Oregon’s Treasure Trove Act (ORS 273.718-273.742), which lasted from 1967 to 1999, regulated persistent treasure-hunting activity on state lands, especially in the Neahkahnie Mountain area in Tillamook County. Conflict between treasure-seeking and archaeological protection eventually led to a moratorium on treasure-hunting on state properties and finally to a repeal of the statute.

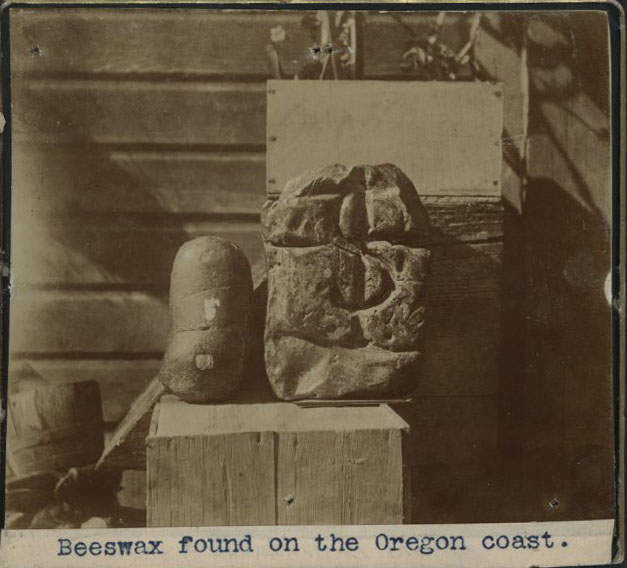

Neahkahnie Mountain and its environs have been a favored treasure-hunting site since the early nineteenth century for several reasons. First, the late-seventeenth-century wreck of a ship on nearby Nehalem Spit, now believed to be the Spanish Manila galleon Santo Cristo de Burgos, left a trail of Chinese porcelain fragments, beeswax chunks, and large ship timbers and fueled speculations of treasure among EuroAmerican settlers. Second, early accounts of the wreck, principally narrated by Native people, changed the story’s focus to treasure-hunting, partly because early boosters, such as the owners of Seaside House in the resort town of Seaside, encouraged Native storytellers they employed to enhance the oral tradition for the benefit of guests. In addition, early news accounts in regional newspapers, such as the Wheeler Reporter, focused on the possibility of treasure in the area from one or more shipwrecks. Finally, fictionalized accounts by writers, including McMinnville’s Thomas Rogers, mixed authentic traditions with fantastical tales of Spanish treasure, pirates, buccaneering, romance, and exploits on the high seas.

