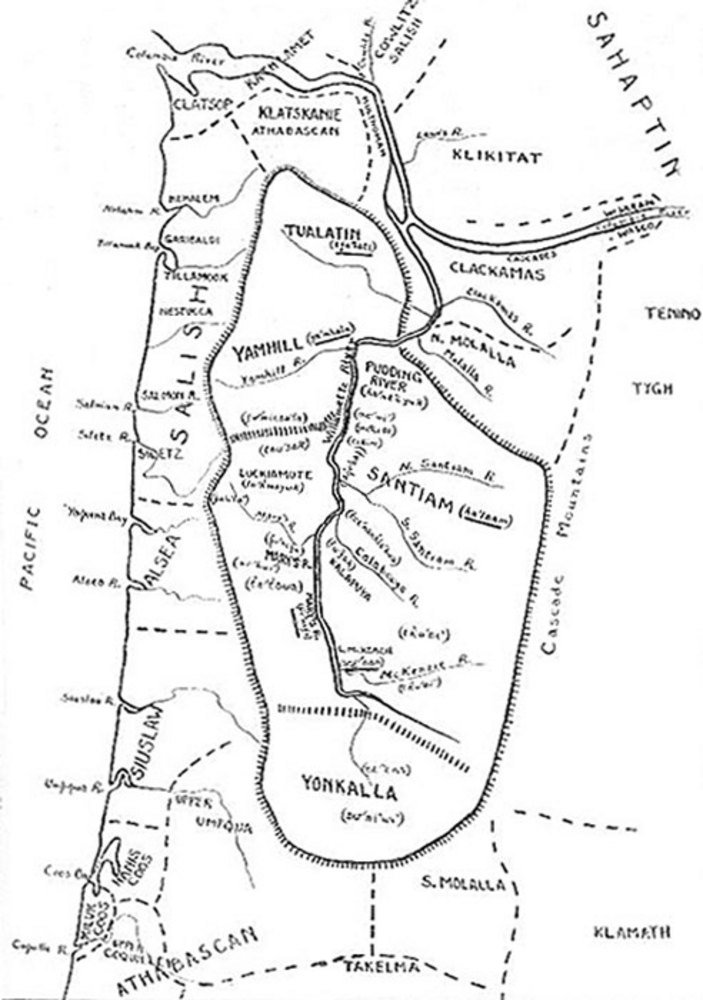

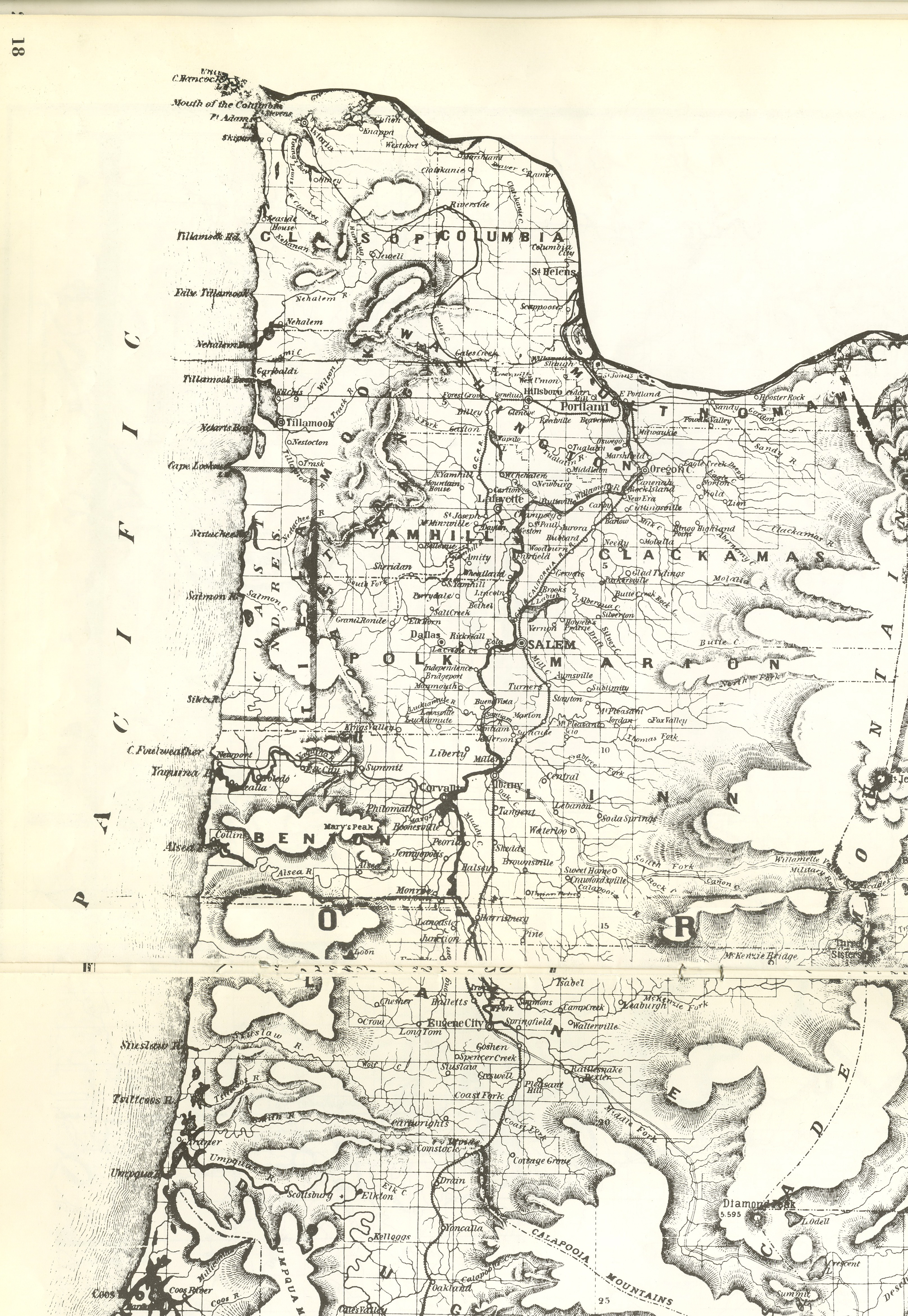

The name Kalapuya (kǎlə poo´ yu), also appearing in the modern geographic spellings Calapooia (for a river in Linn Country) and Calapooya (for a mountain range and creek in Douglas County), goes back to a term of uncertain origin and significance. It was applied by Chinookans of the lower Columbia River to speakers of the three Indigenous languages that are today termed Kalapuyan: Northern Kalapuya, spoken on the west side of the Willamette River from modern Washington County south to about Monmouth; Central Kalapuya, spoken on the east side of the Willamette River from Champoeg south to Salem and on both sides of Willamette River south at least to Eugene; and Southern Kalapuya, spoken on Elk Creek and perhaps also Calapooya Creek, both tributaries of Umpqua River.

Kalapuyans lived in tribal territories containing numbers of related and like-speaking, but basically autonomous villages. For example, sixteen named villages are known for the early nineteenth-century Tualatin Kalapuyans of modern Washington and Yamhill counties. Judging from treaty documents and the ethnographically better-described groups, tribal territories were associated with one or more tributary watersheds of the region’s two main streams—the Willamette River and the Umpqua River—with each territory offering a range of riverine, prairie, savanna, and forest habitats. Extensive prairies and savannas were a managed, not a natural, feature of this region, maintained by the Kalapuyans themselves, who burned off their grasslands at summer’s end.

Kalapuyans exploited a wide range of animal and vegetable resources specific to these different habitats, moving across their tribal territories in response to seasonal variations in resource availability. Vegetable resources, harvested primarily by women, were particularly important in their diet. These included