Chemawa Indian School, located in the mid-Willamette Valley north of Salem, is one of four remaining off-reservation boarding schools funded and operated by the federal Bureau of Indian Education (BIE). It is an accredited high school, with grades nine through twelve. The school provides academic classes, athletics, support services, and Native cultural programs and activities. Students are from reservations and communities in the western United States and Alaska. Enrollment requires membership in a federally recognized tribe or Alaska Native village, as all BIE schools do. In recent years, Chemawa has averaged around three hundred students.

Early History, 1880–1885

Beginning in the 1850s, as the United States government negotiated with many tribes, treaty provisions often included the promise of schools. By the 1870s, the government had established day and boarding schools on many reservations, often collaborating with churches. In the early years, some Native leaders and families agreed to send their children to the schools. hoping they would gain skills to help their tribes. But as federal agents began to force attendance, escapes from the schools and absenteeism became common. In 1879, the Bureau of Indian Affairs implemented a new system of federally operated “industrial and training” schools for Native children, usually located some distance from the students’ homeland. These off-reservation boarding schools were intended to separate children from their families and tribes so they could be controlled and influenced more effectively.

The first two of these institutions were founded months apart and were supervised by U.S. military officers—Richard Henry Pratt at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and Melville C. Wilkinson at Forest Grove, Oregon. Wilkinson had recently served as the aide-de-camp to General Oliver Otis Howard, who led military operations against the Nez Perce and other Northwest tribes. Wilkinson believed, as did Pratt, that Indians could be better conquered with education and religion than with bullets, but that “education” was as destructive as death for many Native children. Pratt’s phrase, “Kill the Indian and save the man”—that is, destroy the culture and salvage the person—was a common view among social reformers in 1880.

The Forest Grove Indian Training School opened in February 1880 when Wilkinson escorted the first students—eighteen of them—from the Puyallup Reservation in Washington Territory. The school was on a four-acre block of land owned by Pacific University. Only one building had been constructed before their arrival, and Wilkinson swiftly put the oldest students, who were in their late teens and early twenties, to work constructing more buildings and furnishings.

The school was funded on a per capita basis, to increase funding, and Wilkinson brought cohorts of students from tribes across the Pacific Northwest and Alaska. Children as young as six were forcibly removed from their homes and sent to boarding schools, far distant from their families, tribes, and villages. Brought for a term that could last from three to ten years, their clothes were replaced with military-style uniforms, their hair was cut, and they were forbidden to speak their Native languages. From 1880 to 1885, 310 students from two dozen modern tribal nations were enrolled at Forest Grove. They generally spent about half each school day in academic classes and the other half in vocational training.

Academics were cursory, emphasizing basic competence in reading and writing English. Vocational training was designed to prepare students for trades or domestic work, such as carpentry, shoemaking, farming, laundry, and cooking. At the same time, however, the students’ labor in these tasks was critical to the daily upkeep of the school. Boys learning carpentry built most of the school buildings, while the girls did nearly all of the cooking, serving, washing, and sewing. Most of this labor was unpaid. Other activities included military drills and athletics and compulsory attendance at the local Congregational church.

With only four acres of land, the Forest Grove Indian School had to rent fields to support its farming program. Soon after his arrival in 1883, the second superintendent, Dr. Henry J. Minthorn, lobbied for a larger campus. The BIA agreed to relocate the school on the condition that new land would either be donated directly to the government or purchased through donations. Minthorn took up a donation from the students themselves, who gave at least $550 of their own savings toward a new site for the school. With that money and additional donations, Minthorn purchased just over 177 acres five miles north of Salem—and, federal records claim, “donated by the citizens of Salem.”

Forest Grove residents objected to the move, but they had little political clout compared to Salem businessmen who wanted the school’s federal dollars to be spent nearer their city. The day after the deed for the new Chemawa campus was signed over to the U.S. government, the girls’ dormitory in Forest Grove burned to the ground. Support for keeping the school in Forest Grove collapsed, and administrators began moving students to the new site in March 1885. The campus buildings in Forest Grove were eventually demolished and residential homes were built on the site. There are no visible remains of the school in the city.

Chemawa, 1885–present

“Chemawa” is a Santiam Kalapuyan place-name that means “low-lying, frequently overflowed ground.” The name was also given to a post office and station next to the Oregon and California Railroad tracks on the east edge of the first acreage. The school’s name changed over the years, from the U.S. Indian Industrial and Training School at Salem (1885–1891); to the Harrison Institute (1891–1893); to Salem Indian School at Chemawa (1893–1939); and finally to Chemawa Indian School (July 1, 1939–present).

