Molala Kate Chantal (also known as Molala Kate)—the daughter of Molalla Chief Yelkus (Kil-ke), a signer of treaties with the United States in 1851 and 1855—was born in Dickey Prairie, near present-day Molalla, Oregon, in about 1844. One of the last speakers of the Molalla language, Chantal was a principal informant to anthropologists and linguists studying Pacific Northwest Native languages and culture in the early twentieth century. She was known for her basket making and for teaching young people the art of weaving and beadwork. Images of Molala Kate appear in many books about the Indians of western Oregon.

A witness to the first non-Native settlements in the lower Willamette Valley, Molala Kate was a child when the northern Molalla (sometimes Molala, Molale, or Molele) people were removed to the Grand Ronde Reservation in 1856. The removal, ordered by Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer, was hurried to defray possible settler attacks on Native people during an aggressive anti-Indian campaign following the massacre at the Cascade Rapids.

The massacre began on March 12, 1856, as an attack on the American settlement at the Cascade Rapids by Yakama Chief Kamiakin and some Klickitat allies. Several people died, and subsequently the U.S. regular army under Phil Sheridan defeated the coalition and forced their retreat north, into Canada. Several Cascades tribal leaders were held accountable for the massacre, and most were hanged. In the wake of the massacre, Americans feared that all of the tribes in the region would rise up and attack American settlements in the Willamette Valley. An attack never occurred.

Following the massacre, several Native people were killed along the Columbia River, and Palmer acted quickly to save the Molalla people in Dickey Prairie. While negotiating the Willamette Valley Treaty, he aggressively reiterated his promises of food and housing made on January 22, 1855. Finally, in April 1856, after several days of negotiation, Molalla chiefs agreed to remove to the Grand Ronde Reservation. The Molalla had an encampment at the base of the Fort Yamhill camp on the 1856 reservation map. After five years at Grand Ronde and dissatisfied that Palmer’s promises had not been kept, the Molalla returned to Dickey Prairie.

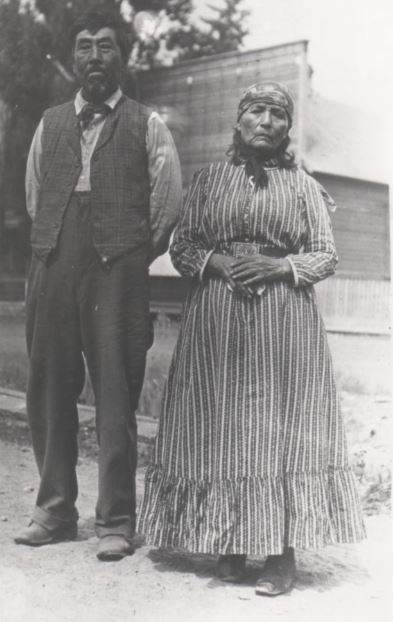

Molala Kate lived much of her early life at Dickey Prairie near her brother Chief Henry Yelkus (Yelkas, Yelkis), at the presumed location of the original Molalla village in the foothill river valleys of the Cascades. The daughter of a chief and strong-willed about her relationships, she was married for a short time to an unknown Molalla man, and then married to Renaldo Matches in 1868. Some Native people chose to live with suitable partners and were assumed to be married if they lived together for a significant time and underwent a Native ceremony. It is unknown whether Molala Kate’s marriages were arranged, even though that was common practice. She bore a son, Mathias John Williams, at The Dalles, where she was living among the Wasco, her father’s people. It was common in this time for women to marry and live with white men, who often left their Indian partners in order to pursue economic opportunities, such as the Gold Rush.

In 1880, census records record that Molala Kate married Irishman James Smith in Salem, where her son John and daughter Lizzie attended Chemawa Indian School. Federal records show that both of her children went to live on the Siletz Reservation, where John married Calusa Davenport and Lizzie married Hoxie Simmons. She then went to live in the city of Lincoln, on the Siletz Reservation. In 1894, she married Grand Ronde tribal member Louis Chantal, an Umpqua, at St. Michael’s Church on the Grand Ronde Reservation. She lived on Chantal’s allotment at Logsden for the remainder of her life. In her nineties, she cooked, tanned hides, and spent hours with her grandchildren telling them stories.

Linguist Leo J. Frachtenberg interviewed Molala Kate in 1910–1911 and collected Molalla stories. In 1927–1930, anthropologist Melville Jacobs worked with her, collecting Molalla stories that have never been fully translated. A few years later, in 1934, anthropologist Philip Drucker interviewed her and recorded Molalla ethnographies about canoes, camas digging, and other traditions. Despite the work done on Molalla languages, there is little about the tribe in the ethnographic records, likely because of the scarcity of Molalla tribal members on western Oregon reservation.

Molala Kate died on September 17, 1938. Her great niece and namesake, Kathryn Harrison, served on the early restoration councils of Siletz and Grand Ronde Reservations and was the first woman to serve as chair of the Grand Ronde people. Photographs of Molala Kate are among the few images of western Oregon Native women in full regalia. At times, the photographs have been exploited and described as being images of a cross-dressing Indian shaman, but those statements are incorrect.

