The possible wreck of a European ship at Point Adams, on the southern edge of the Columbia River estuary, has long fascinated Oregonians. The ship—known as the “Konapee wreck” from the purported name of a survivor, as given by Clatsop and Chinook tradition-bearers—may have run aground before first recorded European contact and is known only through Native recollections.

The earliest written account that might reference the Konapee wreck appears in Pacific Fur Company apprentice clerk Gabriel Franchère’s 1811 description of a conversation he had with a Native during his voyage on the lower Columbia: “Our guide said that he was a white man, and that his name was Soto. We learned from the mouth of the old man himself, that he was the son of a Spaniard who had been wrecked at the mouth of the river; that a part of the crew on this occasion got safe ashore, but were all massacred by the Clatsops, with the exception of four, who were spared and who married native women.” This account does not mention Konapee or other circumstances of the wreck referred to in later anthropological sources.

George Gibbs’s report to the U.S. Department of the Interior in 1877 provides the earliest anthropological account that refers to the wreck, though there is no mention of any survivors by the name of Konapee. Gibbs also seems to have been the first to expand the details related to Soto, whom Franchère met in his journey. Gibbs quotes communications he had with Celiast, born about 1810, who was the daughter of Clatsop Chief Coboway and the wife of pioneer Solomon H. Smith. She recounted to Gibbs that the first whites seen by the Clatsop were three men (one of whom soon died) who came ashore from a wrecked vessel. People from nearby villages burned the vessel to retrieve the metal, and the two survivors remained as slaves to the Clatsop until it was discovered that one was “a worker in iron.” Both the castaways departed for their own country toward the east, her account continues, and went as far as The Dalles; one returned to Multnomah Island and married there. Gibbs added: “The man who lived on Multnomah Island was undoubtedly the one mentioned by Franchère in his narrative, whose son, Soto, was alive, and a very old man, at the time of his visit.”

A similar account by Chinook Native Charles Cultee, transcribed by anthropologist Franz Boas in 1894, is the second earliest anthropological description. It describes the ship seen by a mourning Clatsop woman: “two spruce trees standing upright on it...its outer side was all covered with copper. Ropes were tied to those spruce trees and it was full of iron.” There were two men on board, he said, who were taken as slaves by the Clatsop, one kept by each chief. The Clatsop burned the ship and gathered the iron, copper, and brass that remained.