Superintendent W. V. Coffin reported that the school at Salem opened on June 1, 1885, but no new buildings were available until April 1886. Students arriving in the spring of 1885 cleared the land of stumps, small trees, and brush left when the property was logged. No school buildings had been constructed, and they lived in an old farmhouse and stable and rough sheds they made from timber on the site. The school had a cemetery with several graves, with the first 177 acres augmented in 1887 with an additional 84 acres east of the tracks, purchased with funds earned by students who picked hops in the valley.

As at Forest Grove and other Indian industrial training schools, Chemawa students were taught agricultural, mechanical, industrial, and domestic skills along with some formal education, although the curriculum minimized literacy and mandated military regimentation, obedience, and servitude. Uniforms and marching were the norm for decades. Boys attended courses in farming, painting, baking, shoemaking, drafting, machining, blacksmithing, and masonry. Girls were taught to sew, cook, launder, make beds, and sweep floors. All school operations depended on their labor, and all students were placed as laborers, servants, or cooks in “outing” programs in local businesses, farms, and homes.

While there were elementary day schools on reservations, secondary education was usually unavailable and racism prevented many Native children from enrolling in local schools.

In the first decades of the twentieth century, some Native families voluntarily sent their children to government or church-operated boarding schools because they offered opportunities not

available on reservations or in Alaskan villages.

By 1924, the year Native Americans were granted U.S. citizenship, Chemawa resembled a small town. The campus plant had grown to over 450 acres, with gardens and orchards, cultivated fields, and a dairy barn. There were seventy buildings, including an administration building, boys and girls dormitories, industrial arts and domestic science buildings, a gymnasium, a bakery, and a large hospital. The campus buildings were on both sides of the railroad tracks near what is now the Interstate 5–Chemawa Road exit. The campus extended south from Chemawa Road, west as far as the Burlington Northern Railroad, south to Keizer Road, and east to the Labish Ditch.

After World War I, educational policies changed as political views and social values shifted. In 1927, enrollment in twelve grades peaked at 1,100 pupils, although the recommended capacity was about half that number. As the years passed and funding grew, classes more closely resembled white public schools. Extracurricular activities included an athletic program, debating and literary societies, and a band.

While Indian boarding schools increased their enrollment in the early 1900s, by the early 1930s the government began to question their costs and effectiveness. Nevertheless, forced enrollment of Native children in boarding schools was still common in the 1960s, particularly in Alaska. Funding for Indian education was periodically slashed, and Chemawa was threatened with closure in 1933, 1947, and the 1960s. Public schools were gradually opened to Indian students, and the establishment of tribal schools on reservations diminished the demand for schools like Chemawa. But by the 1960s, the school had become an important part of Northwest Native culture, and through the efforts of tribal leaders, alumni, Salem residents, and Oregon politicians, Chemawa prevailed.

In the 1970s, $10 million was allotted for a new campus complex and an Indian Health clinic on the east side of the property. As the Salem region grew, Interstate-5 (dedicated in 1966) and local

highway expansion reduced the campus to fewer than 300 acres, and the original school buildings were demolished. In 1992, the historic campus—about 79 acres, including the old hospital and cemetery—was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. The last structure on that site, the Chemawa hospital and clinic, had been built in 1907 and burned in 1995. In 2009, a new dormitory for four hundred students was constructed.

Over the last part of the twentieth century, emphasis on Native culture was finally integrated into school curriculum and activities, and pow wows became a part of the school tradition. Off-reservation boarding schools became unintended models for cultural diversity and contributed to the growth of Native and tribal identity. Students from many tribes formed Pan-Indian friendships, marriages, and families, and many sent their children and grandchildren to Chemawa.

Academics, with a focus on computers and digital technology, have supplanted industrial and manual labor training at Chemawa. Class discussions now consider Native history, tribal sovereignty, language preservation, and cultural diversity. Powwows are held regularly, and Willamette University in Salem has established a mentoring program to encourage students to pursue higher education. School operations are managed by the Bureau of Indian Education and the school land, including the historic campus site and Chemawa Cemetery, is under the jurisdiction of the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Chemawa still faces challenges, including inadequate funding, struggles with staffing, internal conflicts, student safety, public criticism, and its history of bureaucratic indifference. Despite the efforts of staff, alumni, and advocates, the future of the school remains a question. Precautions against COVID-19 emptied the campus and forced a shift to virtual classes, but a limited number of students returned to the campus in October 2021.