-

![]()

Molalla Kate Chantal in traditional dress (crop).

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, OrHI65285

-

![]()

Molalla Kate Chantal in traditional dress..

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi65285

-

![]()

Henry Yelkis and Molalla Kate.

Unknown

Related Entries

-

![Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde]()

Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon is a confede…

-

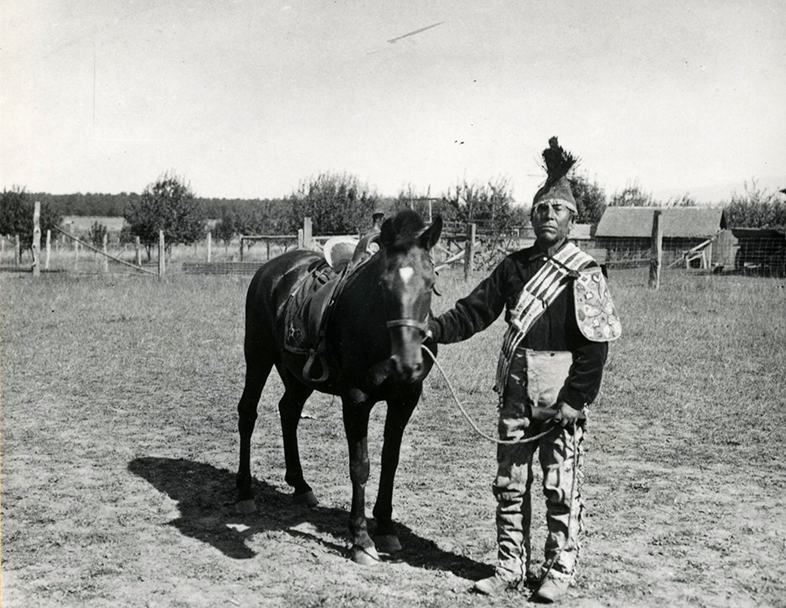

![Henry Yelkus (c. 1843–1913)]()

Henry Yelkus (c. 1843–1913)

Henry Yelkus (also spelled Yalkus, Yelkes, Yelkis, Yal-kus, and Yelcus)…

-

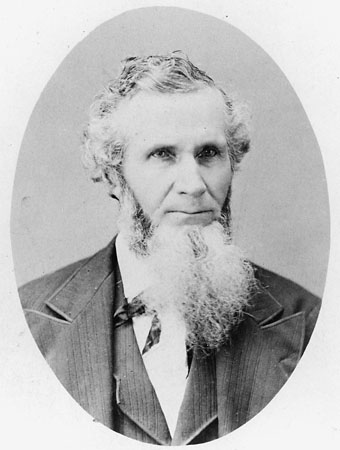

![Joel Palmer (1810–1881)]()

Joel Palmer (1810–1881)

Joel Palmer spent just over half of his life in Oregon. He first saw th…

-

![Kathryn Harrison (1924-2023)]()

Kathryn Harrison (1924-2023)

Kathryn Jones Harrison of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde was on…

-

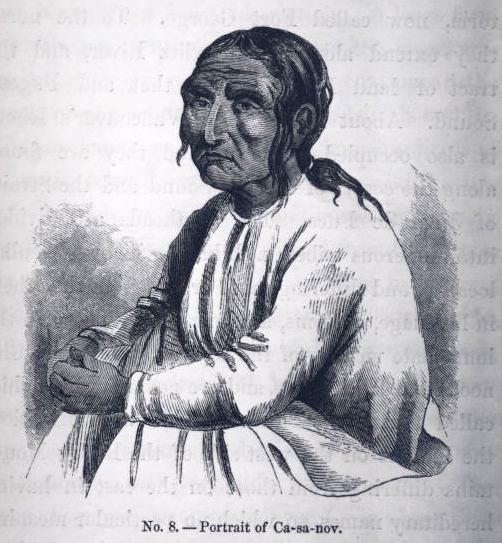

![Kiesno (Chief Cassino) (1779?-1848)]()

Kiesno (Chief Cassino) (1779?-1848)

Chief Kiesno (his name has also been spelled Keasno, Casino, Kiyasnu, Q…

-

![Molalla Peoples]()

Molalla Peoples

The name Molalla ([moˈlɑlə, ˈmolɑlə], usually spelled Molala by anthrop…

-

![Willamette Valley Treaties]()

Willamette Valley Treaties

From 1848 to 1855, the United States made several treaties with the tri…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Berman, Howard. "The Position of Molala in Plateau Penutian." International Journal of American Linguistics 62.1 (1996):1-30.

Chapman, Judith Sanders, and Lois E. Helvey Ray. Molalla. Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2008.

Drucker, Philip. Volume 1 Notebook 4516-78 (Coos & Molalla): National Anthropological Archives, 1934.

Guyer, R. J. Douglas County Chronicles: History from the Land of One Hundred Valleys. Stroud, U.K. History Press, 2013.

Hymes, Dell. "The Earliest Clackamas Text." International Journal of American Linguistics 50.4 (1984): 358-383.

Olson, Kristine. Standing Tall: The Lifeway of Kathryn Jones Harrison, chair of the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, University of Washington Press, 2005.