-1967, was $289,921; during McCall's first four years in office, the appropriation increased to $635,627 for 1967-1969 and $716,624 for 1969-1971.

With Day at the helm, the DEQ leveraged its funding and increased enforcement powers to force the Boise Cascade company’s compliance with state water quality laws at its Salem pulp and paper mill, which had a long history of noncompliance and resistance to installing abatement systems. In the face of Boise Cascade’s intransigence, in July 1972 the DEQ requested a Marion County Circuit Court order to enforce waste discharge permit stipulations and shut down the mill. The company, of its own volition, closed the mill to install the necessary equipment, but Day nevertheless proceeded with the DEQ’s suit. Echoing McCall, he told Oregonians that “there is no reason why we can’t have jobs without pollution.” Millworkers and their supporters were outraged, but the DEQ succeeded in creating meaningful change at the Salem mill.

The DEQ’s responsibilities evolved with changes to federal and state laws, which tended to require stricter pollution control limits, address public health, and protect ecosystems. Notable examples include:

Air: Leading the nation in the implementation of the first air contaminant discharge permit requirements (1972); initiating vehicle emissions inspections (1975); implementing strengthened federal air permitting program under 1977 Clean Air Act amendments; establishing a national standard for industrial air permitting (1990); enforcing the legislature’s 2009 ban on most open-field burning in the Willamette Valley.

Water: Administering the federal 1972 Clean Water Act and subsequent revisions, which set standards for surface waters and ground water; strengthening storm water runoff policies (1995).

Land and Solid Waste: Requiring solid waste permits (beginning in 1971); establishing standards for reclaiming brownfield sites for redevelopment (1994); initiating or expanding recycling programs for glass bottles (2007), electronics (2009), and paint (2010), the last of which was the nation’s first.

The DEQ works closely with many other organizations. In 2000, for example, the agency joined with the federal government to designate the Portland Harbor Superfund Site on the Willamette River, collaborating with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the City of Portland, tribal governments, community groups, and private companies to mitigate over a century of unregulated industrial activities. DEQ is tracking nearly 170 individual properties within the Superfund Site, and cleanup costs could be as high as $2 billion.

The Oregon DEQ operates from its headquarters and a laboratory in Portland and three regional offices: Northwest (Tillamook), West (Coos Bay, Eugene, Medford, and Salem), and East (Bend, Klamath Falls, La Grande, Pendleton, and The Dalles). The agency’s seven hundred staff members provide inspection, monitoring, analysis, permitting, licensing, and technical services, as well as emergency spill response and cleanup.

-

![]()