Deaths and Burials

In May 2021, the discovery of unmarked graves at residential schools in Canada sparked media interest and public questions about the history of Indian boarding schools in the United States and Alaska. Recent studies on the impact of these schools reveal a complex and tragic past. While some children thrived, others barely survived. Many, as evidenced by cemeteries at nearly all the schools, died. Survivors of these institutions and their descendants now confront a history of abuse and neglect. In June 2021, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland announced the Federal Indian Boarding School initiative to “address the inter-generational impact of Indian boarding schools to shed light on the unspoken traumas of the past.” A primary goal is to locate and

identify all such facilities and burial sites and to determine the “identities and Tribal affiliations at such locations.”

Chemawa is not exempt from this legacy. No longer used for student burials after 1940, the Chemawa cemetery was razed in 1960, and the grave markers were replaced based on a map kept at the school. Some markers were lost, and teachers, staff, students, and local tribes have held many ceremonies of remembrance for the children buried there. Individual student files have been kept at the National Archives and Records Administration in Seattle. In the early 1990s, the Willamette Valley Genealogical Society compiled a list of the burials and death certificates of Chemawa students. Chemawa historian and researcher SuAnn Reddick and Pacific University Archivist Eva Guggemos compiled and cross-checked enrollment records and individual files with the cemetery map and compiled a list of all the known deaths and burials at the school since 1880. On October 11, 2021, Indigenous Peoples Day, Pacific University in Forest Grove published “Deaths at Chemawa Indian School,” featuring the cemetery spreadsheet.