especially the bulbs of the camas lily, available in remarkable seasonal abundance on the region’s low wet prairies. Curved hardwood digging-sticks, fitted at the top with transverse antler handles, were used to harvest the bulbs. Harvested bulbs were layered between leaves and buried in pit-ovens over fire-heated stones. Brown and sugary when done, they were then dried for storage; they might be further processed into small cakes, which were important articles of inter-group commerce.

Other important vegetable resources were wapato (Sagittaria latifolia), a marsh plant whose tubers were harvested during the fall, stored in pits, and baked in ashes for eating; tarweed seeds (Madia spp), beaten off standing plants on burned-over prairies, tossed with hot coals on bark or woven trays for parching, and finally ground into meal in stone mortars; and hazel-nuts, dried in the sun and beaten to remove their husks before being stored in soft-woven baskets. The acorns of the Oregon white oak were also used—shelled, then immersed in water or buried in wet clay to leach them, then ground into a meal which might be cooked with deer blood—but in contrast to many California Native peoples, Kalapuyans did not depend on acorns for their main subsistence.

The drier months found Kalapuyans camped out in the open, under minimal shelter. During the winter season of reduced harvest activity, they lived in winter houses at sheltered village sites. The division of the yearly cycle into clearly demarcated halves was reflected in personal attire, with warm-weather nudity noted for men only (women always had at least a skin or rush apron or short skirt) and robes and sewn buckskin clothing for cold weather (gowns for women, trousers and shirts for men, leggings and moccasins for both). Men favored fur caps, made from the intact skins of smaller animals or the head-skins of larger animals, while women wore tightly woven basketry caps.

