The mission of the U.S. Life-Saving Service was to rescue those in peril from the sea. To serve that mission, the federal government built coastal stations to house the men and equipment engaged in rescue operations. The stations were integral in the development of Oregon's coastal communities, whose livelihood and connection to other places depended on safe water travel.

Established in 1871, the USLSS had its roots in the Massachusetts Humane Society founded in 1785. Maritime trade was key to the survival of the young nation. With shipwrecks came not only loss of life but also monetary loss, and that needed to be staunched.

Oregon's first life-saving station, staffed by a keeper on an island, was erected at Cape Arago in 1878. When a rescue was needed, the keeper, who had no view of the coastline, had to be informed of the emergency. He then would row to town to look for volunteers. Years went by without a single rescue. This first step led to fully staffed stations at Point Adams near Astoria in 1889, Coquille River at Bandon in 1890, Umpqua River near Winchester Bay in 1890, Yaquina Bay at South Beach in 1896, and Tillamook Bay at Barview in 1908. With more stations, men, and funding, the success and reputation of the lifesavers grew.

Typically, a crew was made up of eight surfmen and a keeper. The number of men was determined by how many were needed to row a lifeboat; motor lifeboats were not available until about 1910. Life-saving stations had to be near a place where boats could be launched during a storm. In addition to a station house and a boathouse, crewmembers often built homes next door on government land to house their families.

The USLSS schedule was military in its precision. Mondays and Thursdays were spent practicing with the beach apparatus, which involved firing a cannon with a projectile that carried a line over a simulated wreck mast. The crew then erected a breeches buoy in which people could be rescued from ship to shore. Tuesdays were reserved for boat drills, which involved launching, capsizing, rowing, and landing. Wednesdays were signal flag practice. Fridays were dedicated to medical training. Saturdays were station and equipment maintenance days. On a rotating basis, crewmembers each got one day off a week.

Only twenty life-saving stations operated on the Pacific Coast, compared to hundreds for the Atlantic Coast. Ports are at a distance from each other in the West, so ships tended to go farther out and then cut in at harbors. Still, the mouth of the Columbia River is named the Graveyard of the Pacific for a reason, as more than 230 major shipwrecks have occurred in or around the Columbia Bar.

Two major Oregon Coast shipwrecks held the attention of the nation during the time of the USLSS—one famous, the other infamous. The Rosecrans ran aground on Peacock Spit at the mouth of the Columbia on January 7, 1913. Through heroic actions by the crews of the Point Adams station and its sister station at Cape Disappointment, two people were rescued. The day-long endeavor, during which two motor lifeboats were sunk, became the stuff of legend among surfmen. Sixteen gold life-saving medals were awarded, a record number that has not been broken since.

