Miluk was one of two related languages spoken by people known collectively as Coos. Miluk speakers comprised two distinct bands, one on Coos Bay and one on South Slough and the lower Coquille River. The Coos Bay/South Slough Miluk people lived in several autonomous villages along lower Coos Bay (south of the Empire District), South Slough, and Cape Arago. The Lower Coquille people (also known as Nasomah) lived in three principal villages near the mouth of the Coquille River.

The Miluk were also known by other names, such as the Gwisiiya, which means ‘toward the south, southerners’ in Miluk and the closely related Hanis Coos language, and as the Dalmashi by the Athabaskan-speaking Upper Coquille people who lived upriver. The culture and political structure of the two bands were similar. Each village had a headman who adjudicated disputes inside the village and between villages, helped make sure everyone had sufficient resources, and helped host or arrange events such as dances, games, ceremonies, and trade with other tribes.

The Miluk language is similar in many respects to Hanis, the language spoken on the rest of Coos Bay and as far north as Tenmile Lake along the Coos-Douglas county line. The degree of relationship between the two languages is still debated today. Melville Jacobs, a linguist from the University of Washington who worked with Annie Peterson—the last known fluent speaker of both Hanis and Miluk—in 1933 and 1934, thought the two languages were “perhaps as close as, or, to use a rough analogy, closer than Dutch and High German.” Miluk is classified as part of the Coast Oregon Penutian, which in addition to the Coosan languages includes the Siuslawan and Alsea languages to the north. Annie Peterson left behind the fullest record of the Miluk language in her work with Jacobs, which includes over a hundred texts. She grew up knowing Miluk speakers from both Coos Bay and Nasomah and may have freely used words from both dialects.

The earliest record of the Miluk language was in 1884 when James Owen Dorsey wrote down approximately a hundred and thirty words and phrases of Nasomah dialect, the only linguistic material ever captured specific to this dialect. Additional sources include a list of about two hundred words that Harry Hull St. Clair recorded from George Barney, of South Slough descent, in 1903; fewer than a hundred words from various informants in 1942 in interviews with John Peabody Harrington of the Bureau of American Ethnology; and a sound recording in 1953 with the last living fluent speaker of Miluk, Laurie (Lolly) Metcalf.

The Miluk peoples lived in a rich estuarine and coastal environment that provided diverse resources for food, medicine, and material culture. While the permanent villages of the Miluk Coos and Nasomah were near the coast, Miluk Coos on the lower main bay had seasonal upriver fishing camps on the South Fork of Coos River. Large permanent dwellings were semi-subterranean buildings of red-cedar planks and support posts that were usually Douglas-fir. The walls and floors were often covered with tule (Schoenoplectus sp.) mats. Storage sheds—also made of red-cedar planks or sometimes roofed with a sedge (Scirpus microcarpus) called mǝ´qmi—stored firewood, tools, and some basketry materials. Twined basketry was used for storage and cooking receptacles, fish traps, mats, and clothing. Baskets were so important that in Miluk there were more than two dozen names for different types.

Miluk people, like their Hanis neighbors, built two types of sweat lodges: the kwǝ´llǝtł’, a small above-ground sweat lodge made of bent poles and covered with tule mats, and a semi-subterranean red-cedar plank sweat lodge called a gɨsk’ɛt. The kwǝ´llǝtł’ was used by small groups of women (usually no more than four). The gɨsk’ɛt was used for men preparing to hunt or for healing and also was a dormitory for young unmarried men.

At certain times of the year, Miluk traveled to trade. Hanis and Miluk from Coos Bay met Nasomah annually in late spring near Whiskey Run to gather camas and brodiaea harvest lilies. Many also traveled east to Camas Valley to trade and also to the Columbia River region and present-day northern California. Through trade, they obtained items such as high-prow canoes, obsidian, grey pine nuts (Pinus sabiniana) for beads, dentalia, and clam shell disc beads.