The best documented of the Kalapuyan tribes is the Tualatin. Unlike Tualatins, interior Kalapuyans did not flatten the foreheads of freeborn infants, nor were they as active in the regional slave trade. At the same time, the practice of selling orphans and children of poor parents into slavery is noted only for interior Kalapuyans.

All the Kalapuyan groups suffered catastrophic population declines due to introduced diseases. The record on interior Kalapuyan groups is particularly fragmentary, with even the identification and original disposition of the tribes there in doubt. The first Indian census taken at Grand Ronde Reservation, to which all Kalapuyans were removed in 1856, shows eleven Kalapuyan “bands” there, with a total population of 344 men, women, and children.

-

![]()

Eliza Young (Kalapuyan), 1912.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, ORHI29505

-

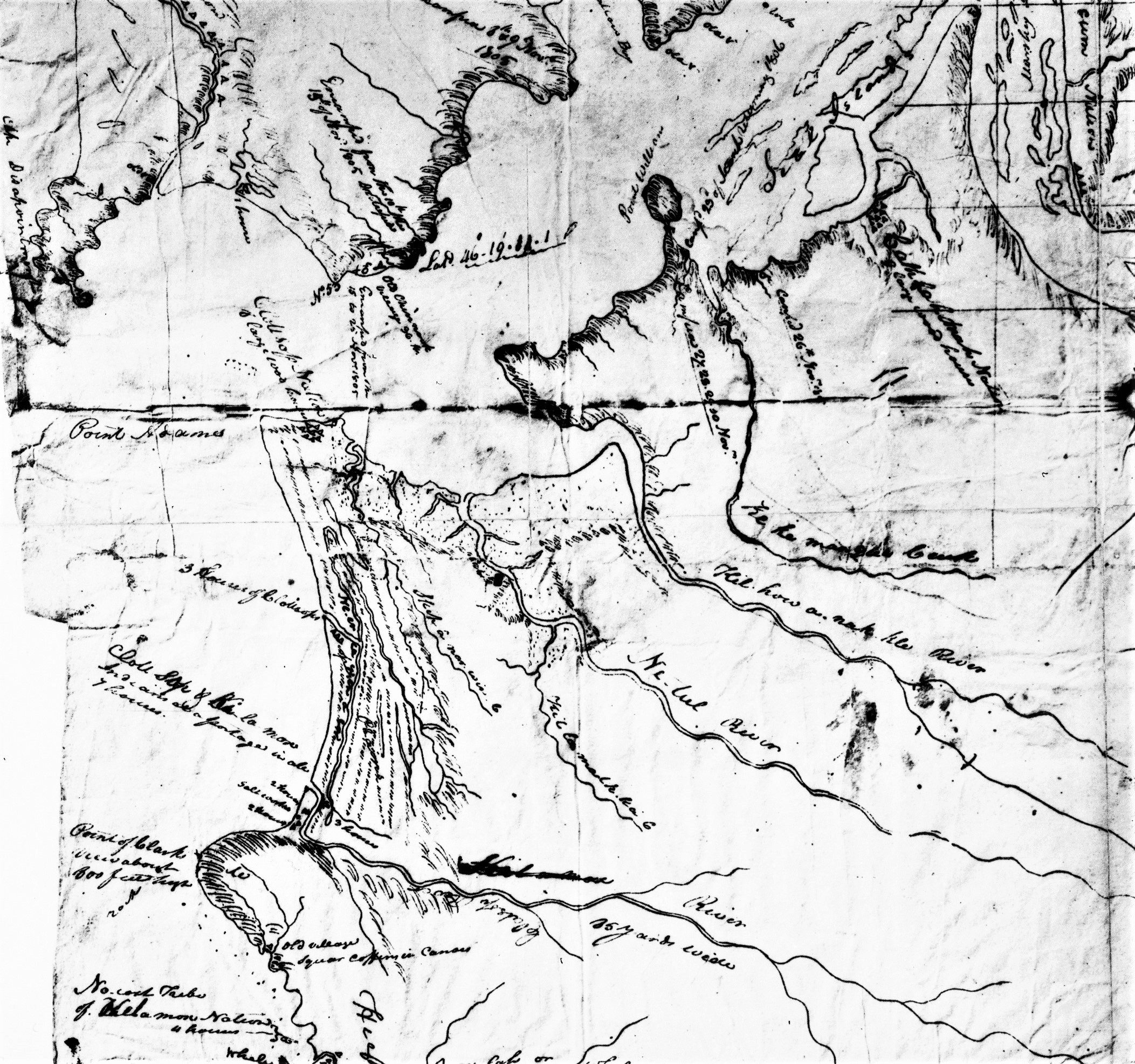

![Map of land purchases and reservations negotiated by Board of Commissioners]()