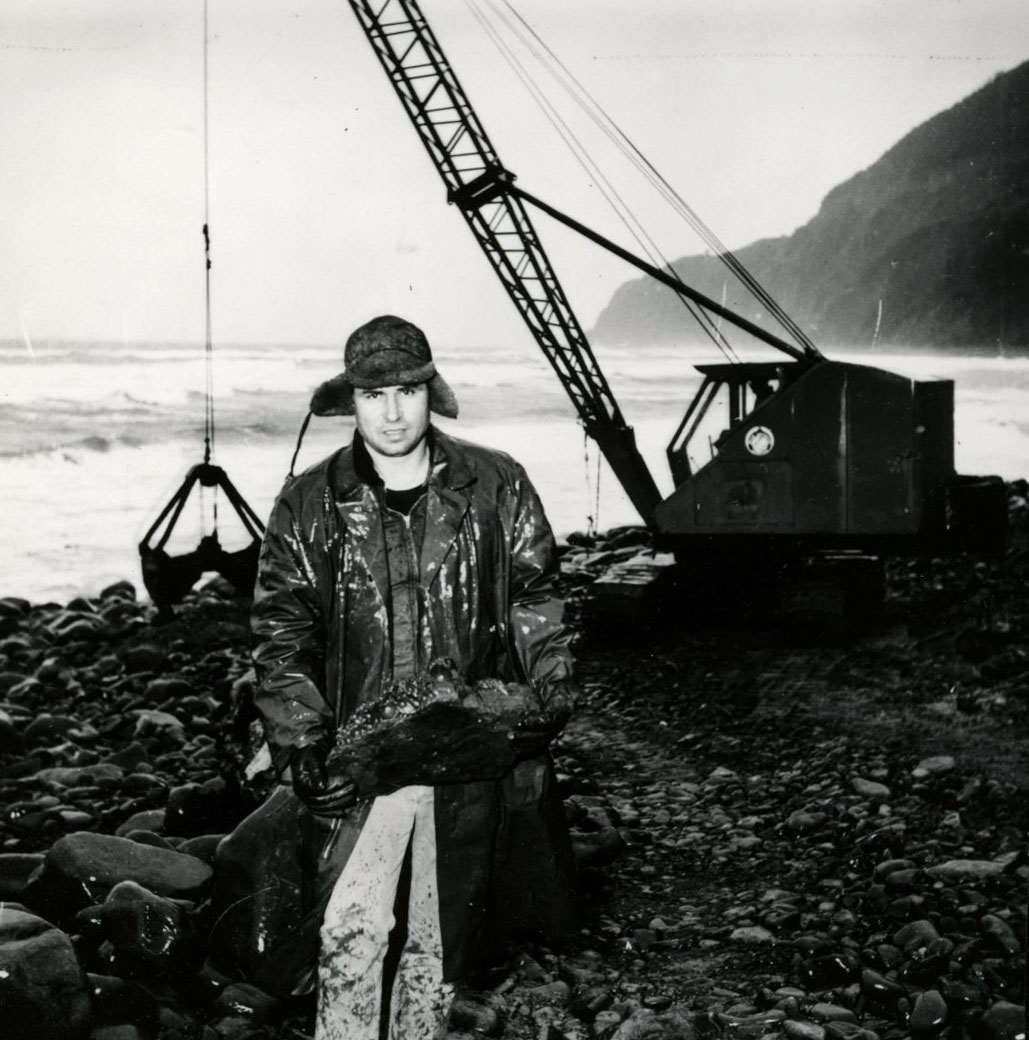

By the turn of the twentieth century, Neahkahnie Mountain was Oregon’s principal treasure-hunting venue, and it was the persistent treasure-seeking activity of Salem housepainter Edward M. Fire, also known as Tony Mareno, that led to passage of the Treasure Trove Act. In 1966, Fire sought an archaeological permit through the University of Oregon to dig for treasure in Oswald West State Park, which encompasses the westward slopes of Neahkahnie and the beaches. When he was denied a permit, he got in touch with his state representative, John W. Anunsen, who sponsored the law.

Passed in 1967, the Treasure Trove statute allowed people to dig for treasure on state land if they had a permit, although it did not define what a “treasure trove” was, and divided the value of treasure found between the finder, who received 75 percent, and the Common School Fund. The statute allowed state officials some oversight over treasure-seekers’ activities on state lands, but the agencies had little statutory authority to require bonds for cleanup and had insufficient personnel to monitor treasure-hunters.

Amendments to the statute in 1973 defined “treasure trove” as “money, coin, gold, silver, precious jewels, plate and bullion found hidden in the earth or other private place where the true owner thereof is unknown.” Authority for treasure-seeking was shifted from the Parks Division to the Division of State Lands, and 75 percent of the benefits from treasure found was assigned to the Common School Fund, with 25 percent given to the finder. The amended law also recognized that if the treasure had historic value, then it must be placed in a museum, with the finder compensated by the Common School Fund in an amount equal in value to the find.

It became clear by the early 1980s that cultural resources protection laws and the Treasure Trove law frequently laid claim to the same objects, and that the state might be liable for a great deal of money to compensate seekers who found valuable treasure. The conflict was laid out with special clarity in an Attorney General’s Opinion of April 18, 1983, concerning a seeker who claimed he might have found the Ark of the Covenant on Neahkahnie Mountain. The attorney general pointed out that such a priceless object would be considered both treasure trove and an archaeological artifact under existing law.

