The U.S. Lighthouse Board completed Yaquina Head Lighthouse in 1873 on Yaquina Head, a narrow peninsula of Columbia basalt that juts nearly a mile out to sea, about three miles north of Newport. The headland is within the traditional territories of the Yaquina people and was an important place for harvesting shellfish and other coastal resources. In the mid-nineteenth century, the headland was close to the coastal midpoint of the Coast Reservation before it was reduced in size during the late 1850s and 1860s and then disbanded. The Yaquina Head Lighthouse rises 162 feet above the ocean beach. The 93-foot tower of the lighthouse is the tallest on the Oregon Coast, and the light can be seen nineteen miles out to sea.

The U.S. Lighthouse Board had long identified the Newport area as a location for a lighthouse to ensure that the coast had regularly spaced lights. Due to the board’s changing understanding about regional maritime commerce, however, the area ended up with two lighthouses. The board belatedly recognized that a lighthouse serving maritime traffic from Yaquina Head would assist mariners more than a local light that guided ships into Yaquina Bay.

There has long been confusion as to whether Yaquina Head Lighthouse was built on the correct headland. In early General Land Office records and survey plats, the headland was sometimes referred to as Cape Foulweather, but research confirms that the Lighthouse Board had always targeted Yaquina Head for the lighthouse. George Davidson’s Pacific Coast Pilot clarified the name in 1889, and beginning in 1896 the U.S. government’s List of Lights and Fog Signals, Pacific Coast of the United States referred to the headland as Yaquina Head.

Congress approved $90,000 (almost $2 million in 2020 dollars) for the Yaquina Head Lighthouse in 1871, but construction was slow and torturous. Workers wrestled with winter storms, and two boats were lost while trying to deliver building materials to the site. Construction materials shipped from San Francisco often had to be offloaded at Newport and then transported by wagon to the site. The double-walled tower required more than 370,000 bricks made by the Patent Brick Company in San Rafael, California, and metalwork was manufactured in Philadelphia and completed in June 1872 by Oregon Iron Works, a Clackamas company. The lighthouse tower was built using the same design as the Pigeon Point Lighthouse, constructed in 1852, fifty miles south of San Francisco. The keeper’s house, a two-and-a-half-story wooden structure, was completed in September 1872; a second keeper’s house was added in 1922.

A first-order Fresnel lens, built in France four years earlier by Barbier and Fenestre, was unpacked at Yaquina Head in October 1872. Transshipped from New York, it arrived on the Oregon Coast after having been portaged across the Isthmus of Panama. While preparing for the first lighting in early 1873, it was discovered that crates containing pieces of the lantern had been lost at sea, and the lighthouse startup was delayed while a replacement was manufactured and shipped to Oregon. Finally, on August 20, 1873, Fayette Crosby, the first keeper, lit the four-wick, lard-oil Yaquina Head Lighthouse lantern, which shone with a fixed white-light pattern. As fog was uncommon at Yaquina Head, the lighthouse had no fog signal.

The U.S. Lighthouse Service assigned a head keeper and two assistants to run the lighthouse. The keepers and their families relied on supplies delivered by the lighthouse tender, but they also grew vegetables, pastured cows, and raised hens. Wind and rain battered the tower relentlessly, and a high fence was built in 1880 to shield the buildings and windows from windblown rocks torn from the cliff.

The lantern switched to mineral oil in 1888, and the lighthouse was electrified in the early 1930s, changing its light from fixed to flashing. The lighthouse logged nearly 10,000 visitors in 1924, and by 1938 Yaquina Head was the most visited lighthouse on the West Coast and the fourth most visited in the country. The original keeper’s house was torn down in 1938 and replaced. The U.S. Coast Guard became the light’s manager in 1939, and the service stationed seventeen servicemen at Yaquina Head during World War II to keep a lookout for enemy ships and submarines. Both keeper dwellings were demolished in 1984, having been abandoned since the last Coast Guard keepers left in 1966, when the light was automated.

Congress designated a hundred-acre Outstanding Natural Area on Yaquina Head in 1980, managed by the Bureau of Land Management. The Coast Guard handed the station over to the BLM in 1993, and it was opened to the public. The Coast Guard still operates the automated lighthouse lantern, and the BLM opened the Yaquina Head Interpretive Center in 1997. In 2005, BLM spent more than a million dollars to restore the tower and the light apparatus, which included replacing cast iron pieces on the tower with authentic iron and bronze castings.

Yaquina Head Lighthouse has some 400,000 visitors a year. The BLM’s nearby Yaquina Head Interpretive Center features exhibits on local seabirds, marine and intertidal life, the keepers' lives and duties at the lighthouse, and a full-scale replica of the lighthouse lantern.