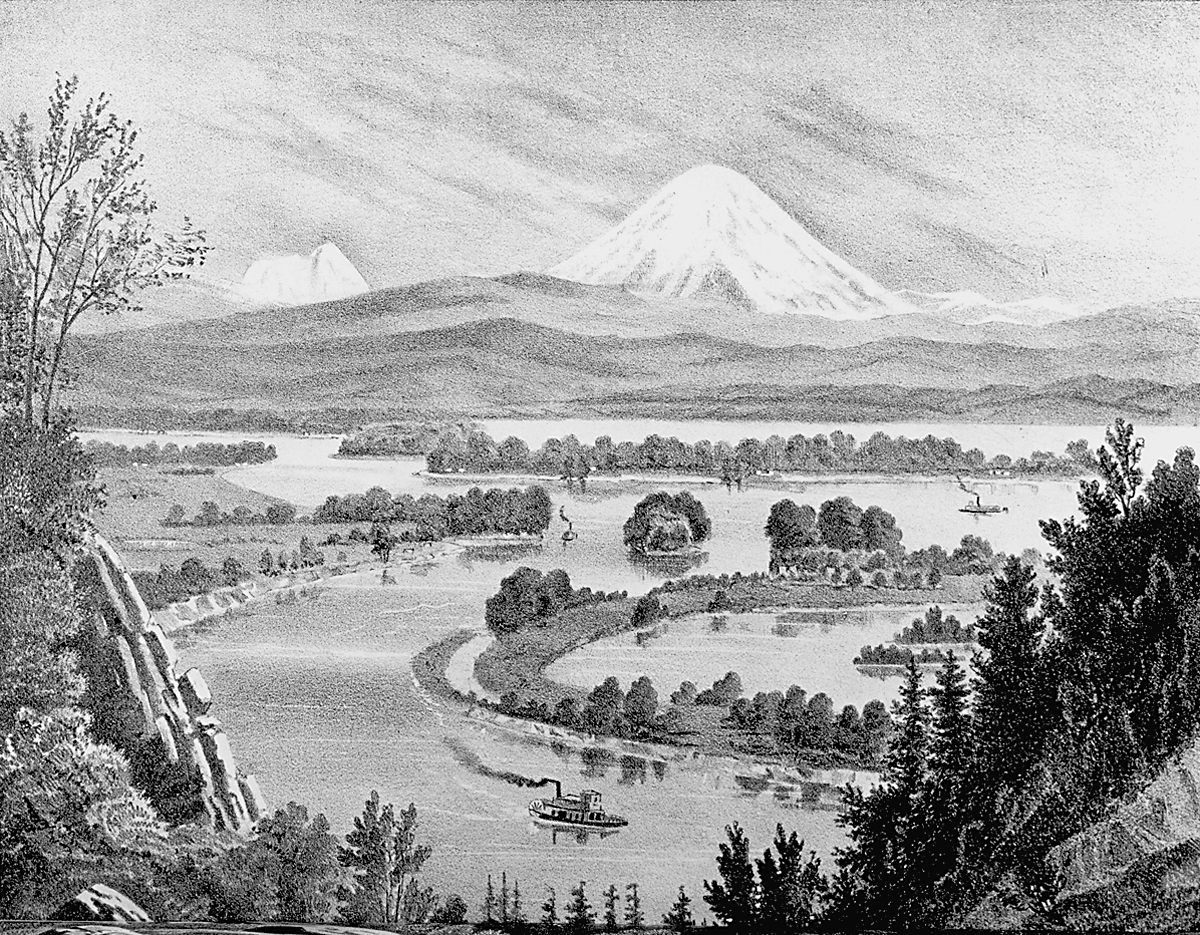

Sketch of the Wallamette Valley, George Gibbs and Edmund Starling, 1851.