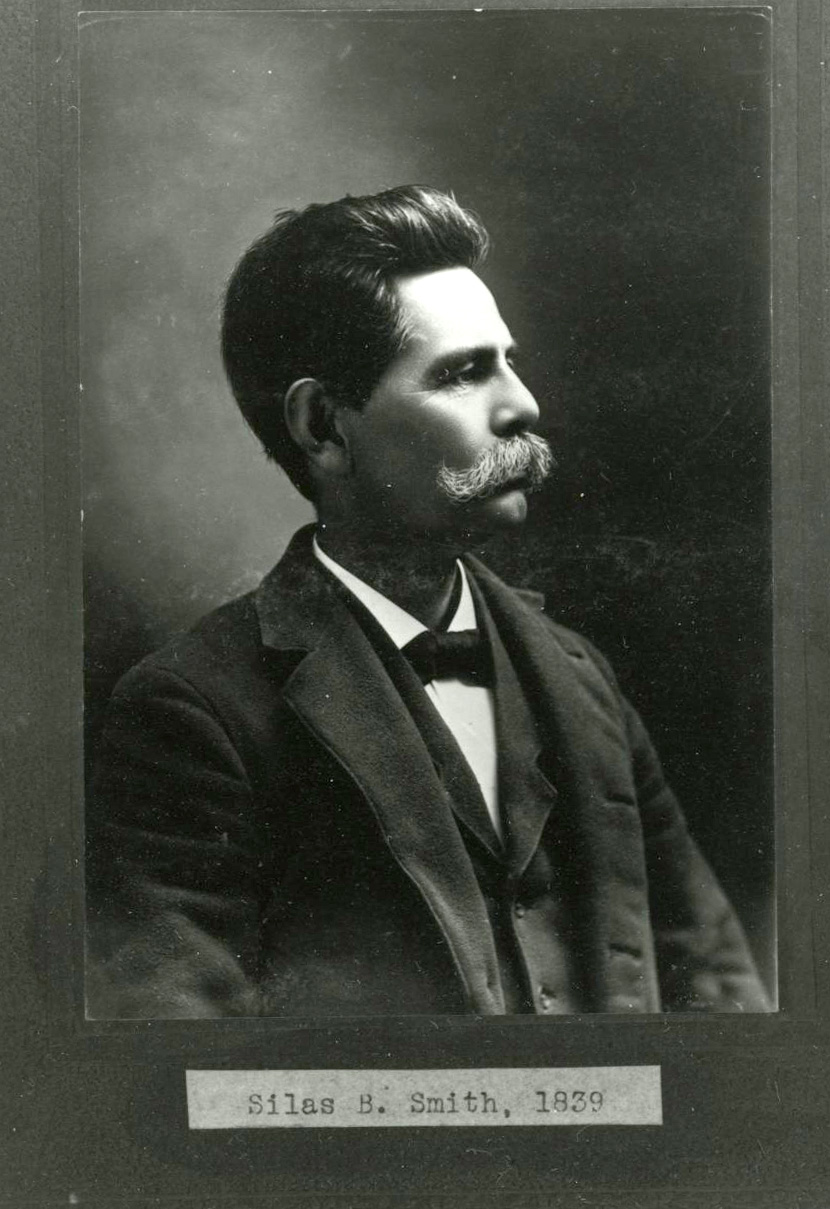

Silas Smith, Celiast’s son, was a trained historian and lawyer who wrote an influential article in 1900 that added important details. Smith mentioned two survivors of the wreck. He was the first to say that one of the survivors was called, in the local language, “Konapee.” Given his freedom because of his skill as a blacksmith, Konapee and his companion went upriver “to a place now known as New Astoria....After that the Indians called the place Konapee...the men always declared that their home was toward the rising sun. And after a year or two they started east up the Columbia river, but, after reaching the Cascades, they went no further and there intermarried with the natives.” Smith, like Gibbs, conjectured that Soto was Konapee’s son.

The tradition of this shipwreck, including the village, is mentioned in later accounts as well. Edward Curtis, in The North American Indian, mentions Kunupí as a Clatsop village situated “about a mile above Fort Stevens, Oregon,” and historian J. Nielson Barry summarized the main elements of the Konapee story in the Washington Historical Quarterly in 1932. Using Franchère’s original account, Barry mentioned four survivors of the wreck, rather than two or three.

Anthropologists and historians have often pointed out that similarities in the accounts make it likely that they all concern a single shipwreck, though there is no external evidence that this is the case. The Point Adams area has been greatly modified by the 9.7- mile-long Columbia River South Jetty, constructed between 1885 and 1939. The jetty caused a tremendous accretion of sand to the north and west, now called Clatsop Spit, which both enlarged and engulfed the old Point Adams. No trace of any early European wreck has been found in the region, but the dramatic change to the southern mouth of the Columbia makes it unlikely that any physical remains will ever be accessible.

The Konapee wreck entered newspaper accounts, popular histories, and literary works. Articles in the Oregonian and other newspapers, trawling the legendarium of coastal mysteries, usually mentioned Konapee. Daniel Franklin Howard (1841-c.1933), a settler in Stella, Washington, wrote a “complete historical novel,” Oregon’s First White Men (1927), plus a “scenario of dramatical composition” and a lengthy poem, all imaginative depictions based on Native legends and European histories he researched about the Konapee wreck.

Though recorded with vague and fluctuating details, the tradition of the Konapee wreck remains an important marker in Oregon history. Factually incomplete as they are, stories of the Konapee wreck open a window onto Native-European interactions before documented EuroAmerican explorers and settlers arrived in present-day Oregon.

-

![]()