-

![]()

Yaquina Head Lighthouse.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 581, 989mo11

-

![]()

Yaquina Head Lighthouse.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org. Lot 581

-

![]()

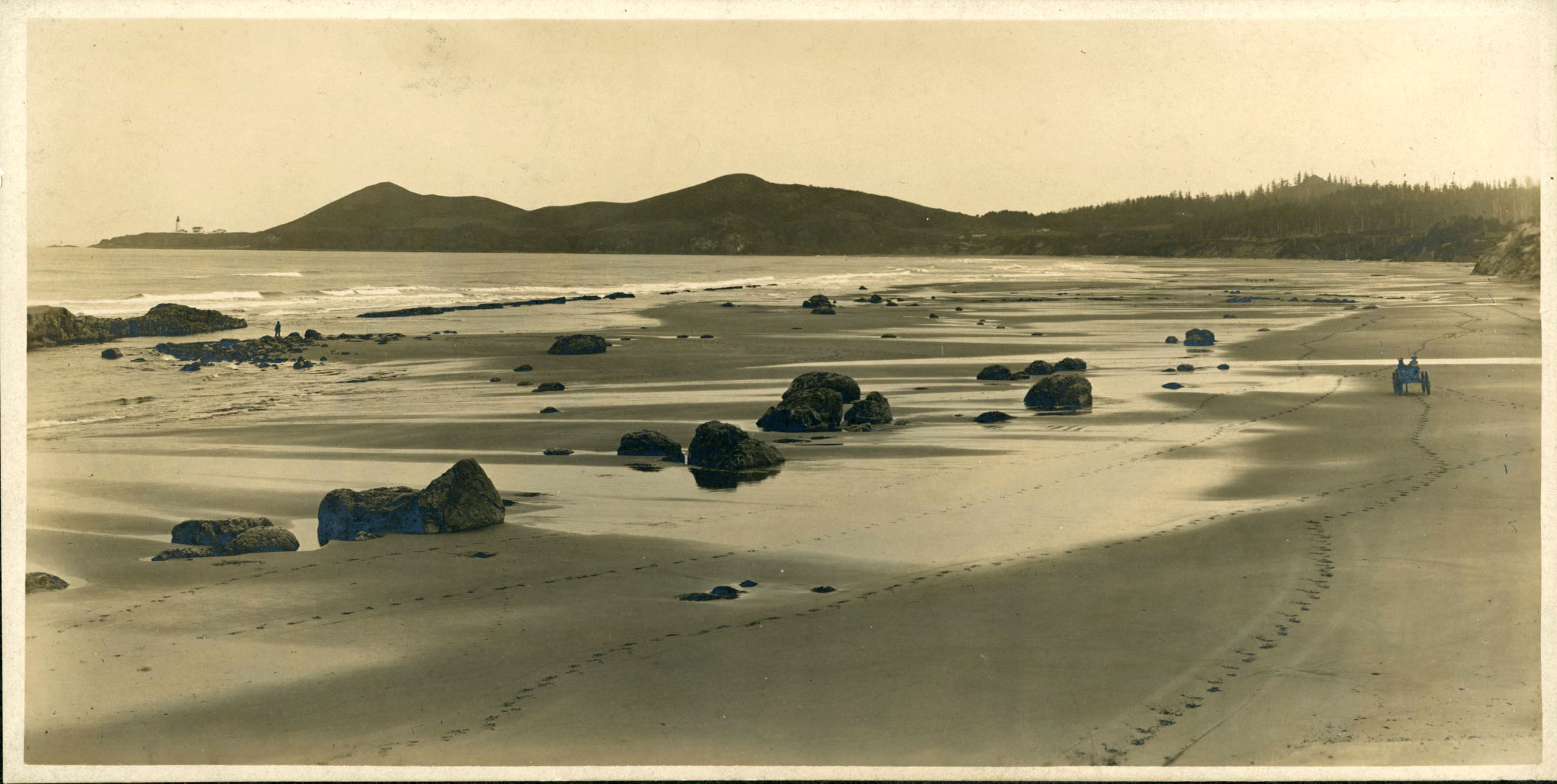

Nye Beach with Yaquina Head Lighthouse in the distance, 1902.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., ba013826, photo file 800a

-

![]()