-

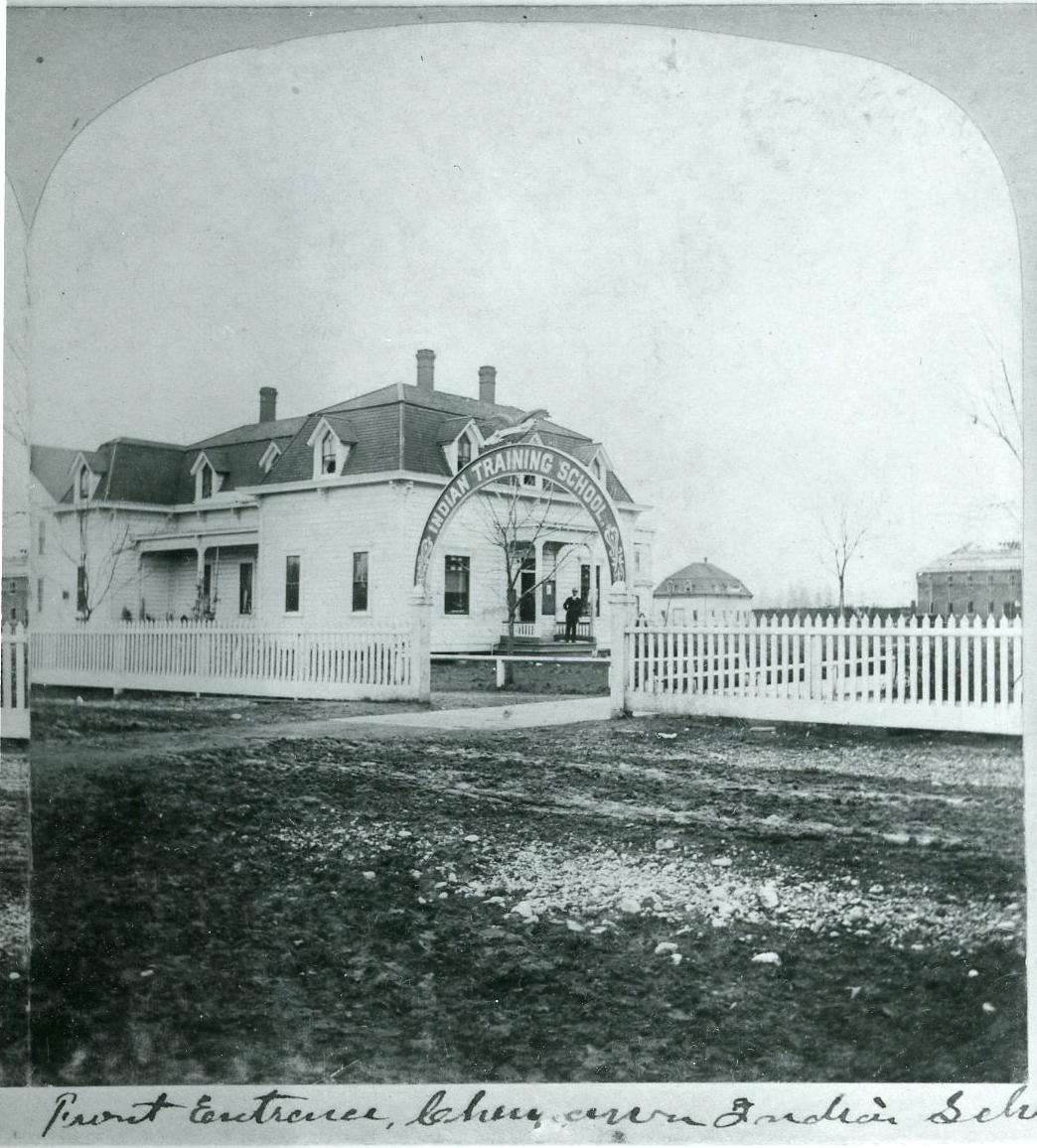

![]()

Students standing at the entrance of the Chemawa Indian Training School in Salem.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, bb003857

-

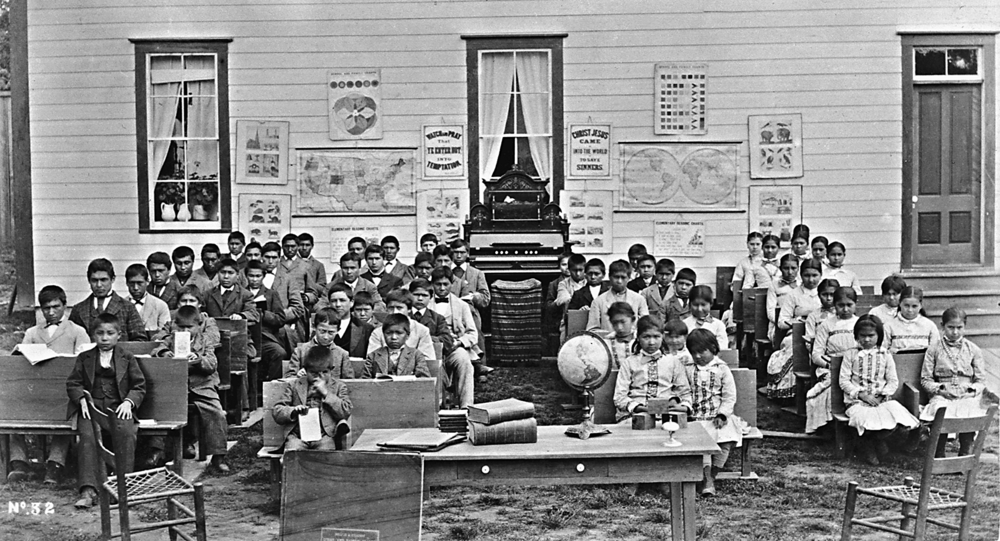

![]()

Students and staff at Chemawa, 1887. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 0182g038..

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 0182g038

-

![]()

Wooden eagle on the arch over the front entrance to Chemawa, c.1900.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 016492

-

![]()

Girls dormitory at the Chemawa Indian Boarding School, 1905.

Postcard, Oreg. State Univ. Lib., Gerald W. Williams Coll.

-

![]()

Boys dormitory at Chemawa Indian Boarding School, 1901.

Northwest Museum of Arts & Culture, Eastern Wash. Univ., ER4.7.3

-

![]()

Aerial view of Chemawa grounds, 1887.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 0173G029

-

![]()

Buildings and grounds at Chemawa, 1887.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib. 0173G017

-

![]()

Students and instructors in the Chemawa machine shop, 1887..

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 0173G027

-

![]()

Chemawa girls sitting on school steps, c.1928. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Alice Judd Coll. 492..

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Alice Judd Coll. 492

-

![]()

Chemawa school play, c.1928. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Alice Judd Coll. 492..

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Alice Judd Coll. 492

-

![]()

Teacher Alice Judd and Chemawa teenagers, c.1928. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Alice Judd Coll. 492..

