On a fence post in Wheeler County, a sandy brown bird delivers a rich song, beginning with loud, clear, flute-like notes followed by a jumble of sweet notes. The stocky, robin-sized bird turns, revealing the yellow breast marked with a bold black “V” identifying it as a western meadowlark (Sturnella neglecta). It is the distinctive song heard throughout farm country that led to the western meadowlark's adoption as Oregon’s state bird in 1927.

Western meadowlarks can be found wherever native grasslands are thick, from the Owyhee River country of Malheur County to the bunchgrass hillsides outside The Dalles to the mounded prairies of Jackson County. They are most abundant in the bunchgrass prairies surrounding the Blue Mountains and in the Rogue Valley. A few nest along the southern Oregon coast. Their song can still be heard in scattered places in the Willamette Valley, but the once-common prairies have largely been replaced by closely tended fields and pastures unsuitable to nesting meadowlarks. Most of the remaining birds are in the southern portion of the valley.

Although it looks more like a sparrow, the meadowlark is closely related to blackbirds, cowbirds, and orioles. Male and female are similar in appearance, though the male is brighter in color. Like many grassland birds, meadowlarks are polygamous: two-thirds or more of the males in a given population have two mates, while a few have three.

Grasslands harbor many predators, but there are few opportunities to hide a nest, so meadowlarks construct a domed nest concealing it from above. Some females build a grass-covered tunnel leading to their nests. When disturbed, the female runs off some distance before flushing, giving little clue to the location of her nest.

Meadowlarks typically rear two broods a year, averaging five eggs per clutch. The white eggs, heavily speckled with brown, hatch in thirteen to fourteen days, and the young fledge in ten to twelve days.

Western meadowlarks forage on the ground using their long beak to probe deep into grass tussocks. By spreading their beaks, they separate the stems to expose grubs, seeds, and food items not visible to other birds. Typically, one bird stands guard watching for hawks or other threats, while the mate or other members of a flock forage.

In winter, flocks of fifty or more birds may be encountered west of the Cascades. Many of them originate from the north and east, possibly from as far away as British Columbia. A few remain east of the Cascades with the coming of colder weather, most at lower elevations. The first returning birds are seen in February, and territorial males are well established by early April.

Most bird species undergo a complete molt in late summer, replacing all their feathers. Many initiate a second, partial molt prior to the breeding season when they don bright breeding colors. Meadowlarks forego a partial molt. Instead, brighter breeding colors are revealed by the wearing away of the dull tips of the feathers acquired the previous summer.

-

![]()

Watercolor painting by R. Bruce Horsfall depicting a Western Meadowlark and a Streaked Horn Lark, 1921.

Oregon Historical Society Museum Collection, 2019-27.36.1,.2.

-

![]()

Western Meadowlark.