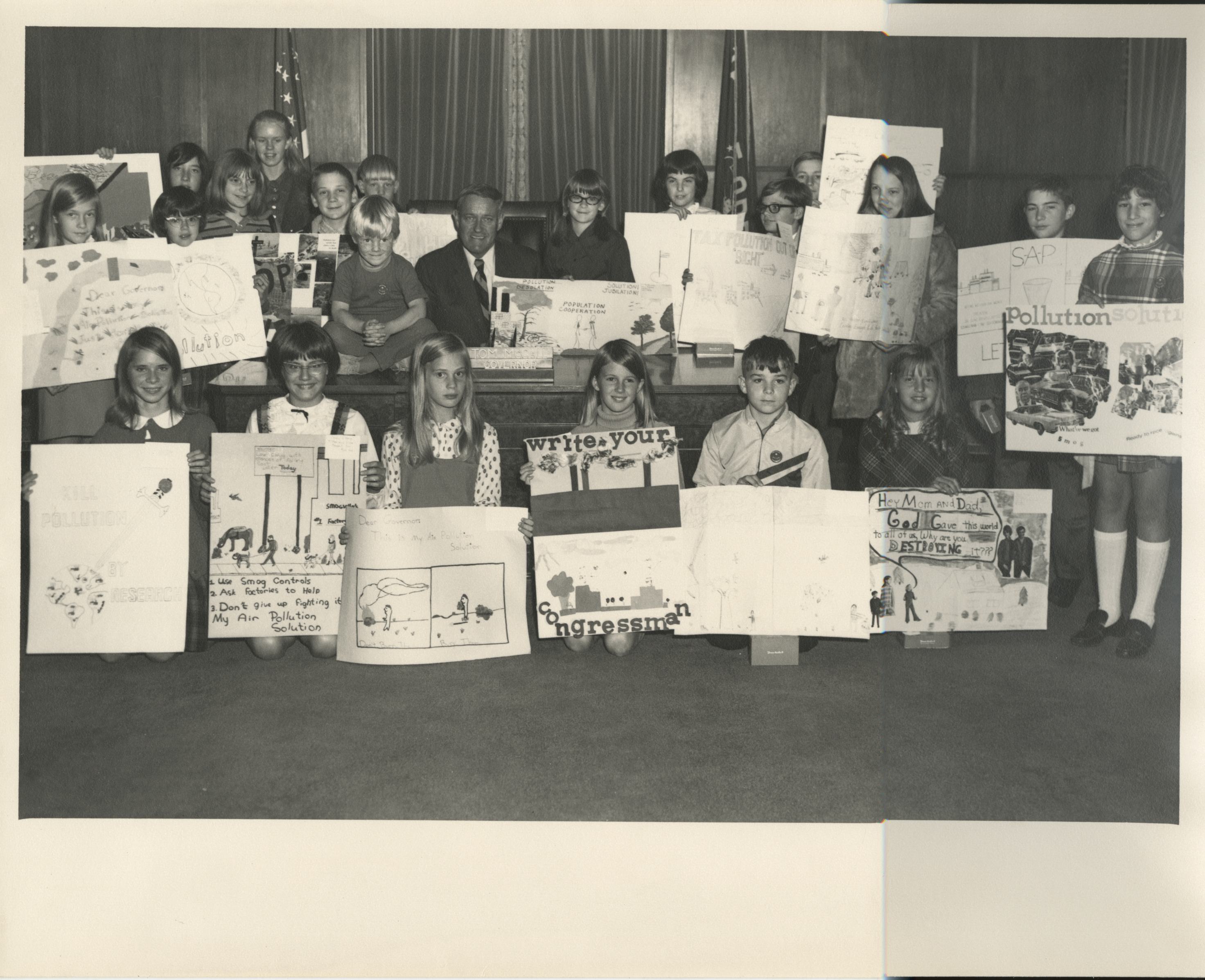

Willamette Valley Clean Air poster contest, 1969.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi105878

-

![]()

Clean Air Week, 1969.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi103775

-

![]()

Sanitarian Bob Jackson inspecting Milton Creek for pollution, 1970.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 020607

-

![]()

Willamette River sewage flow (arrow), 1938.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 014541

-

![]()

Boys fish over the Crown Mill sewer outflow, 1960.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 018142

-

![]()

Portland air pollution, 1963.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 022557

-

![]()