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Alice Judd Coll. 492

-

![]()

Chemawa Indian School Cheerleaders, 1949.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., CN007202

-

![]()

Chemawa students, c.1928. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Alice Judd Coll. 492..

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Alice Judd Coll. 492

-

![]()

Girls learn loom weaving at Chemawa, 1937. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, bb003867..

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, bb003867

-

![]()

Young women from Chemawa trained at the Eugene National Youth Administration for skilled work in the Portland shipyards, 1942.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Journal, 013610

-

![]()

View across a field of Chemawa, 1907. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi45267..

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi45267

-

![]()

Students of Reliance Literary Society, Chemawa, 1887. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 0173G015..

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 0173G015

-

![]()

Non-Native officials at Chemawa, 1887. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 0173g018..

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 0173g018

-

![]()

Students at Chemawa dining hall, c.1887. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 0173G010..

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 0173G010

-

![]()

Students on Chemawa grounds, 1887. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 0173G012..

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 0173G012

-

![]()

Chemawa students, 1887. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 0173G020..

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 0173G020

Related Entries

-

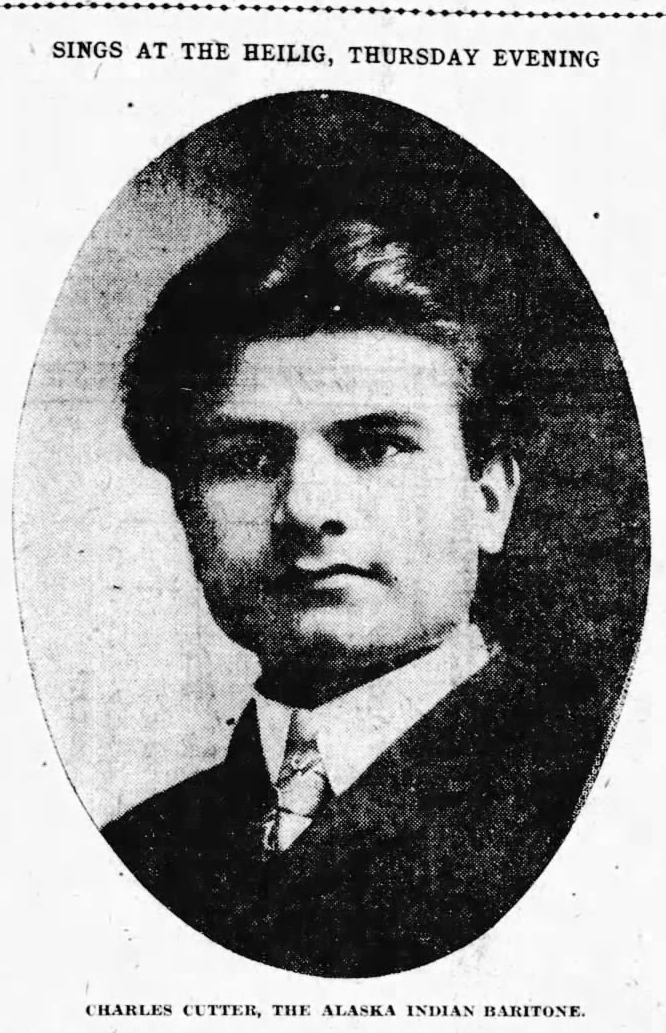

![Charles Cutter, aka Chief Eagle Horse (1878–1938)]()

Charles Cutter, aka Chief Eagle Horse (1878–1938)