Courtesy Oregon Dept. of Fish and Wildlife

Related Entries

-

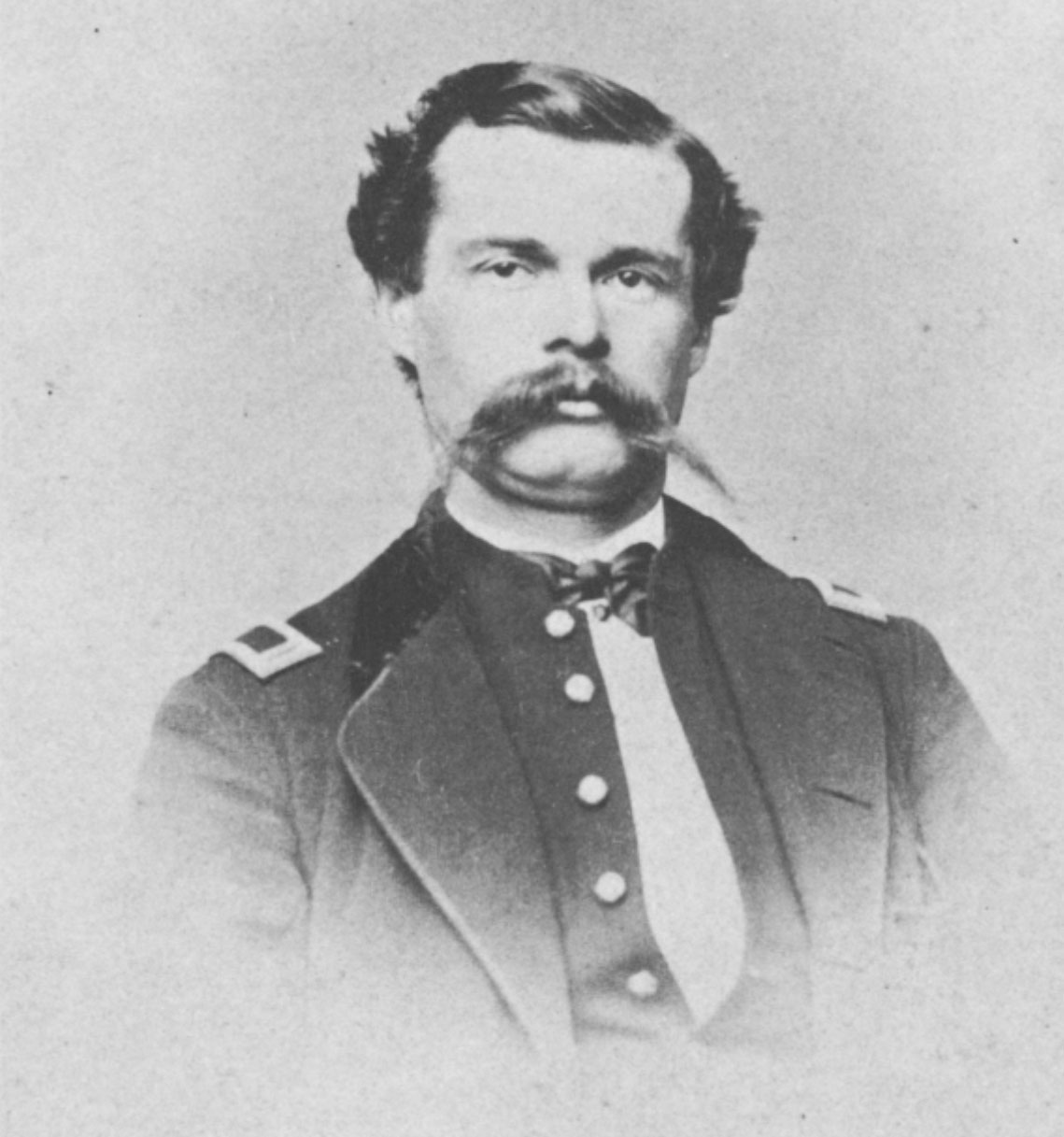

![Charles Bendire (1836–1897)]()

Charles Bendire (1836–1897)

Charles Bendire was a U.S. Army officer and naturalist who brought the …

-

![Marbled Murrelet]()

Marbled Murrelet

The marbled murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus) is a unique and cryptic…

-

![Northern Spotted Owl]()

Northern Spotted Owl

Natural History The northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina),…

-

![Oregon Junco]()

Oregon Junco

A hundred years ago, many birds carried the name of “Oregon,” including…

-

![Oregon State symbols]()

Oregon State symbols

Oregon has a number of officially designated symbols, ranging from thos…

-

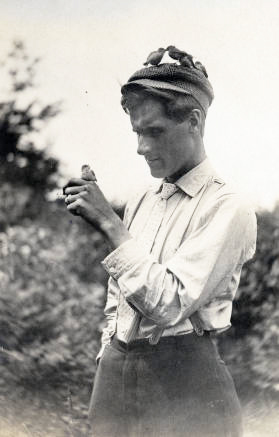

![William L. Finley (1876–1953)]()

William L. Finley (1876–1953)

Oregon's birds have had few better friends than William Lovell Finley. …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Altman, B. "Western Meadowlark Sturnella neglecta." In Birds of Oregon: a General Reference, edited by D.B. Marshall, M.G. Hunter, and A.L. Contreras, 580-582. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2003.

Gabrielson, I.N. and S.G. Jewett. Birds of the Pacific Northwest. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1970.

Horn, A.G., T.E. Dickenson, and J.B. Falls. "Male quality and song repertoires in Western Meadowlarks." Canadian Journal of Zoology 71 (1993): 1059-1061.