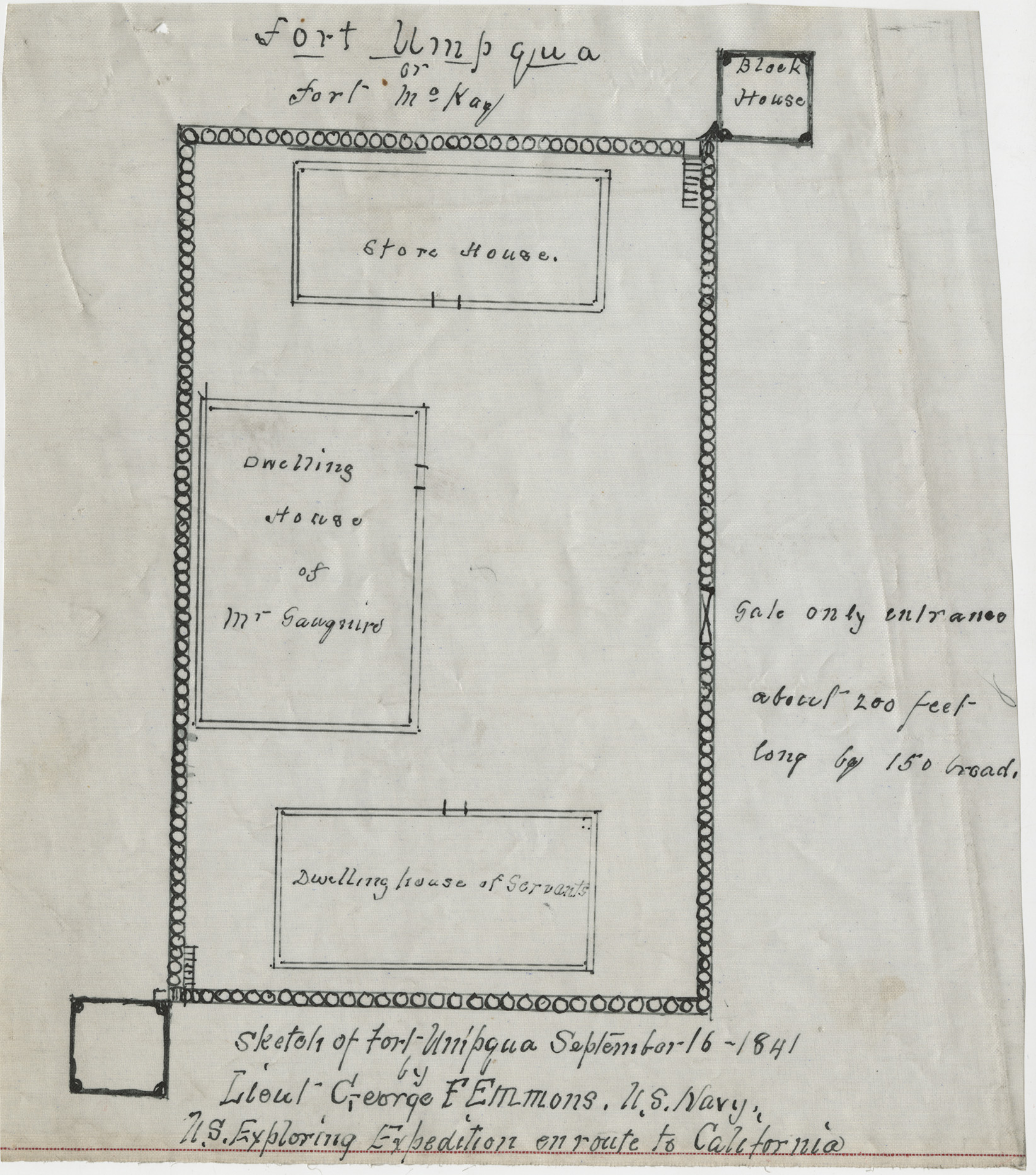

The first known encounters for Miluk with Europeans was in the early nineteenth century. In 1828, Jedediah Smith’s expedition passed through Coos Bay, and parties of fur traders affiliated with the Hudson’s Bay Company occasionally came as far south as Coos Bay and the Umpqua Valley. In 1836, HBC established a small trading post, Fort Umpqua, where Elkton is today. Encounters with non-Natives tended to be sporadic until the 1850s, when non-Native settlers became more interested in the region.