Silas B. Smith.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 024439

-

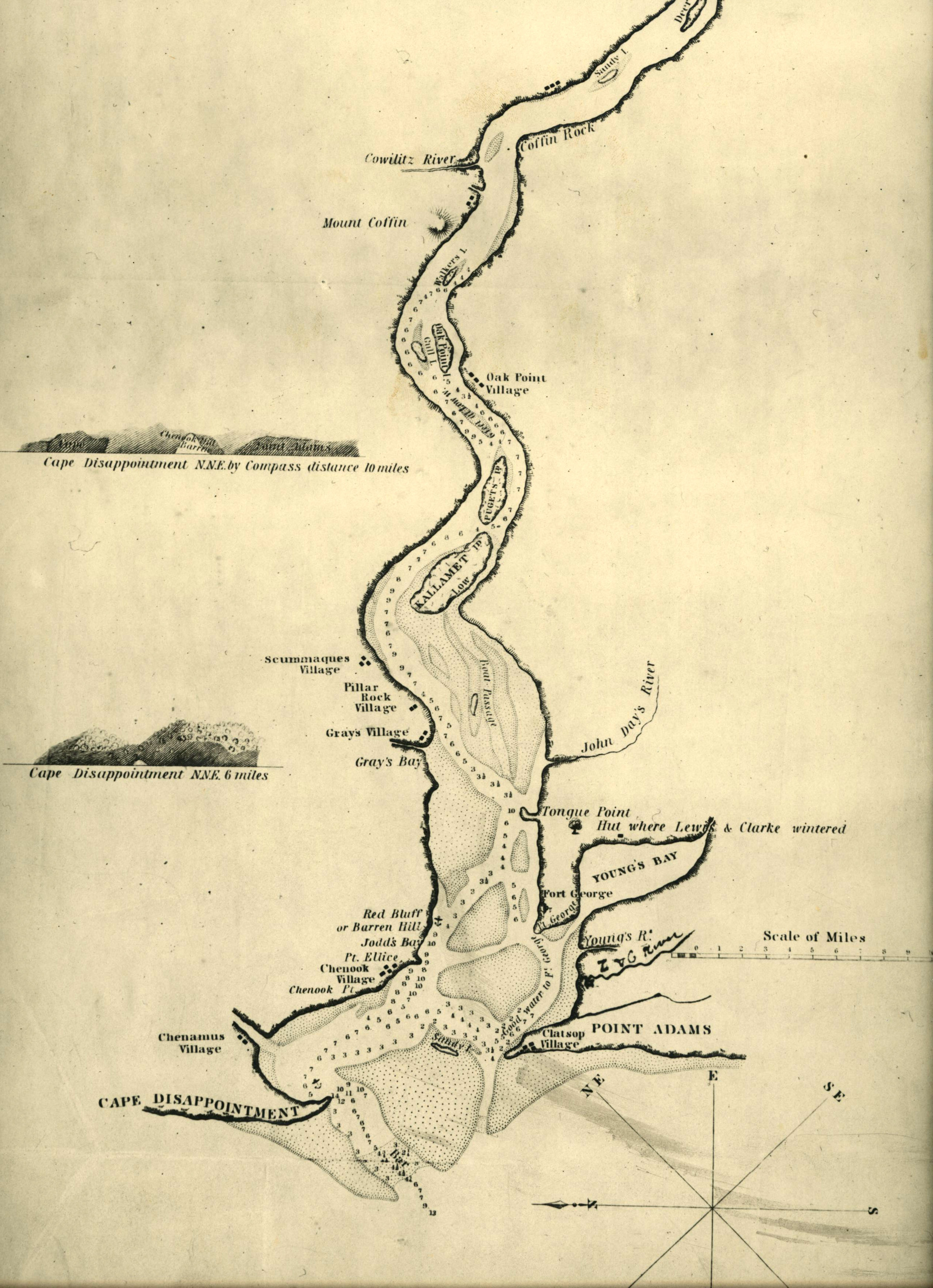

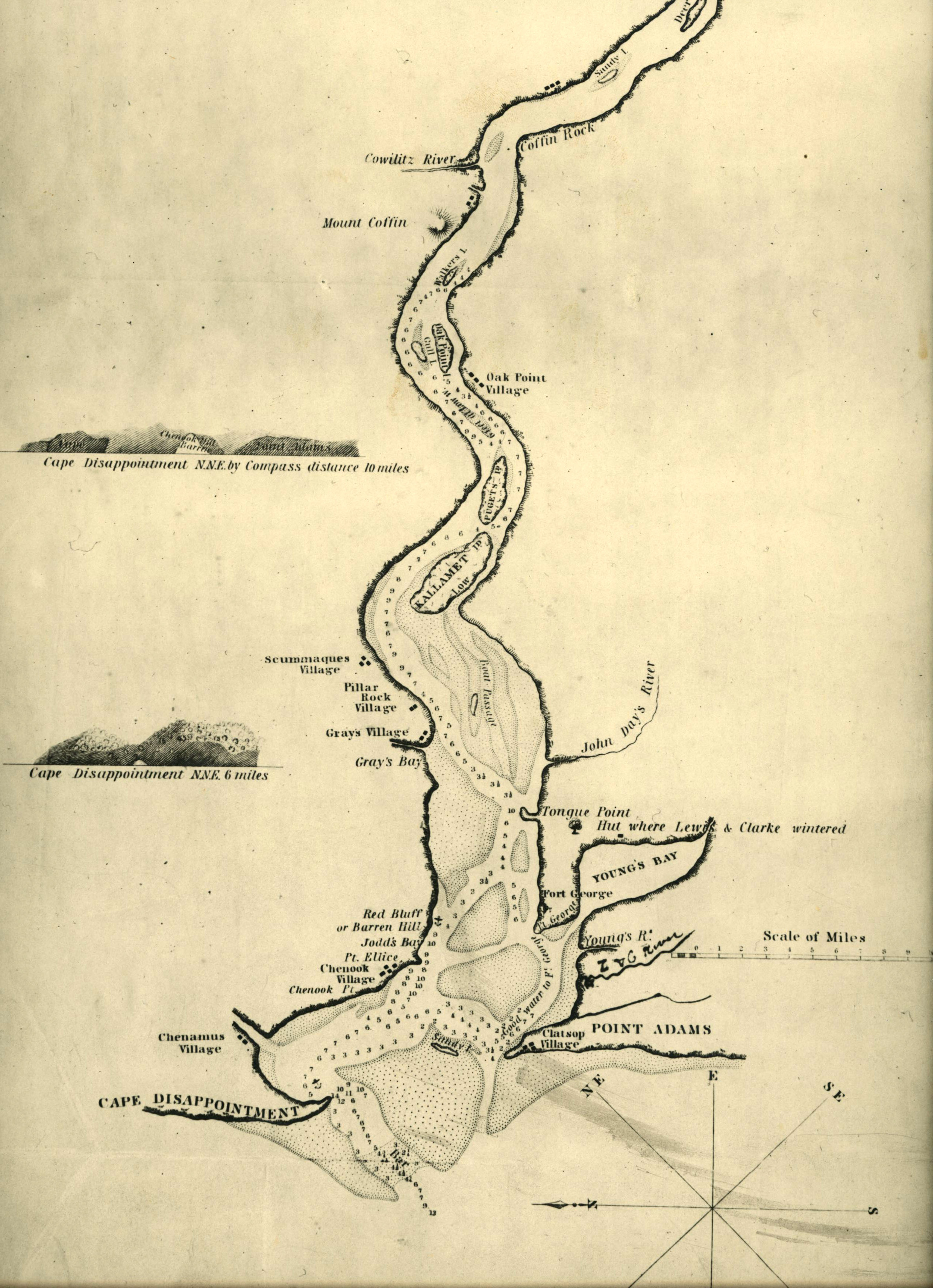

![Drawn from several surveys in the possession of W.A. Slacum ; by M.C. Ewing.]()

Chart of the mouth of the Columbia River for 90 miles from its mouth, 1838.

Drawn from several surveys in the possession of W.A. Slacum ; by M.C. Ewing. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., G4242.C62 1838 .E94

Related Entries

-

![Beeswax shipwreck]()

Beeswax shipwreck

Since the earliest days of EuroAmerican settlement on the Oregon Coast,…

-

![Point Adams]()

Point Adams

Located at the mouth of the Columbia River and marking the extreme nort…

-

![Santo Cristo de Burgos]()

Santo Cristo de Burgos

The Manila Galleon Trade and the Wreck on the Oregon Coast Nehalem-Til…

-

![Shipwrecks in Oregon]()

Shipwrecks in Oregon

Approximately three thousand ships have met their fate in Oregon waters…

-

![Silas Bryant Smith (1839-1902)]()

Silas Bryant Smith (1839-1902)

Silas Bryant Smith played a key role in recording the traditions, relig…

-

![U.S.S. Peacock]()

U.S.S. Peacock

The U.S.S. Peacock, a ten-gun, three-masted sloop, was the first ship o…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Barry, Neilson J. “Spaniards in Early Oregon.” The Washington Historical Quarterly 23.1 (January 1932): 25-34.