By the early 1980s, the Division of State Lands had begun issuing only treasure-trove permits for nonintrusive exploration, eliminating searches by digging, bulldozing, drilling, trenching, and similar methods. With a concern over the integrity of archaeological sites on one hand and treasure-seekers hoping for a larger share of the treasure on the other (amendments in 1987 had given seekers 100 percent of the first $5,000 found), the Division of State Lands placed a moratorium on treasure-seeking on state lands in late 1989; the Parks Division followed suit. In 1991, the Land Board extended the moratorium indefinitely, in part because the initial moratorium had created a surge of renewed interest in treasure hunting and the state had received thirteen new applications for searches on Neahkahnie Mountain.

Once the moratorium was in place, Oregon formed a work group to investigate ways of reducing the conflict between treasure-seeking and archaeological protection, but the parties could not reach agreement. The statute was unworkable because of new permitting requirements, especially for sensitive sites like state parks and shipwrecks; confusion over archaeological protection requirements; problems of how to value found items; and the lack of penalty for violating a permit. Oregon’s tribes actively favored repeal.

The legislature repealed the Treasure Trove Act in 1999, but in many ways the practical consequences of repeal were negligible. No one had found any treasure during the law’s tenure, and there had been no activity for a decade because of the moratorium. Even before the moratorium, the agencies had required treasure-seekers to post a bond, repair damage to the land, and hire an archaeologist, costs that few applicants could afford.

The repeal did not affect the Native American Grave Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990, which only applies to human remains and funerary objects on federal or tribal land, but it did end the potential for head-to-head conflict between archaeological protection of artifacts and treasure-hunting. The Treasure Trove Act was doomed by rising concern for the protection of public lands and an increasing recognition of the importance of archaeological protection of historic sites.

-

![]()

Tony Mareno holds soapstone from shaft he dug at Neahkahnie, 1967.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., 013282

-

![]()