After white miners found gold just north of present-day Bandon, on Whiskey Run beach, the mining settlement of Randolph was founded there in 1853. The miners caused conflicts with local Natives, especially the Nasomah who lived closest to Randolph. They committed appalling acts of violence against the Nasomah, from murder to rape. On January 28, 1854, one group of miners attacked a Nasomah village. Indian Agent F. M. Smith reported that fifteen men and one woman were killed and two women were badly wounded.

Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer had the authority to negotiate a treaty with the coastal tribes, and in 1855 the Coos Bay Miluk (which were listed along with the Hanis collectively as "Kowes Bay Tribe") and forty-two Nasomah men were among the signers. Congress never ratified the treaty. A year later, when war had heated up between white resettlers and southern Oregon tribes, Coos Bay people were forcibly removed by the federal government to a military fort on the Umpqua River. In June 1856, fifty or sixty Nasomah were held near Port Orford along with hundreds of Indians from the Upper Coquille and Curry County bands to be removed by ship and eventually relocated to the Siletz Agency of the Coast Reservation.

In 1860, the process began to remove the Coos Bay again to the Alsea Subagency of the Coast Reservation, along with the Lower Umpqua. Some Indigenous women were allowed to remain in southern Oregon if they were married to white men, and many of those couples sheltered relatives who resisted removal or escaped from reservations. The conditions of illness and starvation were terrible during this time. In 1860, an Indian agent at the Alsea Subagency estimated there were a total of 180 Coos Bay (combining the Miluk-speaking and Hanis-speaking Coos people), 99 Lower Umpqua and 104 Siuslaw people in his jurisdiction. In 1872, the reported numbers were 110 Coos Bay and 40 each Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw, a drop in population of about 50 percent.

When the Alsea Subagency was closed in 1876, many Coos Bay and Lower Umpqua people, instead of moving to the Siletz Agency, moved to the Siuslaw River—which created an intertribal community of Siuslaw, Lower Umpqua, and Coos Bay people—or back to their ancestral homelands. The Siletz Agent in 1876, William Bagley, visited the subagency in July 1876, but the Coos Bay and Lower Umpqua people avoided him since they did not wish to move to Siletz. Bagley estimated there were about two hundred Coos Bay, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw people living off reservation.

Many Miluk people returned to South Slough on Coos Bay or lived in Empire (today a part of the City of Coos Bay). Some tried to claim homes under the Homestead Act. In the 1890s, many were able to file for Indian allotments on the Siuslaw River, Umpqua River, and in Coos County. Today, descendants of the Miluk Coos and Nasomah are enrolled predominantly with the Coquille Indian Tribe, the Confederated Tribes of Siletz, and the Confederated Tribes of the Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw.

-

![]()

The Coquille Tribe celebrated tribal restoration in 1989 with speeches and ceremonies in Bandon near the site of the Na So Mah village..

Courtesy Bandon Historical Society

-

![]()

The Coquille tribe held a salmon bake and Pow Wow on Port of Bandon property in 1991..