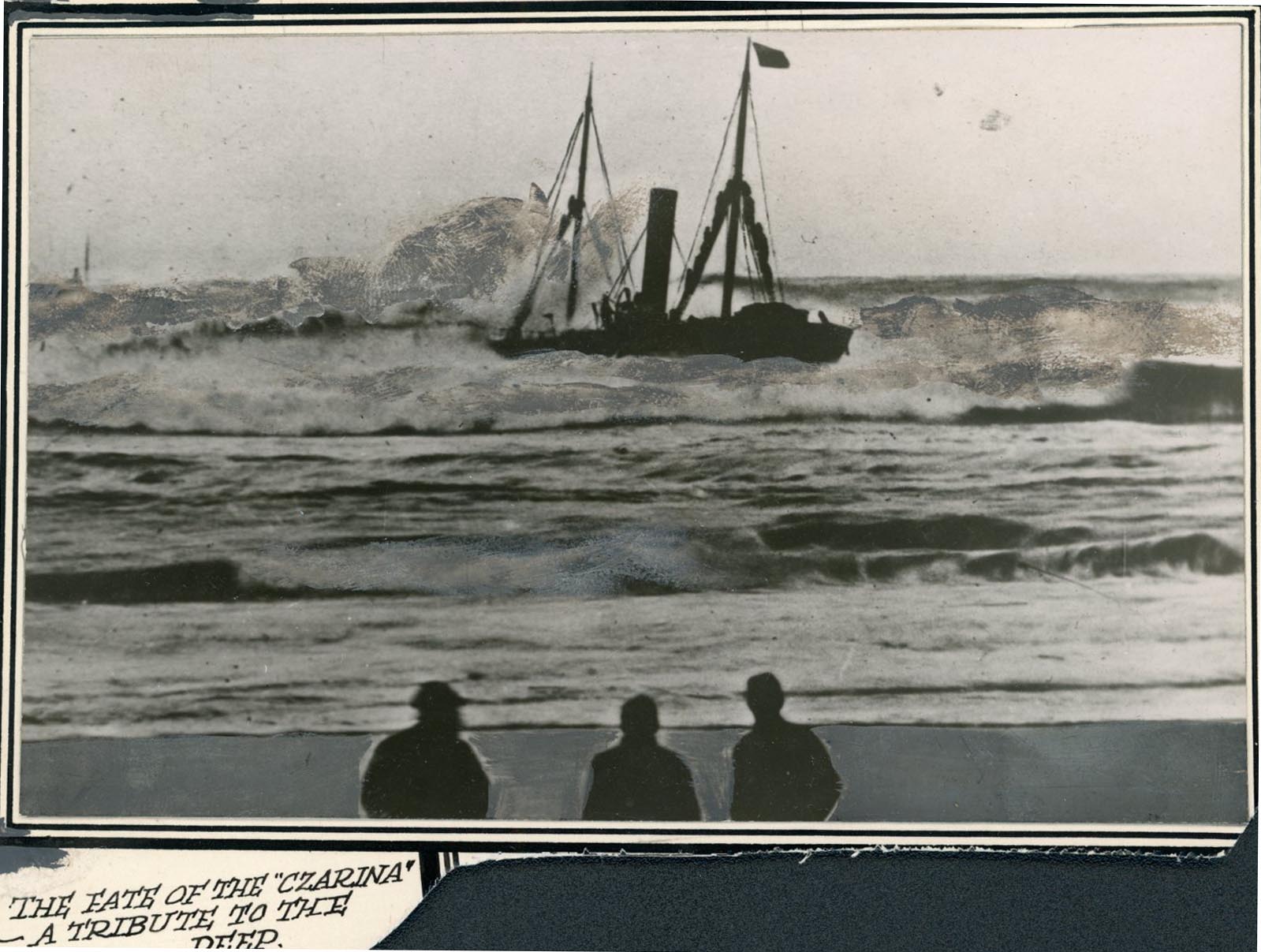

The USLSS Annual Report called the wreck of the Czarina, on January 12, 1910, the most "appalling marine casualty" in a quarter century. All but one of the crew died, and newspapers vilified the keeper and crew for not doing more. The lifesavers credo has always been, "You have to go out, but you don't have to come back," and the public felt the rescue attempts had not been enough. After a lengthy investigation, the station keeper was charged with dereliction of duty and forced to resign.

Few visible signs of the USLSS are left in Oregon. A complete station still exists at Barview, Point Adams has its original boathouse, and Yaquina Bay still has the lighthouse where lifesavers were stationed from 1906 to 1933. After it merged with the Revenue Cutter Service in 1915 to become the U.S. Coast Guard, the life-saving stations became more substantial to support larger crews. In 1939, the U.S. Lighthouse Service also became part of the Coast Guard. With the merger of these three government services, the Coast Guard became the primary protector of mariners.

-

![USLSS surfboat crew, Barview Station, 1908.]()

USLSS Sta Barview, surfboat, 1908.

USLSS surfboat crew, Barview Station, 1908. Courtesy David Pinyerd

-

![USLSS Station Cape Arago, 1885.]()

USLSS Sta Cape Arago, 1885.

USLSS Station Cape Arago, 1885. Courtesy USCG HQ Life Saving Svc. Photos: Personnel file -

![USLSS Station, Barview, about 1910.]()

USLSS Sta Barview, ca 1910.

USLSS Station, Barview, about 1910. Courtesy David Pinyerd

-

![USLSS Station Umpqua, about 1910.]()

USLSS Sta Umpqua, boatroom, ca 1910.

USLSS Station Umpqua, about 1910. Courtesy USCG HQ -

![USLSS Station Point Adams, about 1910.]()

USLSS Sta Point Adams, ca 1910.

USLSS Station Point Adams, about 1910. Courtesy USCG HQ -

![USLSS Station Coquille, 1916.]()

USLSS Sta Coquille, 1916.

USLSS Station Coquille, 1916. Courtesy USCG HQ Coquille River file -

![USLSS Station Yaquina, 1917.]()

USLSS Sta Yaquina lighthouse, 1917.

USLSS Station Yaquina, 1917. Courtesy USCG HQ Yaquina Bay file -

![USLSS Station Umpqua, 1923.]()

USLSS Sta Umpqua, 1923.

USLSS Station Umpqua, 1923. Courtesy USCG HQ Umpqua River file

Related Entries

-

![Columbia River]()

Columbia River

The River For more than ten millennia, the Columbia River has been the…

-

![Czarina]()

Czarina

The wreck of the Czarina is remembered as a tragedy that had no heroes,…

-

![Point Adams Lighthouse and Life-Saving Station]()

Point Adams Lighthouse and Life-Saving Station

Point Adams was given its name by Captain Robert Gray, who in his offic…

-

![Shipwrecks in Oregon]()

Shipwrecks in Oregon

Approximately three thousand ships have met their fate in Oregon waters…

-

![The Beach Patrol in Oregon, U.S. Coast Guard, 1942-1944]()

The Beach Patrol in Oregon, U.S. Coast Guard, 1942-1944

The Beach Patrol in Oregon, which kept watch over the Oregon coastline …

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Pinyerd, David. Lighthouses and Life-Saving on the Oregon Coast. Charleston, N.C.: Arcadia Press, 2007.

Shanks, Ralph and Wick York. The U.S. Life-Saving Service: Heroes, Rescues and Architecture of the Early Coast Guard. Petaluma, CA.: Costaño Books, 1996.