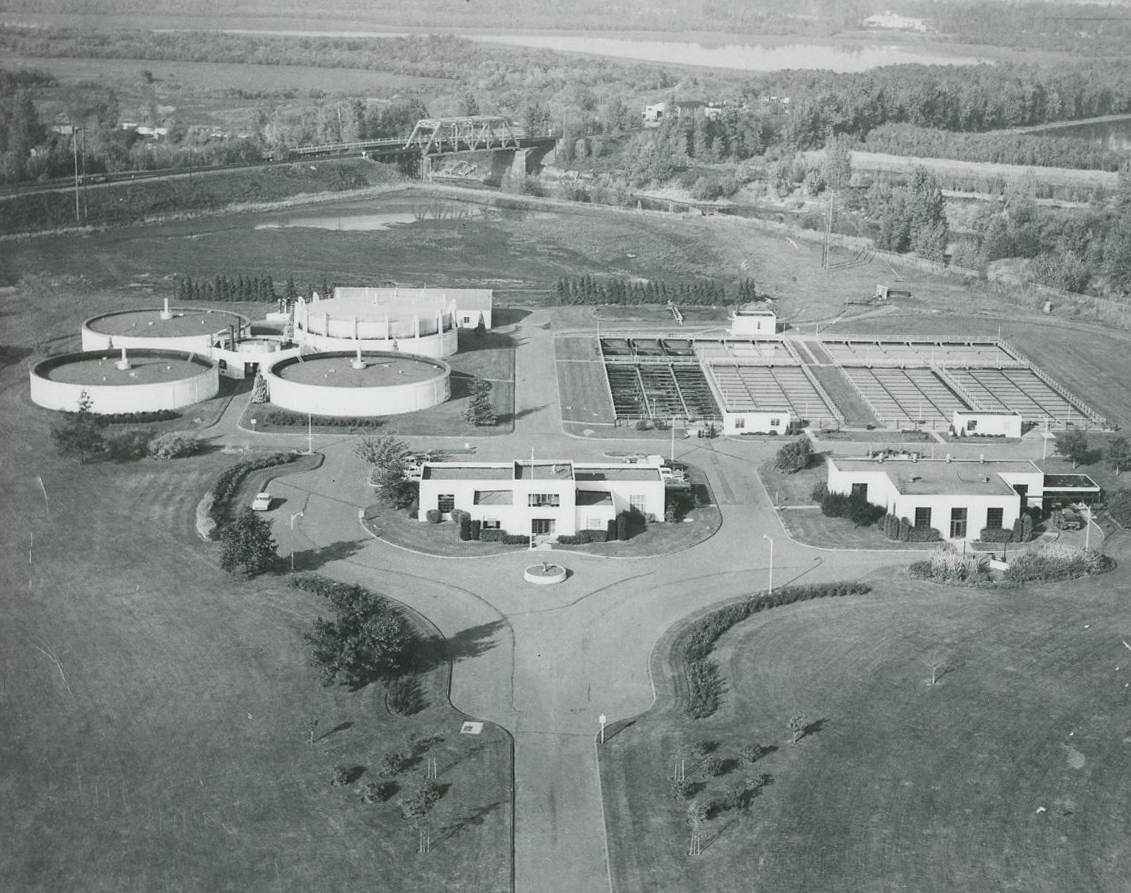

Portland's main sewage treatment plant, 1966.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 018 59