Charles Cutter, whose Tlingit name was Dockh-hoh-kharckh, was an actor …

-

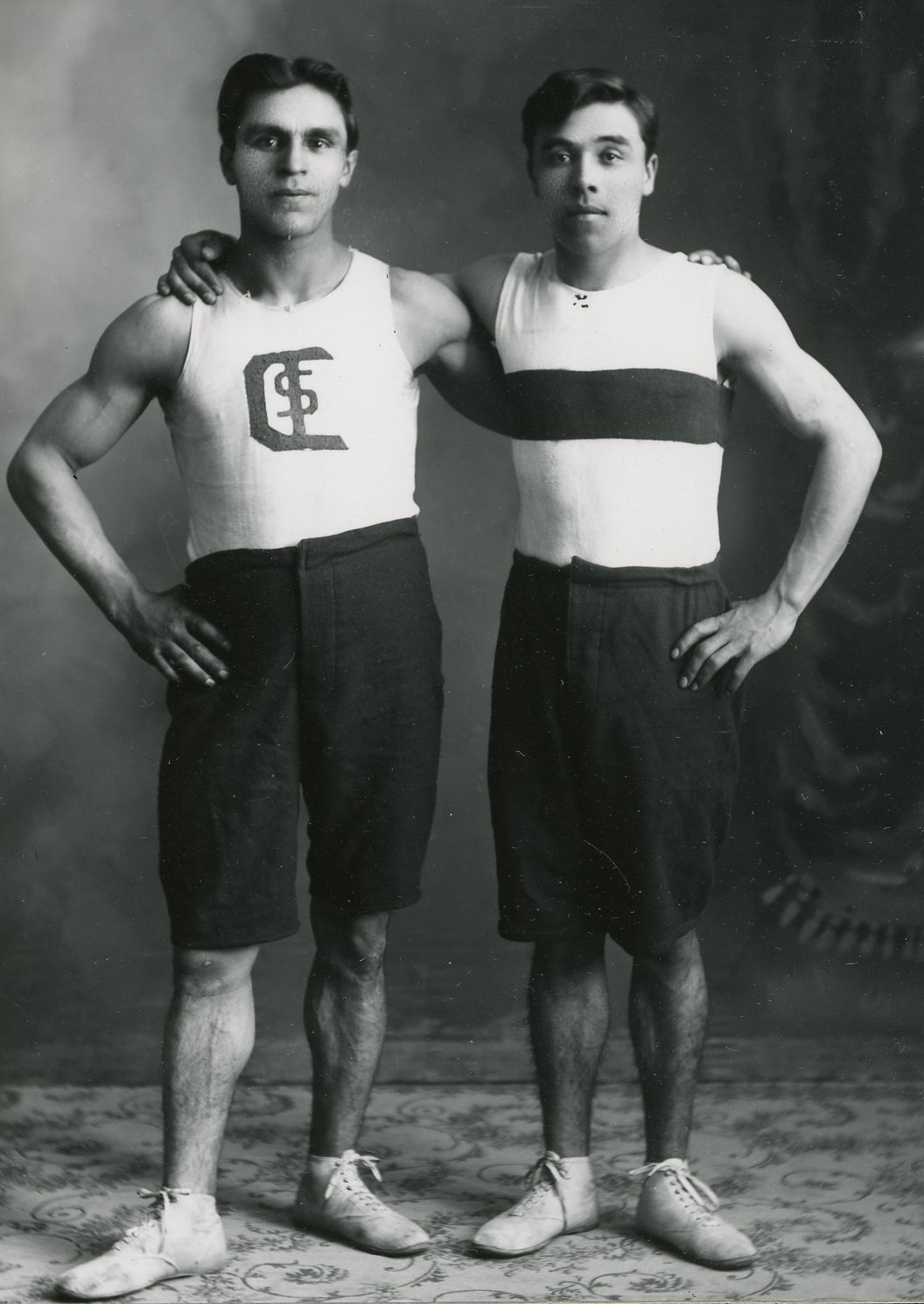

![Chemawa Indian School Athletics Program]()

Chemawa Indian School Athletics Program

Chemawa Indian School has been a leader in organized athletics in the W…

-

![Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde]()

Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon is a confede…

-

Indian Boarding Schools

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, only one Indian boarding …

-

![Pacific University]()