Courtesy Bandon Historical Society

Related Entries

-

![Alsea Subagency of Siletz Reservation]()

Alsea Subagency of Siletz Reservation

In September 1856, Joel Palmer, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs fo…

-

![Camas]()

Camas

Camas is a North American bulb-forming geophyte whose greatest diversit…

-

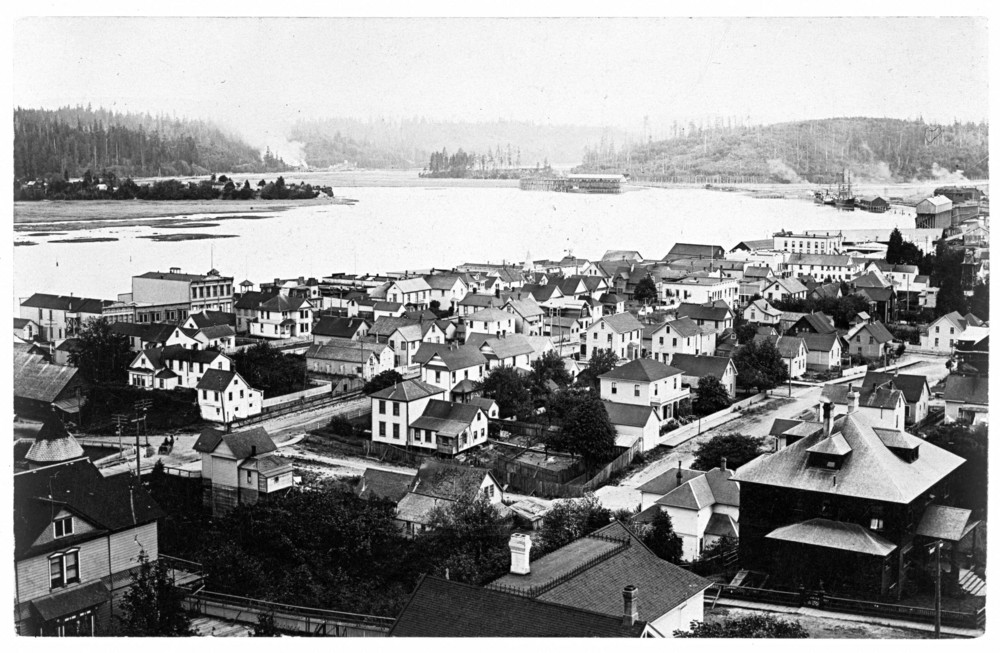

![Coos Bay]()

Coos Bay

The Coos Bay estuary is a semi-enclosed, elongated series of sloughs an…

-

![Fort Umpqua (HBC fort, 1836-1853)]()

Fort Umpqua (HBC fort, 1836-1853)

Fort Umpqua was a small but important post in the Hudson’s Bay Company’…

-

![Hanis Coos (Kowes)]()

Hanis Coos (Kowes)

The Hanis (hanıs) people lived in villages along Coos Bay, Coos River, …

-

![Jedediah Strong Smith (1799-1831)]()

Jedediah Strong Smith (1799-1831)

Jedediah Strong Smith was one of the first and, arguably, the most impo…

-

![Joel Palmer (1810–1881)]()

Joel Palmer (1810–1881)

Joel Palmer spent just over half of his life in Oregon. He first saw th…

-

![Melville Jacobs (1902-1971)]()

Melville Jacobs (1902-1971)

Melville Jacobs did more to document the languages, cultures, oral trad…

-

![Nasomah Massacre of 1854]()

Nasomah Massacre of 1854

Early explorers noted plankhouse structures up and down the Southern Or…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

"Laura 'Lolly' Hodgkiss Metcalf speaking Miluk." www.miluk.org

Beck, David R. M. Seeking Recognition: The Termination and Restoriation of the Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw Indians, 1855-1984. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009.

Beckham, Stephen Dow. “Lonely Outpost: The Army's Fort Umpqua.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 70.3 (1969): 233–57.

Hall, Roberta. People of the Coquille Estuary. Corvallis, Ore.: Words & Pictures Unlimited, 1995.

Jacobs, Melville. Coos Narrative and Ethnologic Texts. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1939.

Jacobs, Melville. Coos Myth Texts. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1940.

O'Donnell, Terence. An Arrow in the Earth: General Joel Palmer and the Indians of Oregon. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 1991.

Phillips, Patricia Whereat. Ethnobotany of the Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw Indians. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2016.