Related Entries

-

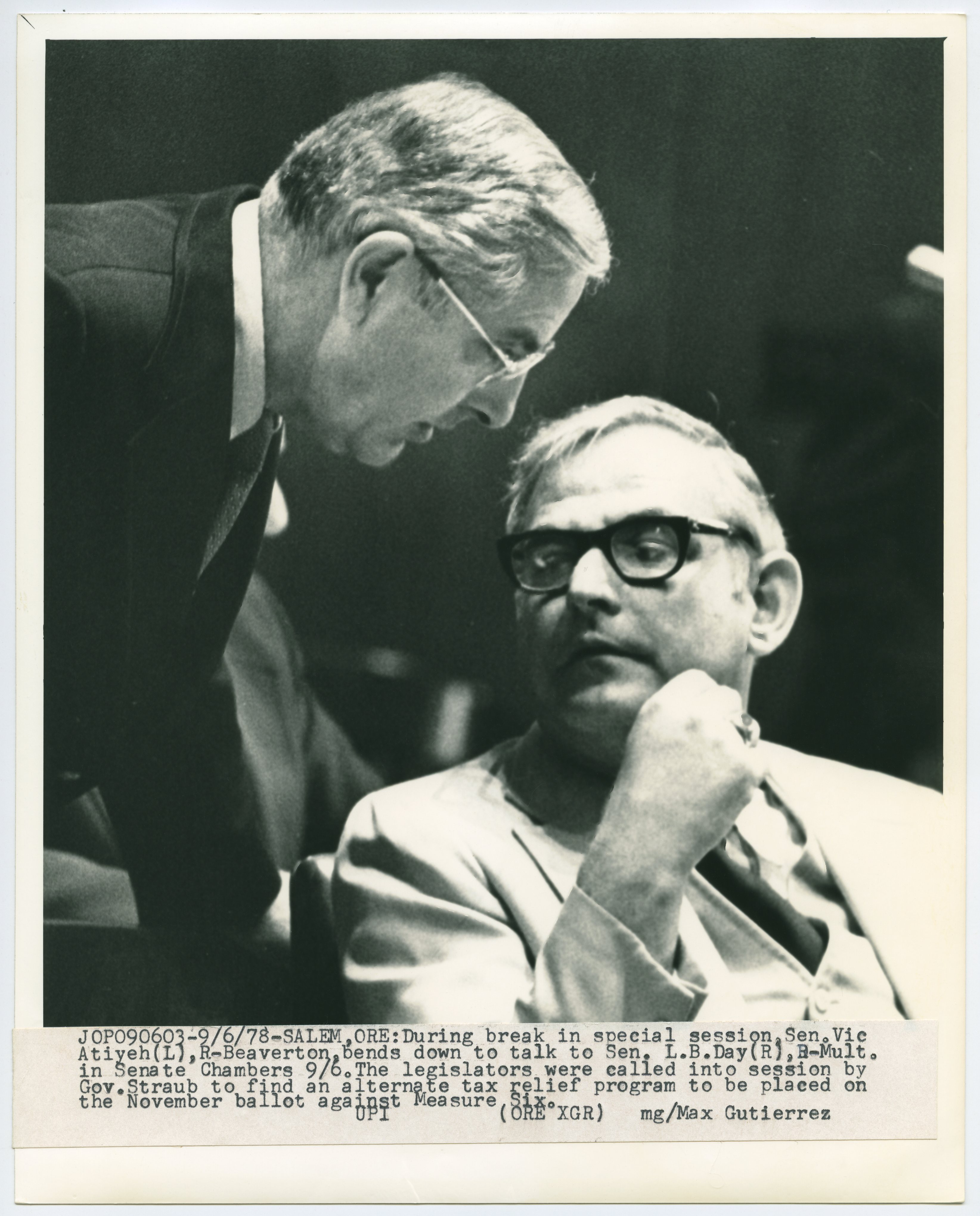

![L. B. Day (1932-1986)]()

L. B. Day (1932-1986)

L.B. Day was one of a handful of political giants who played leadership…

-

![Pollution in Paradise (documentary film)]()

Pollution in Paradise (documentary film)

KGW-TV aired Tom McCall’s one-hour documentary Pollution in Paradise on…

-

![Thomas William Lawson McCall (1913-1983)]()

Thomas William Lawson McCall (1913-1983)

Tom McCall, more than any leader of his era, shaped the identity of mod…

-

Willamette River

The Willamette River and its extensive drainage basin lie in the greate…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

“Fact Sheet: DEQ Snapshot,” Oregon Department of Environmental Quality, June 14, 2012, available at www.deq.state.or.us/pubs/general/Snapshot12-OD-001.pdf, accessed Feb. 6, 2016.

“Oregon Department of Environmental Quality, Administrative Overview,” Salem: State of Oregon Office of the Secretary of State, Nov. 2009. https://sos.oregon.gov/

OSSA Minutes Nov. 24, 1959, vol. 3, pp. 311-312.

Rogers, Samuel M. “Air Pollution Legislation—A Review of Current Developments.” American Journal of Public Health 50:5 (May 1960): 642-648.

Kenworthy, E.W. “Tough Rules Saving a Dying Oregon River.” New York Times, Sep. 8, 1970, p. 50.

Oregon Department of Environmental Quality, “About the Environmental Quality Commission,” http://www.deq.state.or.us/about/eqc/eqc.htm, accessed Jan. 28, 2012.

“McCall Signs Last of Bills.” Oregonian, June 17, 1969, sec. 1, p. 13.

Rockefeller, Laurence S. Chair. “Report to The President and The Council on Environmental Quality.” Washington, D.C.: Citizens' Advisory Committee on Environmental Quality, April 1971

Walth, Brent. Fire at Eden’s Gate: Tom McCall & the Oregon Story. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 1994.

Olmos, Robert. “Willamette River Now Said Reasonably Safe for Portland Area Water Sport Enthusiasts.” Oregonian, July 7, 1969, sec. 1, p. 27.

“Pollution Gains Made.” Oregonian, July 26, 1969, sec. 1, p. 12.

“Court Order Sought to Prevent Pollution.” Oregonian, July 25, 1972, sec. 1, p. 23

Kadera, Jim. “Boise Cascade Shuts Salem Plant.” Oregonian, July 26, 1972, sec. 1, p. 1.

Johnson, Keith. “DEQ Portland Harbor Upland Source Control Status,” Oregon Department of Environmental Quality, Nov. 24, 2014. www.deq.state.or.us/lq/cu/nwr/PortlandHarbor/docs/SCupdateNov2014.pdf