Pacific University

Pacific University, one of the oldest universities in the American West…

-

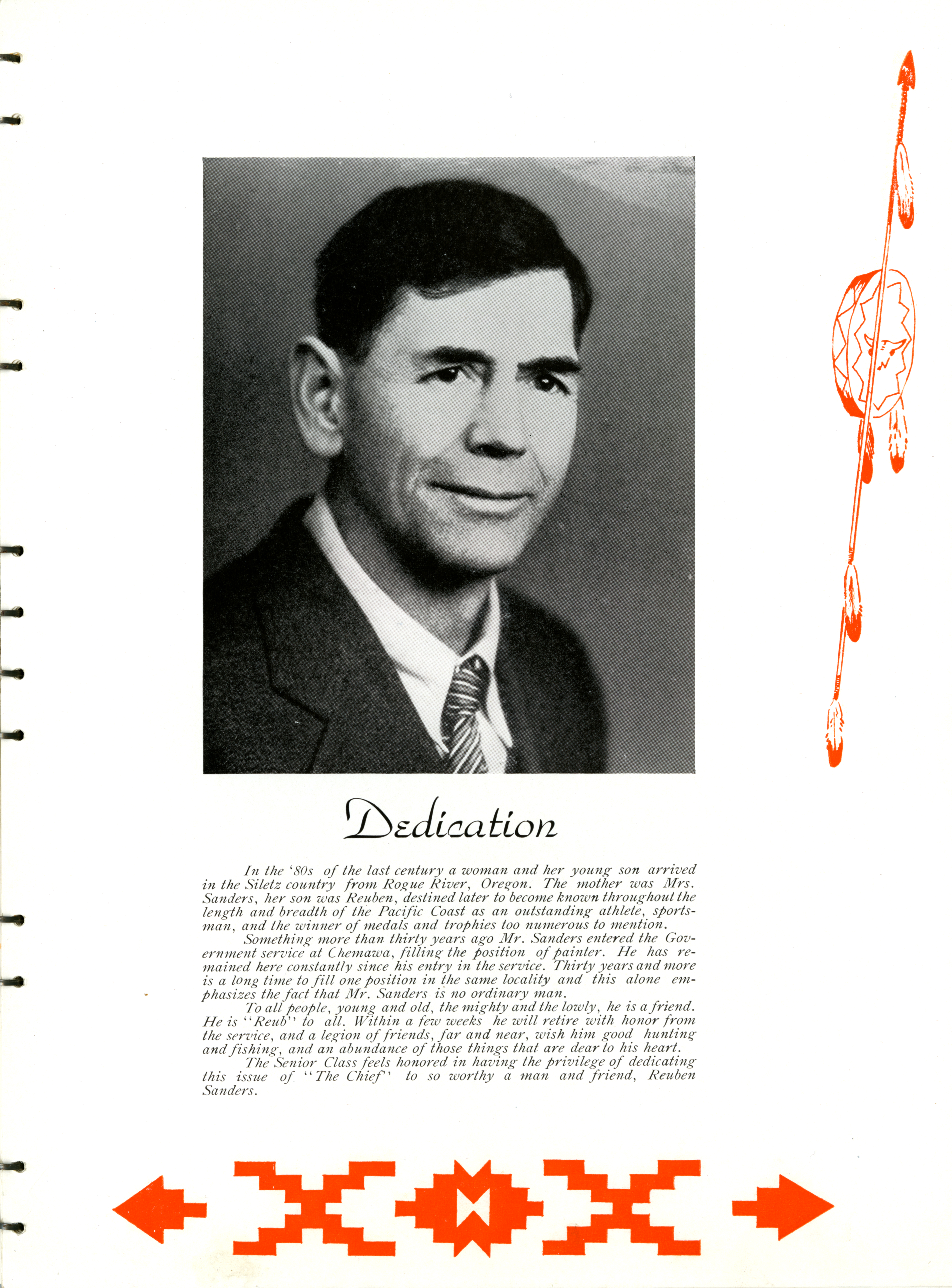

![Reuben C. Sanders (1876–1957)]()

Reuben C. Sanders (1876–1957)

Reuben “Reub” C. Sanders was one of Oregon’s greatest all-around athlet…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Adams, David Wallace. Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875–1928. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1995.

Bonnell, Sonciray. Chemawa Indian Boarding School: The First One Hundred years, 1880 to 1980. Universal Publishers, 1997.

Collins, Cary C. “Through the Lens of Assimilation: Edwin L. Chalcraft and Chemawa Indian School.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 98 (Winter 1998): 390–425.

Child, Brenda J. Boarding School Seasons: American Indian Families, 1900-1940. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999.

Lajimodiere, Denise K. Stringing Rosaries: The History, the Unforgivable, and the Healing of Northern Plains American Indian Boarding School Survivors. Fargo: North Dakota State University Press, 2019.

Lomawaima, K. Tsianina. They Called it Prairie Light: The Story of Chilocco Indian School. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994.

Lemmon, Burton Carlyle. “The Historical Development of Chemawa Indian School.” M.A. thesis, Oregon State College 1941.

McKeehan, Patrick Michael. The History of Chemawa Indian School. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1981.

Reddick, SuAnn M. “The Evolution of Chemawa Indian School: From Red River to Salem, 1825–1885.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 101 (Winter 2000): 444–465.