Map of land purchases and reservations negotiated by Board of Commissioners Courtesy Oregon State University Special Collections and Archives Research Center, Corvallis -

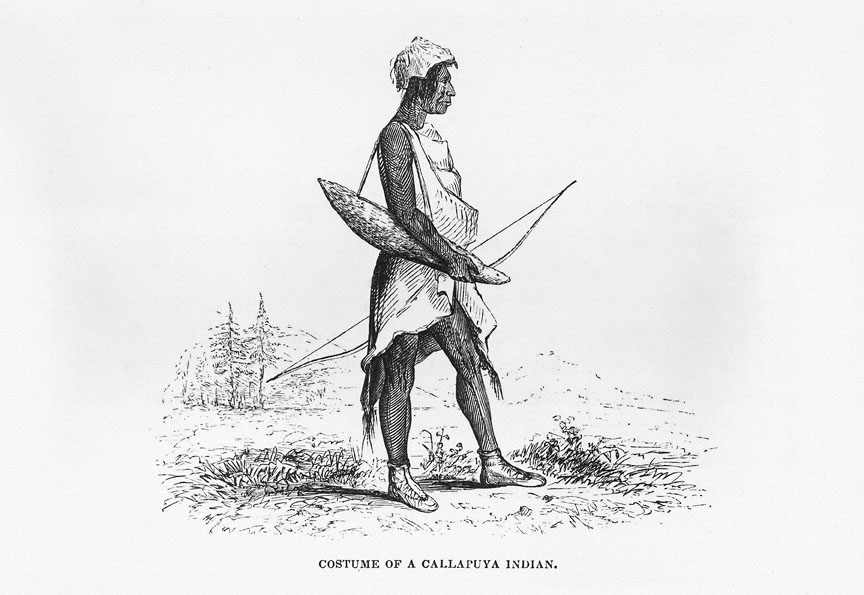

![]()

"Costume of a Callapuya Indian," 1841, by Alfred T. Agate.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 104921

-

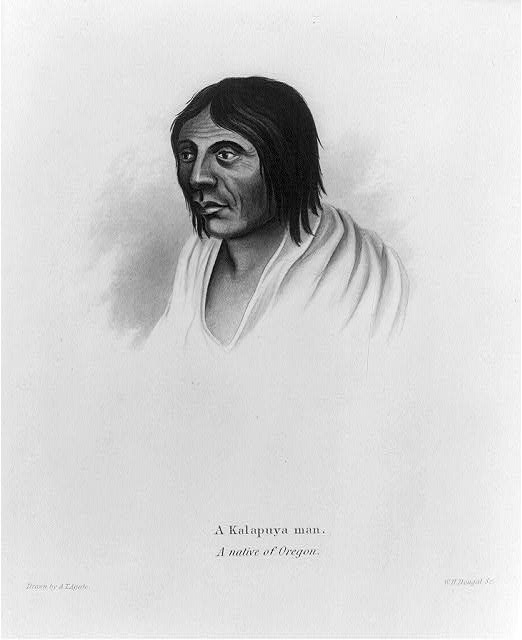

![Dougal, William H., Engraver, Alfred T Agate, and Charles Wilkes.]()

A Kalapuya man--a native of Oregon, 1844.

Dougal, William H., Engraver, Alfred T Agate, and Charles Wilkes. Courtesy Library of Congress,

Related Entries

-

![Camas]()

Camas

Camas is a North American bulb-forming geophyte whose greatest diversit…

-

![Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde]()

Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon is a confede…

-

![Disease Epidemics among Indians, 1770s-1850s]()

Disease Epidemics among Indians, 1770s-1850s

In 1972, historian Alfred Crosby introduced the term Columbian Exchange…

-

![Kalapuya Man Drawing]()

Kalapuya Man Drawing

Costume of a Callapuya Indian, also known as Kalapuya Man, is one of th…

-

![Kalapuya Treaty of 1855]()

Kalapuya Treaty of 1855

The treaty with the Confederated Bands of Kalapuya (1855) is the only r…

-

![Mill Creek Archaeological Sites (Salem)]()

Mill Creek Archaeological Sites (Salem)

The modern City of Salem occupies a former Kalapuyan townsite known as …

-

![Tualatin peoples]()

Tualatin peoples

Tualatin (properly pronounced 'twälə.tun in English) was the name of a …

-

![Western Oregon Klikatats (Klickitats)]()

Western Oregon Klikatats (Klickitats)

Between the 1810s and 1850s, a sizable segment of the Klikatat Tribe of…

-

Willamette River

The Willamette River and its extensive drainage basin lie in the greate…

-

![Willamette Valley]()

Willamette Valley

The Willamette Valley, bounded on the west by the Coast Range and on th…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Jacobs, Melville, ed. University of Washington Publications in Anthropology 11: Kalapuya Texts. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1945.

Mackey, Harold. The Kalapuyans: A Sourcebook on the Indians of the Willamette Valley (2nd ed.). Salem and Grand Ronde, Ore.: Mission Mill Museum Association and the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, 2004.

Zenk, Henry. "Kalapuyans." In Wayne Suttles, ed., Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 7: Northwest Coast, 547-553. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1990.