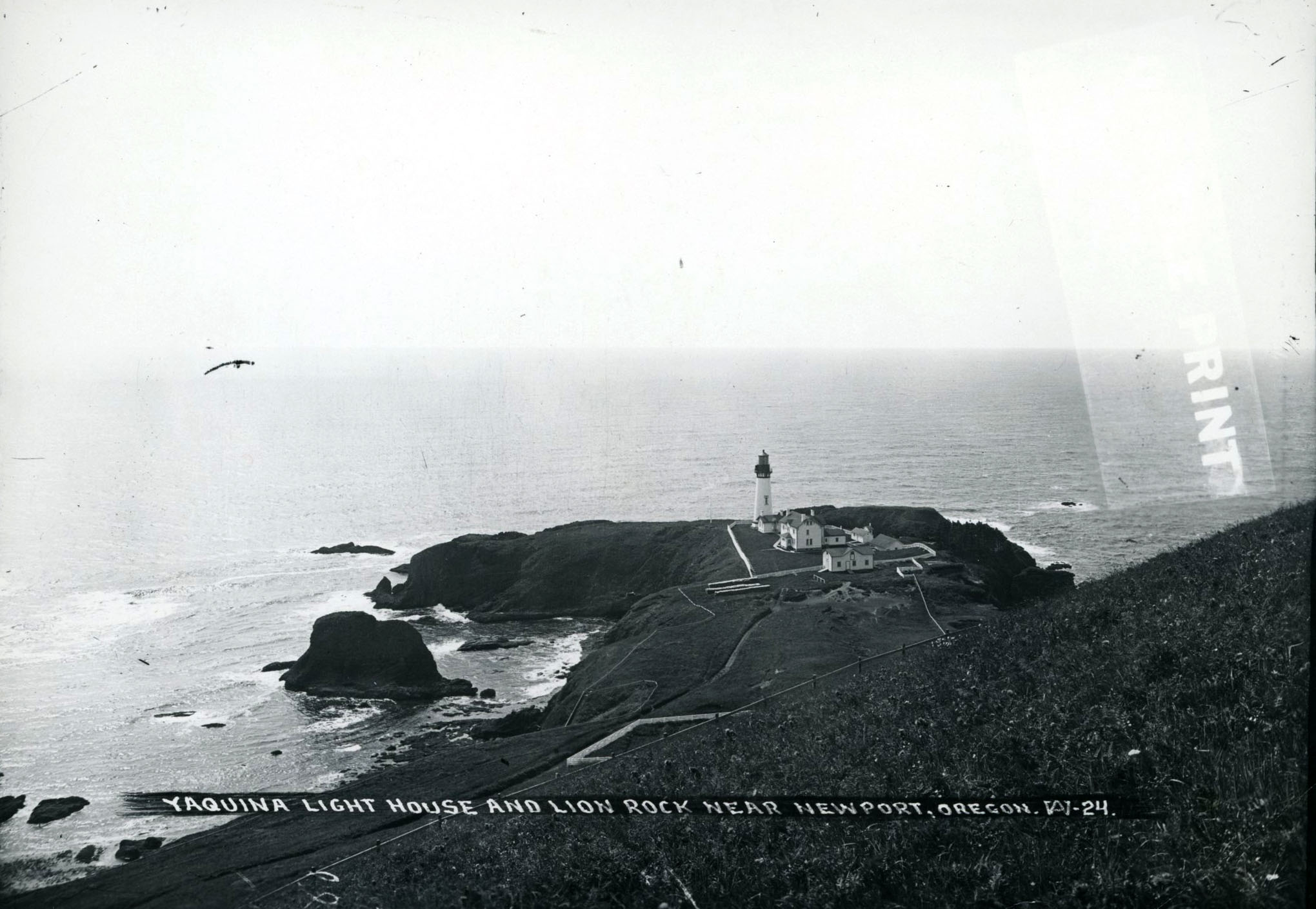

Yaquina Head Lighthouse and complex.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., ba013806, photo file 800a

-

![]()

Yaquina Head Lighthouse.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., ba013707, photo file #800a

Related Entries

-

Coast Indian Reservation

Beginning in 1853, Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer negotia…

-

![Newport]()

Newport

Newport, with a population of about 10,256, is the largest city in Linc…

-

![U.S. Bureau of Land Management]()

U.S. Bureau of Land Management

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) administers over 15.7 million acres…

-

![U.S. Life-Saving Service in Oregon]()

U.S. Life-Saving Service in Oregon

The mission of the U.S. Life-Saving Service was to rescue those in peri…

-

![Yaquina Bay Lighthouse]()

Yaquina Bay Lighthouse

Yaquina Bay Lighthouse, built in 1871, is currently the only wooden lig…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Gibbs, James, and Bert Webber. Oregon’s Seacoast Lighthouses. Medford, OR: Webb Research Group, 1992.

"Yaquina Head Lighthouse." Friends of Yaquina Lighthouses. http://lighthousefriends.com/light.asp?ID=133.

Nelson, Sharlene, and Ted Nelson. Umbrella Guide to Oregon Lighthouses. San Luis Obispo, CA: EZ Nature Books, 2007.

Annual Report of the Secretary of the Treasury on the State of the Finances for the Year 1872. Report of the United States Lighthouse Board, 1872. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1872.