Cultee, Charles and Franz Boas. Chinook Texts. U.S. Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin No. 20. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, 1920.

Curtis, Edward Sheriff. The North American Indian. Volume 8, Appendix, p. 183. 1911.

Franchère, Gabriel. Narrative of a Voyage to the Northwest Coast of America in the Years 1811, 1812, 1813, and 1814. Translated and edited by J.V. Huntington. New York: Redfield, 1854.

Gibbs, George. Tribes of Western Washington and Northwestern Oregon, in Contributions to North American Ethnology, Volume I. Edited by John Wesley Powell. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1877.

Howard, Daniel Franklin. Oregon’s First White Men: A Complete Historical Novel. Rainier, Ore.: Rainier Review Press, 1927.

Howard, Daniel Franklin. Oregon’s First White Man. Poem (1924) and “Scenario of Dramatical Composition.” Both in manuscript papers of Daniel Franklin Howard held by the Stella Historical Society, Stella Washington.

Hult, Ruby. Lost Mines and Treasures of the Pacific Northwest. Portland, Ore.: Binfords and Mort, 1964.

Parrish, Philip H. “Before the Covered Wagon: Legends of Shipwrecked White Men.” Chapter III. The Sunday Oregonian, April 13, 1930.

Smith, Silas B. “Tales of Early Wrecks on the Oregon Coast, and How the Bees-wax Got There.” Oregon Native Son (January 1900).