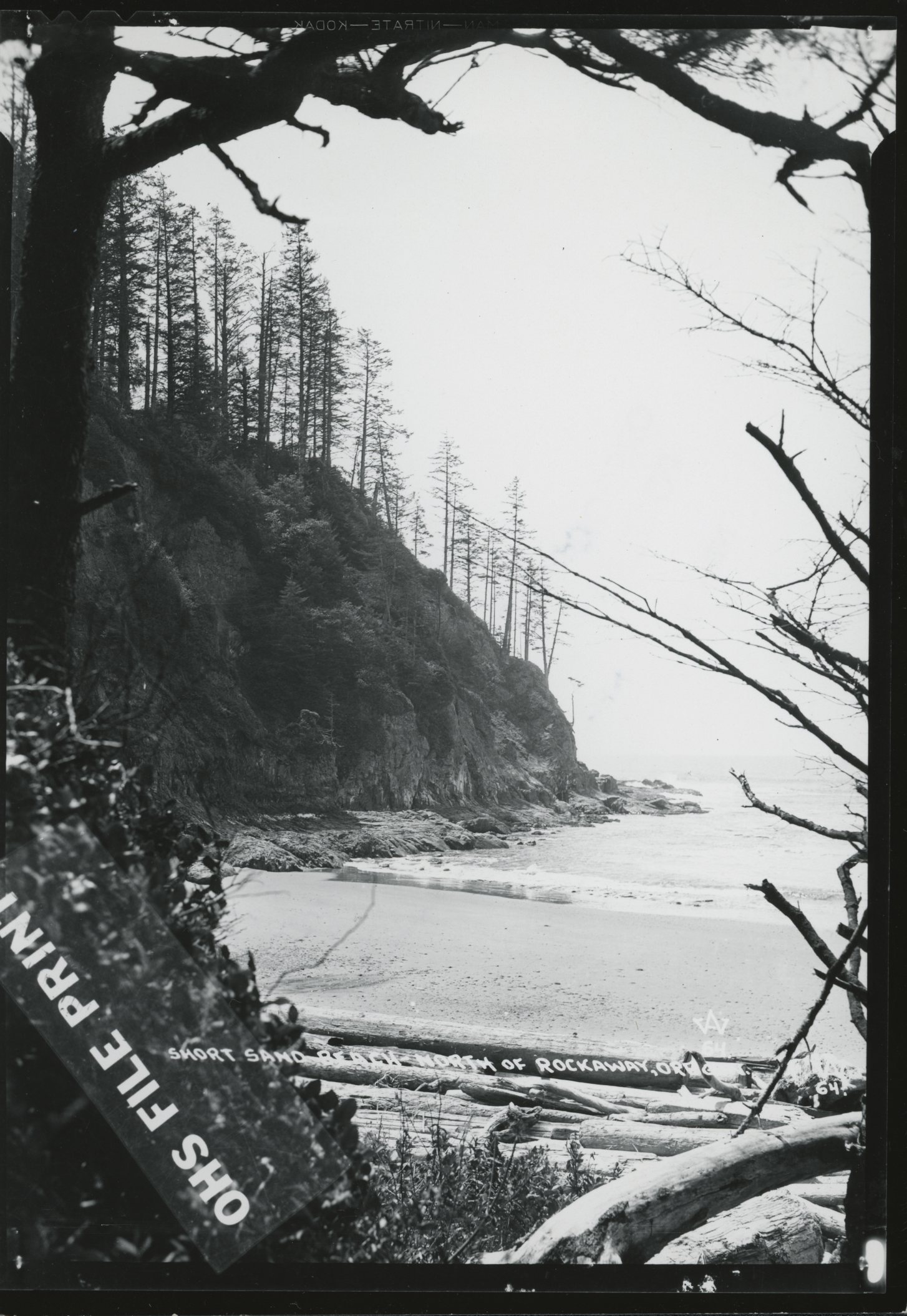

Neahkahnie Mountain, Oswald State Park, Oregon.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org. ba013289

-

![]()

Neahkahnie Mountain and rocky beach, c.1907.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Gi385

-

![]()

Beeswax found on the Oregon coast.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi92910

Related Entries

-

![Beeswax shipwreck]()

Beeswax shipwreck

Since the earliest days of EuroAmerican settlement on the Oregon Coast,…

-

![Neahkahnie Mountain]()

Neahkahnie Mountain

Neahkahnie Mountain, about twenty miles south of Seaside, is a prominen…

-

![Oswald West State Park]()

Oswald West State Park

Shortly after Samuel Boardman became Oregon’s first director of state p…

-

![Santo Cristo de Burgos]()

Santo Cristo de Burgos

The Manila Galleon Trade and the Wreck on the Oregon Coast Nehalem-Til…

-

![Shipwrecks in Oregon]()

Shipwrecks in Oregon

Approximately three thousand ships have met their fate in Oregon waters…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Griffin, Dennis. “There’s Gold on Them Thar Beaches or Searching for Treasure in All the Wrong Places: Oregon’s Attempt to Address the Public’s Lure of Shipwrecks and Treasure Trove.” Paper delivered at the 62nd Annual Northwest Anthropological Conference, Association of Oregon Archaeologists Symposium, Newport, 2009, copy available at the Oregon State Historic Preservation Office, Salem, Oregon.

Griffin, Dennis. “The Evolution of Oregon’s Cultural Resource Laws and Regulations.” Journal of Northwest Anthropology 43:1 (Spring 2009).

Griffin, Dennis. “A History of Underwater Archaeological Research in Oregon.” Journal of Northwest Anthropology 47:1 (Spring 2013).

La Follette, Cameron, Dennis Griffin, and Douglas Deur. “The Mountain of a Thousand Holes: Shipwreck Traditions and Treasure Hunting on Oregon’s North Coast.” Oregon Historical Quarterly vol. 119 (2) Summer 2018.